One Nation Under Gold (2017), by James Ledbetter, is, pretty much, a gold-bashing exercise. I think it is propaganda: that is to say, not a forthright expression of an individual’s independent and informed view, but an intentional effort to mold public opinion to serve certain agendas. The tone and method is very much like The Power of Gold: the History of an Obsession, by Peter Bernstein, seventeen years earlier — so similar, indeed, that it sometimes seems that it could have come from the same team of ghostwriters. Apparently, Bernstein’s publisher devoted a quarter-million dollars to promote that earlier book.

“Worshipped by Tea Party politicians but loathed by sane economists, gold has historically influenced American monetary policy and has exerted an often outsized influence on the national psyche for centuries” read the first words of the dust jacket blurb, setting the tone for the rest of the book. In the preface, Ledbetter said:

“Fixing our money to gold and amassing great stacks of it is no more a guarantor of sustained economic health than a witch doctor’s potions. And, as with religion, what gold believers do can often resemble, in the eyes of the less devout, madness and destruction. From the earliest days of the American republic, gold blinded men from seeing the financial realties around them. And it brought with it all manner of fraud and false hope, gold by-products that are still with us today. … To avoid gold’s false paths, we need to argue with the past, to test the assumptions that are too often and too casually passed uncritically. This book, I hope, is that argument.”

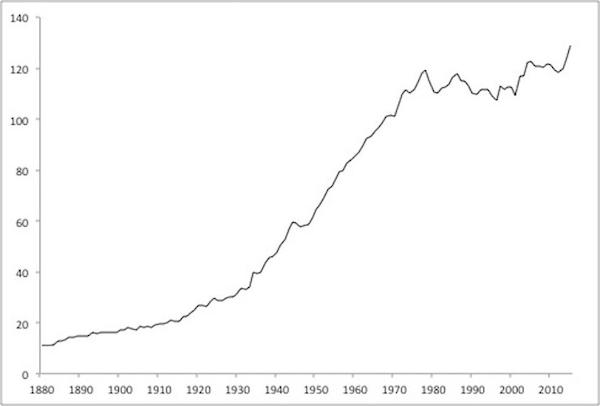

And yet, the United States embraced the ideal of an unchanging currency based on gold in the U.S. Constitution, and maintained this commitment for nearly two centuries, until 1971, having only one devaluation along the way, in 1933 — the best record, over that time period, of any major country. The result was that the U.S., which began as thirteen war-torn colonies east of the Appalachians with a population of under three million and a highly imaginative form of government, became the world’s superpower, the most economically successful country of those two centuries, along the way adding thirty-seven new states. If adherence to the principle of gold-based money was a “false path,” how did that happen? Since leaving gold in 1971, the results in the U.S. have not been so hot. Paul Krugman, on the Left, once called it “The Age of Diminished Expectations.” Tyler Cowen, on the Right, called it “The Great Stagnation.” During the period when the U.S. adhered to gold-based money, not even a Civil War and a Great Depression could long delay its upward trajectory to world-dominating greatness. Since 1971, that trajectory seems to have disappeared of its own accord.

U.S.: Wages of production workers, adjusted by official CPI, 1880-2016

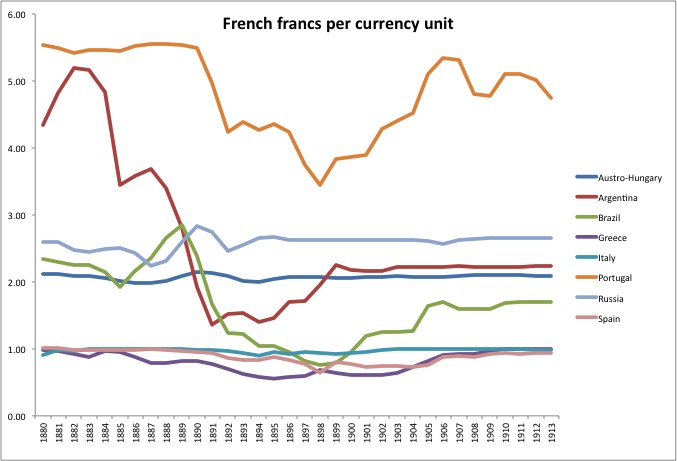

The United States was not the only one to embrace gold. This was a commonly held ideal among all governments, even if some did not quite have the discipline to actually do it. In the late 19th century, the U.S., Britain, France and Germany all had reliable gold-based currencies of unchanging value, and also, between them, ruled the world. Italy, Greece, Spain, Portugal, Argentina, Brazil and Chile had floating fiat currencies. Not one of them rose to challenge those that maintained gold-standard discipline. In the 1950s and 1960s, the U.S., Germany and Japan all had currencies that remained unchanging in value vs. gold. Britain, France, Brazil, Argentina, and many others had less reliable currencies. Guess which ones had the most success during that time? It’s an easy guess.

This is the past that Ledbetter should attempt to argue with; instead, he acts as if it didn’t exist. The general method seems to involve focusing on some historical particulars in great detail. This can be a bit of a distraction: the flip side is that much is left out. This also establishes credibility — it seems that the author has done a lot of research. Along the way, an effort is made to establish tenuous ties of association with various sorts of seemingly unsavory elements, all the while rather expertly avoiding saying anything that is factually incorrect. Here is a particularly obvious example:

“In March 2011, Utah became the first state to pass a law altering its definition of “legal tender” to include silver and gold. The law recognized silver and gold coins issued by the federal government as legal tender, and removed certain state taxes from their transfer. The bill was laden with the symbolism of mining days old and new. It was drafted by Larry Hilton, chairman of the Utah Precious Metals Association and also a Tea Party activist; when the governor signed it into law, a local real estate financier named Wayne Palmer handed a set of commemorative gold and silver coins to the state as a gift. Here, too, the line between populist energy and illegal activity is not always clearly drawn; less than a year later, the SEC charged Palmer with running a Ponzi scheme that defrauded investors of tens of millions of dollars.” (p. 333)

Huh? Wayne Palmer made a gift of commemorative coins; he later ran into difficulties with the SEC. Why do we care about commemorative-coin-gifters? No honest historian would. This example supposedly is to inform us that “the line between populist energy and illegal activity is not always clearly drawn;” what it actually shows is that people who make gifts of commemorative coins might also have shady businesses. The general effect is to associate Utah’s law declaring U.S. Mint coins as “legal tender” with Ponzi schemers. (U.S. Mint gold and silver coins are already legal tender under Federal law, and have been since 1985.)

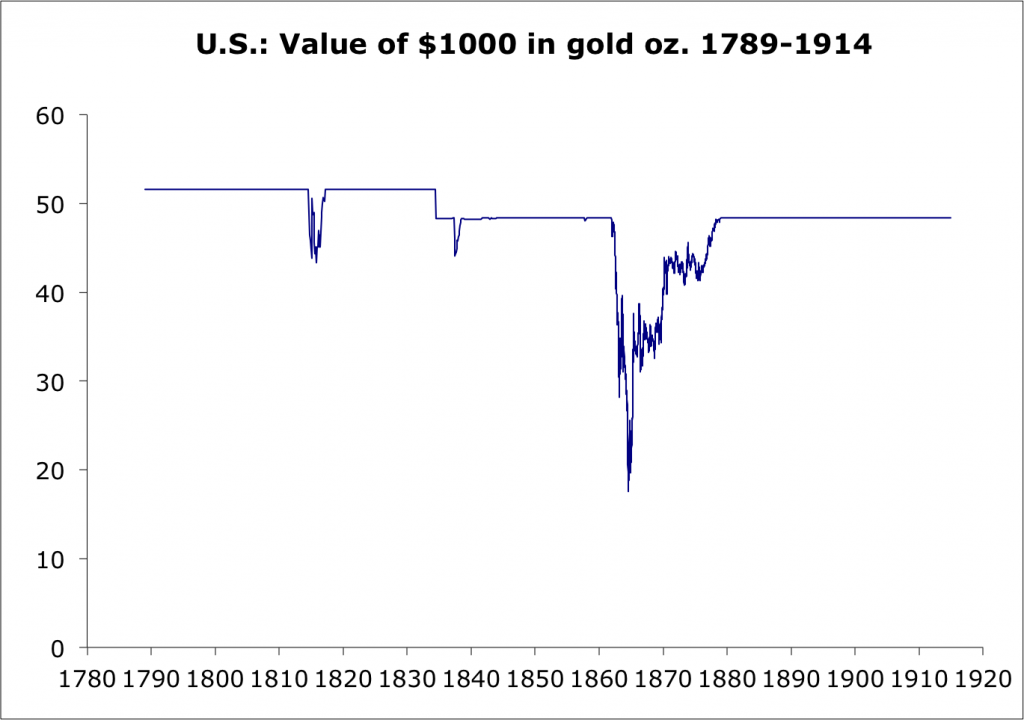

From 1789 to 1914 — 125 years — the U.S. dollar’s value was around $20.67 per ounce of gold. Actually, it was, at first, defined as 24.75 troy grains of gold ($19.39/oz.), and changed in 1834 to 23.2 troy grains ($20.67), in a minor adjustment within the bimetallic system of the time. The dollar floated during the Civil War beginning in 1861, but was returned to the original $20.67/oz. parity in 1879.

During that time, the U.S. was the most successful country in the world. Britain was the world leader, but it had an advantage of centuries; the United States rose to challenge Britain from a dead start. In 1789, most of what later became the United States was still owned by Britain, France, Spain and Mexico. Already by 1850, the United States held nearly all of what later became the Lower 48 states, a colossus matched only by the Empire of Russia and the British Empire. By 1910 the United States, although it still deferred to Britain’s global leadership role, had overshadowed its former colonial master by virtually every metric.

This, apparently, is what can happen if you take the “false path” of gold.

This would be a pretty interesting story to tell, or, in Ledbetter’s case, argue with. Instead, his book focused on a few colorful but not particularly relevant details, even then mostly missing the point in his attempts to paint a picture of folly and “obsession.”

The most rudimentary elements make no appearance. Certainly it is a little interesting that dollar spent most of the time before 1914 at a parity value of $20.67/oz., nearly unchanged from the establishment of the United States. Yet, this detail — the parity of 23.2 troy grains or $20.67/oz. — is not even mentioned. Instead, the first chapter of the book focused on the California gold rush that began in 1848.

The mining business — including oil, gas and coal — has always been a playground for adventurers, rogues and charlatans. Also, it can be a messy business, hard on workers (until recent days) and commonly with some pretty ugly environmental consequences. This is true of gold mining; it is also true of mining of copper, lead, tin, zinc and lithium; and oil, gas and coal production. The California gold rush was one of the biggest mining booms of all time. Total world gold production tripled as a result. It helped inspire many to cross the Great Plains, and made California a State, a landmark step in United States history. But, all of this didn’t have much effect on gold-as-money. Mining production has always been a small fraction of total aboveground supply. Even the peak world production year of 1855 provided only 1.3% of total aboveground gold, according to estimates from GFMS. Price statistics show that this new gold production had little effect on the value of gold. Britain, France, Germany, and all the other countries in the world whose money was based on gold (nearly all of them) felt little effect from the California mining boom. In the broader picture, it was somewhat irrelevant, as I described in greater detail in Gold: the Final Standard. In any case, gold mining has continued since governments left the gold standard in 1971. About half of all the gold ever mined, in all of human history, has been mined since 1970. Annual production today is about double what it was in 1970, and ten times higher than in 1855. Gold mining has nothing to do with gold as the basis of a monetary system.

Ledbetter tried to make a big deal out of a ship that sank in 1857, carrying quite a lot of gold from California to the East Coast. Mostly, this consisted of the holdings of individual California miners, who were also on board. $1.3 million of gold went under the waves — out of world production of $155 million in 1853, and aboveground gold supplies over fifty times larger than that. For the miners, it was a tragedy; for others, irrelevant. The outcome was roughly the same if those miners had, instead of spending weeks under the hot sun with a pickaxe, stayed at home, played cards, and died of a heart attack. “Nonetheless,” Ledbetter said:

“the incident made plain the pitfalls of what had become, in a few short years, a financial system unhealthily dependent on gold.” (p. 27) I am pretty sure a sinking ship did not make that plain. This chatter about colorful mining adventures is about all he had to say about the United States’ first 71 years on a gold standard system.

Ledbetter then continued with some twists and turns that took place in 1869 and 1873, This was a time of a floating fiat dollar — the dollar had floated since the onset of the Civil War, and did not return to its prewar gold parity until the gold standard was resumed 1879. A floating dollar is one whose value changes vs. gold, or, in the common parlance, there is a “changing price of gold.” In 1869, some financial trickery resulted in the floating fiat dollar falling quickly from $131 fiat dollars/$100 in gold coin to $160/$100, and then rebounding back toward $140/$100. Like any rapid change in currency value, this caused turmoil; but it didn’t have much to do with gold. The “price of gold” in London and Paris did not change; nor were there any meaningful economic effects. Ledbetter is describing the dangers of floating fiat currencies, and consequently, “an economy that was too easily manipulated by East Coast elites for results that harmed the rest of the country.” This could be a nice description of today’s Federal Reserve-controlled floating fiat dollar, or the big banks that have been getting busted for manipulating the foreign exchange market.

The next episode that Ledbetter focused on was the Coinage Act of 1873, which effectively moved the U.S. to gold monometallism in response to the decline in the market value of silver. (The dollar was still a floating fiat currency in 1873.) All of Europe was doing the same thing, at the same time. Unfortunately, the conflict between de facto and de jure was not entirely resolved in the U.S. until the Gold Standard Act of 1900 — silver’s role in the system became a topic of contention until then, causing quite a lot of turmoil in 1892-1896. It was a problem in U.S. management of its monetary affairs, and had little to do with gold or money based on gold. Countries that managed the transition to gold monometallism more adroitly — Britain, Germany, and the Latin Monetary Union including France, Italy, Switzerland, and several others — had no difficulties.

Ledbetter concluded: “Despite many attempted legislative fixes, the [U.S.] government in the last quarter of the nineteenth century could find no way to maintain a stable system of metal-backed currency.” (p. 56) And yet, the dollar was soundly fixed to its $20.67/oz. parity, and maintained stable exchange rates with other currencies that were also on the gold standard system.

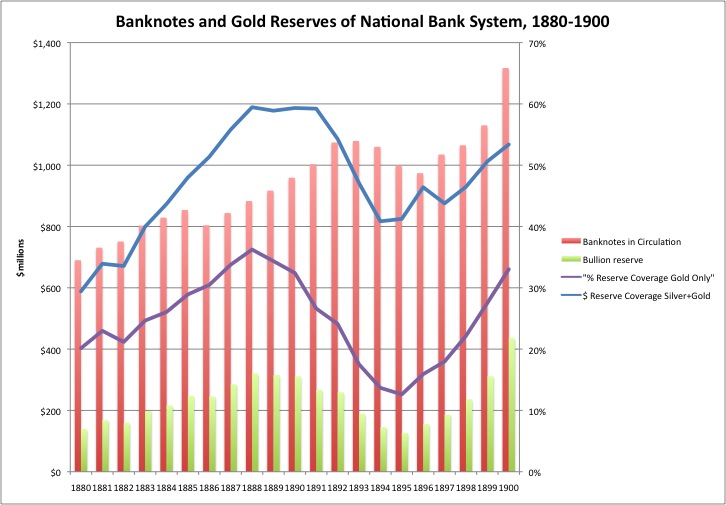

In 1893 and 1896, the U.S. had quite a lot of difficulties related to various political threats that the U.S. would effectively adopt a silver basis for the dollar, which would at first involve roughly a 50% devaluation of the dollar, followed by a floating value of the dollar vs. other gold-based currencies, depending on the market value of silver vs. gold. In effect, the U.S. would abandon the gold bloc of Britain, France, Germany and the rest of Europe, and join silver-based China. Who wouldn’t panic in the face of such risk? You would sell all kinds of U.S. dollar-based assets, and get into gold and assets based on reliably gold-liked foreign currencies. Ledbetter described the debates around “free coinage of silver” in some detail, but, rather pointedly, did not make much connection between the debates and the financial turmoil.

“As a result, the US Treasury experienced what would be a recurring problem during gold-standard periods: there was no way to keep the gold supply from migrating into private hands at home and abroad.” (p. 57) I suggest that you stop making devaluation threats. When the threats stopped — effectively, with the election of gold-friendly McKinley in 1896 — the gold flushed back in.

In any case, this was again a U.S.-centric episode. Europe was largely unaffected; the Barings Crisis of 1890 was a bigger deal across the Atlantic.

The last episode that Ledbetter focused on was the Panic of 1907. This was a “liquidity shortage crisis,” which I wrote about in Gold: the Once and Future Money. Basically, the economy tended to need more money around harvest season, when crops were sold and workers would be paid for the summer’s labor. The effect of this seasonal pattern was exacerbated by reserve requirements, which kept banks from using the resources they had; and also, limitations on banks that kept them from creating the needed currency on demand. (Commercial banks were also currency issuers in those days.) In any case, the problem of such “liquidity shortage crises” had already been solved by the Bank of England fifty years earlier, a process known as the “lender of last resort.” It had nothing to do with gold or the gold standard, of which the Bank of England was also the world’s greatest example. The Federal Reserve Act of 1913, which came directly out of the Panic of 1907, was not intended to abrogate the gold parity in any way. Ledbetter:

“Although the Panic of 1907 would, within a generation, be overshadowed by the Great Depression, it was one of the worst financial calamities in American history, by some measures worse than in 1893 (though shorter-lived). It was obvious that whatever virtues a formal gold standard might have, they were insufficient to stave off rapid economic disaster.” (p. 79) More gold-standard bashing, when the problem had nothing to do with gold.

And that brings to a close Ledbetter’s description of the United States’ first 125 years on a gold, from 1789 to 1914. During that time, following the “false path” or “yellow brick road” created the greatest economic power, the freest and wealthiest middle class, that the world had ever seen. Against this awesome success, Ledbetter brought: some colorful mining tales, a couple of minor episodes from the floating fiat dollar days of 1861-1879; a series of crises in the 1890s caused by the threat of departing from the gold standard and devaluing; and a Panic in 1907 that didn’t have much to do with the gold standard, as the Bank of England had already shown. If the gold standard of the nineteenth century had been a mistake, you would think that, by 1913, there would be some kind of evidence of a mistake; some kind of negative consequences; and that the gold standard would not be very popular. And yet, in 1913, the general consensus was that the Classical Liberal economic framework of free capitalism, low taxes and a gold standard system was a roaring success. The critics were the Socialists and Marxists; but even Marx himself was a supporter of gold-based money. It was, perhaps, the only thing in the entire Classical Liberal capitalist consensus that he agreed with.

The book as a whole has a sort of episodic quality, a quality that I have noticed also in formal economic papers by younger academics. Work of the past, the 1950s or 1960s for example, has a sort of internal consistency, like a tightly-scripted 1950s drama. The author makes a point, and then brings up some evidence in support. Even if wrong (usually), there is a sort of identifiable logic in it, an A thus B thus C quality. Recent writing is more like a Miley Cyrus music video: disconnected images without clear rational meaning, but which have a sort of emotional impact and build up a series of irrational associations. Apparently, writers don’t have to make sense anymore. Dumbed-down readers don’t notice — they are accustomed to this. Thus, we get a series of dramatic images, but whose rational significance is not clear; from this follows some assertions made largely without evidence. This, the conclusion of the Introduction, is supposedly what we are going to learn in this book:

“The naturalist writer Frank Norris depicted in his novel McTeague a bleak parable in which lust for gold ends in a Death Valley stalemate, in which a live man is handcuffed to a dead one, finally in possession of a gold stash he will never be able to spend. And an unhealthy, desperate attachment to gold’s unique qualities has caused even government officials with state-of-the-art technology to abandon common sense in a twentieth-century alchemy quest.

Whether Americans see in gold the country’s salvation or its damnation, it has always represented a struggle with modernity, a symbol of timeless strength yet an accelerant of economic progress. It also symbolizes the divisions that progress brings; between city and farm, between technology and tradition, and between haves and have-nots. Such struggles with modernity lead many nations to political extremes and civil wars. For the most part, American political institutions have been able to resist such outcomes. But our understanding of those institutions is incomplete without understanding how gold itself has shaped them, and how they continue to shape gold.” (p. 9)

Cue Miley.

We will continue with One Nation Under Gold soon.