(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on February 8, 2023.)

In 1958, economist William Phillips wrote a paper which found a relationship between unemployment and wages. Less unemployment led to higher wages; more unemployment led to lower wages (or slower wage growth). People have been arguing over this ever since.

The basic problem here has been distinguishing between “monetary” and “non-monetary” causes of “inflation” — a topic we wrote about extensively in our new book Inflation (2022), because we knew this was going to be an issue.

You may have noticed the excessive use of quotes above. Unfortunately, even these words are rather vague, and I use them mostly because other people use them. “Inflation” to some people means a specifically monetary process (what we called “monetary inflation.”) For others, it means the change in some common price indicator like the Consumer Price Index, which can certainly be affected by “non-monetary” factors. Sometimes the same people go back and forth on these connotations from sentence to sentence. No wonder they are confused.

In our book, we make the point that prices (like the CPI) can be affected by “monetary” and “nonmonetary” factors. We all know that some countries (today Venezuela or Argentina) can have even “hyperinflation,” and this is entirely monetary in character. Also, we know that sometimes the supply and demand of individual goods or services (today eggs) can change prices dramatically. If this sounds very obvious, it’s because it is. Sometimes you can have both factors simultaneously. They even interact to a certain degree.

FEDERAL RESERVE

Economics today cleaves rather precisely along this “monetary”/”non-monetary” line. Unfortunately, this has left us with some people who insist that “inflation is always a monetary phenomenon,” and some people who tend to ignore monetary factors altogehter, and are wholly in the supply/demand framework, which they scale up to economy-wide levels and call “aggregate supply and aggregate demand.” Basically, these are Keynesians and Monetarists. Most economists today don’t call themselves “Keynesians” or “Monetarists,” terms from the 1960s, because it is a little like calling yourself a Whig or a Jacobin. It doesn’t advance your career, as an economist, to use such archaic language. But, they fall into these ruts nevertheless.

Phillips basically argued that, when there was a strong demand and tight supply of labor, wages (the price of labor) tended to rise. This is pretty simple stuff. Like most postwar Keynesians, he assumed a currency of stable value, so there were no monetary effects on wages. This was the norm during the Bretton Woods period, when most major currencies were linked to gold, with the US dollar at $35/oz.

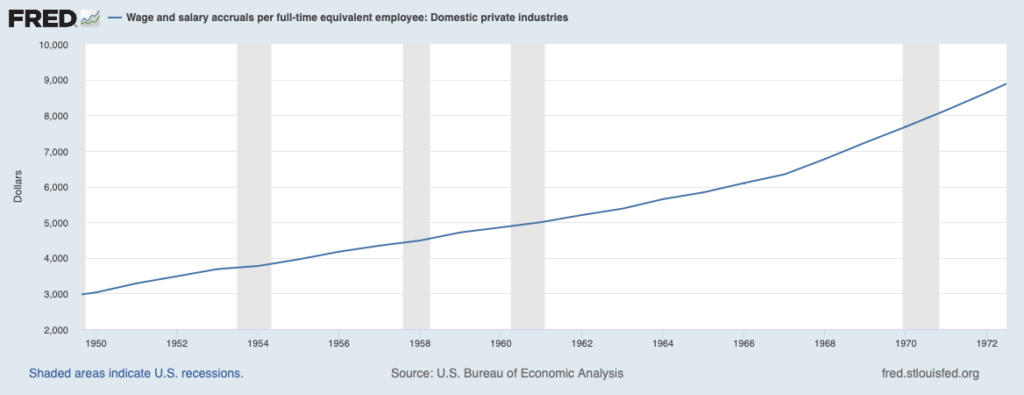

Phillips was right. A tight labor market really does lead to rising wages, just as supply and demand affects prices for all things. This is not a bad thing — rising wages is the whole point of “economic growth” and rising productivity. After decades of complaining that the American working class hasn’t had much real advance since the 1960s, aren’t low unemployment and rising wages a good thing? This might naturally lead to a higher CPI, since rising wages affects the prices of nearly all services. This higher CPI is thus a natural effect of a healthy economy.

But, this whole model — of a CPI being affected by the supply and demand of labor and actually, all things (”aggregate supply” and “aggregate demand”) — blew up completely during the 1970s.

During the 1970s, the US dollar lost about 90% of its value. In other words, it had about a 10:1 decline in value. During the 1960s, it was linked to gold at $35 under the Bretton Woods gold standard. By the 1980s and 1990s, it stabilized around $350/oz. Gold didn’t change — it was a change in the value of the dollar.

In other words, “inflation” (and the rises in the CPI) during the 1970s was “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” at least for that decade. It had nothing to do with the supply and demand for labor, although a generation of economists trained in postwar Keynesianism made that assumption anyway. This resulted in much stupidity during the 1970s, which was why things got so out of hand. The Phillips Curve degenerated into the idea that the 1970s inflation problem had something to do with — too much demand for labor, goods and services. They called it a “wage-price spiral,” “demand pull” or “cost-push” inflation. Actually, it was just prices adjusting to the new, lower value of the USD. But their solution was — not stabilizing the value of the dollar — but: More Unemployment! This was very dumb.

Since then, the Phillips Curve has been denounced over and over again. You can’t fix a monetary problem with More Unemployment. This has now turned into a new problem today, when wages are actually rising largely because of supply/demand conditions for labor, just as Phillips described in 1958. But also, the value of the USD really is lower, due to an aggressive Fed in 2020. Instead of “one or the other” (1960s vs. 1970s) we now have both “monetary” and “nonmonetary” factors at once. The result is that, instead of one group of economists being right and the other wrong, and then changing places; we have all economists somewhat right and somewhat wrong together.

So where does this leave us? Strong growth, low unemployment, and a tight labor market are good things. This might lead to a rise in the CPI. So what? It’s just the statistical aftereffect of a good thing. We don’t need to “solve” it, with more unemployment, because it is not a problem. In fact, we might just “make it worse.” We can just ramp up growth even more, for example with a Flat Tax reform that radically improves the conditions for doing business. In that case, the labor market might get really, really tight and wages might rise a lot. This is basically what was happening in the 1960s after a big tax reduction in 1964. (Employers didn’t like paying their workers more every year, which was one motivation behind the Immigration Act of 1965.)

However, we also want a currency of stable value, as we had when Phillips was writing in the 1950s and 1960s. In US history — actually, world history — this was practically achieved by linking the value of currencies to gold. Then, we do not have the problem of wages rising because the value of the currencies in which workers are paid is falling (Venezuela today). We do not have an “inflation” problem, even though the CPI might rise.

This is not hard to understand, but notice that nobody today seems to understand it. Did the Federal Reserve recently talk about things in the terms I just used? They did not. They mumbled about a lot of confusing nonsense.