Life Without Cars 2014

December 28, 2014

Once a year, we take a little time to imagine Life Without Cars. Many people live without cars today, and also without bicycles (at least for daily transport use), mostly in urban areas with good public transportation. In the developing world also, most people don’t own cars, and live in urban areas with good public transportation. Before 1900, nobody used cars.

December 8, 2013: Life Without Cars: 2013 Edition

December 27, 2012: Life Without Cars: 2012 Edition

December 25, 2011: Life Without Cars: 2011 Edition

December 19, 2010: Life Without Cars: 2010 Edition

December 13, 2009: Life Without Cars: 2009 Edition

December 21, 2008: Life Without Cars

Unfortunately, when people imagine Life Without Cars today, they usually imagine today’s Suburban Hell, perhaps with some bike lanes. This is stupid. Suburban Hell is designed around automobile dependency, which is why even cyclists feel like lonely refugees in a barren landscape of gigantic roadways and parking lots. This pattern is typified by places like Phoenix, AZ, although almost all of the U.S. today is in one or another variety of Suburban Hell.

March 7, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to Suburban Hell

July 26, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 3: How the Suburbs Came to Be

July 19, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 2: Downtown

July 12, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village

You can live without a car in a place like this if you are a single male aged 18-26 with certain romantic enviro-notions, and even then only for a little while. Or, if you have a low income and just have to make do any way you can.

The primary alternative to Suburban Hell in the U.S. is what I call 19th Century Hypertrophism. This is the typical pattern of large cities from before 1940, and is typified by places like central New York and Chicago. As these environments date from the 19th century, well before the Age of Automobiles, they are often quite “walkable”, have good public transportation, many excellent examples of 19th century architecture, and particularly for New York, have many people who live there without cars. The problem of these places is that, although they have many desirable attributes from a utilitarian standpoint, they are typically rather ugly, difficult and unpleasant places to live, especially for families with young children, women, elderly, and most anyone who is not a male aged 18-30.

February 21, 2010: Toledo, Spain or Toledo, Ohio?

January 31, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York 2: The Bad and the Ugly

January 24, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York City

The main reason for the failure of 19th Century Hypertrophism is that virtually all outdoor places are “hypertrophic” and dominated by automobile traffic, mostly in the form of a very wide street with a central roadway section. In terms of living environments, this is about as good as it gets:

These better examples of 19th Century Hypertrophism also tend to be very expensive, so you can’t actually live there. You might live in a place more like this:

“Dense”? Dense enough. “Walkable”? Yes. Efficient use of space? Close enough. Public transportation? Plenty. You don’t even need a bike. It’s even rather enviro-friendly, as apartment-dwelling carless New Yorkers are far less consumptive of natural resources than their suburban counterparts.

Ugly as anything? You betcha. Millions of people commute hideous distances from the suburbs so they don’t have to live in places like this.

February 21, 2010: Toledo, Spain or Toledo, Ohio?

January 31, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York 2: The Bad and the Ugly

January 24, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York City

Just imagine pushing a stroller down the sidewalk in a place like this, or letting your five-year-olds out to play. Kinda makes you want that suburban yard, doesn’t it? The bigger the better! And so millions of people mortgage themselves up to the eyeballs to live in Suburban Hell with as big a yard as possible.

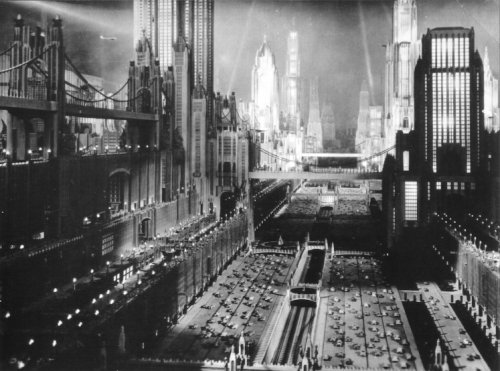

Oddly enough, 19th Century Hypertrophism is often at its best at its most hypertrophic, with the addition of 20th century high-rise architecture on the 19th century grid pattern. Like this:

However, despite some attractions, this pattern too can be a harsh and unforgiving place, especially for families with young children, which is to say, most everyone aged 0-15 and 30-50. The reality of “concrete canyons” filled with the unceasing roar of automobile traffic can be exciting at first, but ultimately wearying even to young men, and certainly even for older men and women who might not have young kids.

We have thousands and thousands of examples of 19th Century Hypertrophism in the United States, most of them built before automobiles became common in the 1920s. If this was a successful pattern, don’t you think we would have noticed it by now?

Is this your ideal of Life Without Cars? If it is so ideal, what real-life city in the U.S. exemplifies the “ideal city”?

Pretty tough to name even one, isn’t it?

The failure of 19th Century Hypertrophism can be summed up as the failure to make pleasant Places for People.

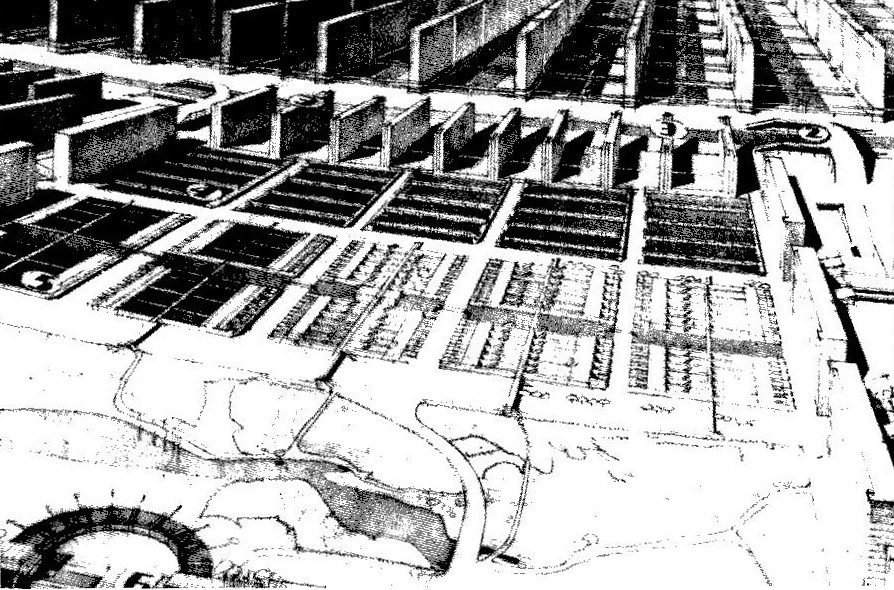

The failure of 19th Century Hypertrophism led to what I call 20th Century Hypertrophism. This was enabled by steel-framed high-rise architecture, a new development in the early 20th century. Although this is no longer very popular in the U.S. today, after many failures in the 1950s and 1960s, it has become very common elsewhere in the world.

“Towers in a park” circa 1960 (lower left corner)

20th century hypertrophism circa 2005: Dubai.

1928.

1930.

2010. Dubai.

Shanghai. Note cookie-cutter “tower in a park” residential pattern.

Although people still build this stuff today, it is not very popular in the U.S. This is basically a combination of highrises with a suburban pattern, of gigantic roadways and “green space,” this buffer vegetation everywhere which is not a park or other useful or pleasant place that people can use. It’s the same kind of buffer vegetation we see today in every suburban U.S. strip mall and office park. Because, once you have eight to twelve lanes of roaring traffic, you want a buffer, right? The result is that, once you step out of the highrise, you are in a desert of landscape greenery, parking lots and giant roadways. Not a Pleasant Place for People, no no no. Look at that photo of highrise apartments in Dubai. Is that where you would want to raise a family? What an alienating wasteland.

August 10, 2008: Visions of Future Cities

July 20, 2008: The Traditional City vs. the “Radiant City”

October 10, 2009: Place and Non-Place

You can kind of see how people thought this was a good idea. The best parts of 19th Century Hypertrophism (New York) were places like Manhattan, where the original 19th century buildings were eventually replaced by highrises. However, Manhattan is a horrible place to drive. People like Robert Moses bulldozed neighborhood after neighborhood trying to bring superhighways to New York City. However, this was a kludge at best. How much better just to design a big superhighway in the middle from scratch! The other problem of 19th Century Hypertrophism was not really the buildings themselves, which are often either rather nice 19th century buildings or 20th century highrises. The problem was when you stepped out of the building, into this noisy mess dominated by the roar of traffic. So we again adopt the Suburban ideal, of the yard/buffer around the house. However, instead of a real park, this typically degenerated into a landscaping buffer, which is not the kind of place you would want your kids to play. Once you have a lot of landscaping buffers and giant roadways, you can’t really walk anywhere anymore, so you either have to take a train or take a car.

Is this your vision of Life Without Cars? The one with a superhighway in the middle, and highrises surrounded by landscaping buffers and roadways, hardly any different than Suburban Hell?

Now we have three patterns of failure: Suburban Hell, 19th Century Hypertrophism, and 20th Century Hypertrophism. We’ve spent decades, and hundreds and hundreds of attempts all over the world, to make one of these patterns work and I would say that there is not one example in the world of a Pleasant Place for People resulting. I know that a hundred architects and urban design geeks would claim I’m wrong, but name just one real-world example of success. Because, if there was even just one example, then other people would imitate it, and there would eventually be hundreds of examples, and we would no longer hate the places we live.

So you see, just riding a bicycle, train or bus in one of these failed environments doesn’t really accomplish anything. We spent a century riding around the 19th Century Hypertrophic City in the U.S. without cars, and it was so great that, once Henry Ford made the automobile affordable in the 1920s, everybody escaped to the country as fast as they could build houses in former farmland.

What is the alternative? It is something I call the Traditional City. Although the form is as old as civilization itself, over 5000 years old, it can take many contemporary variants as is common particularly in Asia. I’ve written a lot about it elsewhere, so today, we will just take a trip to some real-world urban places where you can live happily ever after, with a family, for the entirety of your life from birth to old age, without a car. You could even combine Traditional City elements with highrise architecture, creating a hybrid where you can step out of your 60-story apartment building into a beautiful Place for People, not a 19th Century Hypertrophism or 20th Century Hypertrophism disaster.

June 17, 2007: Recipe for Florence

September 23, 2012: Corbusier Nouveau 3: Really Narrow Streets With High-Rises

August 26, 2012: Corbusier Nouveau 2: More Place and Less Non-Place

August 19, 2012: Corbusier Nouveau

That’s a long enough intro, so now sit back and enjoy your walking tour of some Traditional City environments.

This tour is of Tsumago village, in the Kiso valley of Japan. This sort of thing is common throughout Asia, with cultural differences of course.

I decided to begin here with a historical example. However, throughout all of these examples to follow, we have a certain pattern. That is: what I have been calling a “Narrow Street for People.” This is a street typically 12-20 feet wide, that is one flat surface from one side to the other, without segregation into a central roadway for wheeled vehicles and sidewalks. In effect, the whole street becomes a “sidewalk.” Motor vehicles are usually not prohibited, and the shops and so forth get deliveries, trash pickup and so forth from trucks. But, the environment is dominated by people, typically walking right in the middle of the street. They often get along just fine with motor vehicles, which must travel very slowly.

The second element is that, whether the buildings are actually attached or detached, they typically have little to no front or side setbacks. They don’t need this, because there is little to no motor traffic that they need to create a “buffer” from. However, the buildings often have rear and side yards, courtyards, and other forms of private outdoor space.

I think you will find that, whether we are looking at a historical or contemporary example, and whether in Europe, Asia, or parts of Latin America, these basic ingredients are always present.

I don’t suggest that all streets be in this format. Typically, you would have an “Arterial” street nearby, with a wide central roadway for vehicle traffic. So, there is typically no place that is more than a quarter-mile or so from an Arterial. Thus, the difficulty of driving on the Narrow Streets for People is not much of an issue, because you would only have to drive there for a quater mile or less. However, in practice, only about 20% of the streets (by length) would be Arterial or larger (“Grand Boulevard”), so 80% or so of the streets would be these Narrow Streets for People.

Notice how, even if you have never been to Japan or maybe anywhere in Asia, you are immediately comfortable and familiar with this basic urban format.

This tour of the Daikanyama district of Tokyo gives you an idea of how Traditional City design can be incorporated in a contemporary fashion not only in an antique village, but a giant metropolis. Try to find a place like this in any 19th Century Hypertrophic city in the United States. As you can see in the video, there are also large Arterials nearby, of course filled with auto traffic. However, then you take a right turn and you are back in a place that is essentially carfree. Daikanyama is only a short walk from Shibuya Station, one of central Tokyo’s major commercial areas. This is not a “suburb” or “out in the country.”

This is an extraordinary neighborhood just outside of Shinjuku Station in Tokyo, the busiest train station in the world. Yes, these are outdoor “streets,” possibly covered.

This walking tour of Dubrovnik, Croatia shows one of the hundreds of awesome Traditional City places in Europe.

This walk around Mykonos, Greece, is another example of a great Traditional City environment that is beloved by travelers. Notice that it is not that much different than the rural historic village of Tsumago, and not that much different than Daikanyama, in central Tokyo. The Traditional City form is similar everywhere.

Can you build a place like this in, for example, San Diego? Of course you can. It is just a combination of Narrow Streets for People and buildings side-by-side with no setbacks. Use whatever architectural style appeals to you. Imagine how much more popular (and profitable) that would be, as a travel destination, than just about every other warm/beachy destination in the entire United States.

Notice how you are immediately familiar and comfortable with an environment like this, even though there might not be one single place like this in a 500-mile radius from where you live.

This is a walking tour of Lyon, France.

Here’s another contemporary example. Beijing, China.

Get it? It’s so simple.

Click Here for the Traditional City/Heroic Materialism Archive