We commonly hear that the world gold standard of the 1920s, reconstructed after World War I, was somehow radically different than the gold standard systems prior to 1913. A meeting in Genoa in 1922 gets a lot of attention.

This serves a certain political or rhetorical purpose: first, it allows some people to claim that the gold standard systems of the 1920s, the so-called “gold exchange standard” systems, “weren’t really a gold standard,” so the gold standard was not to blame for the Great Depression. Then, ironically, these same people typically turn around and claim that the supposedly-faulty not-really-a-gold-standard systems of the 1920s actually were to blame for the Great Depression. This is quite an intellectual somersault, you have to admit.

But, a “gold exchange standard” is really not much more than a currency board. Currency boards work today, with no great problems and high reliability. So, what was the problem, exactly? Also, the value of the currencies were clearly linked to gold, by being linked to a “reserve currency” itself linked to gold. Gold was clearly the “standard of value” for these curencies.

I’ve argued that the so-called “gold exchange standard” was indeed a legitimate form of gold standard system. It worked fine, without any particular issues, and with high reliability, just as currency boards operate today. There is an issue when the reserve currency itself leaves gold, as was the case for Britain in 1914 and 1931, and the U.S. in 1971. But, except for that, the track record is pretty good.

Read Gold and the Gold Standard (1944), by Edwin Kemmerer. Lots of good info here from the guy who actually set up a lot of “gold exchange standards” among Latin American countries in the 1920s. He tells you how they work, including a detailed example from the Philippines — in 1905-1910.

The “gold exchange standard” was actually quite common in the pre-1913 era as well. In fact, all but three major countries — the U.S., Britain and France — regularly engaged in foreign exchange transactions, and held foreign exchange reserve assets, as part of their regular operating mechanisms. Often, they also had direct convertibility into gold as well, plus domestic debt assets including discounting activities, and also various forms of direct lending to governments or government bond holdings. So, there was not a clear distinction between a system that “was,” or “was not,” a gold exchange standard. An interesting example is given by Sweden. Sweden held gold bullion, and had direct convertiblity into gold. However, Sweden also held substantial foreign exchange assets, in five (!) reserve currencies. Most importantly, over 99% of the Bank of Sweden’s transactions, in terms of volume, were done in foreign exchange. Thus, in practical terms, it was 99%+ of a 100% “gold exchange standard,” even though it is not categorized as such today. Since most other central banks also held substantial amounts of foreign exchange — although perhaps not as much as Sweden — I expect that they too did most of their transactions in foreign exchange rather than in gold or in domestic assets. Thus, the 1920s period, the supposed “gold exchange standard,” was really something of an extension of what was already the norm in the pre-1913 period. The Bretton Woods period was a still further extension.

It may seem that there were “more central banks on a gold-exchange standard” in the 1920s, but this was due in part because there were more central banks. The Kemmerer Commission went around Latin America setting up new central banks in the 1920s. Also, there were a number of new countries that emerged in eastern Europe after World War I — Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and more — which also adopted “gold exchange standards,” just as peripheral countries did in the pre-1913 period as well.

The 1920s period was not qualitatively different than the pre-1913 period. It was more of a matter of degree. Both were gold standard systems.

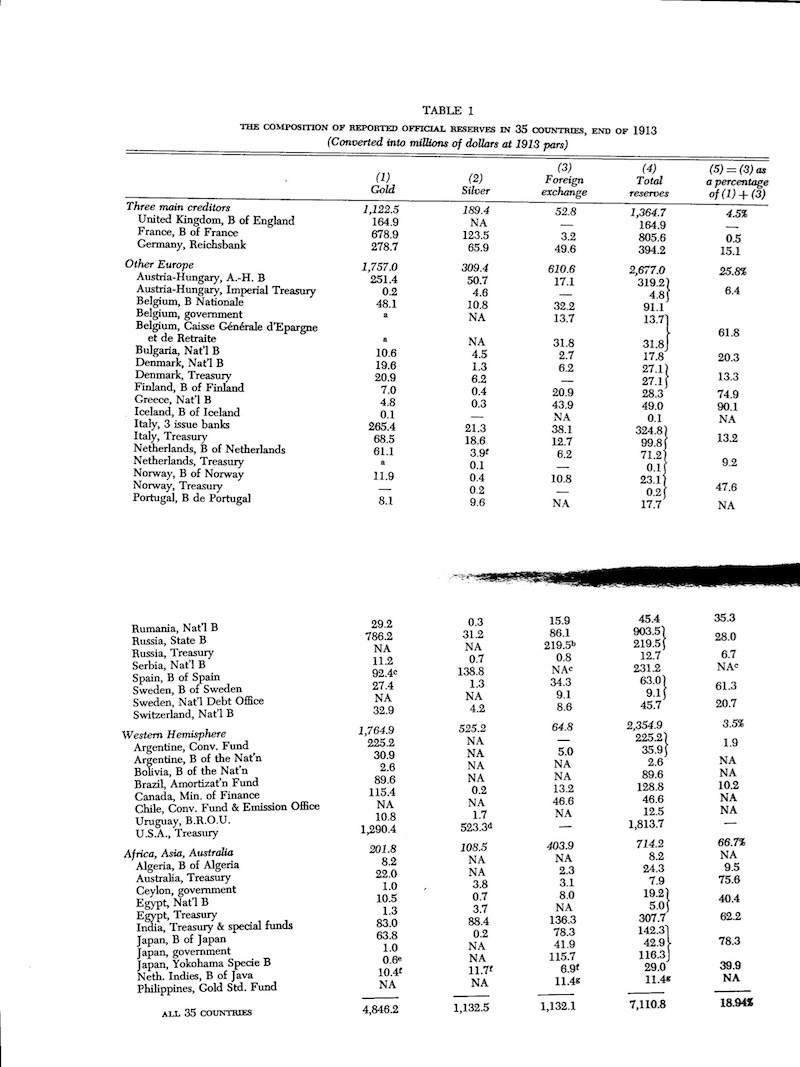

Let’s see what I mean. This table is from Key Currencies and Gold, 1900-1913 (1969), by Peter Lindert.

As you can see, most every country except for Britain, the U.S. and France, had substantial foreign reserves, and probably — like Sweden — relied on foreign exchange transactions predominantly to manage the value of their currencies, just like a currency board today.

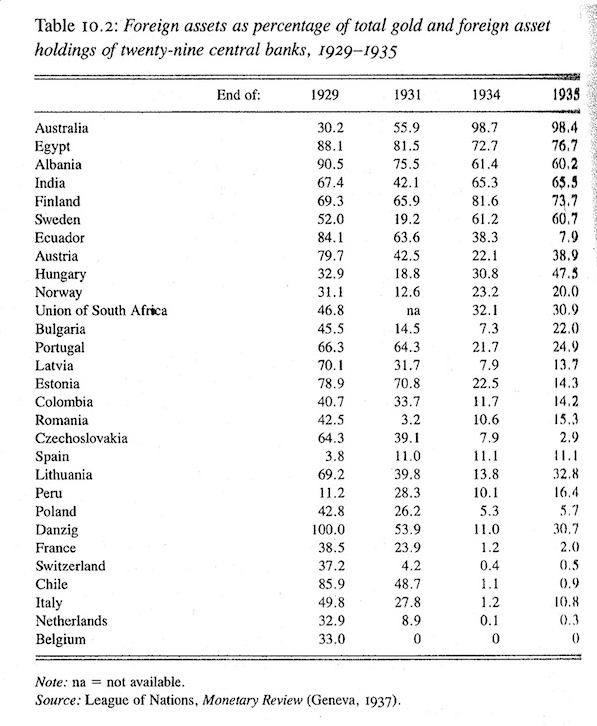

As we can see, the foreign exchange reserve ratios are higher here. But it is a matter of degree, not some wholly new arrangement. This is from Elusive Stability: Essays in the History of International Finance, by Barry Eichengreen.

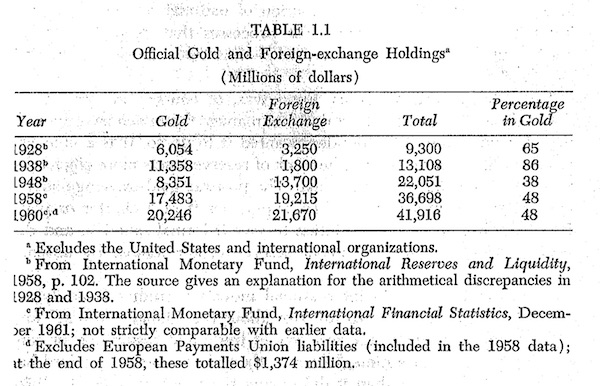

Much the same was true during the Bretton Woods era. However, by this time, direct convertibility into gold was becoming rarer.

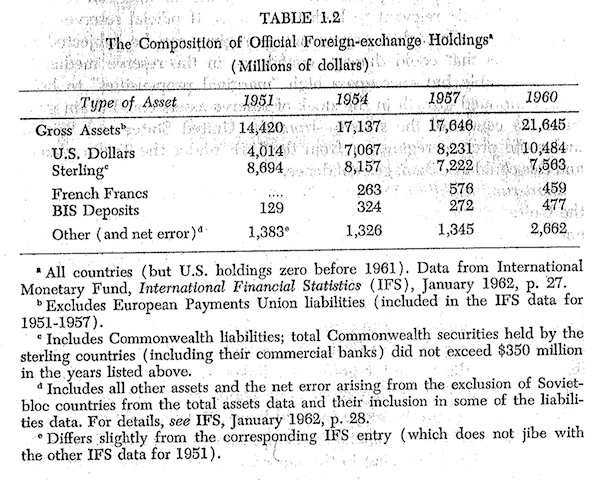

A surprising amount of foreign reserves during the Bretton Woods era were in the form of British pounds. This is from Reserve Asset Preferences of Central Banks and Stability of the Gold Exchange Standard, by Peter Kenen.

Or, as Lindert put it in 1969:

The similarity in composition of reserves between the last prewar years and the mid-1920s tends to undermine the frequent distinction between a “nineteenth century (prewar) gold standard” and a “gold-exchange standard” of the interwar and postwar eras. The periodization of the history of international finance involved in such a semantic choice can obscure the continuity of the emergence of a key-currency system.

More important than the composition of reserves, in my opinion, was the volume of transactions conducted via foreign exchange. This data is hard to come by, but the Swedish example suggests that it was rather high indeed.