Demand for Base Money and Interest Rates

February 20, 2011

For many years, I (and others) have been pointing out that the demand for base money is not all that stable, in fact it is highly variable. I like to use the word “chaotic.” What does “chaotic” mean? It means that it is not a matter of If-A-Then-B. If you have A, then sometimes you get B, sometimes C, sometimes D. The result is that the “steering wheel and brake pedal are disconnected.” If you turn the wheel to the right (If A), then the car doesn’t necessarily turn to the right (Then B).

November 26, 2005: The Steering Wheel and Brake Pedal are Disconnected

November 20, 2005: Does “inflation targeting” work?

This is particularly true with today’s system of targeting an overnight bank rate. This is NOT the same system as was used during the gold standard years. Yes, there was an overnight bank rate, but the mechanism of the gold standard was a value target, not an interest rate target. The value target was of course the value of the currency, pegged to gold. So, although there was of course some rate at which banks lent to each other, this was more in the nature of a regular market. When you have a value target, and adjust base money accordingly, then the steering wheel and brake pedal are connected again. It is a relationship which is not chaotic, but rather one in which certain actions (increasing or reducing base money supply) reliably lead to certain conclusions (supporting or reducing the value of the currency). This is why gold standard systems work and floating currency/interest rate targeting systems do not. This is also why you cannot use an interest rate target to operate a gold standard.

Even within the context of a floating currency, sometimes a government wants to raise or lower the value of the currency. The typical notion is that a higher short-term interest rate target will lead to a higher currency, and a lower short-term interest rate target will lead to a lower currency. This idea persists for year after year even though the evidence shows it is plainly wrong. Japan has had a minimal interest rate for decades, but the yen remains one of the world’s strongest currencies. Other countries, like Turkey, have a short-term rate of 60%+, also for decades, but experience nothing but continuous inflation. The main reason this idea persists is, in my opinion, because of denial and embarassment. If the economists and central bankers were to admit that this doesn’t work, then they would have to admit that they have no technique that works. That, in other words, they are incompetent boobs at the mercy of chaos and dumb luck. Which is, actually, the fact of the matter.

Now let’s get a little more specific. Let’s say a country wants to “support its currency” somehow, and decides to raise its interest rate target. After all, they are not going to lower the rate target, right? And leaving it the same is a lot like doing nothing. So they conclude that the right move is to raise the target. (The right move is to reduce base money supply directly, and let rates fall where they will, which might be lower not higher, but that is much too sophisticated for these dummies.) So the rate target goes up.

Then what happens?

Usually this rate hike is interpreted as an economic negative. Don’t fight the Fed. This is particularly true if the rate hike is big, like to 15% or 25% or 50%, as does happen sometimes especially to emerging market countries suffering a currency crisis. If your currency is in a crisis and the short-term interest rate goes to 20%+, don’t you think that is sort of a bad sign? Anyway, the result is often that people become rather cautious, the economy suffers, and this results in a reduction in base money demand. The currency ends up falling, not rising.

Just take a simple thought exercise. Let’s say the Fed, without any previous warning, just raised its interest rate target to 10%, from around 0% today. Imagine what would happen to the stock and bond markets. Turmoil! Now, answer this: would the dollar go up or down? Think out a little bit on the timeframe. Not just ten minutes after the Fed’s announcement, but a week later. A month later. Six months later. A year later.

Who votes for up? Who votes for down? It’s hard to say, right? In that environment of economic turmoil and panic, financial system convulsions and probably expectations of dramatic economic slowdown, the dollar might fall. On the other hand, maybe people would take it as some sort of committment to a stronger dollar by any means, and the dollar would rise. Like I said, it’s chaotic. I would vote for down myself, given the present situation. However, in a different situation, I might vote for up. Chaotic.

There’s another factor worth considering. When interest rates are high, then the opportunity cost of holding non-interest-bearing cash (base money) is high. Thus, people want to hold less of it. The demand for base money declines. However, when interest rates are low, then the opportunity cost of holding non-interest-bearing cash (base money) is low. You can hold lots of it with no negative consequences. In other words, a lower interest rate leads to more base money demand, and possibly a stronger currency as a consequence. Likewise, a higher interest rate leads to less base money demand, and possibly a declining currency.

I have been aware of this for some time, but always at a somewhat anecdotal level. John Hussman has recently quantified this relationship, and it turns out to be a tighter connection than I anticipated. Read his whole writeup here:

http://hussmanfunds.com/wmc/wmc110124.htm

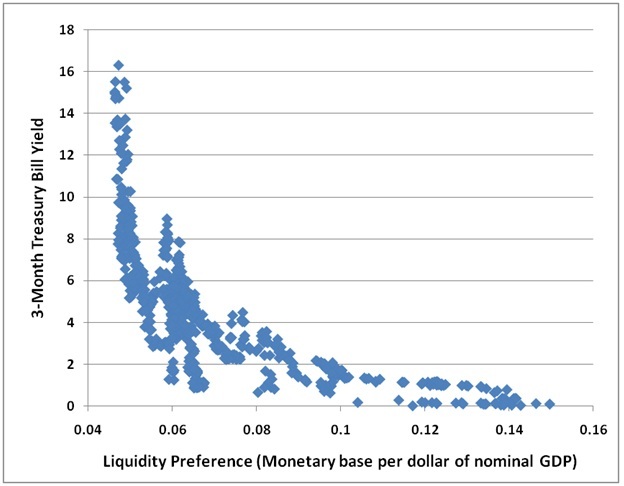

This graph is maybe a little hard to interpret at first. The bottom axis is the ratio of base money to nominal GDP, as indicated. We see that it varies from about 0.05 (i.e. 5%) to about 0.15 (15%). In other words, sometimes the total base money outstanding is 5% of GDP and other times it is 15% of GDP, a factor of 3! Also, we see that this relationship is related to short-term interest rates. From this we can get a rough guess about what might happen if the Fed went from 0% to 10%. “Liquidity preference” (demand for base money) might go from about 13% to about 5%. Which is a big move, and not necessarily currency-supportive. At all.

However, especially in the case of the U.S., the validity of this is rather hypothetical, because most base money holders are not even in the U.S.! The dollar is an international currency.

January 16, 2011: The Composition of U.S. Currency

You can see the problem of relating base money demand, which is global, with the nominal GDP of just one country. There’s so much more to it than that. Which is what I mean by “chaotic.”

That’s probably enough for today. I’m going to have more examples of these sorts of base money/”liquidity preference” things in the future. It is important to understand how economies really work, not how people would like them to work. Economies are much more variable and flexible than people imagine. All of Monetarism was based on the assumption that “velocity” (the “money”/GDP ratio) is stable. But as we can see, it is nothing remotely resembling stable. It is all over the place. This is because an “economy” consists of people. It is not some sort of ideal gas in a system of pipes. People are variable and flexible. Sometimes they want to hold shoeboxes of dollars. Sometimes they want short-term debt. Sometimes they want long-term debt. Their preferences may be rational, or they may not be. They may be driven by fads, manias, panics, whatever. Do you see what I mean by “chaotic”?