Recently, I have been getting a number of inquiries about hyperinflation in Germany in the early 1920s. Mostly, this centers on the final collapse in 1923. But, to my mind, that is the least interesting part of the process. “Hyperinflation” is actually a spectrum, going from about a 20% CPI rise per annum (for want of a better measure), to the “billion-dollar banknote” periods that tend to get the most attention. I do not think that kind of very intense hyperinflation is in the cards for now, in developed countries. We may get there, but there are a lot of steps in between so there is no need to make any proclamations today. I think that much of the developed world may have some kind of “hyperinflation,” but it is likely to be more like Mexican hyperinflation in the 1980s, not Zimbabwe or Venezuela “children playing with stacks of old banknotes” kind of inflation.

As we can see, the German mark fell by 10:1 by the end of 1919. Then, it stabilized for some time, until mid-1921. Already by this time, the mark had lost about 90% of its value. Everything else was just the last 10%.

Germany, early 1920s.

Venezuela, 2019.

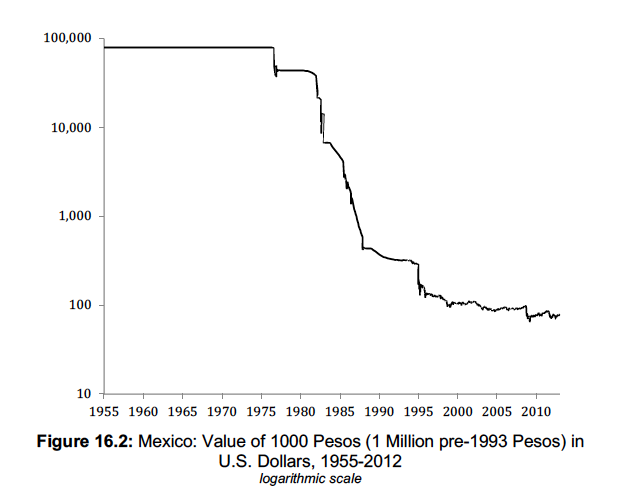

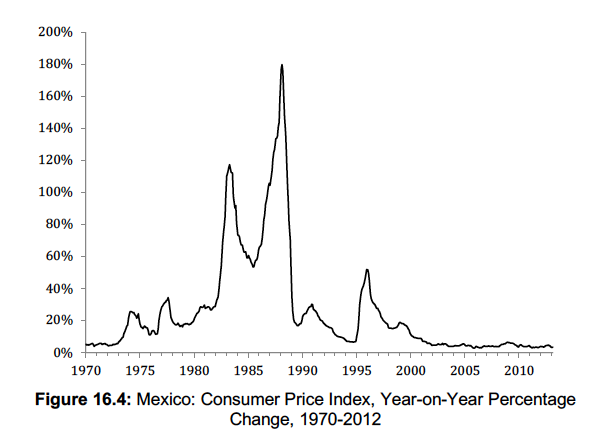

The value of the peso went from about 12.5 pesos/dollar during the Bretton Woods period, to about 3400/dollar after it was stabilized in the early 1990s. In other words, roughly a 250:1 devaluation, spread over a decade. There were never any “billion-peso banknotes.” During this time, the official domestic CPI had rises on the order of 60%-100% per annum, with peaks of 100%-200% per annum. This is certainly “hyper,” but not of the catastrophic hair-on-fire variety of Germany in the 1920s. Nearly all of Latin America had a similar experience during the 1990s. A number of years ago, I made a record of all the currencies in the world (for which data was available from the IMF), showing foreign exchange rates and domestic CPI figures. “Hyperinflation” of this sort has been very common.

October 13, 2013: What Is “Hyperinflation”?

October 19, 2014: A Brief History of World Currencies, 1949-2014

October 26, 2014: A Brief History of “Inflation,” 1949-2013

The Hanke-Krus Hyperinflation Table

So, I think it is good to get away from a “normal or Weimar” kind of black/white view of “hyperinflation.”

Nevertheless, there are several interesting elements of the German hyperinflation that are worth looking into, especially because this was a developed, industrial society without much prior experience of hyperinflation. Unlike countries with chronic currency disorders, its institutions were not established with this in mind. There was a sophisticated financial system. The historical record is very good. We can tease out certain themes, even if the magnitude might be much, much less.

I looked at the German hyperinflation briefly in the past.

October 10, 2010: Learning from Germany

February 27, 2011: Changes in Base Money Demand in Germany

June 9, 2011: How Germany Went Back to Gold

Here are some sources of good material on Germany:

When Money Dies (1975), by Adam Fergusen

Exchange, Prices, and Production in Hyper-Inflation: Germany 1920-1923 (1930), by Frank Graham

The Economics Of Inflation A Study Of Currency Depreciation In Post-War Germany (1937), by Constantino Bresciani-Turroni

Turroni is the most comprehensive.

But, I think I will start with the part that gets little attention: how the hyperinflation in Germany ended. It took all of one week. Much the same happened in Mexico, where the hyperinflation did not trickle down, but ended in a brick wall, when a link (albeit somewhat soft) between the peso and the dollar was established. Fixing the value of the peso to the dollar, and fixing the value of the Rentenmark to gold amounts to much the same thing.