Book Notes: The Age of Inflation, by Jacques Rueff

October 14, 2012

A friend suggested that I should read some books by Jacques Rueff, an economist of some influence during the 1930s to 1960s. I looked into Rueff in the past and didn’t see anything that warranted more investigation. However, it is hard to be too critical of someone when you have admittedly not read what he had to say, so the time has come to look into Rueff’s work in more depth.

This book, The Age of Inflation, is a series of essays from 1932 to 1961. You can download it here:

http://www.scribd.com/doc/96554552/The-Age-of-Inflation-Jacques-Rueff

I think I will just let Rueff have his say, and include some comments in RED here and there. This essay is the last in the book. It was apparently done in 1961.

6. THE MONEY PROBLEM OF THE WEST

The West is for us the land of freedom. The Strasbourg lore has it that the Kehl Bridge, during the French Revolution, displayed a huge sign which read: The French Republic, One and Indivisible— Here Begins the Land of Freedom. The land of freedom is the land where men freely choose what they want to do, where they want to live, and how they want to use their means—where, in other words, they decide what contribution they want to make to the supply and demand of the market place, and thereby to the supply and demand of the country as a whole

It requires no great imagination to realize that if the manifold currents of supply and demand in each section of the market place were not co-ordinated, and if the over-all demand was apt at any time to get seriously out of line with the over-all supply, the land of freedom would also be the land of disorder. But it does not have to be so. The liberal economic order is no less precise and no less strict the planned order. For long periods of time, and despite the freedom of individuals to make their own choices, prices remained stable, markets were well adjusted, and from country to country the balance of payments was as it should be—in balance.

NWE: And so, after a brief opening of general libertarian sentiments, we soon get to Rueff’s overriding concern: the “Balance of Payments.” Whenever anyone starts talking about the “Balance of Payments,” a red flag goes up for me, because the “Balance of Payments” is something that is virtually never a problem in itself. The “Balance of Payments” is always in balance. This is a tautology of trade: trade is the exchange of one thing for another thing. This “thing” might be a financial commitment, like a bond, but nobody “trades” something for nothing. That’s a gift.

April 4, 2012: The Gold Standard and “Balanced Trade”

September 8, 2011: Gold and the Trade Deficit

The “Balance of Payments” doesn’t require any government oversight or adjustment to make it balance.

However, there are a great many different sorts of problems which may have an effect on the “Balance of Payments.” For example, if a government is running a large budget deficit, this might turn up as a “current account deficit” as the available domestic savings of the economy is not capable of meeting this demand for capital. A large budget deficit might indeed be a bad thing, but it is not really a “balance of payments” problem, it is a fiscal policy problem. The better economists will just focus directly on the real problem — in this case, fiscal policy — and not bother nattering about the “balance of payments imbalance.”

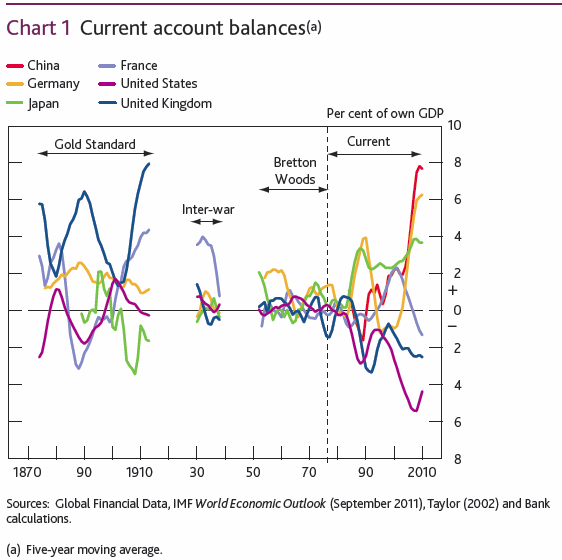

What Rueff apparently means when he says that the balance of payments was “in balance” is that there was not a “current account deficit” or a “current account surplus” under a gold standard system. This is completely false.

Here is a longer term look at the “balance of payments” for the United States, from 1821 to 1900:

March 4, 2012: U.S. Current Accounts and Bullion Flows, 1821-1900

I shall deal here in particular with the achievement of equilibrium in the balance of payments. The number and diversity of the individual decisions that combine to give form to a balance of payments make it easy to realize how great the odds are against achieving any real equilibrium. If these decisions are free, in the way that they have been free in our country since import quotas were abolished, equilibrium cannot be the result of chance. It can exist only if there is an appropriate mechanism to bring about. This mechanism can take various forms, according to whether the monetary system is based on inconvertible money with fluctuating rates of exchange or on convertible money with stable exchange rates.

NWE: As we can see, there was no “achievement of equilibrium in the balance of payments” so we are just talking about a fantasy world in Rueff’s imagination, not the real world. This is about the point at which I would normally get a little tired of reading Jacques Rueff.

A system of the latter type was that of the metallic currencies, as these existed before the last war— that is, currencies freely convertible into gold bullion at fixed rates. Under that system, the balance of payments was kept in proper shape as a direct result of the transfers in purchasing power that were brought on by any imbalance in a country’s obligations towards other countries. When the balance was unfavourable, the gold or foreign exchange that had to be purchased to make up the deficit caused the purchasing power in the debtor country to contract by a corresponding amount. The over-all purchasing power, represented by the aggregate income, in that country consequently became less than the total value of its output. This, in turn, released for export sufficient wealth to restore the equilibrium of the balance of payments, and in due course stimulated price movements which made such wealth attractive to foreign buyers.

Of course, this process was more complicated than the foregoing brief analysis seems to imply. But regardless of how complicated it was, its driving force was the mechanism I have just described.

This system operated efficiently for an entire century, up to the very eve of the First World War. It caused prices to remain remarkably stable, despite a major expansion in production; it provided a means of keeping foreign obligations in balance; and, as a consequence of all this, it was the keystone of monetary stability in all the countries that submitted to its discipline.

After the war, the countries of the West were so convinced that the gold standard was indispensable to their economic stability that they decided to reinstate it without delay, regardless of the difficulties involved. In 1920, however, the gold price index was 246, against 110 in 1913. The volume of money in circulation had increased to the same extent. Because, whether for reasons of fact or in law, the amount of gold reserves needed to maintain convertability is in direct proportion to the amount of money in circulation, which is backed up by these reserves, it was evident that not enough gold would be available for purposes of convertibility unless the price of gold was changed.

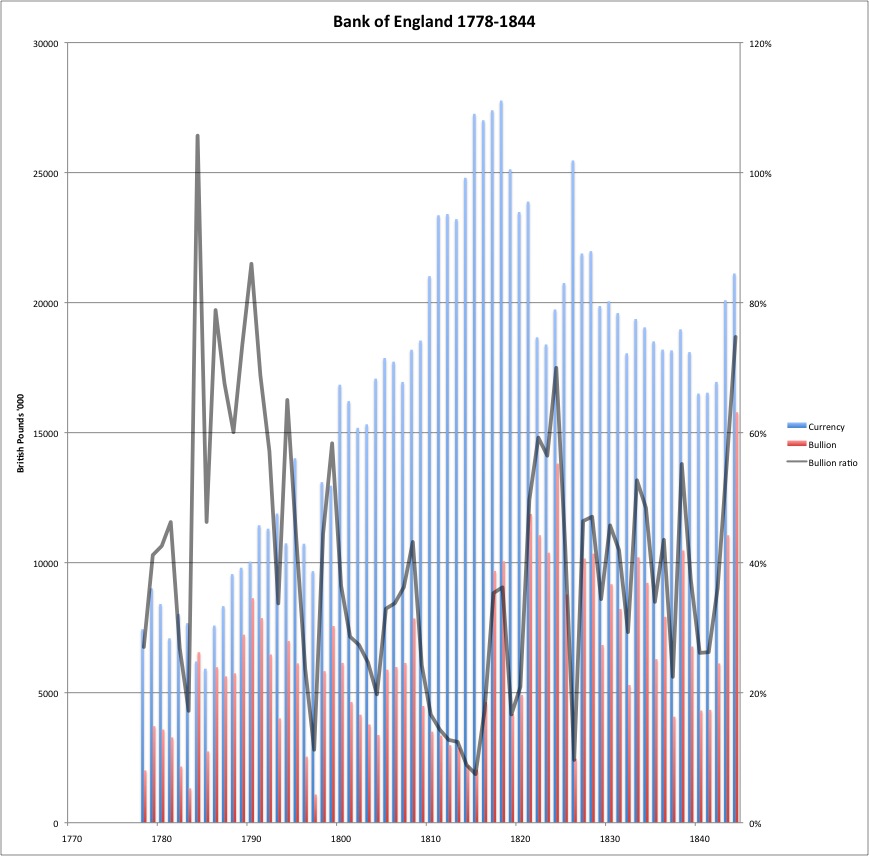

NWE: Rueff is talking about the fact that many currencies were devalued during World War I. During the early 1920s, several countries raised the value of their currencies back to their prewar parity values with gold, with Britain leading the way here. The “volume of money in circulation” did not increase to the same extent, however. This is again evidence that Rueff has a rather poor grasp of how monetary systems actually operate. The amount of gold reserves “needed to maintain convertibility” is never in “direct proportion to the amount of money in circulation.” We saw earlier that the gold bullion reserves of central banks, and aggregate commercial banks in the U.S. case, actually varied rather dramatically, with no particular ill effects.

January 23, 2011: The Gold Standard in Britain 1778-1844

January 30, 2011: Italy With the Gold Standard 1861-1914

January 9, 2011: The “Money Supply” With a Gold Standard 2: 1880-1970

January 2, 2011: The “Money Supply” With a Gold Standard

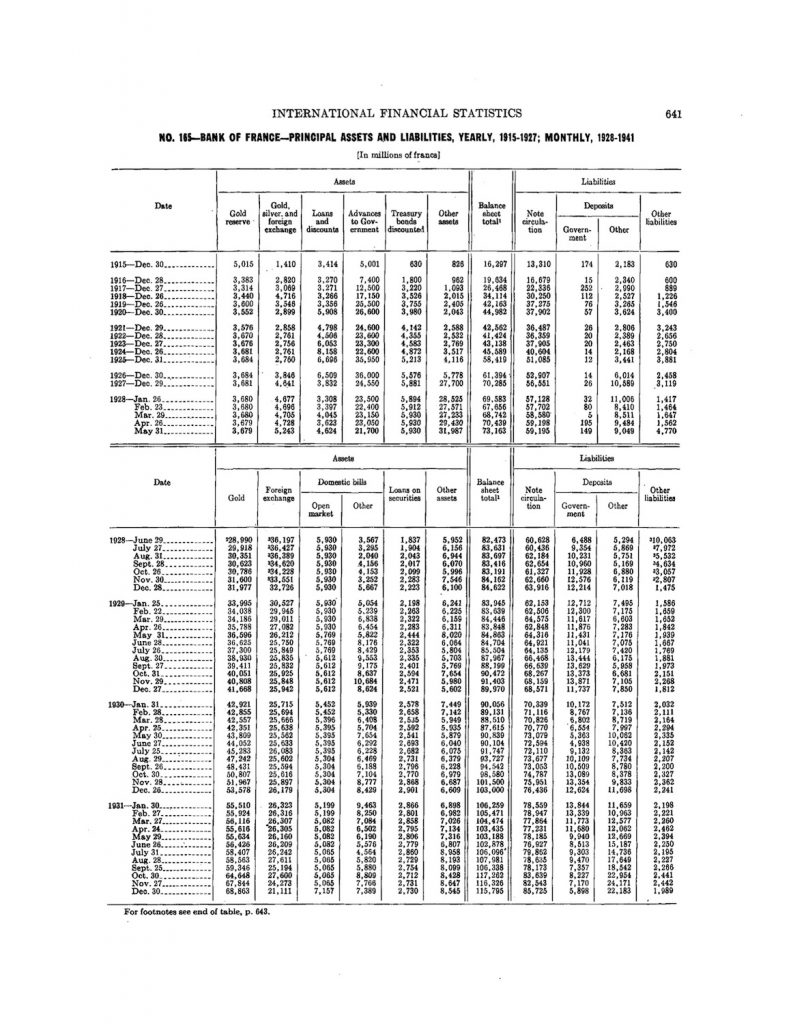

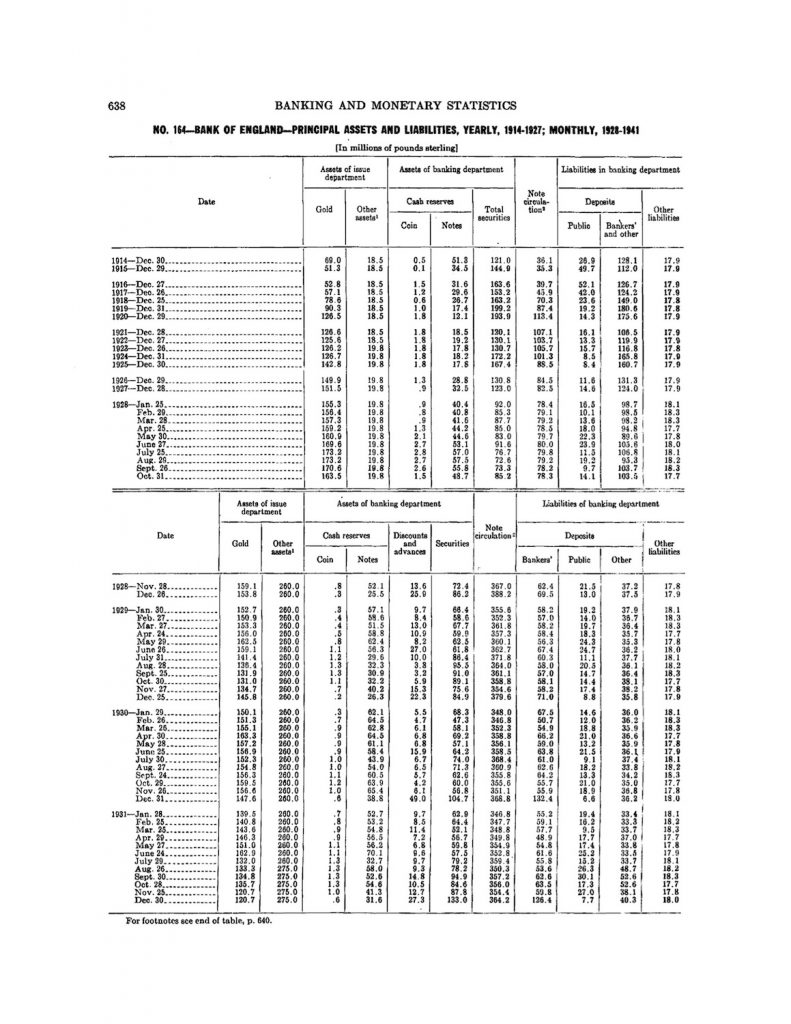

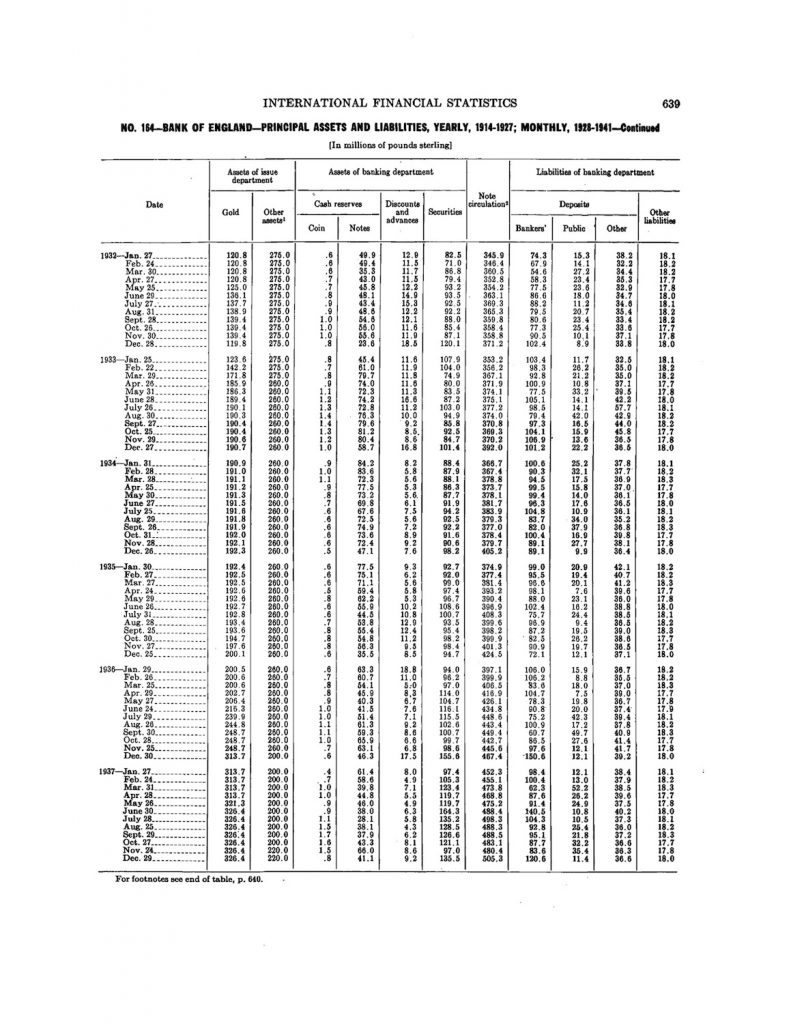

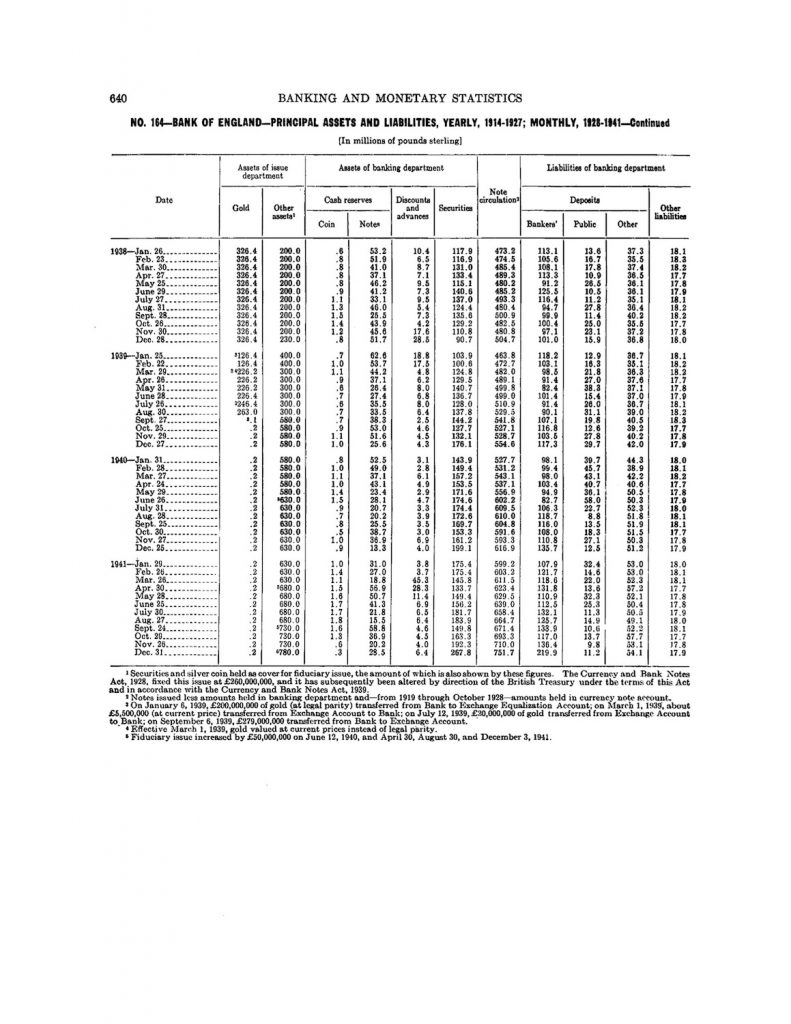

If you want to see the Bank of England’s balance sheet from 1914-1941, look here:

http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/docs/publications/bms/1914-1941/section15.pdf

Now, because I know you are all lazy as heck, I will put the relevant part here:

It was for this reason that the monetary conference which met at Genoa in 1922 recommended in resolution 9 the conclusion of an international convention; that would “embody some means of economizing the use of gold by maintaining reserves in the form of foreign balances.” As a result of this recommendation, the system designated merely as the “gold-exchange standard” replaced the old gold standard after the First World War in France and Germany, and all the other countries whose currencies had been restored by the Financial Committee of the League of Nations. lt collapsed during the Depression, but rose again from its ashes after the Second World War.

According to the principles of this system, a central bank is authorized to create money not only against instruments of indebtedness in domestic currency or against gold, but also against other currencies payable in gold (after the First World War against pounds sterling and dollars, and after the Second World War mainly against dollars. [footnote: Within the sterling zone, the pound sterling was governed by a special regime similar to that of the dollar.] Hence when, as a result of the balance-of-payments deficits of the United States, the central banks of the Western countries—especially the Bundesbank, the Bank of Italy, the Bank of Japan and, although to a lesser extent, the Bank of France —came into the possession of dollars or claims payable in dollars, they did not demand the gold to which their dollars entitled them, but instead left some or all of these dollars on deposit in the United States, where they were generally lent out to American borrowers. The central banks looked upon this new system with particular favor because it enabled them to substitute income-producing assets for entirely non-productive gold bullion and specie.

NWE: The “gold exchange standard” is basically just a currency board. There’s nothing particularly mysterious about it. For the most part, it appears that the banks responsible for the currency board operation followed the correct principles of operation. A currency board maintains one currency at a fixed parity with another currency, for example the British pound. We use them today, for this purpose, and they work well. This was actually in common use pre-1914 as well — by India and Japan, and I think the Philippines among others — although not so common as after 1920.

The international monetary system thus came to resemble a group of children playing marbles who agree that after each game the losers will get back the marbles they have put up. To the extent that the central bank of the creditor country gives back to the debtor country, in the form of a loan, the foreign exchange that it has received in the settlement of its debts, the debtor country can rest assured that, for the duration of the loan, the balanceof- payments deficit will not entail any international settlements. The monetary consequences of the deficit will simply be wiped out.

A great revolution has accordingly been wrought by the gold-exchange standard, and the result has been to give to those countries whose currencies have international prestige the marvellous secret of a “deficit without tears,” whereby they can give without receiving, lend without borrowing, and buy without paying. The discovery of this secret has also had a profound psychological effect on the people benefiting from a boomerang currency, for the domestic consequences which under the gold standard would result from a balance-of-payments deficit have been lessened or eliminated.

The gold-exchange standard has thus brought about conditions which are favourable to the great change in international traditions that has been initiated by the generous policy of giving. By leaving to the giver the joy of giving and to the recipient the joy of receiving, it has had only one result—the monetary situation which was described by President Kennedy in one of his first messages. The effects of this situation must now be examined.

NWE: Rueff doesn’t seem to understand the principles of currency board operation. It’s actually pretty simple. The currency board operator agrees to trade, let’s say, five French francs for each British pound. Thus, there is a 5:1 exchange rate. It is what I have called a “making change” system. You could call it a “warehouse receipt” or a “100% reserve” system if you wanted to.

July 28, 2011: Making Change: The Simplest Practical Gold Standard System

Each time someone brings a British pound to the currency manager, and receives five francs in trade, the manager’s “reserve holdings” of British pounds (actually British pound bonds, because the pounds received are immediately used to buy bonds) increase by one pound, and the amount of franc base money in existence increases by five francs. Thus, for each five francs of base money in existence, there should be one British pound held in reserve. If someone comes to the currency manager and wants to trade five francs for one British pound, then the currency manager’s reserve holdings shrink by one pound and the franc base money supply shrinks by five francs. It’s like “making change” between one-dollar bills and five-dollar bills. You can see that as long as the currency manager is willing to buy British pounds and sell francs in unlimited quantity at 5:1, and also willing to buy francs and sell pounds also at 5:1 in unlimited quantity, then the exchange rate can never deviate from 5:1. The currency manager is always able to buy every franc in existence with the British pounds held in reserve, so there is never a danger of “running out of pounds” if the proper operating mechanisms are observed.

Sometimes the proper operating mechanisms are not observed, in which case you don’t have a currency board, but rather “a goofball who doesn’t know what he is doing,” with the usual unpleasant consequences. Unfortunately, this is often mislabeled a “currency board,” which causes confusion. However, it seems like most countries pretty much did what they were supposed to in the 1920s period.

Now, why do people want to hold francs? They want francs to use in monetary transactions. As people become wealthier and they want to hold more and more money, then of course they must obtain this money somehow. Eventually, typically through an intermediary like a bank, people will give British pounds to the currency manager and receive francs in return. That is the only way to get them. But where do they get the British pounds from? Obviously, British people aren’t giving them away. They are obtained in trade. A French person sells something to a British person, gets British pounds in payment, and brings these pounds to the currency manager to trade for francs. Or, they might borrow the pounds. However, this doesn’t happen in all foreign transactions. It is only the amount corresponding to the increased demand for franc base money. If French people didn’t want to hold any more franc base money, for some reason, they wouldn’t give their British pounds to the currency manager to obtain French francs that they don’t want. Instead, they would either a) buy some British goods and services; or b) buy some British assets like stocks and bonds.

We talked a lot about operating mechanisms earlier this year:

January 29, 2012: Gold Standard Technical Operating Discussions 3: Automaticity Vs. Discretion

January 15, 2012: Gold Standard Technical Operating Discussions 2: More Variations

January 8, 2012: Some Gold Standand Technical Operating Discussions

What about the British side? The amount of British pounds in existence is also exactly in line with people’s interest in holding pound base money, at the gold parity value. This is true whether or not the Bank of France holds British government bonds. If there were “too many British pounds,” for whatever reason, they would be taken to the Bank of England to be exchanged for gold bullion. Similarly, Britain’s current account balance reflects the domestic supply and demand for capital. It remains the same whether or not other central banks happen to hold British government bonds. If, for example, the Bank of France bought some British government bonds, that would seem to cause a current account deficit for Britain (net sale of British financial assets to foreigners). Not that it would matter, even if true. However, if a foreign buyer buys the bond, that means that a domestic buyer cannot buy the bond (in either the primary or secondary market), with their savings. What does that domestic buyer then do, with their savings, which now has no domestic demand? Ultimately, assuming that the domestic supply and demand for capital is unchanged, they buy a foreign asset of some sort, for example a French government bond. Thus, the Bank of France ends up with the British government bond and some private British investor ends up with the French government bond, and the current account balance is no different than if the Bank of France held the French government bond and the British investor held the British government bond.

THE EFFECTS OF THE GOLD-EXCHANGE STANDARD

The replacement of the gold standard by the gold-exchange standard has had three main results: 1. Under the gold standard a balance-of-payments deficit had the effect, through the transfers required for its settlement, of reducing the purchasing power—or one might better say the face value of income—in the country incurring the deficit. Under the gold-exchange standard, on the other hand, the total volume of purchasing power is in no way affected by balance-of-payments deficits, regardless of how large they are. Hence in so far as the total purchasing power of the debtor country is concerned, the gold-exchange standard creates a situation identical to that which would exist if there was no deficit.

NWE: We saw that during the “Classical” gold standard era pre-1914, there were in fact very large “balance of payments imbalances,” which is just another name for capital flows. The same is true of the “gold exchange standard,” which is just another variety of gold standard system, not actually all that much different.

The total volume of domestic purchasing power is, of course, affected in other ways—more particularly by the credit policy. It is at any given time the culmination of a great number of more or less independent factors. Domestic inflation, for example, can counteract and even reverse the shrinkage of purchasing power that is a consequence, under the system of the gold standard, of a deficit in the balance of payments. Granting that other influences play their part, there is still no denying that even where the volume of income is equated with the volume of national output—that is to say, even in the absence of inflation—the gold-exchange standard brings about a complete break between the volume of total purchasing power and the position of the balance of payments, and thus sweeps away the corrective influence of a monetary system based on the gold standard.

Since, under the gold-exchange standard, the balance of payments is no longer affected by the international settlements to which it gives rise, the only means, even under the most favorable conditions, for restoring its equilibrium is a systematic credit policy or dictatorial controls over international trade. Experience has amply demonstrated, however, that it is virtually impossible to restore by any kind of systematic and conscientious action the restriction of credit which the gold-exchange standard tends precisely to suppress. As to the high-handed manipulation of the balance of payments by such means as restricting purchases in foreign countries, establishing foreign exchange quotas for tourists, or even prohibiting short-term movements of capital, these efforts, to the best of my knowledge, have always failed.

NWE: We have here some confusion between credit and money, which is typical of “Austrian” flavored commentators. Credit is just borrowers and lenders coming to an agreement. A gold standard system does not “restrict credit” in any way. It adjusts the supply of base money to maintain the value of the currency at the gold parity. Borrowers and lenders are free to use this gold-linked currency as a basis for credit contracts, as they see fit.

The layman is sometimes amazed at how decisively a balance-of-payments surplus or deficit is affected by over-all variations in purchasing power. It would not be appropriate here to deal at length with the theory of this phenomenon. Let me just say, as a brief explanation of how it works, that any excess of domestic demand over domestic supply tends to cause the national output to be consumed within the country, whereas the opposite situation —an excess of the supply over demand—will cause a portion of the domestic output to become available for export.

The adjustments in the balance of payments that have taken place in France and Britain during the past ten years have always been the result of a contraction in the,volume of income, and never of any direct action by the authorities on the various elements of international trade.

2. Under the gold-exchange standard, any deficit in the balance of payments of a country whose currency is returned to its point of origin—that is, to the United States and, within the sterling zone, to Britain—by the central banks receiving it leads to a veritable duplication, on a world scale, of the basis of credit, subject, of course, to the other factors affecting the assets of the central banks. The process by which this occurs is as follows.

The currency transferred in settlement of the deficit is purchased, against the creation of money, by the banking system of the creditor country. The cash resources thus brought into being are remitted to the debtor country’s creditors. At the same time, the currency against which the creditor country created new money is reinvested in the debtor country; everything, in fact, proceeds quite normally, just as if the currency never left the debtor country in the first place.

By thus being transfused into the credit system of the creditor country while remaining in the credit system of the debtor country, the currency representing the deficit is in fact doubled, subject, of course, to the other factors affecting the volume of credit.

This process by which the gold-exchange standard is substituted for the gold standard, would have little effect on total purchasing power in a period when the various balances of payments were more or less in equilibrium, but it becomes a powerful stimulant to inflation as soon as international capital begins to move from country to country.

The analysis above was graphically and tragically illustrated by the events which proceeded and followed the recession of 1929. The financial rehabilitation of Germany through the Dawes Plan in 1924, and of France through the reforms carried out by Poincaré in 1927, brought on a massive influx of foreign capital into these two countries. Both of them, however, were operating under the gold-exchange standard, and it was the duplication of credit so characteristic of this system that caused the 1929 boom to assume such vast proportions.

NWE: Both France and Germany were enjoying a big economic recovery in the late 1920s, naturally the result of going from an unreliable floating currency to a gold standard system. Also, France had some big tax cuts in the 1920s, following the U.S.’s lead with the Mellon/Coolidge tax cuts. As noted previously, this made French and German bonds a lot more attractive, and made international investing a lot easier, so there was a big influx of capital. At the same time, the increasing demand for franc base money — naturally the result of both the expanding economy and the fact that the franc was now a reliable gold-based currency — meant that some of these British pounds and U.S. dollars would arrive at the Bank of France, to be exchanged for francs, because this is the mechanism by which the franc base money supply expands. This is all just the normal operation of a currency board, and does not have the effects that Rueff implies. Rueff also probably saw a big economic boom, the natural result of Low Taxes and Stable Money, and concluded that it was a product of this monetary system that he didn’t understand. There is a hint of “money multiplier” nonsense here too. Because the demand for franc base money is a result of people wanting to hold more francs, indirectly due to the expanding economy and increasing wealth (but having nothing to do with whether the currency manager’s reserve asset is domestic government bonds or foreign government bonds) the result would have been the same — the same amount of franc base money — if the system had been a pre-1914-style gold standard system or a “gold exchange standard.” As we saw before, a gold standard system (of either type) can expand by very large amounts to accommodate economic growth. In the 1775-1900 period in the U.S., the base money supply increased by 163 times!

January 9, 2011: The “Money Supply” With a Gold Standard 2: 1880-1970

January 2, 2011: The “Money Supply” With a Gold Standard

If the franc base money supply is the same, whether the central bank holds domestic government bonds or foreign government bonds as a reserve asset — and theoretically it would be, since there’s no particular reason why the desire to hold franc base money would change due to this factor — and, also the value of the franc is the same, because its value is fixed compared to gold either way, then it is an easy matter to conclude that the desires of borrowers and lenders to do business with each other would be the same, the desire to save and invest is the same, and the desire to buy or sell things would be the same. In other words, “credit creation” would be the same, investment would be the same, trade would be the same, and the “balance of payments” would be the same.

There was a similar extraordinary expansion of liquid assets in 1958, 1959, and 1960, as an aftermath of the movement of capital from the United States to Germany and France. In this case the results were and continue to be an abnormal rise in stock prices on world exchanges, marked overemployment, and a strong upward trend in prices.

The conclusion to be drawn from all this is that in a period when capital is flowing from countries with a key currency to countries whose currencies are not so privileged, the economic climate can be expansionist in the latter countries without being recessionary in the former. The leaders carry along the others, where there is nothing to check the boom, and the result is that as long as the migration of capital persists, all the countries affected by the gold-exchange standard are caught up in a powerful surge of expansion. This may be reflected in the economy or in the stock markets, and is clearly inflationary.

The foregoing remarks are in nowise incompatible with those theories which regard wage rises not accompanied by increased productivity as the origin of the inflationary process, and which set demand-pull inflation over against cost-push inflation. Although it is often difficult in such matters to distinguish cause from effect, there can be no doubt that the constant rise in over-all purchasing power both encourages and justifies the demands for higher wages, and at the same time eliminates the obstacles to their fulfilment.

NWE: It appears that France ran a current account surplus during this time, indicating that, whatever gross capital imports there may have been, these were matched by even larger capital exports. In other words, France’s domestic savings was in excess of domestic demand for capital.

3. The most serious consequences of the gold-exchange standard is, however to be found in the inherently unsound credit structure which it spawns. President Kennedy’s message pointed out that the $17.5 billion in gold held by the United States at the end of 1960 served to cover both the $20 billion of short-term foreign holdings and demand claims on dollars and the $11.5 billion requested by the present laws and regulations to cover the domestic currency in circulation in the United States. Now, I am not in any way implying that the existing gold stock is inadequate to ensure the stability of United States currency in present circumstances. Besides, President Kennedy has said that the amount of gold required as backing for the currency in domestic circulation could be reduced if the existing regulations concerning the guaranty of the domestic currency were changed, and he has, in fact, proposed that this be done. Further support for the dollar is, moreover, available in the form of a variety of as yet untapped assets, such as large drawing margins at the International Monetary Fund and extensive foreign holding.

The proceeding remarks do not, therefore, cast any aspersions on the the value of the dollar. They merely point to the inevitable conclusion that the application of the gold-exchange standard in a period of large-scale capital movements has saddled a considerable portion of the United States gold stock with an exceedingly high double mortgage. If a substantial part of the foreign holdings of claims on dollars were cashed for gold, the credit structure of the United States would be seriously threatened. This, of course, will not happen, but the simple fact that it could inevitably calls to mind that the depression of 1929 was a “great depression” because of the collapse of the house of cards that had been built on the gold-exchange standard.

NWE: The amount of gold held in a vault actually has little relevance to the “reliability” of any gold standard system. The real question is: are the monetary authorities able and willing to adjust the base money supply as necessary, to maintain the value of the currency at its gold parity. In other words, are they willing to adjust the supply of the currency to reflect changes in the demand for the currency, at the parity price? When people want to hold more currency, is this additional currency provided? When people want to hold less, is the base money supply reduced? This does not require gold in a box. In fact it doesn’t matter even if there is some gold in a box, as the U.S. most certainly had in the 1950s and 1960s. That’s why the Bank of England was able to operate as the world’s premier reserve currency in the 1860-1910 period while holding only about 1.5% of all the aboveground gold in the world, without mishap, and why the U.S. failed in this role although it held a huge amount of gold, equivalent to 44% of aboveground gold in 1941, and nearly 100 times as much gold in absolute terms as the Bank of England.

October 16, 2011: Heritage Conference on a Stable Dollar

In 1960, roughly the same set of circumstances was again present, and unless proper precautions are taken, the same cause could have the same effects. Consequently, the situation brought about by the doubling of the credit pyramid that has been built up on the world gold stock must be corrected while there is still time.

THE REMEDIES

The system of the gold-exchange standard, which had been in operation in many countries for a long time, can be dismantled only if two problems are solved: (a) The substitution of a system that will not foster or maintain the deficit of those countries whose currencies are considered by the central banks receiving them to be the equivalent of gold; (b) The elimination of the unstable and dangerously vulnerable situation resulting from the duplication of the credit structure erected on the gold stock of those same countries.

l. Under the system to be set up in the future, there must be no possibility of the creditor countries receiving in settlement of their debts a purchasing power never lost by the debtor countries. No central bank must, therefore, be able to lend a foreign creditor the currency against which it has already created purchasing power within its own monetary system. [footnote: In any detailed treatment of the subject, this statement would have to be tempered by certain reservations.]

As the gold standard, even when limited to external payments, differs from the gold-exchange standard in preventing the central banks from creating money except against gold or against claims on the national currency, it would fully meet the requirement mentioned above.

Some other system of multilateral clearing might also be satisfactory, on condition that the proceeds from the settlement of deficits not be made again available to the debtor country in the form, for example, of short-term loans on that country’s money market. Under a system of this kind, however, the immobilization of such proceeds, being voluntary and burdensome, would always be precarious and hence uncertain, whereas under the gold standard this would be an unconditional and inevitable result of the workings of the system. The European Payments Union gave an example of a gradual approach to a system based on the gold standard by the progressive “hardening” of its clearing procedures, that is to say, by the increased percentage of gold that had to be paid under the clearing agreements which it sponsored.

2. There is, unfortunately, only one way to eliminate the risks which fifteen years of the gold-exchange standard have left to the West, and that is to redeem in gold the greater part of the dollar holdings that have been accumulated by the various central banks. Only by doing this will it be possible to avoid the risk of a slump or a sudden deflation inherent in the duplication of the credit structure built on the gold reserve of the United States. The principal disadvantage here would be the sudden depletion of the gold reserve of the Federal Reserve System that would result from the redemption operations.

The situation is not so serious, however, as it might appear. President Kennedy himself referred in his message to the resources that are or could be made available if the dollar holdings had to be redeemed in gold. Unless, moreover, the gold-exchange standard had to be abandoned hastily as the result of a panic—and that is precisely what must be avoided—the dismantling process could be prop- organized so as to take place gradually.

3. To eliminate the duplication inherent in the gold-exchage standard would, however, reduce the liquidities of the central banks as whole by the amount of their dollar holdings. This, in turn, might bring them below the minimum levels required for the transaction of current international business. Such an eventuality could not be tolerated, and various proposals have been advanced to cope with it.

The best-known of these is the one advanced by Professor Robert Triffin of Yale, for concentrating the currency reserves of the central banks in the International Monetary Fund, where they would in effect become an international currency. As a means of remedying any liquidity shortage, the IMF would also be empowered to create and issue its own money, to an extent determined by an international authority in relation to the need for expansion. Depending upon the results of further study, Professor Triffin believes that this new money might be issued in such volume as would increase the aggregate stocks of gold reserves and currencies held by central banks by 3 to 5 per cent per annum.

This plan, which is very similar to that put forward by Lord Keynes in 1943, is worthy of attention because, through the concentration of cash resources that it would bring about, it would considerably reduce the liquidity requirements of the central banks. However, it also involves certain complications, since the new money that would be created would be only partially convertible and might in certain circumstances be destined to become a forced currency. Furthermore, the authority empowered to issue this money would, by reason of this power, be able in effect to impose levies on the economy of the member states.

The main reason why the Keynes plan was rejected in 1943 was fear of inflation. The reasons which caused it to be discarded still seem valid today, and apply with equal force to various other plans based on the same principles.

The refusal to accept an inflationary solution has led some commentators to advocate a higher price for gold as a means of increasing the face value of gold reserves. They point out that this price has remained immutably fixed at its 1933 level of thirty- five dollars an ounce, even though dollar prices are just about twice what they were then. A higher dollar price for gold, and thus also a higher price for gold in all the other currencies whose rates are based on the dollar, would, without any doubt, increase the face value of gold reserves, and thereby make it easier to eliminate the false cash balances that have resulted from the workings of the gold- exchange standard.

It would be imprudent, however, on the basis of calculations alone, to hazard an estimate of how much higher the price of gold should be, or even to assert that a rise in the gold price is unavoidable. In the first place, a much smaller volume of liquid assets would be needed if new methods of settlement were evolved through an expansion and improvement of the existing clearing machinery. In the second place, it is incorrect to assert that gold production is not greatly affected both by the price assigned to gold and by the movements in the general price level.

NWE: Here we have Rueff, led by his rather poor understanding of how monetary systems operate, traipsing down the same path as Murray Rothbard with their “revaluation of gold” nonsense that would amount to a huge currency devaluation — although more reluctantly than Rothbard. If you “revalue gold” at $50,000/oz., the value of gold doesn’t change to any large degree (it never has despite all the efforts of all the world’s governments), but the value of the dollar would. The value of the dollar would be only 1/50,000th of an ounce of gold! A “sound money” advocate that also advocates a catastrophic currency devaluation is not much good to anyone. The fact that neither Rueff nor Rothbard could figure out this rather obvious point does tell something about their understanding of these issues. Instead, how about if you look at the balance sheet of the Bank of England, as it returned to a gold standard system in 1821 and again in 1925, both examples which I conveniently provided for your use on this very page? We have done this before. It isn’t very hard.

March 26, 2011: The Persistence of the Bizarre

4. It is clear from all that has been said above that the elimination of the gold-exchange standard, although necessary, does present some difficult political and monetary problems which require considerable study and discussion. In such discussion it would have to be borne in mind that these problems are not exclusively or even essentially American. There is no possibility of solving them except by radically modifying the present system for the settlement of deficits in international trade, hence also the procedures of all the central banks. Although the gold-exchange standard is chiefly to blame for the balance-of-payments deficit of the United States [which didn’t actually exist, according to the chart above, which shows a modest current account surplus through the late 1920s and also the Bretton Woods period], this system was not initiated by the United States but by the international monetary conference which met at Genoa in 1922, and at which the United States was not represented.

What has been done by an international conference cannot be undone except by another international conference; but in any event, it must be undone quickly. A monetary crisis would endanger the financial rehabilitation that has at last been completed in all the countries of the West. It could bring on a serious recession that would have every prospect of becoming a “great depression.”

No matter what happens, the problem of the gold-exchange standard will be solved soon—either in the press of emergency or with quiet deliberation. We cannot allow it to be solved otherwise than with deliberation, which means that government action is necessary and urgent. If the action comes in time, it will spare the people of the West the disorder and suffering of a new world crisis.

NWE: Another problem of the time was that the “gold exchange standard” of the Bretton Woods period (in which Rueff was writing here) was having a rather hard time of it. This was because the U.S. was not operating the gold standard system by the proper operating mechanisms, but instead indulging in “domestic monetary policy” while trying to maintain the $35/oz. dollar/gold peg using rather heavy-handed coercion including various capital controls. This was causing all kinds of problems, which, like a lot of problems, expressed themselves to some degree in the “balance of payments.” Oddly, Rueff does not mention any of this, probably because he didn’t understand it. For the 1920s, and ironically for the Bretton Woods period as well, the Keynesian academics actually have a better description of events. We looked at Barry Eichengreen’s description of the 1920s here:

May 13, 2012: The “Gold Exchange Standard”

I think that Eichengreen’s description is fairly accurate, allowing for some fuzzy language and of course a heavy Keynesian bias favoring currency manipulation instead of stable money. But, history is history, and despite these flaws he manages to tell what happened.

Here’s a recent Bank of England paper, which describes some of the differences of how the Bretton Woods period operated compared to the pre-1914 world gold standard system.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/fsr/fs_paper13.pdf

Money quote:

The various IMFS regimes have involved different combinations of international and national frameworks. Members of the Gold Standard [pre-1914], for example, fixed their currencies to gold, allowed capital to flow freely across borders [i.e. “balance of payments imbalances”] and tended not to use monetary policy actively. So they gave up on the internal balance objective [i.e. “managing the economy” with funny money manipulation] to achieve allocative efficiency and financial stability. The Bretton Woods System (BWS) featured fixed but adjustable nominal exchange rates, constrained monetary policy independence [i.e. a little bit of funny money] and capital controls — effectively sacrificing the allocative efficiency objective [i.e. international capital flows] to allow greater control over internal balance and financial stability.

See what I mean? The Keynesian academics sum up things nicely here, with their heavy Keynesian bias of course.

So where does that leave us? I find that Rueff was a champion for libertarian values, at a time when centrally-planned statism and Keynesian money manipulation were growing ever more popular, as yet untempered by bad experience. This was admirable, and gets him enough credit in some sectors that people seem willing to accept all the other stuff unquestioningly. The same was true for Rothbard and also Milton Friedman. Friedman got a big following for his Free to Choose-type broad libertarian arguments, and people brainlessly sucked up his monetary manipulation nonsense (Friedman was an overt fan of floating, managed currencies and hated the gold standard system) without much question. Rueff was not so bad as that, thankfully. He maintained his commitment to the Classical principle of a gold-based currency. Still, the most alarming thing is not that Rueff said this or that silly thing — the world is full of people saying silly things — but rather that legions of readers and followers, in the decades afterwards, never asked the kind of obvious questions we are asking here and made the kind of obvious observations we are making here. But then, I have always maintained that the main reason that the world gold standard was abandoned in 1971 was not because of any inherent flaw — it had generated two of the most prosperous decades in U.S. and world history, the 1950s and 1960s — but rather that people forgot how it worked, and what it was for. Thus, they didn’t know how to maintain it (because they forgot how it worked), and they didn’t want to maintain it (because they forgot what it was for). This was also true of the gold standard advocates of the time, who had a rather poor understanding of how the system they advocated for was actually supposed to work, and how it did work in the pre-1914 period, or for that matter the pre-1944 period. I would even say that they forgot what it was for — namely to provide a currency of stable value — which is why they tend to drift into vague “freedom and honesty” arguments. Certainly nobody who wanted a currency of stable value would then argue that it should be devalued to some piteous level because of the amount of gold bullion that happens to be in a box somewhere. (Rothbard, among others.) Unfortunately, in the four decades since 1971, most gold standard advocates are still carrying around and quoting from these old and flawed books, their understanding hardly improved from the pathetic state of deterioration that was the primary cause of the end of the gold standard in 1971, rather than using the brains that God gave them. If that level of understanding was not enough even to maintain the world gold standard system already in place, a leftover from their forefathers, then how would it be enough to imagine and create a new and better world gold standard system, starting from the state of global monetary chaos that we now live in? That requires a much higher level of understanding. And you wonder why these guys never make any progress. They never will, if they keep doing what they have always been doing, like promoting Jacques Rueff as some kind of monetary genius for the ages.

It is really not hard at all to become much more knowledgeable about these things than Rueff, Rothbard, Triffin etc. ever were.

So do it!

People like Chuck Kadlec, Steve Hanke (a currency board expert), Steve Forbes (who is way more sophisticated than he lets on), the late Jack Kemp, and David Malpass are far more knowledgeable than these characters from the 1960s. Unfortunately, they don’t write as many books, which is why I say that we need a “shelf of books” that are fresh and new and correct, and not full of this antiquarian nonsense.

October 4, 2012: A Return to Stable Money Requires More Intellectual Gasoline

I think that those from the “Austrian tradition” today have actually come to realize some of these problems over the last ten years or so, at some level, which is why I now see a lot more sensible things from this group. For example, Lewis Lehrman’s gold standard proposal, as outlined in his book The True Gold Standard: A Monetary Reform Plan Without Reserve Currencies, avoids many of these pitfalls.

November 17, 2011: My Thoughts on Lewis Lehrman’s Gold Standard

Lehrman’s proposal, to summarize, asks for a fairly traditional sort of system in the U.S., much like what existed in 1910 for example, with gold coins (optional but not banned as was the case post-1933), and redeemability of base money into gold bullion. He also recommends, as the title suggests, that we do not use an extensive system of currency boards tied to “reserve currencies” such as the U.S. dollar or British pound, but rather that countries maintain what you might call independent gold standard systems.

I will also look later into some of the better recent academics with an “Austrian” sort of flavor, like George Selgin and Lawrence White. Initial indications are fairly positive. I would like to add their work to our “shelf of books.”

Although I think that most of the past “Austrian”-flavored criticisms of the “gold exchange standard” are basically fallacious, the system did have one big problem — all the currencies that were linked to the reserve currency via currency board systems were thus reliant upon the managers of the reserve currency to maintain a gold standard system. When the British pound was devalued and floated in 1931 (and 1914), all of the currencies that used the British pound as a target or reserve currency were thus almost inevitably caused to be devalued as well, simply because the existing system linked the value of those currencies to the British pound, not to gold directly. The same thing happened again in 1971, when the U.S. dollar was devalued and floated. In practice it is not quite inevitable that this should occur, and in fact most countries severed their dollar ties when the U.S. dollar was devalued on August 15, 1971, reflecting the initial intent not to follow the U.S. down the funny money path. But, in the ensuing chaos, they were not able to establish independent gold standard systems, and in practice all countries were sucked into the morass of devaluation and floating currencies, in 1914, 1931 and 1971, even those (like most European countries) which tried to resist at some level. Oddly enough, Rueff does not mention this much.

Thus, I agree with Lehrman that there is no particular good reason to set up another such system, and indeed that it should be avoided. Lehrman also has some funny terminology about “settling residual balance of payments deficits in gold bullion,” which is something of a linguistic holdover from Rueff (and also many other economists who use the same sort of terminology today), but I think that this basically means that the reserve assets would be gold bullion and domestic government bonds (or other high-quality domestic corporate bonds), which just means an independent sort of gold standard system such as the U.S. or Britain was using in 1910.

I also agree with Lehrman that redeemability would be a good thing. It is not strictly necessary, from a technical perspective, but the historical record of non-redeemable gold-based currencies is not very good at all. Usually they end up being floated and devalued within a couple years, even if this was never the original intent. This was true in 1971 for example (which was supposed to be temporary), but also in 1798 and 1914 in Britain or 1812 and 1917 in the United States. Remember that Britain and the United States were the most disciplined about these things, of all the countries in the world, which is why the British pound and U.S. dollar became “reserve currencies” in the first place. If even Britain and the U.S. could not maintain their monetary discipline without the process of redeemability, probably no political system would be reliably capable of doing so. It is easy to forget that Bretton Woods was officially put back together with the Smithsonian Agreement of December 1971, after only a few months of floating currencies, which everyone agreed was not in anybody’s interest. However, the Smithsonian Agreement did not have a redeemability element. In practice, the supposed commitment to maintain the dollar’s value at $38.02/oz. — in other words, a gold standard system — was never observed for even a moment. The dollar’s official gold parity was changed again in early 1973 to $42.22/oz., but the Europeans realized that this was also pure fiction, as the U.S. had no intention at all of actually managing the monetary base in a fashion to raise the value of the dollar to that level, and maintain it there. In practice, the Smithsonian Agreement wouldn’t have worked even with a redeemability element, because the correct operating mechanisms (i.e. managing the monetary base in the fashion described) were, at that time, largely forgotten.

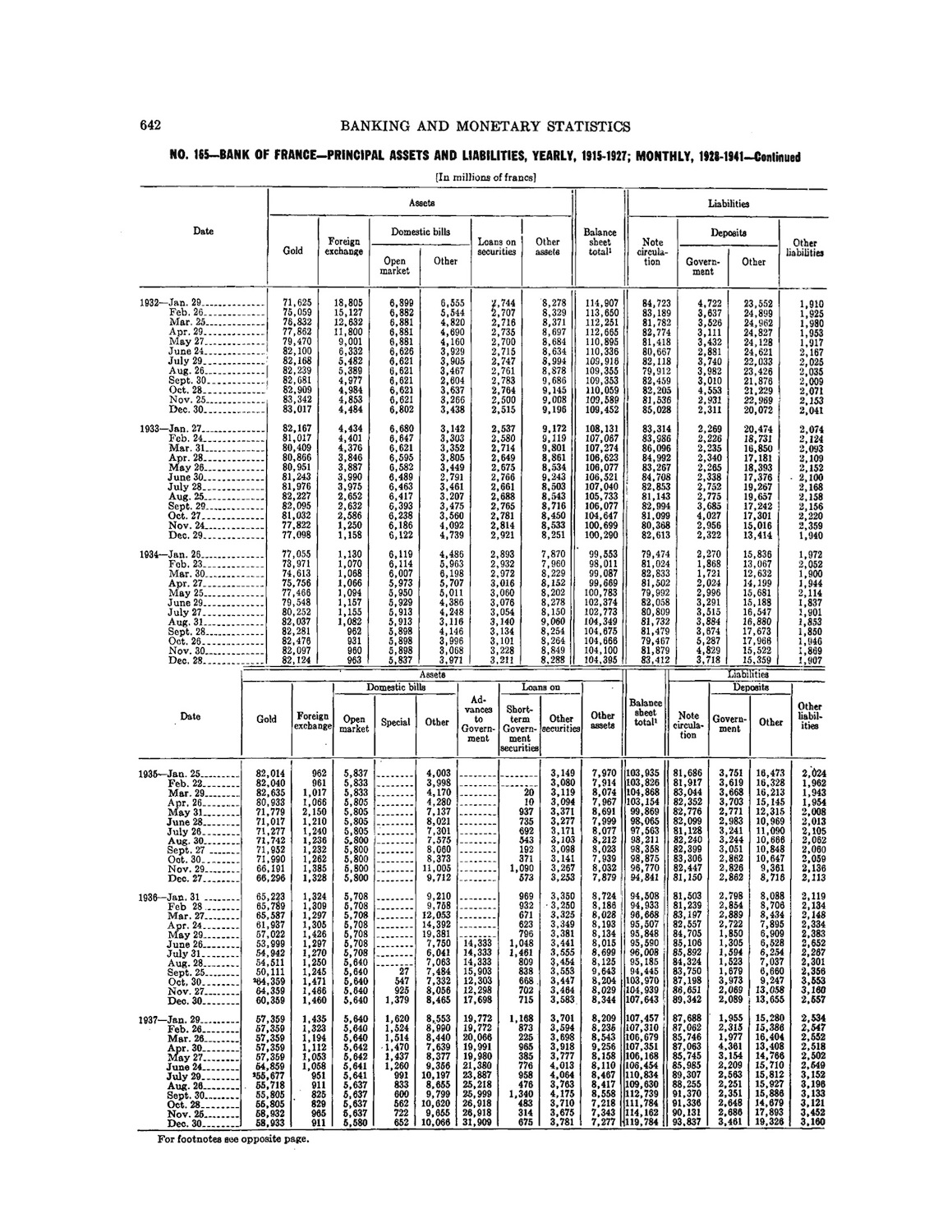

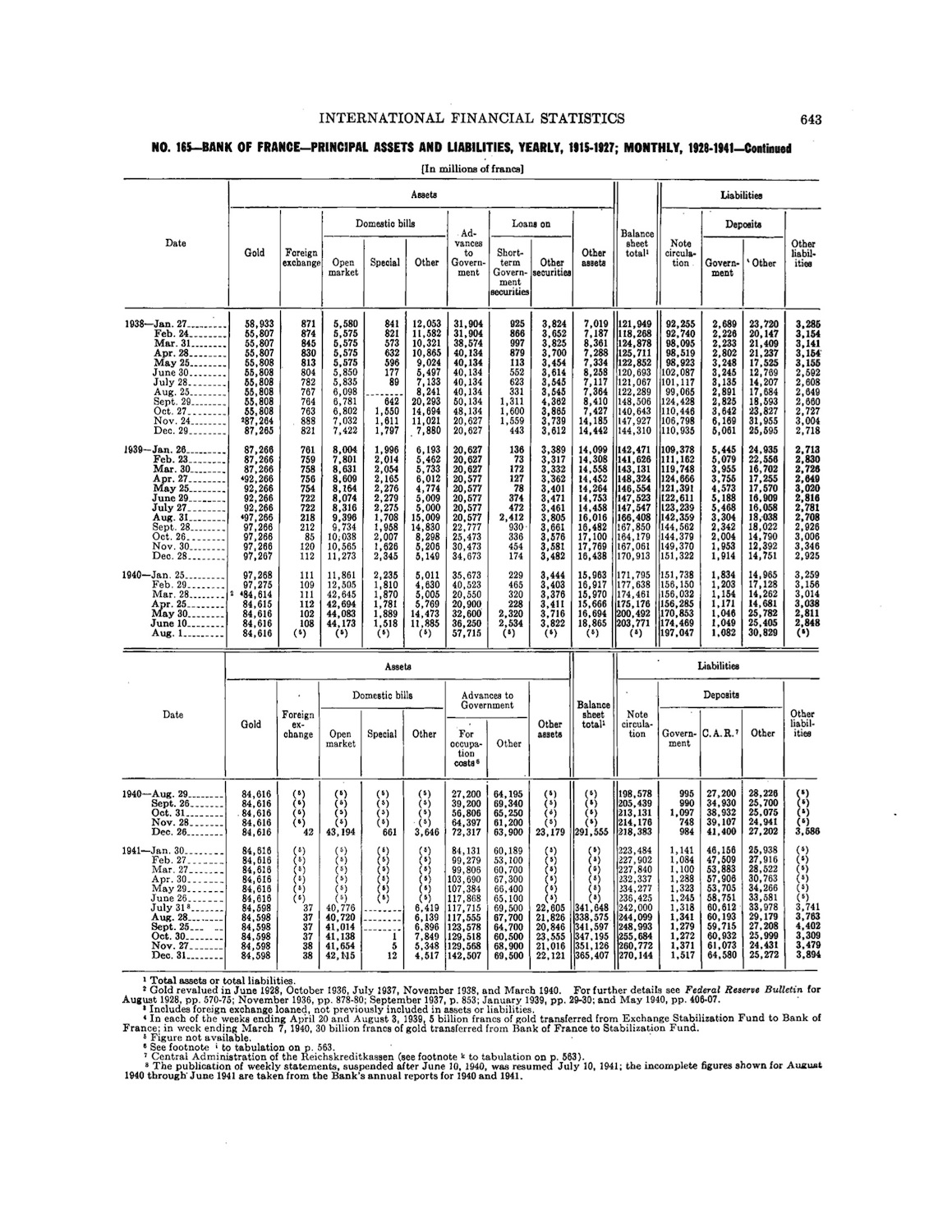

Lastly, since I know you are lazy as heck & etc. etc., here is the Bank of France’s balance sheet from 1914-1941. It may be useful to get some idea of what was going on in those days.