How To Make A Pile of Dough With the Traditional City 4: More SFDR/SFAR Solutions

July 17, 2011

First: Note that I have put this (and some previous) items under the “How To Make a Pile Of Dough With the Traditional City” series. This is because, these are basically instruction manuals for developers, or anyway builders. Maybe in the past, people built their own homes or at least oversaw the design, planning and construction. Today, we buy our homes like we buy our shoes. For most people, it seems as if nothing is ever actually built. Whether it is a 100 year old antique or something that was an empty plot six months ago, the buyer sees: a house. This, I think, contributes to the strange concept among many people today that nothing can ever possibly change, because they have never actually seen it change. It is always Just There. Developers, on the other hand, deal with these design issues on a daily basis. They are saturated with the experience that you go from a green field, or some repurposed urban land, and a wild idea, and then make a new reality. Hello developers??? Do you think you might make a bit more money if a) you make a lovely and attractive neighborhood, that b) supports a population density of 32,000 per square mile, instead of 8,000? I’m talking about selling four times as many houses, with the same amount of land.

Second, I think I will batch together here both “single family detached residential” (“SFDR”) and “single family attached residential” (“SFAR”), or what we usually call “townhouses.” When houses are built within a few feet of each other, it doesn’t really matter whether they are “attached” or not. For example:

These are “detached” single-family houses and duplexes, but they are so close together that they are becoming very similar to these Greenwich Village, New York brownstones, the classic “attached” townhouse. Note how much of the available land is taken up by that enormous roadway, sidewalks, Green Space between the sidewalk and roadway, and big front setbacks of blank grass. If the land is valuable enough to build this close together, isn’t it valuable enough that you can get rid of the giant roadway and fit in 50% more houses while keeping the same plot size? If you look at the distance between buildings, and then look at the distance from the front of one building, through the back yard, to the front of the next building, they look about even to me. In other words, the land taken by the building and the backyard together — the useful living area, or the Place as I term it — is about the same as the front setback/sidewalk/roadway in front, the Non-Place. This might seem “dense” but we’re letting 50% of the land go to waste!

October 10, 2009: Place and Non-Place

However, they do have one thing in common, which is that they are single-family residences for the most part, not big apartment buildings. There may be a few apartment buildings, such as large houses converted to 2-4 apartments, or dedicated apartment buildings which are roughly the same scale (up to ten units or so) as these single-family houses.

So, what we are talking about here is:

2) We want to incorporate off-street parking for at least one car per household, because we are envisioning this as a transitional format which can be used even if there is not a pre-existing transportation system which would allow someone to comfortably live without a car entirely.

3) We also want to be able to transition easily to a Traditional City no-car format, which in practice means Really Narrow Streets, and we want enough density (for example 32,000 people per square mile in Seijo, as we looked at previously).

4) The high density will also allow us to walk around the immediate neighborhood, so that you can shop, go to school, go to the bank, post office, local pub or restaurant, etc. without a car. This helps to eliminate the need for a second car, or at the very least reduces the use of the second car, and also allows businesses to be viable without having a parking lot.

5) This also leads directly to the ability to add a mass-transit option at a later date, because you can easily walk between your house and the train station/bus stop etc.

Let’s look at some ways to accomplish this.

First: it is not too hard to incorporate off-street parking for one car. We will look at a number of options in that regard. It is not too hard to incorporate parking for two cars, if you can stack-park them end-to-end. This is maybe not so difficult as it sounds, if the cars were interchangeable. If it doesn’t matter which car is on the “outside” and ready to use, then stack parking is fine. It is when we have “his and hers” cars that someone always ends up in the back of the garage. Even “his and hers” cars might be fine stack-parked if “her” car (the minivan) isn’t really used that much, because most neighborhood trips can be done on foot. We use it only once or twice a week. The problem arises when you want two cars parked side-by-side.

If it takes twenty feet of streetfront to park two cars side-by-side, and you have a twenty-five foot wide plot, then the entire streetfront becomes garage doors or automobiles. Even this is not such a problem if it is only a few houses with this characteristic. But, if all the houses have side-by-side parking for two cars, your street tends to end up looking like a storage facility (which it is — an automobile storage facility).

Storage facility.

Side-by-side garages under townhouses.

The problem lies in the ratio of garage doors (or outside parking) to total streetfront area. For example, this building also has a garage (on the right):

See the garage? However, the total streetfront of this building also has a lot of very inviting, lovely architecture so we are willing to overlook the ugly metal shutter door.

This house too has a garage door on the left, but it is only a small portion of the total streetfront so it is relatively innocuous.

Now, you might notice that these two examples don’t have a streetfront of 25 feet. That is something we see in the U.S. a lot. Plots tend to be very narrow and long, maybe 25 feet wide and 80 feet deep for a total of 2000 square feet. Why not make them forty feet wide and fifty feet deep, for the same 2000 square feet but much more streetfront? This also helps with things like windows. With a forty foot streetfront, you can have many more windows in the front and rear, so you don’t end up with the “railcar apartment” effect.

The answer to this question, it seems to me, lies with the width of the street. These Japanese examples above face Really Narrow Streets of about 16 feet side-to-side. The U.S. examples have 19th Century Hypertrophic type streets of 60-100 feet wide. Let’s say you have a pattern of 80 foot deep plots and 80 foot streets. The total width of the block and street is 240 (80+80+80) feet, and your street area/plot area ratio is 33%. Already you are giving up a lot of the total land area to streets. Now what happens if you have 40×50 plots? The total width of the block and street is 180 (50+50+80) feet, and your street is taking up 80/180 or 44% of the total land area. Yech! (When you include cross streets, the total street area ratio climbs higher still.)

However, with the Really Narrow 16 foot street, we can easily have a 40×50 foot plot. The math is 50+50+16=116 foot width, of which 16/116=14% is street area. Even though we need many more streets, because each house has 40 feet of streetfront instead of 25 feet, so the total street length per house increases by 40/25 or 60%. However, the total area consumed by streets is much less than the 19th Century Hypertrophic example — 14% compared to 33%, or less than half! Plus, 40×50 is a lot more usable as a plot area than the long, skinny 25×80 typical of the U.S. “townhouse.”

Also, the 19th Century Hypertrophic 80-foot-street version doesn’t have any way to go smaller than 2000sf or so. You can’t make it narrower than 25 feet, and you can’t make it less deep than 80 feet for the reasons described. Since 2000sf for a single family is actually a rather generous amount of space, we then have to transition to apartment buildings. However, with Really Narrow Streets you can go to 1000sf (25×40) or even 500sf (25×20) relatively easily, which allows us to stick with a single-family house format even at very high densities and land values.

A 40 foot streetfront would allow us to have even a big ugly two-car garage (20 feet) but we’d still have 20 feet left of lovely, inviting house front.

Typical Seijo street, about 16 feet wide.

Typical 19th Century Hypertrophic street. Waaay Tooo Wiiiide!!!!

How wide is this, from the outer edge of one sidewalk to the other? 80 feet is a fair guess.

West 19th Street, Manhattan.

Big two car garage, but with fifty feet of streetfront it is not too oppressive.

Another advantage of the Really Narrow Street, as pertains to offstreet parking, is that we don’t have the problem of “sidewalk cuts.” Normally, for every garage, you’d have to have a “cut” in the sidewalk to allow access to the garage. Here, we don’t have sidewalks, which allows for considerable flexibility regarding our parking options.

This problem is lessened if the garage door is only one car width (10 feet) wide. Then, you could have a thirty-foot wide plot, and the ten-foot door would be relatively innocuous.

I would also emphasize again the option of outside parking. This is the simplest possible solution, and one that is much less visually oppressive, in my opinion, than the typical garage door. The problem is that, unlike a garage, you can’t build over it, so in effect you lose the land area.

Side by side parking for three cars here. Imagine what this would look like with a three-car garage.

Cars as art.

Just a little patch of gravel is all you need. Parking for three cars here if you need it. Note the street width.

There is even a sort of hybrid, which is the “carport.” This is basically an open garage, with no door but you can build over it.

Tokyo again. This is a bit of an extreme example, but you can see here how we have parking for one car, without losing the space, and also without an oppressive garage door. Did you think I was kidding about 500 square foot plots? This is more like 400 square feet by the looks of it. The car itself adds visual interest.

This house is actually in North Carolina. Of course it is in a rural setting. But this is an example of the “house on pillars” approach. You could use the space beneath the house as parking. You see this often in Tokyo, but I couldn’t find a good photo.

Another “carport” solution, Tokyo. Look at the street width on the right. Once again about 16 feet.

We’ve seen some of these Japanese examples before. Now I want to add a few U.S. examples too.

These lovely 19th Century Victorians in San Francisco often have garages at street level. This is downplayed by the great big stair, which draws the eye up above street level to the decorative house above. This is something of a Hypertrophic solution, but it works here. With a 16 foot street width, the giant stairways would be a little odd, but it might work.

Garage at street level, big stair.

Garages at street level. These are mostly one-car width garages, but allow stack parking of two cars.

The space taken by the stair produces a natural setback in front of the garage, which allows outdoor parking of another car if necessary.

These are some really beautiful houses, but I think the basic format could be enlivened by the addition of one tree per house. There’s actually plenty of room there.

Look, for example, at the space from the right edge of the garage to the left edge of the adjoining stair. There’s actually about six feet there. Instead of bare concrete, this could be a patch of dirt where trees and bushes could be planted. That would help obscure the garage door a bit and also add a bit of verdure to the streetfront. Also, that big stair could be narrowed by a couple feet, which would allow a little more green to be added between the stair and the garage. You can see the tree on the right to get an idea of what I mean.

More garages. Here we have no setback, they are right up to the property line.

Garages here too.

The lively colors help make the garages less blah.

Here we have a little verdure between the stair and the garage, rather than just a wider stair. It helps.

More garages at street level.

Another garage here. These houses typically have nice backyards. However, you can see that they fulfill out “2000sf plot” design goal.

This house has the tree on the right and the bush between the stair and the garage, just like I suggested earlier. I think it looks better.

The SFDR houses in the East Bay area around Oakland have some similar design cues, notably the big stairway carrying the eye (and the visitor) up above street level. These are much closer to our “Small Town America suburban house” ideal, but in fact they are on plots as small as 1/20th of an acre, which is about 2000sf.

Here’s a solution which is simplicity itself — use the space between houses as outdoor parking! The parking is on the right there. If you have 10 feet between houses, you can easily stack-park three cars in there.

Again, parking on the right between the houses.

These houses have front yards, but they are not real big. See how much you can get out of about an eight foot setback here.

Parking on the left. See how easy that is? Now we don’t have any ugly garage door at all.

These plots are maybe 40 feet wide. So, fifty feet deep and we’d have our 2000sf bogey. You might have to shrink that front yard to fit it in 50ft. So what?

Parking on the left.

This is really the suburban variant of what we saw in the Victorian townhouses. We have a one-car-width garage (could be two cars stack parked) at street level, and a sort of stair that brings the visitor to the house which is built well above ground level. The streetfront is softened by lots of bushes and trees. However, the setback isn’t real big, just enough for one car width. We also get outdoor parking for one car in front of the garage. This could be about a 30ft plot width.

Parking on the left. A little overgrown. Once again we get that big stair. Look at the size of the front yard/setback here. That’s about right if you ask me. No need for anything more. Wouldn’t you rather have a larger backyard? You could make it a few feet smaller if you wanted to.

This looks like simple outdoor parking, to the right of the stair.

One car garage with townhouse above, big stair, and a little bit of greenery in between. This is perhaps a 30ft plot width. So, you could have 65 foot depth for 2000sf total.

Another garage on the right, this one with no setback and a nice deck on top.

These examples are all from Oakland, CA.

This garage looks like it sinks about three feet. The problem with a sunken garage is that you need about ten feet of setback for a ramp. However, if you have that setback anyway it is not a bad solution. This looks like about 30ft of plot width.

This is a rather ugly example, but note the sunken garage on the left.

More ugly examples of sunken garages. At least we avoid the “big garage door” look.

Here we can see the problem with “sidewalk cuts.” Look at the sidewalk here. Yes, it is that wavy black strip. About two thirds of it consists of “sidewalk cuts.” It is hardly recognizable as a sidewalk anymore.

Why not just get rid of it, as in the Seijo example? Also, with all these sidewalk cuts, onstreet parking has become impossible. You can’t park without blocking someone’s driveway. In that case, you can make the roadway narrower, because you don’t need to leave room for onstreet parking. Once you eliminate the excess roadway width and the vestigal remains of the sidewalk, you end up with something a lot like the 16 foot Really Narrow Street in our Seijo example.

Too bad these yards are so ugly. Why don’t they grow some flowers instead of chain link fences and blank green lawns? Americans are so dingy. One tree per house, planted in those green rectangles, would add a lot to this otherwise rather dismal neighborhood.

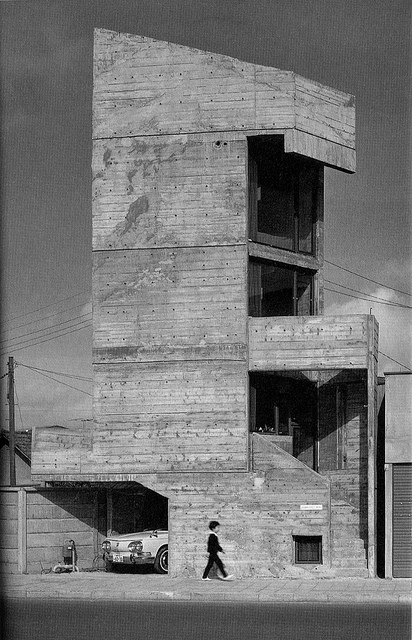

Now I will leave you with just a few more houses. The theme here is “Tokyo contemporary.”

A “carport” solution, Tokyo.

Tokyo, 2010 – Lucky Drops by Atelier Tekuto

A very long and skinny house, with simple outdoor parking.

Tokyo, 2010 – Natural Wedge by Masaki Endoh

Another “carport” solution. Apparently that’s the house built on top there.

Tokyo, 2010 – Sakuragaoka House by Nissyo Kogyo

Carport. Look at that street width!

Tokyo, 2010 – ÔOn the cherry blossomÕ house by Junichi Sampei / A.L.X.

Another contemporary with a carport solution. What’s the plot size here? I’d guess about 700sf.

Tokyo, 2010 – Reflection of Mineral house by Atelier Tekuto

Here’s that funny corner house again, with a person for scale (it’s small!) and also a shot of the street that it’s on (narrow!).

Carport with a Porsche. Note the street width. Another carport on the left. This is probably about a 1000sf plot, 25×40.

So, there you have quite a few examples of rather nice SFDR and SFAR houses, which could be built on plots of about 2000sf. They have parking for at least one and in most cases two or three cars. Remember to pair these designs with Really Narrow Streets of about 16 feet wide, as in the Seijo example, or even 12 feet wide like that last picture.

That’s it! You’re done! And you don’t even need a train system.

Other commentary in this series:

July 3, 2011: The New World Economics Guide to Men’s Fashion

June 12, 2011: How to Make a Pile of Dough with the Traditional City 3: Single Family Detached in the Traditional City Style

May 15, 2011: A Ski Resort Village

May 1, 2011: Let’s Take a Traditional City Break 3: Life With Really Narrow Streets

April 3, 2011: Let’s Take a Trip to the Skinniest House in New York

March 20, 2011: Let’s Take a Trip to Julianne Moore’s House

February 13, 2011: Let’s Take a Traditional City Break 2: More Really Narrow Streets Than You Can Shake a Stick At

February 6, 2011: Let’s Take a Traditional City Break

December 19, 2010: Life Without Cars: 2010 Edition

October 17, 2010: The Problem of Scarcity 3: Resource Scarcity

August 22, 2010: How to Make a Pile of Dough with the Traditional City

August 1, 2010: The Problem With Bicycles

June 6, 2010: Transitioning to the Traditional City 2: Pooh-poohing the Naysayers

May 23, 2010: Transitioning to the Traditional City

May 16, 2010: The Service Economy

April 18, 2010: How to Live the Good Life in the Traditional City

April 4, 2010: The Problem With Little Teeny Farms 2: How Many Acres Can Sustain a Family?

March 28, 2010: The Problem With Little Teeny Farms

March 14, 2010: The Traditional City: Bringing It All Together

March 7, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to Suburban Hell

February 21, 2010: Toledo, Spain or Toledo, Ohio?

January 31, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York 2: The Bad and the Ugly

January 24, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York City

January 10, 2010: We Could All Be Wizards

December 27, 2009: What a Real Train System Looks Like

December 13, 2009: Life Without Cars: 2009 Edition

November 22, 2009: What Comes After Heroic Materialism?

November 15, 2009: Let’s Kick Around Carfree.com

November 8, 2009: The Future Stinks

October 18, 2009: Let’s Take Another Trip to Venice

October 10, 2009: Place and Non-Place

September 28, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to Barcelona

September 20, 2009: The Problem of Scarcity 2: It’s All In Your Head

September 13, 2009: The Problem of Scarcity

July 26, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 3: How the Suburbs Came to Be

July 19, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 2: Downtown

July 12, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village

May 3, 2009: A Bazillion Windmills

April 19, 2009: Let’s Kick Around the “Sustainability” Types

March 3, 2009: Let’s Visit Some More Villages

February 15, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the French Village

February 1, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the English Village

January 25, 2009: How to Buy Gold on the Comex (scroll down)

January 4, 2009: Currency Management for Little Countries (scroll down)

December 28, 2008: Currencies are Causes, not Effects (scroll down)

December 21, 2008: Life Without Cars

August 10, 2008: Visions of Future Cities

July 20, 2008: The Traditional City vs. the “Radiant City”

December 2, 2007: Let’s Take a Trip to Tokyo

October 7, 2007: Let’s Take a Trip to Venice

June 17, 2007: Recipe for Florence

July 9, 2007: No Growth Economics

March 26, 2006: The Eco-Metropolis