Gold Standard Technical Operating Discussions 2: More Variations

January 15, 2012

Last week, we were talking about some of the technical issues of operating a gold standard system. There are actually quite a few different ways you can do things.

January 8, 2012: Some Gold Standand Technical Operating Discussions

We looked at a few options: one was a standard currency board with another currency. The second was a “100% reserve” type gold standard system. The third was a gold standard system with a partial bullion reserve, and using domestic high-quality bonds (government bonds) as a reserve asset.

Our fourth example will be the operation of a gold standard system without redeemability. No gold bullion is held, only government bonds. (Actually, you can hold gold bullion as a reserve asset even without redeemability.)

All of these systems have a target — to maintain the value of their currency at a certain parity with something else, namely another currency or gold bullion — and each has a mechanism of operation based on increasing and decreasing the supply of base money. There is no interest rate policy. The question is: how, when, and how much do you increase or decrease the supply of base money? In both the currency board and gold redeemability systems, the initiator of action is some private market participant coming to the monetary authority wishing to trade the currency for another currency or gold at the specified parity price. Thus, both the timing and the size of the transaction, and corresponding adjustment in the monetary base, comes from the private market participant.

However, if we don’t have a redeemability element (either the target currency, in the case of a currency board, or gold bullion, in the case of a gold standard system), then we must have some other means of determining the timing and size of such adjustments.

For this, we can use the free market trading ratio of the currency and the target, for example, the currency and gold bullion, aka the “price of gold.” Let’s say we have a policy of maintaining the value of a currency at $1000 per ounce of gold. In other words, we want the currency to maintain a constant value of 1/1000th of an ounce of gold. Let’s say that, for whatever reason, there are more people that want to sell the currency and buy gold (at the parity price of $1000/oz.) than there are people who want to sell gold and buy the currency. The value of the currency would naturally sag a bit, until the market cleared. Thus, instead of being worth exactly 1/1000th of an oz., it might have a market value of 1/1005th of an ounce. The “price of gold” would be $1005.

At this point, the currency manager would act to reduce the supply of base money in existence. They would sell assets, presumably bonds (although it could be any asset, including gold bullion), receive money in return, and extinguish the money. The total base money in existence would shrink.

Exactly when would the currency manager act? At $1005/oz.? At $1010 oz? $1020? You could formalize this. You could say that the currency manager would not act until the value of the currency deviated from its target by at least 1%. In other words, either $1010 (reduce base money) or $990 (increase base money).

Now we have defined some operating procedures. We have a HOW (sales and purchases of bonds), a WHEN (at +-1% from the parity target), but we still need a HOW MUCH.

In what quantity should the currency manager buy or sell assets (bonds), thus altering the monetary base by an equivalent amount? You could make some rules for this too, I suppose. Maybe you can say that, for every day that the currency deviates by its target by 1% or more in value, the supply of base money is adjusted by 1% in quantity. Or, you could set up a ladder of increasing activity. For example, if the currency drops 0.5% from parity, reduce the monetary base by 1%. If this is not sufficient and the currency continues to lose value, then at 1.0% from parity, reduce it by an additional 2%. At 1.5%, reduce it by an additional 3%, and at 2.0%, reduce it by an additional 4%, for a cumulative 10%, which is actually quite a lot.

So, you could make a lot of defined rules of this sort. Historically, such rules were not laid out but rather left to the discretion of the currency manager (central bank or commercial bank), who probably has a feel for what would be appropriate.

The problem with offering discretion to the currency managers is that they might be incompetent, as most central bankers are today. They may not know what is appropriate action, and in fact they might do exactly the wrong thing! Or, they might have some sort of nefarious plan, doing the wrong thing on purpose. That happens too, you know.

Although gold standard systems in the past have almost always had a redeemability element, people who understood these things also knew that this redeemability element was not strictly necessary.

It will be seen that it is not necessary that paper money should be payable in specie to secure its value; it is only necessary that its quantity should be regulated [adjusted] according to the value of the metal which is declared to be the standard.”

David Ricardo, Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, 1817.

“If, therefore, the issue of inconvertible paper were subjected to strict rules, one rule being that whenever bullion rose above the Mint price [gold parity], the issues should be contracted until the market price of bullion and the Mint price were again in accordance, such a currency would not be subject to any of the evils usually deemed inherent in an inconvertible paper.”

John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy, 1848.

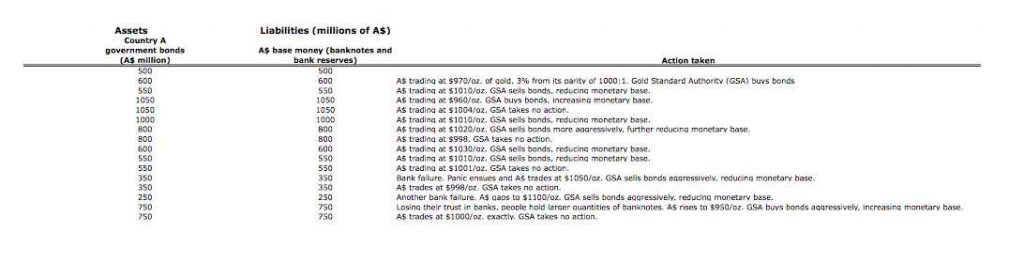

It would look something like this:

Maybe someone would say: what if people keep selling? What if the currency keeps falling in value, even though the Gold Standard Authority (GSA) is reducing the supply of money by selling assets? This would indicate that the demand for money is shrinking even faster than the monetary authority is reducing the supply. Nothing wrong with that. Just keep selling assets, more aggressively if necessary, and reducing the monetary base. Eventually, the monetary base would go to zero, and the currency would no longer exist! It would be impossible to sell more, because there’s nothing left in existence to sell.

“But,” people then say, “what about bank deposits, bonds and so forth? The total quantity of those things vastly exceeds your reserves.” As I’ve explained extensively, these things are not money. They are credit contracts, between two counterparties, a borrower and a lender.

December 1, 2011: What is Money?

A credit contract is a commitment by the borrower (not the GSA!) to deliver money (base money) at certain times and upon certain conditions. Thus, if the borrower has to deliver money, to avoid default, then obviously the borrower has a demand for money. The borrower must acquire that money in some way. If they don’t, for whatever reason, that is a credit default. It has nothing to do with the currency itself, and is not the responsibility of the currency manager.

This is a rather important point. Do you see why it I insisted that you understand what money actually is? These are not just arcane and meaningless discussions.

Now we come to a fifth example, which is something of a hybrid between the third example (gold redeemability with reserve assets including both gold bullion and bonds) and the fourth example (management of the monetary base via bond transactions, without gold redeemability).

In this example, for HOW we have two things: 1) gold redeemability, initiated by a private market participant; and 2) asset purchases and sales, initiated by the GSA in reaction to the market value of the currency compared to its parity value.

For WHEN, we have two things: 1) redeemability initiated by a private market participant; and 2) asset purchases and sales initiated by the GSA, either by discretion (in reaction to market values compared to parity) or determined by some formalized system such as the ones described earlier.

For HOW MUCH, we have two things: 1) redeemability in a quantity determined by a private market participant; and 2) asset purchases and sales initiated by the GSA (in reaction to market values compared to parity) in a quantity determined by GSA discretion or as determined by some formalized system such as the ones described earlier.

This hybrid system is, actually, the system most commonly in use in Britain and the U.S. during the 19th Century. It could be used on a monopoly basis, in the case of the Bank of England, or by many private commercial banks each issuing their own gold-linked currency, as was the case in the United States.

Because buying and selling gold bullion was somewhat cumbersome — you have to move the stuff around — gold redeemability was the less common (although perhaps more important) operating procedure. The most common was adjustments in the monetary base by way of discretionary purchases and sales of debt assets by the GSA.

Note that “debt assets” could include loans as well. Both the Bank of England and the U.S. commercial banks were also regular lenders. Thus, one way to reduce the monetary base would be to receive money in payment of interest or principal, as happens every day with a commercial bank, and take the money received and make it disappear, thus shrinking the monetary base. The bank’s assets would shrink, just as if it had sold government bonds. One way to increase the monetary base would be to make new loans, using “freshly printed money,” which would increase the monetary base and also the bank’s assets. The activities of currency management and the activities of regular commercial banking were often intertwined. Does this make things confusing? Oh, yes. That’s why there has been a long effort to separate the two actions. This happened with the Bank of England in 1844, in which the Bank’s activities were separated into an Issue Department (for the currency) and a Banking Department (for regular lending). In the U.S., responsibility for the currency was ultimately taken from regular commercial banks, mostly during the 1920s, and concentrated in the Federal Reserve. This is why our money today says “Federal Reserve Notes.”

The activities of currency management and commercial banking have been separate for quite a while now. But, you can see where we get these stories about how “banks create money and then loan it to you.” That is, indeed, what they did in the old days, to some extent. Not all loans were done this way, but some were. The funny thing is how these things keep going for generation after generation, long after they have become obsolete. It just goes to show you how many people are actually thinking about these things (0.01%) , and how many people (99.99%) are just repeating something they heard somewhere.

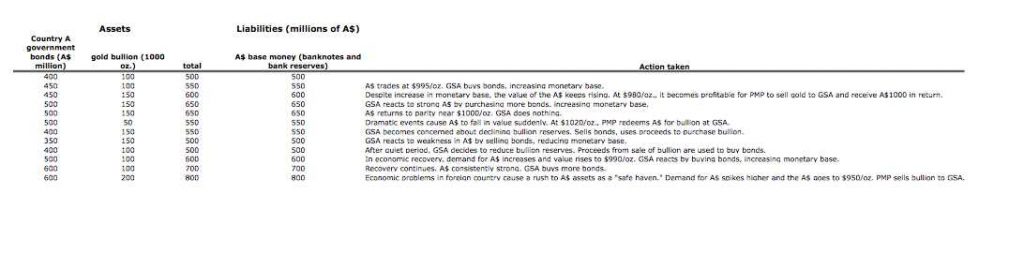

So, as an example of a hybrid system, we could have gold redeemability at +-2% from the parity value. For example, you could have a parity of $1000/oz. The GSA would sell gold at $1020/oz. — in other words, when the value of the A$ is sagging, and is 2% below its parity, such that it now takes $1020 to buy an ounce of gold instead of the promised $1000, the GSA would sell you the gold, buy the A$, and make the A$ received in the sale disappear, thus shrinking the monetary base.

At $980/oz., the GSA would buy gold, and give you A$ in return. These A$ would be “freshly printed,” and thus the purchase of gold would increase the monetary base.

In practice, transport of gold has a small cost. Let’s just say it is 1%. In other words, it costs the private market buyer or seller 1% in expenses to move the gold to and from the GSA’s vaults to their own vaults. So, even if the GSA promises to buy and sell gold at exactly $1000/oz., in practice the private market participant wouldn’t buy until the market value of the A$ drops to $1010 or beyond, at which point it becomes profitable to buy gold from the GSA. On the other side, the private market participant would sell the GSA gold when the market value of the A$ was $990/oz. Thus, even if there is not a formalized buy/sell spread or “trading band,” the difficulties of moving gold creates one naturally.

Personally, instead of having a buy/sell spread, I like to use a “redeemption fee” or “monetization fee.” In other words, the GSA will buy or sell gold at exactly $1000/oz., but, if you want to go to the GSA to buy or sell your gold instead of a private market buyer/seller, you have to pay a little fee for the privilege. The GSA might sell gold at $1000/oz. and then charge a $20/oz. (2%) “redemption fee.” This is exactly the same as selling for $1020 without a fee, but I think it helps cement the idea that the government’s parity for the A$ is exactly $1000/oz., not $980/$1020.

Within our hybrid system, we now also add purchases and sales of assets (bonds) by the GSA, to adjust the monetary base. For example, if the A$ was trading at $1005/oz. one day, i.e. a little weak but not yet at the $1020/oz. gold bullion redeemability point, the GSA would sell bonds, take A$ in return, and thus shrink the monetary base. This would support the value of the A$ and perhaps move it back to its $1000/oz. parity value. If the GSA constantly reacted to these smaller movements with such actions, theoretically the value of the A$ would never get to the point at which private market participants would go to the GSA and demand bullion in return.

Likewise, if the A$ was trading at $995/oz. one day, the GSA would buy bonds and pay for their purchase in “freshly printed” money, thus increasing the monetary base and consequently lowering the value of the A$. The value of the A$ should never get to the point where people are taking gold to the GSA to get A$ in return.

As noted before, these smaller adjustments by the GSA could be done either on a discretionary basis, or perhaps formalized in some way. In the past, they were generally discretionary.

It would look something like this:

That’s enough for this week. Actually, I haven’t got to the original topic I wanted to talk about yet. Eventually!