We’ve been looking into the fact that commodity prices have fallen a lot vs. gold since 1971. This suggests to some that gold’s value has risen.

March 19, 2017: The Value of Gold Since 1971

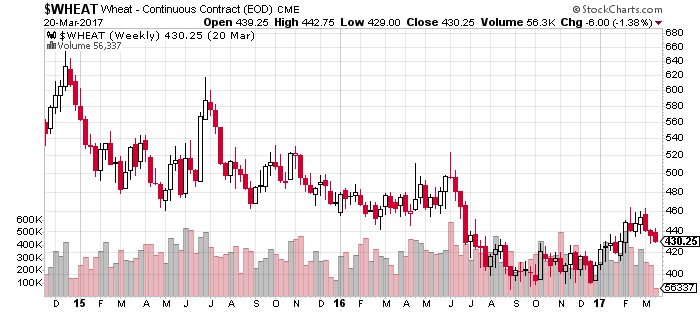

Instead, I propose that real commodity values have fallen. There are sixty pounds in a regular bushel of wheat. This is selling now for $4.30. That’s about seven cents a pound. That sounds pretty cheap to me. Absurdly cheap, actually.

I argued earlier that if gold rose in value, then crude oil must have risen too, because the value of oil, in terms of gold, is still roughly around where it was in the 1960s. If oil were much more valuable now than in the past, there should be some evidence of it in the real world, such as super-high-mileage cars. But, I see no evidence of that sort. In a similar vein, if wheat were really much cheaper today than in the past, we should see some evidence of it.

sWheatscoop. Kitty litter made of pure wheat.

There are 56 pounds in a standard bushel of corn, which you can buy for $3.63.

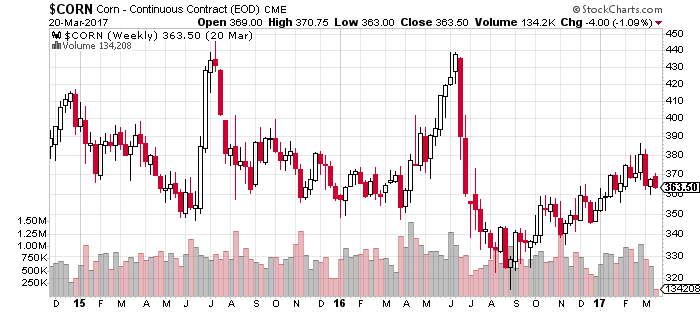

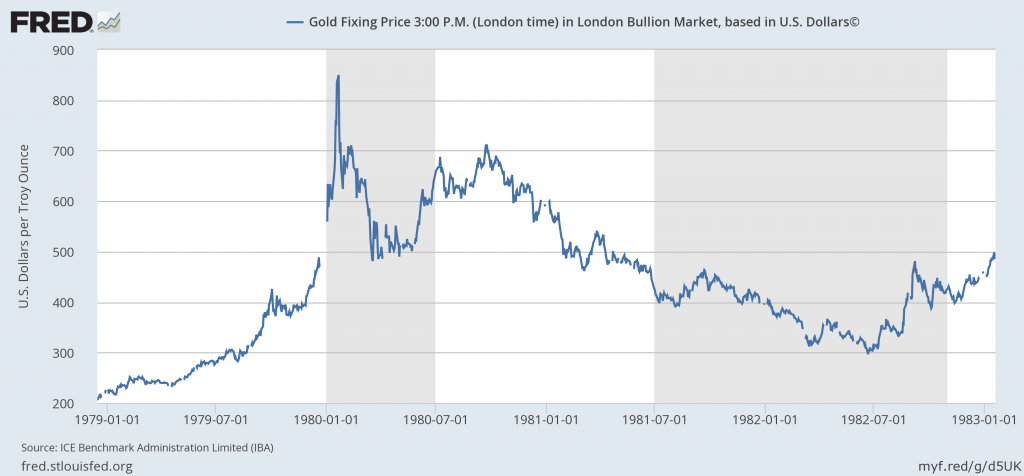

Let’s look at the CRB commodity index since 1947.

As we can see, it was pretty stable in the 1980-2004 period. Anyway, there is not a clear declining trend here, just localized declines around 1985 or 2000.

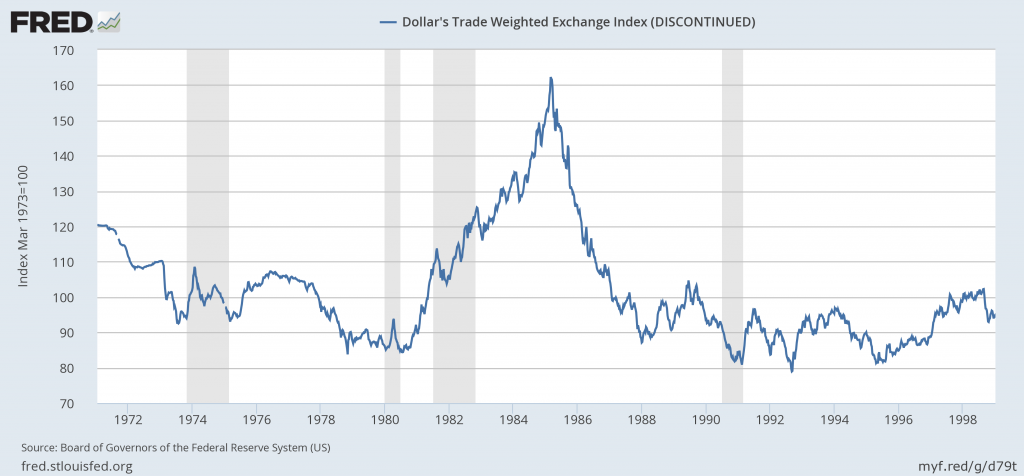

We can see that, during the 1980s and 1990s, there was no clear rising trend of gold vs. commodities. There was a bit of a falling trend, actually. They both had a sort of crude plateau during that time. We can see that gold tended to lead a little bit in 1980-2000, with commodities following about a year behind. This is a pattern that Roy Jastram identified over centuries of history. A change in currency value is reflected in the currency/gold ratio first, and then it flows into other commodity prices a little later. One reason that there was not a big spike in commodity prices when gold made a peak in 1980 was that the peak was so short. In any case, the fact that dollar/gold changes were confirmed by dollar/commodities changes in the 1980s and 1990s indicates that changes in the dollar/gold ratio reflected changes in the value of the dollar, with gold remaining somewhat stable.

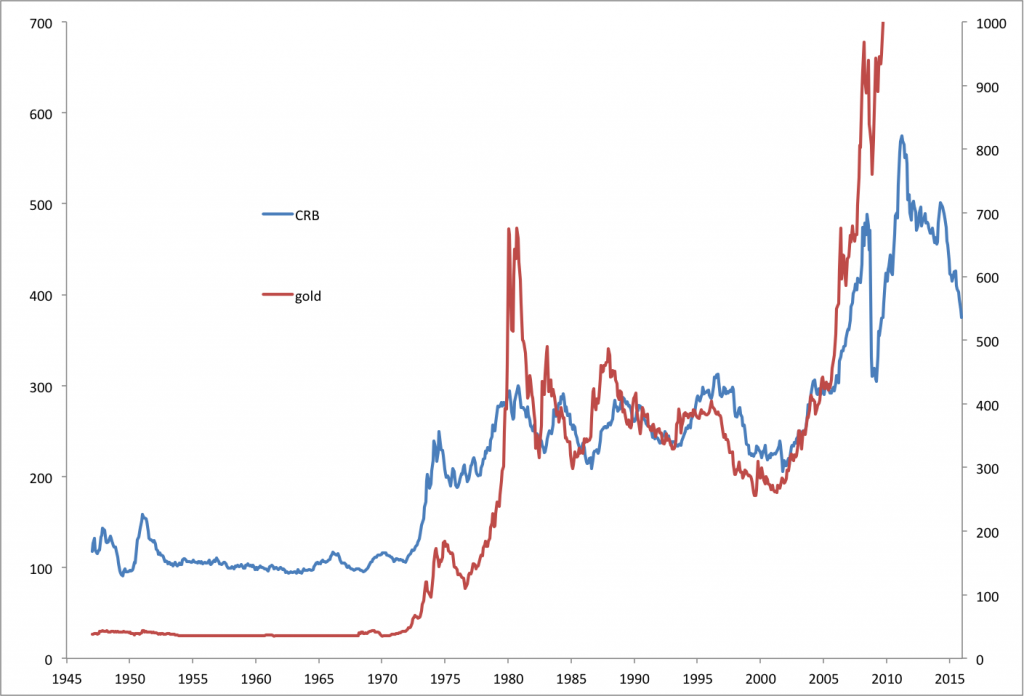

The “gold price” went from $380/oz. in November 1979 to $850 in January 1980, and back down to $500 in March 1980. So, there wasn’t twelve months for commodity prices to start to move. By 1981, the dollar was rising back towards $300/oz.

So, if gold did rise in value in the period 1970-present, it appears that this did not happen during the 1980s and 1990s. If it happened, it happened during the big dollar decline years, during the 1970s and after 2000.

I think that the dollar really was falling to the degree indicated vs. gold in 1979-1980; or, in other words, that gold was basically stable in value. Of course, I am a little biased here, because “innocent until proven guilty” is my policy regarding claims that gold is changing meaningfully in value. That notion is hard for some people to accept. This is largely the “money illusion,” the perception that the currency (dollar) is stable in value, and that nominal price changes represent changes in the real value of other things, not changes in the value of the money. As hard as it is now to believe, people in Germany during the hyperinflation 1919-1923 often thought the same thing — that the price of gold and foreign currencies was rising, not that the German mark was falling. Of course, currency collapses of this magnitude are very common. Here’s the Indonesian rupiah vs. gold in 1997-98 — which we know was 100% due to changes in rupiah value, not changes in gold.

Notice the similarity?

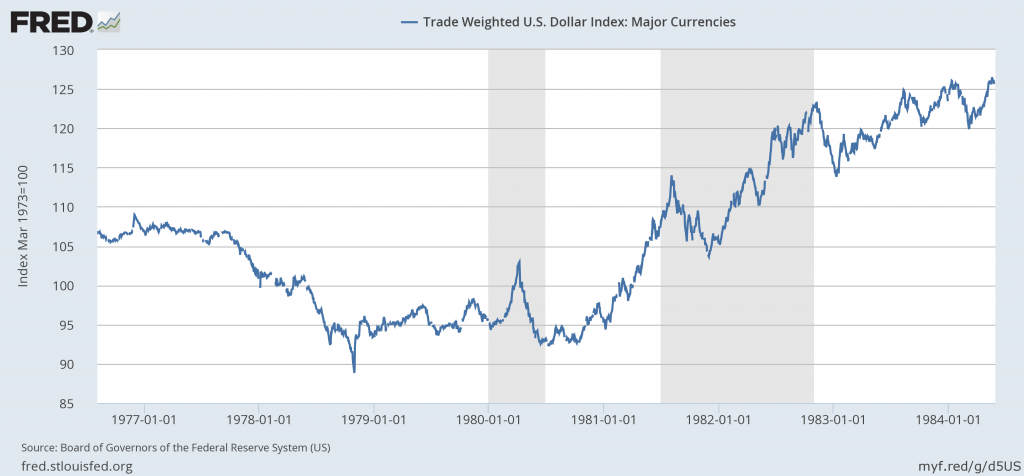

However, at the time, the dollar wasn’t falling vs. other currencies. I think this was because of a series of agreements that central banks would keep their exchange rates in line.

The same sort of thing happened in the first bout of dollar collapse, in 1971-1974. The dollar fell against other currencies, but it did not fall all that much, because other governments simply couldn’t tolerate the exchange rate swings, and took steps to keep exchange rates from changing too much.

We can see that there was a huge decline in dollar value, from $35/oz. to $190/oz. This was reflected in exchange rates, but the magnitude was much smaller. The dollar’s big decline in 1974, from $100/oz. to $190/oz., almost a halving of dollar value, isn’t reflected in exchange rates at all.

This is a chart of the CRB commodities index vs. gold since 1947. Commodities are relatively flat vs. gold in 1980 – 2002, showing, if anything, a modest rise. So, I don’t think gold was rising in value during this time. I don’t think it was falling either.

You could say that the big rise in the dollar gold price into 1980 represented a rise in gold’s value, as the object of an investment mania or something of that sort. However, if that was so, you might also expect a bust of some sort. The decline in the dollar price of gold after mid-1980 and into 1982 corresponded to a rise in the dollar index vs. other currencies, and also commodities. So, that does not appear to be a gold-only factor, but very much a matter of rising dollar value. It is difficult to identify any “bust” to match a “bubble” in 1980.

These topics are somewhat more difficult to talk about than I thought. There are a lot of subtle factors to bring up. I’ll try to summarize my views here. Maybe we will take up this topic again, and add more detail later.

I think that, since 1970, gold basically served the role that it had always served throughout history — as a stable measure of value. If you go back 500 years, one of the surprising things that turns up, again and again, is that gold appears to remain quite stable in value despite things that, it would seem, would cause it to behave otherwise. The 10x increase in silver production in the 16th century did not cause a meaningful change in silver’s value vs. gold (which did not have any such rise in production). Likewise, the 10x increase in gold production in the 1840s and 1850s seems to have had no effect on gold’s value. World War I doesn’t seem to have had any such effect, or World War II either, or the Napoleonic Wars.

Having said this, it is hard to be very definitive about it. It is more in the nature of a working assumption, based on two things: first, that there isn’t much evidence of changes in gold’s value over half a millennium, so a considerable burden of proof lies upon those who make such claims; and second, that there likewise isn’t much solid evidence of any such large-scale change in gold’s value after 1970. Certainly the behavior of gold and commodities in the 1980-2002 period suggests that gold’s value wasn’t changing much at all during that time.

It makes perfect sense to me that commodity values vs. gold would decline in an environment of worldwide currency depreciation such as we saw in the 1970s and after 2000. First, these events naturally favor commodity producers, with the result that aggressive investment and production follows. Second, when currencies are devalued, the value of wages vs. gold also declines. If nominal commodity prices were to rise to the same degree that currency values fell, such that the commodity/gold ratios remain largely unchanged, the nominal price of commodities would be largely unaffordable to people whose wages have not also risen to the same degree. Thus, demand would contract. To clear the market of commodities, real values (in terms of gold) must fall to a level that people can afford them. In other words, the pattern we see, of the major declines in commodity prices vs. gold taking place during periods of worldwide currency depreciation, is exactly what we would expect to see, if gold were stable in value.

The collapse of the dollar vs. gold in 1980 brought to the fore a lot of discussion about a new gold standard around 1980-1982. You have to imagine what things looked like then. There was “stagflation” around the world. The dollar price of gold had risen by a huge amount, but commodity prices had not followed alongside to the same degree. The dollar was not falling vs. other currencies. That was all they knew at the time.

Some people thought that gold had been basically stable in value, and the dollar/gold ratio (“gold price”) basically reflected changes in dollar value. Their recommendations were based on that hypothesis. Others were concerned that gold’s real value had risen considerably due to the general mood of panic and investment mania in gold, and made certain recommendations based on those hypotheses. I think we can look back, in a lot more detail than what I have done here so far, and see that gold’s value doesn’t appear to have changed that much — in other words, the first hypothesis is closer to the truth. Going over every piece of evidence would take a lot of effort, but perhaps enough has been laid out here to make things easier for those who want to examine these things.

For example, after the peak in 1980, if the dollar price of gold quickly collapsed back to $200/oz., with no apparent change in dollar value — no confirmation from falling commodity prices, no rising dollar vs. other currencies, no apparent “deflationary” effects in the broader economy like the 1982 recession — then we would have to say that the pattern did indeed suggest some kind of “bubble in gold” independent of these broader currency effects. But, that is not what happened.

Nevertheless, there is a cadre of dogmatists today who were influenced by those circa-1980 arguments, who still want to make the same old claims although the evidence has since shown that they were incorrect. They seem to argue that, if we went to a world gold standard, this would result in a decline in the value of gold, to perhaps a third of its present value. Thus, they recommend a new gold parity in the realm of $400/oz.

We saw earlier that, in the mid-1940s, people were uncertain as to what their currencies’ relationship to gold were, or should be. There wasn’t much of a market in gold bullion in those days, at least in the developed countries, which had a lot of wartime capital controls. We can look back now and see that the $35/oz. parity from 1933 worked just fine after the war as well. But, I can appreciate why people like Charles Rist weren’t so certain that this would work, in 1946 or so.

January 29, 2017: Book Notes: The Triumph of Gold (1952), by Charles Rist, #2

But, it seems that, even despite all the turmoil and capital controls of WWII, gold was still more-or-less stable in value during that time too. Rist’s fears proved unwarranted.

Nevertheless, even after the original worries that prompted Rist’s concerns faded with time, as experience showed that there was nothing to worry about, there seemed to be a cadre of dogmatists around Rist (and maybe Rist himself) who went on promoting solutions based on hypotheses by then proven wrong.

Fortunately, we don’t really have to make these decisions. If we really did adopt a new gold parity of $400/oz. (from around $1200/oz. today), and it turned out that gold’s value remained roughly stable from where it is today, that would create a disaster. We would in effect be tripling the dollar’s real value, with radically “deflationary” consequences. Ugh.

However, if we were to, for example, establish a new parity around $1200/oz. today, and it turned out that gold’s value really did decline to a third of its present value — which seems rather unlikely to me — then the dollar would, in effect, also fall to a third of its present value. That would be somewhat unpleasant, but it would not be such a terrible thing. Worse things happened between 2001 and 2011, and we lived with it. Once clear evidence arose of such a change in value, certain adjustments could be made. We don’t have to make guesses beforehand.

In general, I think that there might be some issues regarding parity prices should any new gold standard system be instituted. Besides the various arguments presented here, there are some issues today between “paper gold” prices and the supply and demand for real bullion. So, we might have a few years during which some adjustments would have to be made. That would be a little unpleasant, but not that big a deal. There were a lot of adjustments in the Bretton Woods parity prices too, in the 1945-1949 period. Then, things settled down and everyone enjoyed two splendid decades.

We should also appreciate that some of the people making these arguments might just be paid subversives. The people who fund their efforts intentionally want to keep the gold standard advocates divided, so that they can be more easily conquered by the funny-money people. I think Milton Friedman played this role in the 1950-1990 period.

Ultimately, nobody knows for certain what would happen with a new gold standard system. I “put my faith” in gold because it has always delivered great results. Even when other economic policy was a disaster — the Great Depression, for example — gold seems to have served as a reliably stable standard of value. In the end, you have to “put your faith” in something because nobody can know the future. If you don’t “put your faith” in gold, then you must put it somewhere else. For most people, this seems to be the opinion of those who are waved in front of their faces as “experts.” Yet, these funny money “experts” have a track record that is nearly as flawless as that of gold. They have failed in every instance.

December 7, 2016: The Gold Standard Vs. The PhD Standard

You can say “maybe this and maybe that” for decades if you want to. I don’t think it amounts to much more than a vague lack of confidence. This lack of confidence comes mostly, it seems, from the apparent lack of consensus. People want a herd to be a part of. They want “experts” to follow. They don’t want to make a decision or come to a conclusion. I think this is something that is learned in government schools. I am pretty confident that today’s floating fiat currencies will not be as stable a standard of value going forward as gold, because they are supposed to float, not be stable in value. They have a long history of wild swings in value, apparent in the foreign exchange market for example, and in their values vs. gold or commodities. There is no evidence of any change of approach that might produce a different and better outcome. There is a lot of evidence that currency instability, going forward, will get worse, not better. Central bankers really don’t have much ambition to even try to stabilize their values, or even much understanding of what this “stability of value” means. I think it is pretty funny that people who have lived with floating fiat currencies all their lives, including some pretty big mishaps, are all aflutter about some undefined risk that gold’s value will change by some amount large enough to be a problem, even though there is, I would argue, little evidence that such a thing has ever happened, including the period 1970-present. Is there evidence that floating fiat currencies’ values change enough to be a problem? Every day of the week.