We’ve been talking about “Nominal GDP Targeting,” which is a popular proposal these days among mostly right-leaning economist types, and which has broad support among “think tank”-type organizations that are involved in monetary policy.

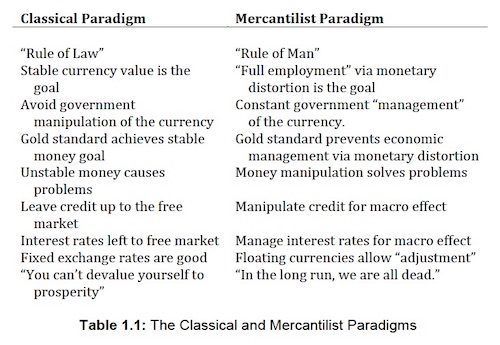

I said before that I am interested in reaching the generalist here. Thus, I want to describe some general features of this proposal. In Gold: The Monetary Polaris, I described the “Mercantilist” and “Classical” views of money. Nearly all academics today fall in the “Mercantilist” camp, and they really hate it when I label them this way, since it has connotations of 18th-century backwardness. That is, of course, why I like this term so much, because if you are going to stick the knife in, you should also twist it. But, there is a little more to this than just name-calling. Today’s money-manipulation schemes really do have a resemblance — a lot of resemblance — to what the Mercantilists of the 18th century were writing about and proposing.

Academics and other soft-money fans like to paint the Classical conception — the idea of a stable, neutral, unchanging money — of which the gold standard was the practical expression, as an old-fashioned and backward system. They are always claiming that various soft-money approaches are modern and sophisticated. But, actually both paradigms have been around for millennia.

Typically, the NGDP Targeting fan will go on for a while about “stability,” and use other words and phrases which sound sort of “Classical” in character. But, it should be clear that this is basically a Mercantilist approach, using monetary distortion to achieve certain outcomes (unchanging NGDP). In fact, it is a sort of extreme form of Mercantilism. We are now far beyond simply doing a little of this and that to avoid recession, applying a little “stimulus” or “restraint” to an economy that is otherwise left somewhat on its own. With NGDP Targeting, monetary manipulation achieves a sort of all-encompassing degree where, whatever happens in the real economy, monetary distortion is applied so that the NGDP figures are unchanging, like identical sausages being squeezed out in perfect regularity.

For example, let’s say a central bank becomes “easy” today when “real” growth is below 1%, and “tight” when it is above 4%, with a midpoint around 2.5%, or 4% nominal when you add 1.5% of “inflation.” NGDP Targeting is basically the same idea, but taken to the point where any variation at all from the 4% nominal growth target produces an immediate reaction.

I like very much these quotes from James Denham Steuart in 1767. Steuart, known as the “last of the Mercantilists,” envisioned a “statesman” (central bank governor) who would manipulate money and credit to produce “economic stability.”

He ought at all times to maintain a just proportion between the produce of industry, and the quantity of circulating equivalent [money], in the hands of his subjects, for the purchase of it; that, by a steady and judicious administration, he may have it in his power at all times, either to check prodigality and hurtful luxury, or to extend industry and domestic consumption, according as the circumstances of his people shall require one or the other corrective …

If money can be made of paper, … a statesman has it in his power to increase or diminish the extent of credit and paper money in circulation, by various expedients, which greatly influence the rate of interest. …

From these principles, and others which naturally flow from them, may a statesman steer a very certain course, towards bringing the rate of interest as low as the prosperity of trade requires.

And so we see the basic format of “modern Mercantilism” also reflected in the 18th century. When the economy is weak, “easy money” is applied. But, when the economy is strong and tending toward “inflation,” money becomes “tighter.” In those days too, they knew you couldn’t just step on the gas forever, or you would end up in hyperinflation. Variants on this principle became intellectually popular in the 1920s and have basically been applied since the 1940s. NGDP Targeting amounts to an extreme form of this principle, where no deviation from the NGDP target is tolerated, but instead monetary distortion is applied to eliminate the smallest variance. This requires a floating currency. Steuart, like others that followed, doesn’t have much to say about how his proposal would affect the value of the British pound.

Other forms of “monetary Mercantilism” or the “Soft Money Paradigm” include most anything that has a floating currency, such as: Interest rate targeting (basically a Keynesian framework), Monetarist quantity targets of various sorts, Taylor Rules, QE, and most anything that attempts to manipulate the economy somehow via monetary channels.

This is a very different concept than the “Classical” paradigm. In the Classical paradigm, an ideal currency is stable in value, unchanging, reliable, and free of human influence. The ideal currency is often compared to other weights and measures like the kilogram or meter. We can see that, whether the economy is booming or crashing, the weight of the kilogram or length of the meter does not change. We can also see that maintaining an unchanging kilogram and meter allows far more rational economic interaction, and thus allows greater economic health in general. Sometimes economies boom and sometimes they bust. But, there never has been economic bust that was caused by a kilogram or meter that remained unchanged. An unchanging kilogram and meter does not necessarily lead to an economic boom in itself, but it certainly provides a sound foundation and important prerequisite for one. Changing the weight of the kilogram and length of the meter can have a lot of unpleasant consequences, as it would derange all economic interaction, even if it seems like a good idea at the time.

Similarly, no economic bust in history has ever been caused by a currency that remained unchanging in value. Economic busts can happen for a great many reasons — and unstable money can be one of them.

In the Classical conception, growth and economic prosperity does not come from a regime of incessant monetary manipulation that squeezes NGDP from the sausage machine in perfect regular sections. It comes from investment, from innovation, from the individual struggles of individual businessmen to find better ways to combine capital and labor into more productive forms. It comes from individuals themselves bettering their skills so that they can provide services of more economic benefit. It comes from beneficial government statesmanship, in all of its many details: taxation, regulation, infrastructure spending, education policy, foreign policy, etc. But, it doesn’t come from jiggering the weight of the kilogram or the length of the meter.

George Gilder, in The Scandal of Money, did a wonderful job of describing how real economies are made up of individual stories: each businessman trying to figure out new and better ways of delivering economic value, and thus, a profit. When you start messing with the money, all the signals that are delivered via prices, profit margins, returns on capital and interest rates become deranged and confused, and cripple the process by which economic production takes place.

As a result of this, nominal GDP, in the Classical paradigm, can be wildly variable. When everything is going well, annual growth in nominal GDP (with a stable unchanging currency) can reach as high as 20%, which was touched for a few years by Japan in the 1960s. It might be at a more moderate level, like 7.0%, the average for the U.S. in the prosperous 1960s. It might even be a horrid disaster, like the U.S. in 1930-1932. Obviously, that should be avoided. But, whatever the outcome, the weight of the kilogram and the length of the meter is unchanged. Because, whether times are good or bad, why make things worse by messing up the kilogram and the meter, on top of that? In all of these examples, the value of the currency was unchanged, within the context of the gold standard systems used by the U.S. and Japan during those times.

The Classical paradigm is thus a lot more complicated. The NGDP Targeting people seem to think that everything can be made wonderful simply through the process of central bank money manipulation. In the Classical paradigm, everything affects the economy and thus everything is important (although some things are more important than others). Banking regulation is important. Immigration policy is important. The public school system is important. The tax system is important. Welfare policy is important. Public infrastructure spending may be important; or perhaps it is important not to waste money on it. And if something isn’t working well, you have to fix that problem. If your welfare policy is creating a growing underclass of unproductive and socially corrosive dependents upon the State, then you have to fix the welfare policy. You can’t fix the problem by jiggering the currency to produce an unchanging nominal GDP. When you put it in those terms, I think the absurdity of NGDP Targeting perhaps becomes most clear. Probably the NGDP people would say: “Yes, we agree, so go fix the welfare policy. We are not against fixing welfare policy.” But, if government policy is good, then what do we need NGDP targeting for? Why are we still jiggering the weight of the kilogram and length of the meter? And if government policy is bad, shouldn’t we fix it, instead of trying to compensate by currency distortion?

March 24, 2016: The Simple Simplistic Simplicity of Nominal GDP Targeting

November 18, 2016: JFK vs. Nixon = Gold vs. NGDP Targeting

Not only NGDP Targeting, but most “rules-based” proposals including (I would argue) CPI Targeting, Taylor Rules, or other notions, amount to variants on this Mercantilist principle.

July 26, 2019: Stable Value Is Our Monetary Goal, Not “Stable Prices”

February 12, 2018: “Rules-Based” Monetary Proposals Won’t Create Stable Money

April 7, 2017: What Are Our Stable Money Alternatives?

July 29, 2016: Don’t Be Fooled: “Stable Money” Means Gold

April 9, 2016: George Gilder Takes On The Big Question: What Is So Great About “Stable Money”?

January 21, 2016: “Nominal GDP Targeting” Is Just Another Red Herring To Divide Conservative Monetary Consensus

December 21, 2012: Embracing Stable Money Today

October 14, 2012: No Economic Crisis Was Ever Caused By Stable Money

January 19, 2012: What Is “Stable Value”?

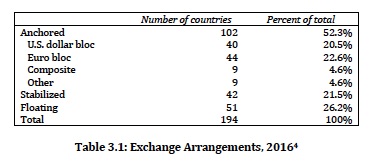

There is, however, a class of “rules-based” systems that are based on the Classical principle. These are “fixed value” systems. The most common “fixed value” system, in history, was the gold standard system (and its variants including bimetallic and even pure silver standards). But, “fixed value” systems remain common today too. According to the IMF, roughly half of all countries today have some variant of a “fixed value” system, commonly a fixed value with some international currency like the dollar or euro.

Many of these “anchored” currencies have problems, as they are “pegged” systems that are inherently prone to disaster. But, when this “anchoring” is correctly achieved with something like a currency board, then there is no “domestic monetary policy.” There is just a Stable Value policy. In practice, most countries find that it is important to maintain Stability of exchange rates with major trading partners. But, the basic principle is the same as the gold standard. Even if the dollar itself is not as Stable as we would like, nevertheless things go better if at least we all use kilograms that are the same weight, even if that weight is not quite unchanging. This only really works when the dollar itself is, at least, not an intolerable mess.

“Stabilized” currencies are also variants of a “fixed value” system, although with an element of variation built in, such as a “crawling peg” or some other arrangement. One reason for this is to allow the country to adjust for changes in the value of the dollar, while also maintaining exchange rates that change at a slow rate.

So, we find that “rules-based” systems, largely free of human intervention, somewhat like an unchanging kilogram or meter, are in fact quite common today. In the past, they used gold, and today, they use the dollar or euro. This is important, because it appears that fixed-value systems are, in fact, achievable by humans, and can last for a long time. The Athenian drachma was unchanged for six centuries. The Byzantine solidus was unchanged for seven centuries. The British pound was unchanged for almost four centuries. The Spanish silver dollar, extended to the U.S. dollar, was nearly unchanged (excepting some lapses) for over four centuries.

Any other kind of “rules-based” system, such as NGDP Targeting or a Taylor Rule, when applied internationally, results in every country having its own floating currency. As the above shows, countries don’t want their own version of the kilogram and meter that changes independently. They want to use the same kilogram and meter as everyone else, because business is easier that way. In the extreme case, imagine if the U.S. dollar entered a hyperinflation. Nobody would want to share that hyperinflating “kilogram.” They might not like it so much if the dollar’s value is going up and down, as part of an automatic system to produce an unchanging nominal GDP like sausages. They would have to break their dollar pegs and go it alone somehow, or form some kind of new currency bloc.

In other words, the system works best when the core international currency itself also remains as stable as possible. In the past, this was the gold standard system. Everyone could participate in it, because the main international currency wasn’t being destabilized in response to domestic economic conditions, which is what would happed from NGDP Targeting. Currencies were stable vs. each other, producing “relative stability,” and stable vs. gold, producing “absolute stability,” at least to the degree that gold achieved this perfect ideal. We not only want to use the same kilogram as everyone else, we also want it to be of unchanging weight, in absolute terms.