Effective Bank Recapitalization 2: Three Examples

October 12, 2008

This week, we will look at three examples of bank recapitalization using the method advocated by John Hussman, and put in practice with the FDIC’s insta-bankruptcy and sale of Washington Mutual to JP Morgan/Chase.

Newcomers may want to review my series on How Banks Work:

February 3, 2008: How Banks Work

February 10, 2008: How Banks Work 2: Shitting Like an Elephant

February 17, 2008: How Banks Work 3: More Elephant Poop

February 24, 2008: How Banks Work 4: Banks and the Economy

March 9, 2008: How Banks Work 5: Selling Loans

March 16, 2008: How Banks Work 6: Liquidity Crises and Bank Runs

March 23, 2008: How Banks Work 7: the Lender of Last Resort

October 5, 2008: Effective Bank Recapitalization

There are a number of ways of recapitalizing banks. If the problem is not too large, the government could make an investment in preferred shares, or common shares. However, especially due to the fear of potential losses from off-balance-sheet derivatives (whether or not they would actually turn into real losses), we are perhaps beyond that point now. Nobody can be sure that an institution is solvent. This method amounts to a sort of flash bankruptcy and either government receivership or a debt/equity swap, to be applied to those institutions which, due to funding issues, would otherwise go into regular bankruptcy. In other words, it performs for larger institutions much what the FDIC performs for smaller ones.

The goals are twofold:

1) Because the government is already liable for guaranteed deposits, it may as well backstop the institution, which can then support the deposits, rather than going through a liquidation.

2) The government wants to avoid “systemic issues,” related to runs on uninsured deposits and availability of working capital to non-financial entities.

We also have, as goals:

1) To avoid “socializing the losses.” These are institutions that would otherwise have gone into bankruptcy.

2) To avoid theft via government sales of assets at super-cheap prices. Also, to avoid dumping assets on distressed markets for broader systemic reasons.

First, let’s say something about bankruptcy. Bankruptcy doesn’t mean that everyone is fired and the laser printer is sold on eBay. It may get to that. All that it means is that the company is unable to fulfill an obligation (typically a payment of some kind), so then the courts get involved to see who gets paid what, and who doesn’t get paid. For example, depositors get paid, but derivatives liabilities do not. Companies can operate in bankruptcy for many years. People still show up for work, and the business continues. For example, if GM went bankrupt, that doesn’t mean the factories stop producing cars. It may mean that GM stops making payments on its debt, and comes to a new agreement with labor regarding medical expenses, but keeps selling cars. Bankruptcy is a way to eliminate old obligations and establish new ones.

The proposal here is to eliminate the junior portions of the capital structure, mostly common equity and preferred equity. These would take a loss in a bankruptcy anyway, and are very close to zero as it is, so this is no different. The next rung on the capital chain, the present non-depositor debt holders, would become the new equity holders via a debt/equity swap, which is a very common method in bankruptcy reorganization. Also, other non-deposit liabilities, notably derivatives liabilities, would be eliminated, as would be the case in a regular bankruptcy. So, nobody gets “bailed out” except the depositors, who would be bailed out anyway via the FDIC guarantee. (Non-guaranteed deposits would also be protected, but that is probably prudent at this pont.) This would leave a nice, clean, well-capitalized balance sheet. Let’s see how it works:

I. Washington Mutual

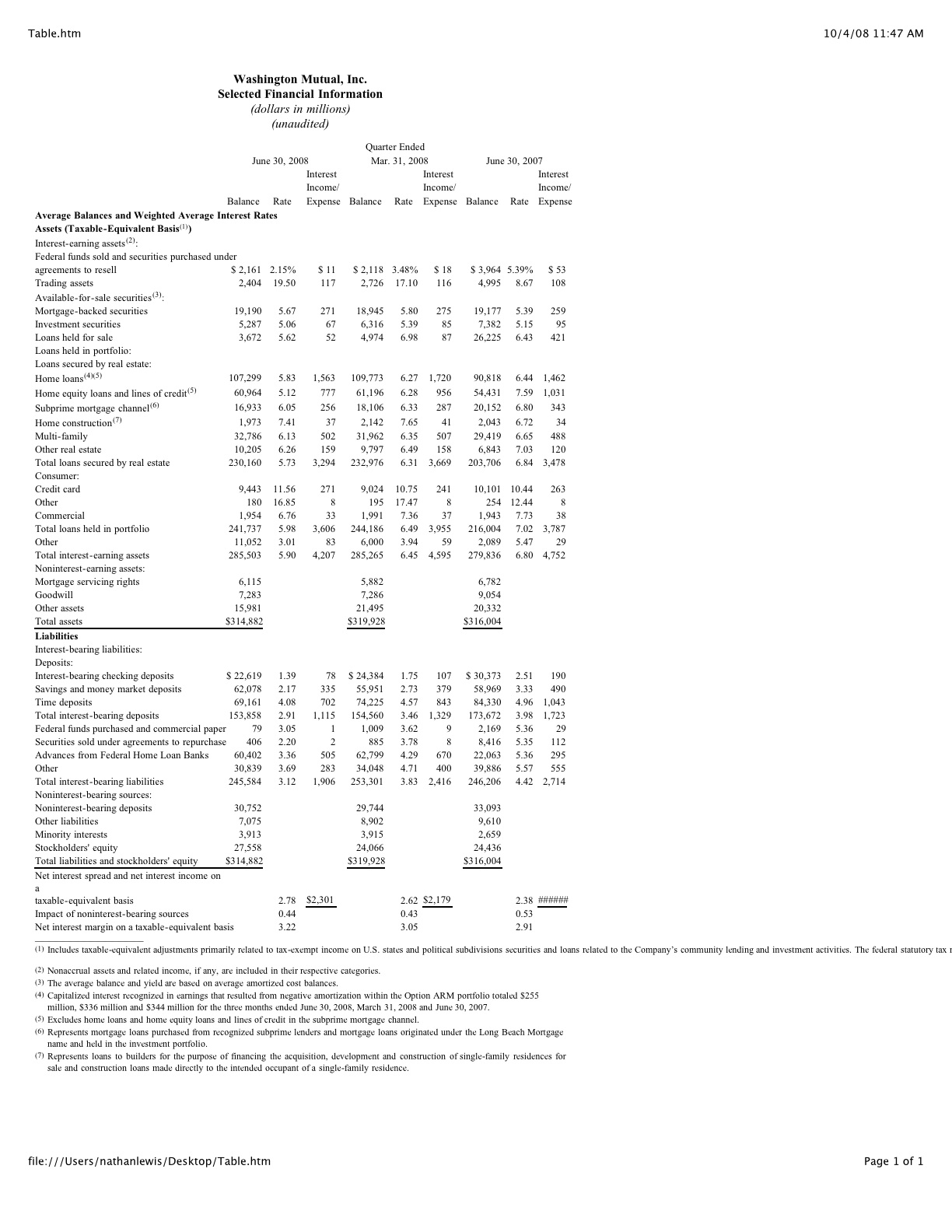

WaMu is a savings and loan, which means that it is funded almost entirely with deposits. So, there isn’t much of the capital structure besides equity to be wiped out. Here’s WaMu’s balance sheet as of June 30, 2008:

We see that the liabilities are almost all deposits. There are some advances from the FHLB, but since that is something like a government entity we might as well “guarantee” that too. That leaves minority interests and the shareholders’ equity. The “other liabilities” could be things like pensions, lease contracts, or an unpaid water cooler bill. They’re small, so let’s assume they stay too. So, an abbreviated version:

Assets: $314B

Liabilities: $283B

Shareholders’ equity and minority interests: $31B

The government recapitalizes this bank with $40 billion. This increases the assets by $40 billion, so:

Assets: $354B

Liabilities: $283B

Shareholders’ equity (the minority interests get dropped): $71B

Now, WaMu probably takes some writedowns of assets, to reflect the potential for future losses. WaMu doesn’t sell assets, it merely says “this guy owes me $1000, but I think he might not pay, so let’s put the value at $800 to reflect the risk of nonpayment.” Let’s take a $30 billion writedown. This leaves:

Assets: $324B

Liabilities: $283B

Shareholders’ equity: $41 billion

Now, the equity is 12.65% of the assets, which is a pretty cushy ratio. Also, the assets have been written down already to reflect future credit losses, so of course there is less risk of further accounting losses, because the losses have already been taken in advance. If, unfortunately, WaMu’s assets are so bad that a further writedown is needed, then it is understood that the government will provide more capital. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, all of WaMu’s off-balance sheet nasties get disappeared in the flash-bankruptcy, so we don’t have to worry about stuff that’s in a desk drawer somewhere.

Then, the government sits on WaMu for a while. WaMu can continue to make new loans, but of course they would be loans only to very good creditors, and thus not likely to cause future problems. During this time, the old, bad assets, the loans made to bad creditors, will eventually run off. They will either be repaid, or they will go into default. Either way, they come to a resolution, and disappear from the banks’ books.

During this time, WaMu is making money on its good assets. It can use these profits to offset losses from bad assets. Let’s look at their income statement:

From this, we see that WaMu had a pretax loss of $5,534m in 2Q08. However, it had provisions for loan losses of $5,913m, and losses on various securities (probably mortgage-related) of $707m. So, it appears that WaMu’s underlying profitability on its good assets was in the neighborhood of $1,086m for the quarter, or about $4,344m per year. That’s right in line with the 2Q07 pretax profit of $1,240m, before the bank started to make big losses. This $4,344m could be used to offset further losses, just as happened in 2Q08. We see here that WaMu’s assets have already been written down to a significant extent. So, any further writedowns after nationalization would be on top of that. Remember how it works: “JoeBob owes me $1000. However, JoeBob might not pay me back in full, so let’s mark his loan at $800.” This is what happened in 1H08. Then, there’s a further writedown after the nationalization. “Wow, sure are a lot of JoeBobs not paying their bills. Let’s mark the loan down to $600.” However, it turns out that this is too conservative. The collective JoeBobs actually pay back $700 out of every $1000 they were lent. So, there’s actually a latent profit here, as the loan goes from $600 on the books to $700 in real-life recoveries. Or, the collective JoeBobs really roll over and die. They only pay back $500 of every $1000 they were lent. However, the loan is already written down to $600, so the bank only has to take another $100 loss, which it can do out of its underlying profitability (of $4,344m/year).

The point is, the $30 billion in writedowns we assumed, on top of the writedowns that WaMu did previous to nationalization, plus the big capital injection of $40 billion, plus the elimination of creepy off-balance sheet liabilities, plus the promise of further government recapitalization if necessary, puts the bank in a very conservative position. A bank people can trust. This eliminates all the “systemic” issues.

After a while, perhaps a few years, but possibly less than that, WaMu is a nice, clean shiny bank with generally good assets and robust capitalization. Then, the government IPOs the bank back to the market. A clean, well run bank will typically get a price of about 2x book value, possibly as high as 3x. The book value is $40B, the amount of the recapitalization, or more, if there have been retained earnings while the government has held the company. Thus, the IPO sale price might be around $80B. That’s a profit of $40B for the government.

II. Wachovia

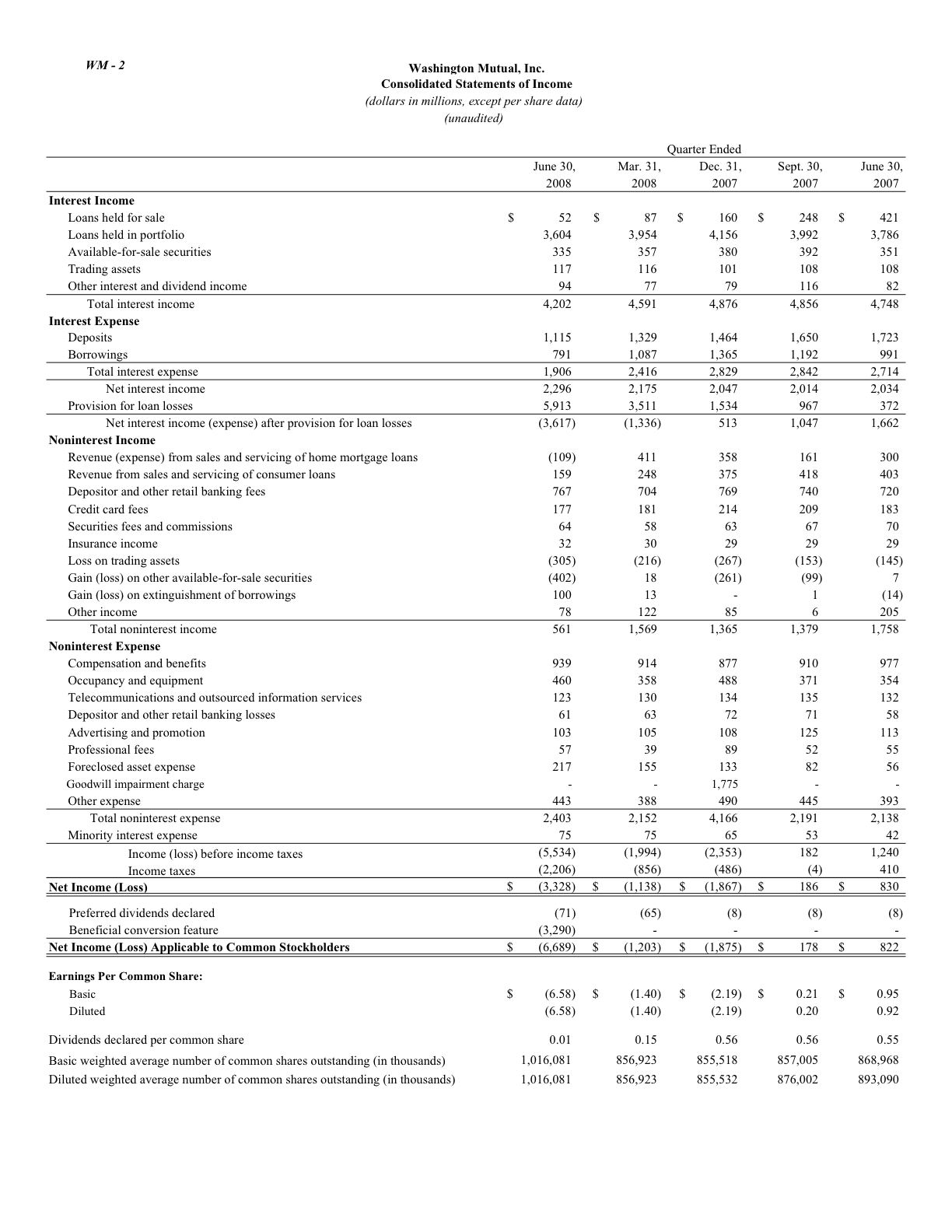

Here’s Wachovia’s 1H08 balance sheet:

Wachovia is a regular bank, as opposed to an S&L, so it’s more complicated. Deposits are only 61% of total liabilities. This gives us quite a bit more to work with. In this case, with government oversight, a debt/equity conversion could be organized. There is so much non-deposit debt (at least $55B in short-term borrowings and $184B in long-term debt) that further government recapitalization shouldn’t be necessary. The shareholders’ equity would disappear, the debt would disappear, and the new equity holders would be the old debtors. The “trading account liabilities” and “other liabilities” may stay or be eliminated in bankruptcy, depending on their nature. The new balance sheet could look something like this:

Assets: $812B

Liabilities: $448B in deposits, $20B others for a total of $468B.

Shareholders’ equity: $344B (debt/equity conversion)

That would be a very well capitalized bank indeed! Maybe, as part of the process, some things like short-term debt with maturity under 90 days can be allowed to mature regularly, to prevent market chaos. Wachovia could then take massive losses (writedowns) on its loan portfolio — things like goodwill and tax loss assets probably need to be vaporized anyway — so perhaps it would look something like this:

Assets: $712B (after $100B writedown)

Liabilities: $468B

Equity: $244B

Wachovia is a big CDS dealer. To the extent possible, CDS should be “netted,” in other words, offsetting longs and shorts canceled out against each other. Remaining CDS liabilities are toast.

Result: Wachovia goes from a weak bank to one of the best capitalized on the planet. The CDS problems go poof. The government oversees the process, to prevent “systemic” issues and protect depositors, but doesn’t invest a dime. The debt holders become the new owners.

And how about those debt holders, which got a pile of equity instead? There was $239B of short- and long-term debt. Afterwards, there is shareholders’ equity of $244B. We can give a little franchise value, which I propose is 10% of assets or $72B. So, that’s a market cap of about $316B, or 1.3x book, which is normal considering that the bank is rather overcapitalized and has a lowish ROE. And, no more CDS nasties. So, the debt holders swapped $239B of debt for $316B of equity. Not the worst thing ever.

Compare this to Wachovia’s merger with Wells Fargo:

1) Wells Fargo doesn’t bring any additional capital to the table, so the combo is just as weakly capitalized as before.

2) The CDS problems remain.

3) The result is … probably a lot like Wachovia’s acquisition of Golden West. (This is how Wachovia got into trouble in the first place.) The underlying problems — insufficient capitalization, inadequate asset writedowns, mystery CDS liabilities — remain.

III. Citigroup

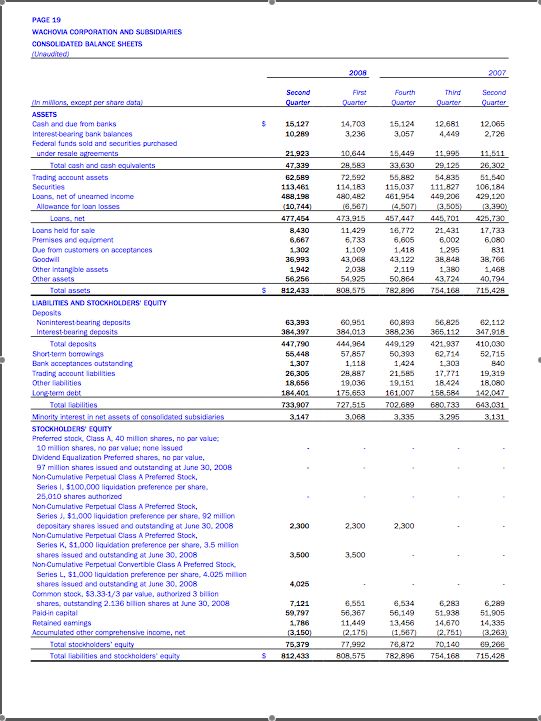

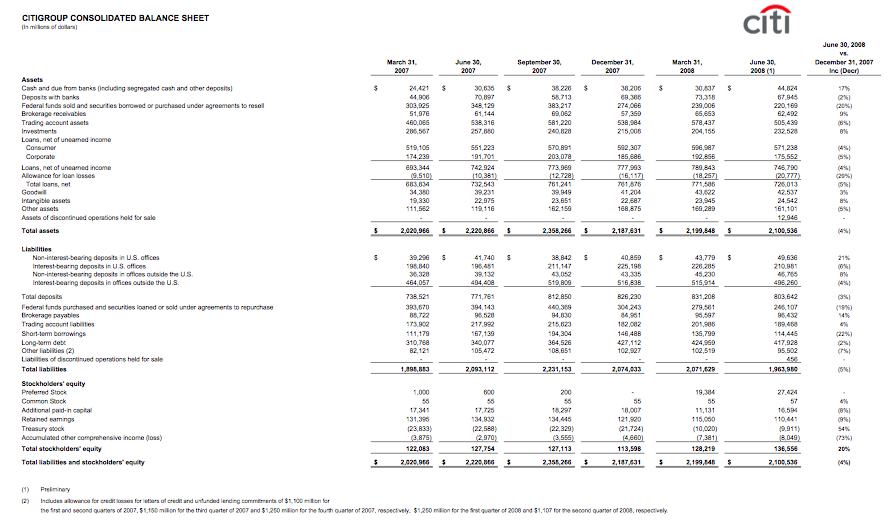

Here’s Citigroup’s balance sheet:

Here we have $114B in short-term borrowings and $420B in long-term debt. Let’s just say that the short-term debt with maturity under 90 days is allowed to mature, and the long-term borrowings are converted into equity. The Fed funds purchased will stay (not so good to stiff the Fed maybe). That would leave:

Assets: $2,100B

Liabilities: About $1400B (after debt/equity conversion, elimination of some junior liabilities)

Equity: $700B

Once again, a very well capitalized bank. Then, the bank takes a massive writedown, marking weak assets at a good estimate of their real value, so it looks something like this:

Assets: $1,800B

Liabilities: $1400B

Equity: $400B

Of course, CDS liabilities and the like are either netted or disappear into the ether.

It is probably not necessary to have quite so much equity. After a while, maybe a few years, when all the bad news has come out, the equity holders can arrange what amounts to an equity/debt swap. The bank would issue debt, and use the proceeds to buy back equity. Investment bankers and private equity guys do this sort of thing all day.

Once again, we achieve our goals:

1) A nice clean balance sheet. This means that assets are marked down to their real value, and there’s plenty of capital.

2) No off-balance sheet nasties.

3) Depositors etc. are protected, thus solving “systemic” issues.

The government, once again, serves as a facilitator. It invests nothing, but makes sure the process runs smoothly.

* * *

Now, there are some issues with this plan. The first is: there is bankruptcy everywhere. That, of course, is the point — a “flash-bankruptcy” that allows financial institutions to reorganize and heal themselves in a way that is possible only in bankruptcy. Normally, it is not such a good idea to promote mass bankruptcy. For example, holders of Wachovia or Citi debt might be quite surprised to find themselves with huge equity shareholdings. However, things have gotten to the point that bankruptcy would have resulted anyway, so we are not really causing any new problems here. If the problems weren’t so big, then the wave of private-market recapitalizations we saw in the first half would have been effective. Well, we tried that, and it didn’t work so on to the next thing.

The other problem is the CDS world. Every time there is a bankruptcy, there is an “event of default” that sets off big CDS payments. Also, at the same time, these institutions would be absolved of their CDS liabilities, these being junior in the event of bankruptcy. This will materialize the Great CDS disaster, which is: a) huge defaults, and b) counterparties are unable to pay. Well, that was going to happen anyway, so really what we are doing here is allowing all those who fooled around in the CDS world to get what was coming to them, while we resolve the “systemic” issues that could cause problems (and are causing problems today) for the rest of the economy.

When Wells Fargo bought Wachovia, for example, that avoided an event-of-default on Wachovia, so CDS on Wachovia was not set off. Many of the government’s actions can be interpreted as avoidance of where the CDS market is naturally heading. The problem is, selling Wachovia to Wells Fargo, as noted previously, doesn’t solve the problem of insufficient capital, assets that are not properly marked down, and too many black-box derivatives liabilities at financial institutions.

* * *

Holding up the mountain of shit: It is apparent that what Paulson is trying to do is to support the mountain of derivatives liabilities. My solution makes them disappear. Why do you think AIG got an $85 billion loan from the Fed, to which has now been added another $37.8 billion (an oddly precise number). Is it because of AIG’s profitable insurance division? Or, is it because of AIG’s derivatives (CDS) insurance division, which is a catastrophe? Well, that’s real hard to answer. What could have happened is:

1) AIG goes into bankruptcy and government receivership, which is basically what happened.

2) AIG’s derivatives counterparties eat shit, which is what is supposed to happen in a bankruptcy and receivership situation, but didn’t.

3) AIG’s other creditors, such as those with insurance policies, are basically fine — indeed better than fine, because they don’t have to worry about the derivatives bomb anymore.

4) The government recapitalizes (if necessary) AIG, then IPOs it back to the market — only the profitable, clean insurance division without the derivatives crap or other balance-sheet nasties.

5) The government makes a fat profit.

6) The economy is saved.

However, what would not be saved, in this scenario, are the derivatives counterparties. Well, they shouldn’t have entered agreements with entities (AIG) that are unable to pay. Because, if AIG went into bankruptcy, those derivatives claims would not be paid. Hey, AIG did go bust! So, the natural thing to happen next is that those derivatives liabilities are not paid. Probably, this would make people rather more cautious about such things in the future. That might be a good thing.

The problem here is that the Fed has already blown $122 billion down the black hole of CDS derivatives, and AIG is still not in good shape. If they had blown out the derivatives liabilities, and other off-balance sheet nasties, and maybe some of the junior portions of the capital structure, and kept the healthy insurance division, they could have recapitalized the whole thing for maybe $50 billion, and IPOed it back to the market with a big profit.

What happens next? AIG’s derivatives counterparties — wanna bet Goldman Sachs is a biggie? And JP Morgan? — take a big loss, which is exactly what they should take. Then what? If GS can’t take the hit, it goes into bankruptcy and is liquidated, just like Lehman Brothers. And what happens to the bankers? They go find a job somewhere else. Lehman’s sales and trading is now part of Barclays. Bankers change jobs all the time even during the good times. Big deal. And what happens to Goldman’s creditors? They get what they get in regular bankruptcy liquidation. That should help keep them from loaning money to entities levered 30+:1 in the future. Which might also be a good thing.

The people who take a real big hit are Goldman Sachs’ shareholders. Like the top management. Or the former top management, like Hank Paulson. I bet the general public would be real disappointed about that. Barney Frank would do the hula. Something tells me Hanky Panky probably has a few bucks stuffed in his sock drawer. He isn’t going to suffer.

As it is, AIG now has a big pile of debts. This $85+$37.8 billion business is not a free giveaway, its a loan. That just replaces the derivatives liability with a debt liability. This doesn’t bail out AIG, it bails out AIG’s derivatives counterparties — Goldman, JP, etc — who would have gotten a rotten apple otherwise, instead of $122B. And, the Fed’s loans are probably senior to other debt liabilities. AIG’s other creditors are now wondering if/when they would get paid back, as AIG now has liabilities out the wazoo, and they have been kicked into the junior position. AIG is not profitable, clean, etc. So, people don’t want to do business with AIG, thus continuing the credit crisis.

You can see why the government should be prepared for a systemic solution. Because, this sort of thing would cause a chain of bankruptcies. So, the method has to be in place to take these institutions into government receivership, clean up their balance sheets by blowing out the derivatives liabilities and junior capital elements, recapitalize them, make them clean and shiny and beautiful (ample capital, ample reserves for losses, properly marked assets and no derivatives nasties), and later sell them back to the market at a profit. I suggest that the government better go this route while it still has time and resources to do so, instead of squandering both in an effort to uphold the Mountain of Shit.

This might be their last weekend.

The ultimate losers would be those investors who are taking losses on the junior debt elements. (The equity guys have already taken their hits.) We’re talking about various investment funds that own the debt of Goldman Sachs, etc. So, they take a loss, or are converted to equity. So what. Actually, the money is already lost — it was lost when the crappy housing loans were made to people who couldn’t pay them — and what remains is the accounting of the losses.

* * *

I’ll say it again: the derivatives liabilities need to disappear for banks to be considered healthy again. In my opinion, the best way to accomplish this is with a “flash bankruptcy” as described above. Some banks might not have derivatives (CDS especially) liabilities, but who knows for sure? On Friday it appeared that there were about $400 billion of CDS liabilities related to Lehman’s bankruptcy alone. You see that the government can’t effectively recapitalize the banking system without blowing out these liabilities, because the CDS liabilities would chew up all the new capital. The choice is:

1) The government recapitalizes the banks with $400 billion. The $400 billion is immediately lost via one single bankruptcy. What about GMAC? What about Morgan Stanley? The end result: $400 billion up in smoke, and the systemic problems remain.

Let’s look at a specific example. The government invests $50 billion in Citibank, because Citibank needs capital. Citibank then loses $50 billion in CDS liabilities. End result: sqatsky.

2) The government takes an institution through a “flash bankruptcy.” Derivatives liabilities are eliminated, and junior portions of the capital structure take losses/are converted to equity. End result: the government recapitalizes an institution with $50-$100 billion, or zero even, and it is now healthy and whole. Later, the government IPOs the institution bank to the market and gets its money back, and maybe makes a profit.

What is the goal?: the goal is to produce a healthy, functioning financial entitity, via government recapitalization. “Healthy and functioning” means plenty of capital, ample loss provsions, and no nasty surprises, especially derivatives liabilities. Do it over and over (or all at once), and you have a healthy financial system.

As you can see, the difference is the difference between effective recapitalization and ineffective recapitalization. The government doesn’t have many bullets left. Once people stop buying Treasury bonds, it’s all over for everyone, as we then enter hyperinflationary collapse.

Probably, this weekend governments are going to come up with a financial sector recapitalization plan. It probably won’t work. But, it could work, if it was done correctly.

* * *

You have to admit, this stuff is complicated. That’s why — I’ll say it again — you have to understand how banks work. It’s a hard thing to learn when you are already in a crisis.

February 3, 2008: How Banks Work

February 10, 2008: How Banks Work 2: Shitting Like an Elephant

February 17, 2008: How Banks Work 3: More Elephant Poop

February 24, 2008: How Banks Work 4: Banks and the Economy

March 9, 2008: How Banks Work 5: Selling Loans

March 16, 2008: How Banks Work 6: Liquidity Crises and Bank Runs

March 23, 2008: How Banks Work 7: the Lender of Last Resort

During these periods, journalists and other generalists tend to lapse into extreme forms of “metaphor economics.” The present metaphor is the “bazooka.” Everyone wants to know, “is the bazooka big enough?” Because, if the “bazooka” is “big enough,” we can “blow away the problem,” presumably. From our discussion above, it is not really a question of bigger or smaller, but rather exactly what is done and does it address the problem. You can have a “big bazooka” that is a complete waste of time, or you can have a small and costless rule change, like Putin’s 13% flat tax or a gold standard, that radically alters the economic destiny of a nation, or the planet.

When I was in Japan, the popular “bazooka” of the time was public works spending. Once or twice a year, the government would come out with some preposterous plan to build more bridges to nowhere. People would always ask: “Is it enough?” Nobody asked: “Is it relevant?” Was the economic problem really a shortage of bridges? Or was the problem something else? Thus, a great number of bridges were built, which accomplished almost nothing except to create a new problem, namely radical government indebtedness.

That’s why I talk about Identifying the Problem.

January 27, 2008: Crisis Management

Some people, like Bill Gross of Pimco, have started to talk about large-scale public works stimulus in the U.S. I would feel bad if I had to tell them how little this accomplishes.

* * *

Debt/Equity swap: Why a debt/equity swap? This is to be fair to the debt holders. Once the equity gets wiped out, then the debt takes a loss of some sort. How much of a loss? In the case of a liquidation, this is easy to answer. In a going concern, however, it is a lot cloudier.

For example, let’s say someone bought a house for $500,000 with $100,000 down. There’s a mortgage for $400,000. The house goes into foreclosure and is sold for $350,000. The “equity holder” (owner) is completely wiped out. Then, the debt holder gets $350,000, which is less than $400,000. So, the debt holder takes a loss of $50,000. Pretty simple.

Now, let’s say you’re a bank. You have 1000 mortgages for a total of $400m. Of these, 40 mortgages are in default, and 80 are delinquent. The equity holders are effectively wiped out, because, due to poor capitalization (potential losses in excess of equity), the bank can’t continue as a going concern (nobody will lend to it) without recapitalization. So, how much of a hit does the debt take? We have no idea. What will be the recovery on the defaulted loans? How many delinquent loans will go into default? How many performing loans will become delinquent? What will be the performance of new loans that haven’t even been made yet? It will be ten years before these questions have a definitive answer. So, you can’t really say, in advance: “The debt holders need to take a 10%/50%/100% loss.”

By making the debt holders the new equity holders, the debt holders become entitled to the cashflow from the loans — whatever it happens to be — over the next ten years or in perpetuity. In short: the debt holders (now equity holders) own the loan. Literally. So, if the loan pays out $0.50, then the debt holders get $0.50. If it pays out $0.70 or $0.20, then the debt holders get that. This is how capitalism works. These sorts of situations are fairly common in a distressed debt (bankruptcy restructuring) situation.

The important role for the goverment would be to make this conversion process very quick, with no messy loose ends. It could happen overnight. Afterwards, the bank is no longer in bankruptcy. It is a normal going concern, with a new, much healthier balance sheet, and a new stock listed on the exchange. The debt holders (now equity holders) can then choose to exit via the stock market if they wish.

* * *

The Washington Post reported on Friday that the Treasury was working on a plan to take a 10%-15% stake in banks.

1) The recapitalization is totally insufficient. They need to take a 100% stake in banks (except for the strongest, like Wells Fargo wishes it was), and recapitalize them in full, as described above.

2) It appears that the banks don’t go through the flash-bankruptcy process, by which they can be recapitalized through the elimination of junior capital positions and stripped of derivatives liabilities

It won’t work.

* * *

Lehman CDS settled Friday, at $0.08625. That means, out of $400 billion of CDS, someone has to pay someone else $365 billion. $365 billion! Hahahahahaha! Do you see why these liabilities need to disappear? The $700 billion TARP facility (which can apparently be used to recapitalize banks) doesn’t mean much when banks (and other liabilities holders) can lose $365 billion on a single bankruptcy, when there will be many, many more bankruptcies to come. Thus, LIBOR remains bid-only.

Citadel and Pimco named as major liability holders. Expect mass carnage.