Today, we have some “book notes” on the book Less than Zero (1997), by George Selgin, who recently retired from his position at the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives at the Cato Institute.

I use the term “book notes” to refer to comments on books that I have not actually read cover-to-cover, in detail. But, I think we can get a pretty good idea of the basic arguments, as illustrated by some lengthy quotes that I will provide. Basically, it is Nominal GDP Targeting, with a bit of a curveball argument for a lower NGDP target than some others prefer. A lower NGDP target implies a lower CPI or GDP Deflator, perhaps even one that is, on average, negative.

The Cato Institute has been a Monetarist hangout from its beginning in 1977. Some people think this is why Murray Rothbard, a cofounder of Cato, soon parted ways and helped establish the Mises Institute in 1982, which is much more gold-standard-friendly, just as Mises himself was always a gold standard fan. I’ve always considered Monetarism an error. In the case of Milton Friedman, its chief proponent, I think it was an intentionally subversive effort. Over and over again, Friedman said things that I do not think he really believed. Most politicians are no great economists, and Milton Friedman bamboozled them with pleasant free-market platitudes, as in Free To Choose. This indeed served a productive role against the big government Keynesian/Socialist movements of the time, in typical Controlled Opposition fashion. But, then Friedman would slip in his Monetarist doctrines, effectively splitting conservatives between Monetarists and gold-standard or “sound money” fans. In actual practice, he personally blocked Ronald Reagan’s efforts to move back toward a gold standard in the early 1980s. Reagan, born 1911, lived the first sixty years of his life during the Gold Standard Era that ended in 1971. He knew a good thing when he saw it.

Today, it is hard to tell whether economists, or institutions, are intentionally subversive (promoting ideas that they know are false and harmful), as I believe Friedman was, or actually in earnest — that is, they actually believe what they say. I will leave it to others to make that judgement.

NGDP Targeting, or “market monetarism,” is basically third-generation monetarism. (The first two generations didn’t work out so well.) As a book that is basically about NGDP Targeting, although with perhaps a little different target, Less Than Zero is basically a Monetarist book. Most of the rest is details.

I did not expect this book to be so heavily Monetarist in character. There is a different tradition, among some gold standard fans, who argue that a gold standard (or ideal Stable Money), will tend to result in falling prices, not rising. Basically, they argue that continuing productivity tends to bring prices down. Thus, if money is stable in value, and there is no inflationary impulse caused by inflationist policies that result in falling currency value, then we should expect to see a falling CPI. This would be a good thing — arising from increasing productivity — not a bad thing, such as a CPI decline that came about due to a recession or economic weakness (“decline in aggregate demand” according to Keynesian orthodoxy). Opponents of a gold standard, who are eager to impose their “easy money” hacks whenever there is a recession (or upcoming election), claim that a gold standard is “deflationary,” by which they mean, recessionary. This is not true, of course. But, there might be a time of prosperity when prices do indeed come down. This seemed to be the case particularly around the 1880s.

This is a good principle, but, unfortunately, like a lot of good principles, it has hardened into dogma among the rather thoughtless fans of “Austrian economics.” In any economy, some prices are going up, and some are going down, and some are not changing much. Basically, “prices,” by which I mean something like the modern CPI, PCE index or a GDP Deflator (all of them rather arbitrary and politically influenced as it is), might go up, down, or sideways under a gold standard regime, even if gold itself were perfectly stable in value. Prices for manufactured goods do tend to decline over time (or, quality goes up), with a currency of stable value, due to increasing productivity. Commodity prices have usually been rather stable over the longer term, with shorter-term fluctuations — although increasing productivity in commodities, particularly in agriculture, has led today to much lower apparent real prices than was the case before 1970. Wages have tended to rise, reflecting increasing productivity. With rising wages, prices for services tend to rise, along with prices for things like urban real estate, and the stock market. So, while a falling CPI is conceivable, it should by no means be expected.

Modern CPI or GDP deflator statistics generally date from after WWII. Even in the US, which was the pioneer in these efforts, the modern CPI dates from a revision in 1940. The GDP Deflator is from 1947. Most other countries introduced similar statistical indexes later than that. Most statistics from before 1940 (in the US) or 1950 (in other countries) are not very good. They can be useful, but they are nothing like a modern CPI index. Plus, during the 1940s, in the US and elsewhere, there were a lot of price controls and other odd influences on CPI indexes. A CPI that reflects “free market” prices dates basically from about 1950. Then, of course, the CPI has undergone many, many modifications since then, which stink rather heavily of political motivations.

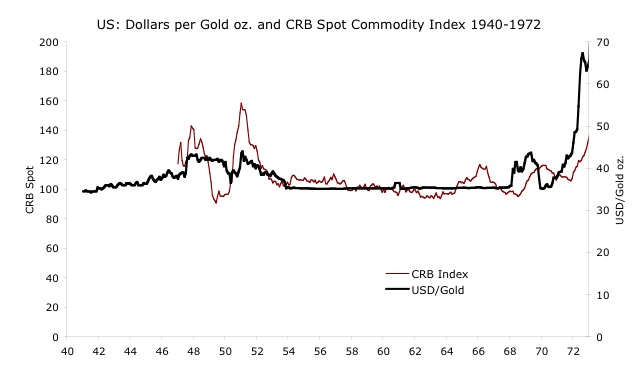

So, the era in which modern CPI statistics and also the gold standard overlap, is rather brief. Basically, it is 1950 to 1970. This gold standard period also had some rather significant deviations from the $35/oz. USD/gold parity, at times apparently exceeding $40/oz. in the free market.

But, if we take this period, what we see is basically: CPI statistics tended to rise, under a gold standard system, when commodity prices were also very flat, suggesting little deviation by gold from the Stable Value ideal that we always hope gold will reflect.

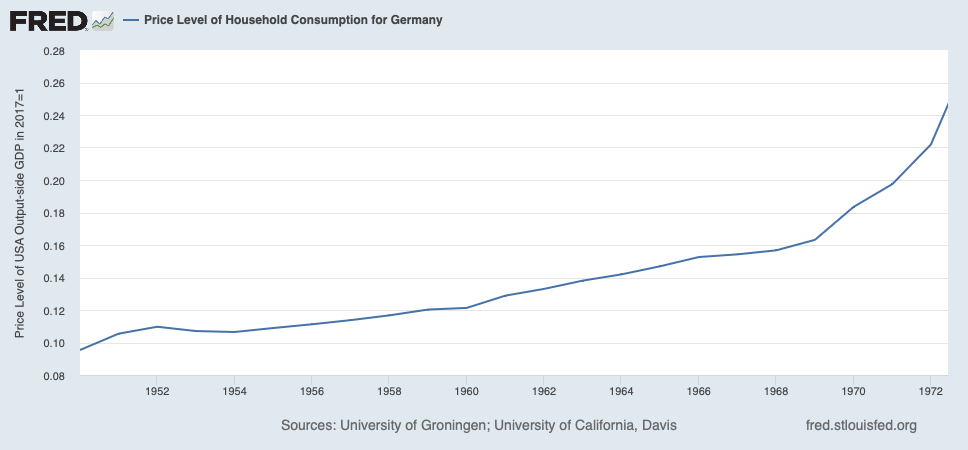

Here, from the “Penn-World Tables” we have “price level of household consumption” in Germany, a CPI-like figure. It rises from about 0.10 to 0.16, before a burst in 1970. That is a 60% rise in “prices” in Germany.

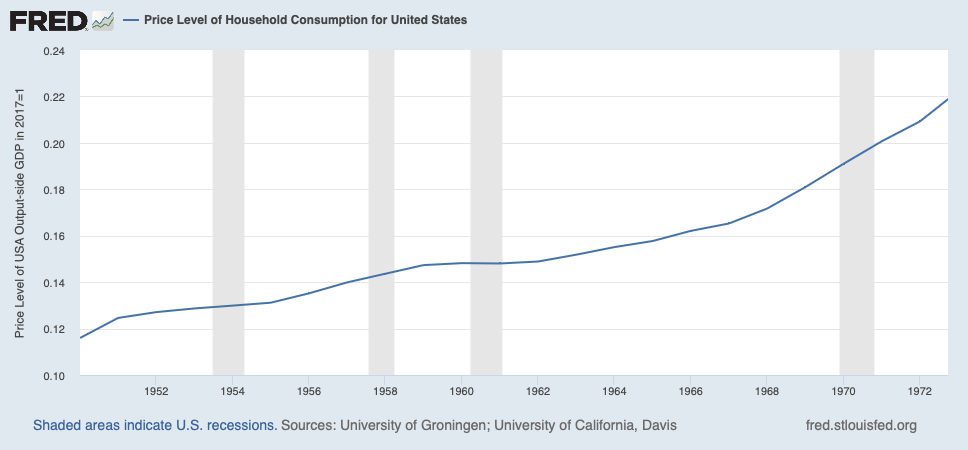

About a 63% rise in this figure for the US.

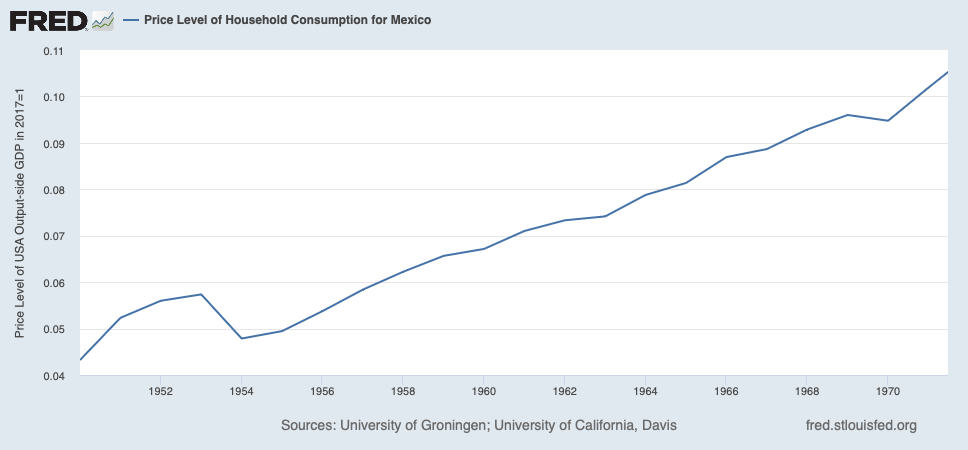

Mexico, about a 120% increase, while the Mexican peso was linked to the USD (and thus gold) at an unchanging 12.50/dollar.

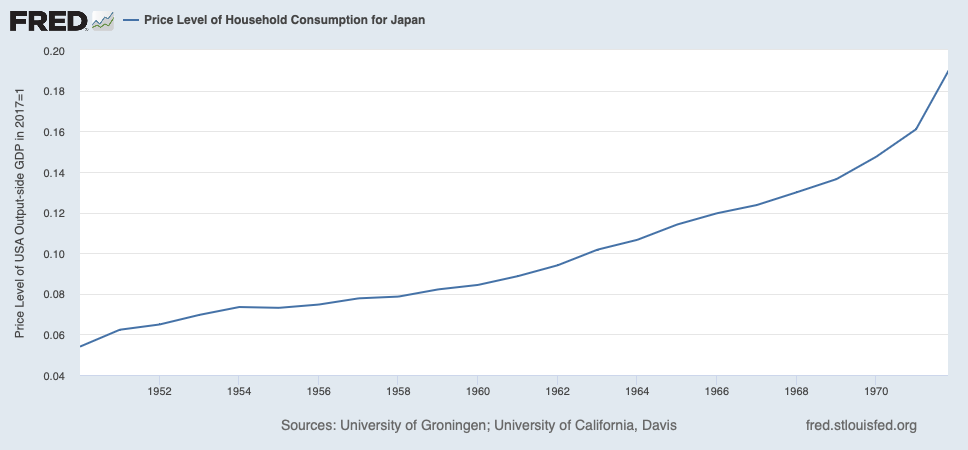

Japan, about a 170% increase.

So, when I say that, in a time of prosperity and increasing wages, under a gold standard system of idealized Stable Value, “prices” (a CPI) will probably tend to rise, I am not just making up stuff.

Commodity prices, as I said, were basically board-flat during this time, with a little ruckus in the early 1950s related both to the Korean War and also, some lingering USD instability following the Treasury Accord of 1951.

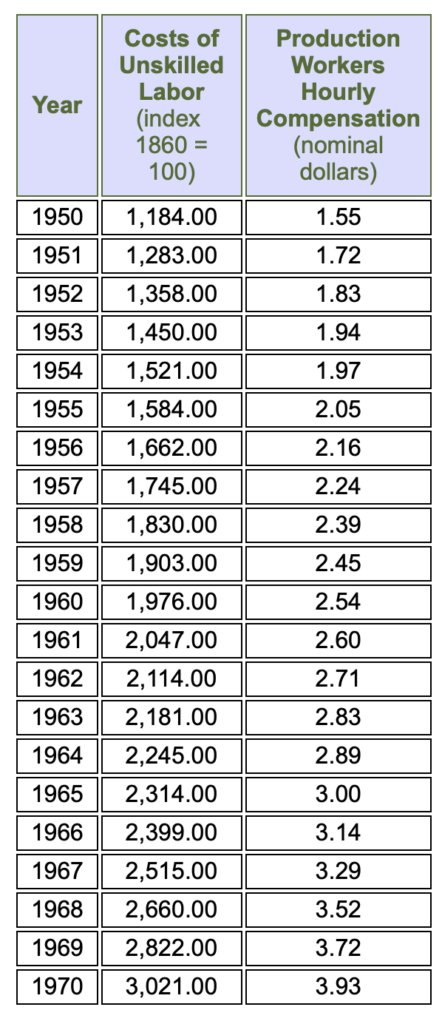

US wages during the 1950s and 1960s:

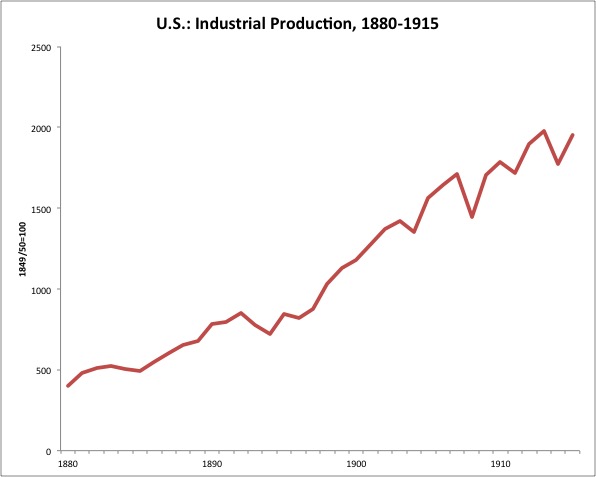

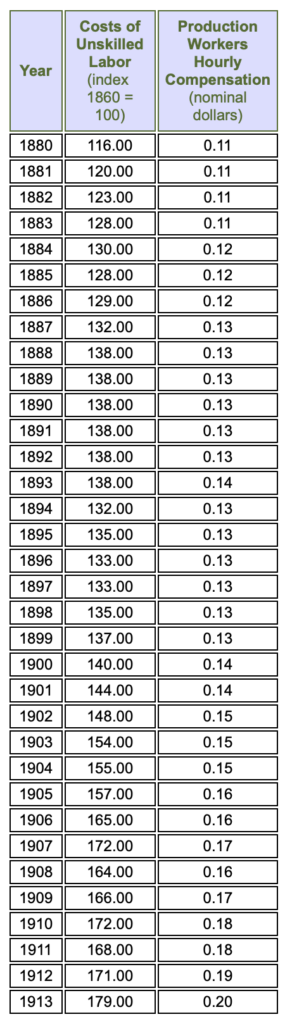

Most “price indexes” from before 1920 don’t amount to much. But, statistics on wages from that time are probably pretty good. In 1880-1913, the US was on the gold standard. In this time before the Income Tax, business was pretty good. Industrial production soared. This was the Gilded Age, a time of spectacular wealth creation.

But, wages were pretty flat from 1887 to 1900.

So, this may have been a time when people enjoyed their increasing productivity and wealth in the form of lower prices and flat wages, rather than flat (or rising) prices and rising wages, as was the case in 1950-1970. Both were gold standard eras of prosperity. (Over the whole 1880-1913 period, nominal wages nearly doubled.) So, it is definitely not one or the other. “Prices” (a CPI) might go up, down or be roughly flat, with a currency of ideal Stable Value.