A lot of confusion stems from the differences between “prices” (or “purchasing power”) and value. I am not going to go into this in great detail now, because it can get to be a big topic. There’s a discussion in Gold: the Once and Future Money. The gist of the matter is that the value of the currency is more or less what you see in the foreign exchange market. These are relative values — values of currencies going up and down against other currencies that are also going up and down. But, nevertheless, we can at least see that there is a value, because we can indeed generate a foreign exchange trading ratio, i.e. a relative value; and this value does not correspond with changes in the CPI or “purchasing power”, except over the long term.

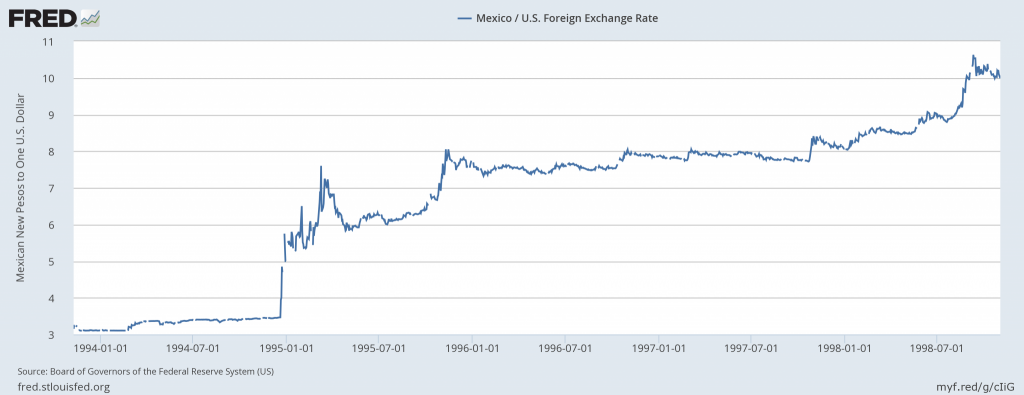

It is a little easier if we compare something that is vaguely stable and something that clearly undergoes a big change — for example, the U.S. dollar and Mexican peso, in the peso devaluation of 1995. Nobody is going to argue that “the peso didn’t really go down, the dollar went up!” Clearly, the peso went down, even if there was a little variation in the dollar as well. This change in the peso’s value, as expressed by its exchange ratio with the dollar, is what I mean by “value.” This is not a new concept: David Ricardo and others of his era (1800-1820) talked about it in great detail, because people didn’t understand it then either.

What are the characteristics of a Consumer Price Index, under an idealized regime of stable value? Too many people assume that the CPI would itself be something like perfectly flat, or “no inflation,” but this is not the case.

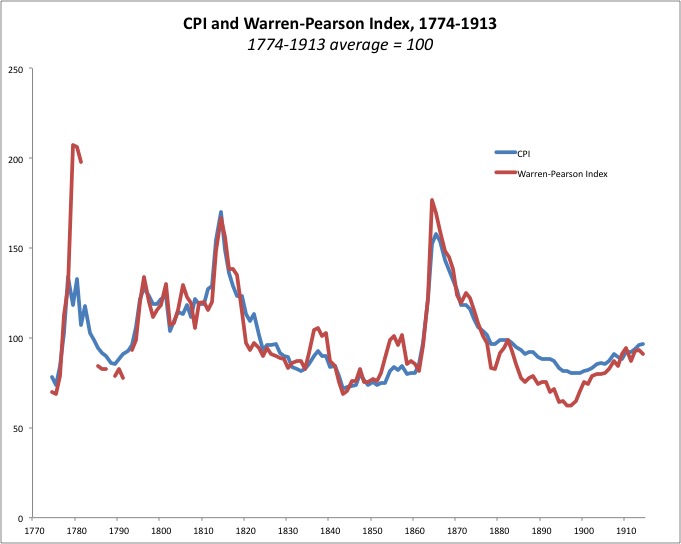

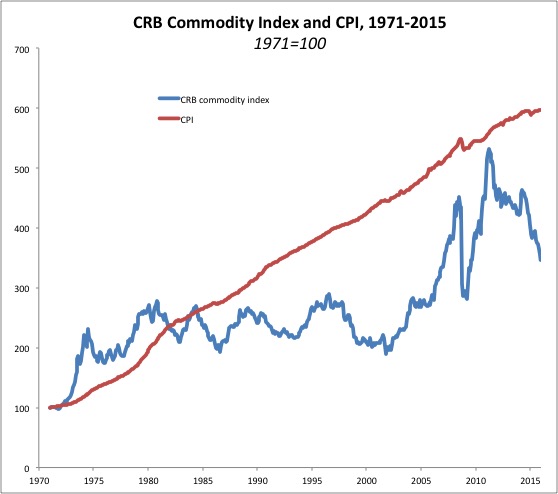

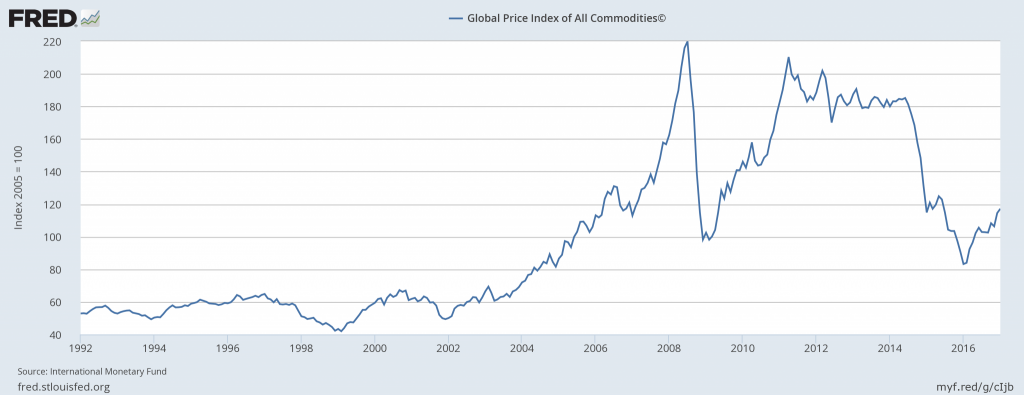

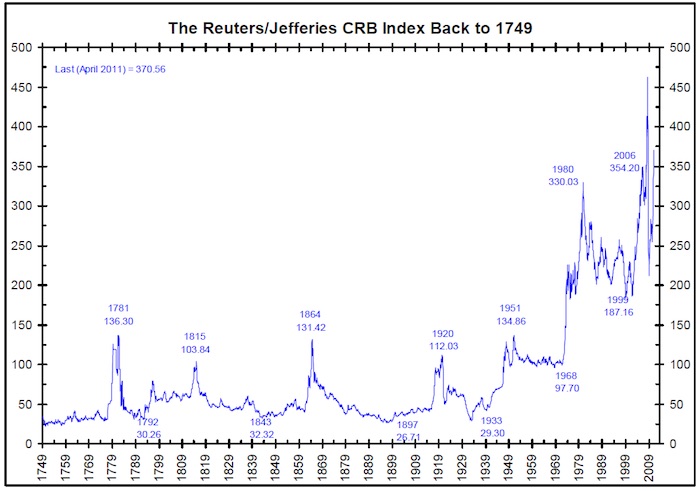

First of all, the CPI is a government statistic, one whose characteristics have been in constant flux, and one that has undergone endless modification to produce the “right” answer. Early CPI-like efforts, basically before 1940 or so, have tended to be quite a lot like raw commodity indices. We saw this in our earlier comparison between a supposed “CPI” index for the U.S. going back to the early 19th century, compared to a raw commodity index for the same time period. They are basically identical before 1880 or so, and don’t differ by all that much before 1940. The CPI since 1970 or so has not had much direct connection with raw commodities at all.

March 3, 2016: the Myth of “Price Instability” During the Gold Standard Era

In the last fifteen years or so, the CPI has, at times, approached something like complete fictionalization. So, the correct answer is somewhere between “it is constantly changing” to “whatever the government wants it to be.”

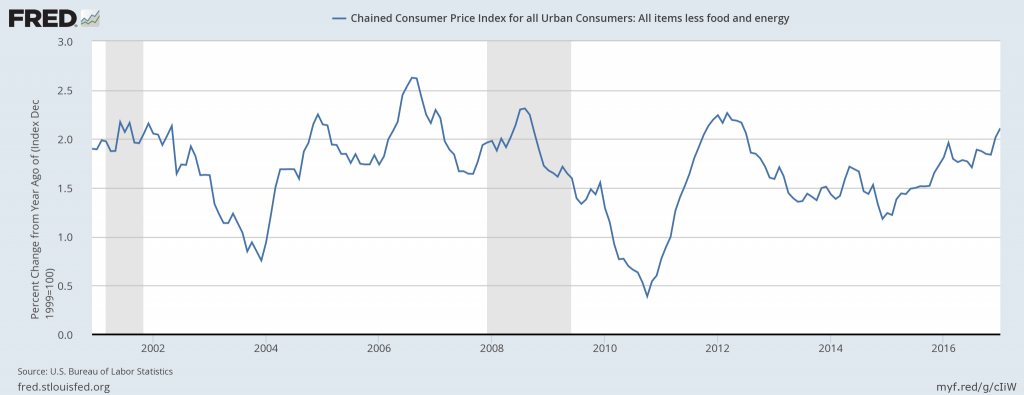

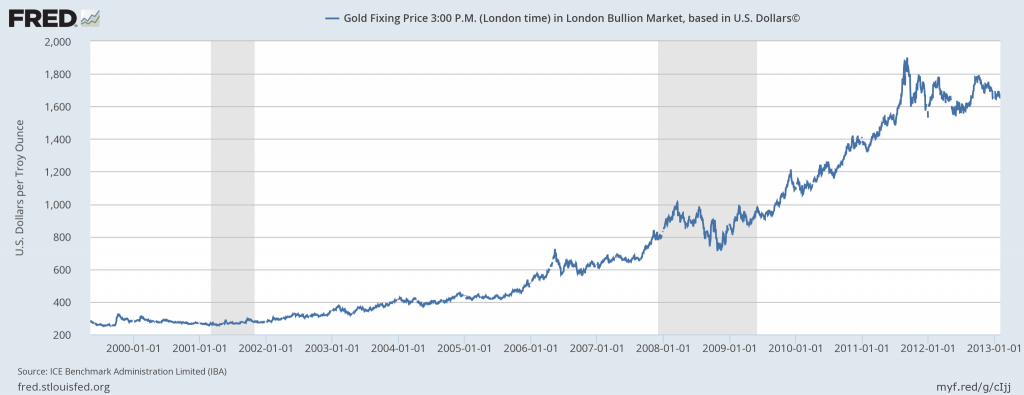

For example, the notion that the CPI (in the popular less-food-and-energy configuration) was rising at a sub-2.5% rate in 2002-2008, a time when the dollar price of gold rose from $250 to $1000, with confirmation from all commodities including a rise in crude oil from $20 to $140, is basically a sort of intelligence test. This is fiction.

I’m not sure that the CPI is much more than a sort of propaganda these days.

Nevertheless, there are a few principles that apply. As I see it, there are two basic sorts of influences upon the CPI, or some other similar sort of price index. The first group is monetary; the second is non-monetary.

The idea that changes in currency value (such as the Mexican peso devaluation in 1995) lead to changes in the CPI (“inflation”) is not terribly surprising, although it is always a marvel at how many “economic experts” have difficulty with even this idea.

But, I would like to talk about the non-monetary effects. Unfortunately, many people who have a good grasp of the monetary influences sometimes neglect the non-monetary ones.

The “non-monetary effects” tend to be summed up as: growth makes the CPI go up; contraction makes it go down.

This is one reason for the “2% per year” mantra that central bankers talk about. In a healthy growing economy, you would tend to see CPI increases of about 2% per year, I would say, from growth effects. So, you wouldn’t want to have a CPI target of 0%, which would create problems.

In a healthy growing economy, and assuming a currency of perfectly stable value, some prices would go up, and some prices would go down. Wages, in general, would go up, as the result of increasing productivity. This is the “growth” beyond the factor of population alone. As wages go up, prices for services tend to rise, and also rents and real estate. This is obvious today, when you compare any two places with different average incomes. Let’s take, for example, Albany and Manhattan. Everything that is service/real estate related, such as a restaurant or doctor or school, is much more expensive in Manhattan; and this has something to do with the higher incomes of Manhattan, compared to Albany. However, manufactured goods or commodities are the same price in either location. For an even bigger difference, you could compare Manhattan and El Salvador, which have wildly different price structures although El Salvador has been dollarized for a long time, and the two locations thus share the same currency.

It is conceivable that something terrible could afflict Manhattan, making it as poor as El Salvador today. Nearly this has happened in Argentina. Something wonderful could happen in El Salvador, making it as wealthy as Manhattan. Nearly this has happened in Hong Kong. Then, prices in Manhattan would be much lower than El Salvador, just as prices in Hong Kong are much higher than prices in Myanmar.

While service/real estate-related things tend to rise in price, as incomes increase, most manufactured goods decline in price. This has been true for a long time for all kinds of electronic goods, but it was also true in the late 19th century for things like iron and steel (and things made from them), and in the early 19th century for things like cotton cloth.

On balance, however, in a healthy economy the things rising in price tend to outweigh the things falling, and the CPI typically rises.

Economic contraction is associated with falling prices, with the Great Depression an example of the concept.

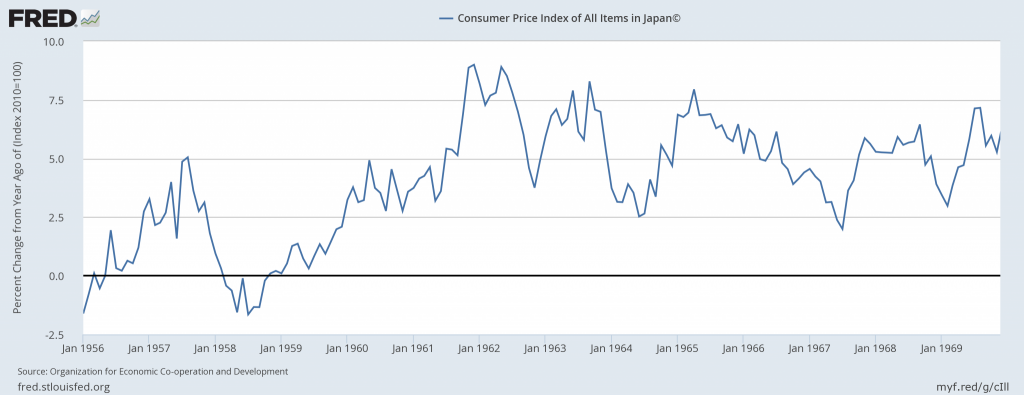

In a high-growth economy, it is possible to have rather extraordinary CPI rises on the order of 6% or so, from growth alone, even with a currency of stable value such as the Bretton Woods gold standard of the 1950s and 1960s.

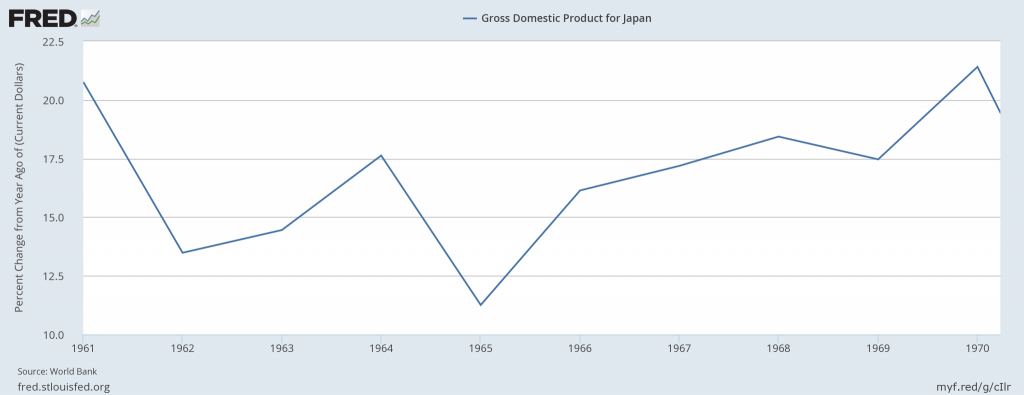

The raging 15%-per-year nominal GDP growth of Japan in the 1960s corresponded to measured CPI increases on the order of 5%.

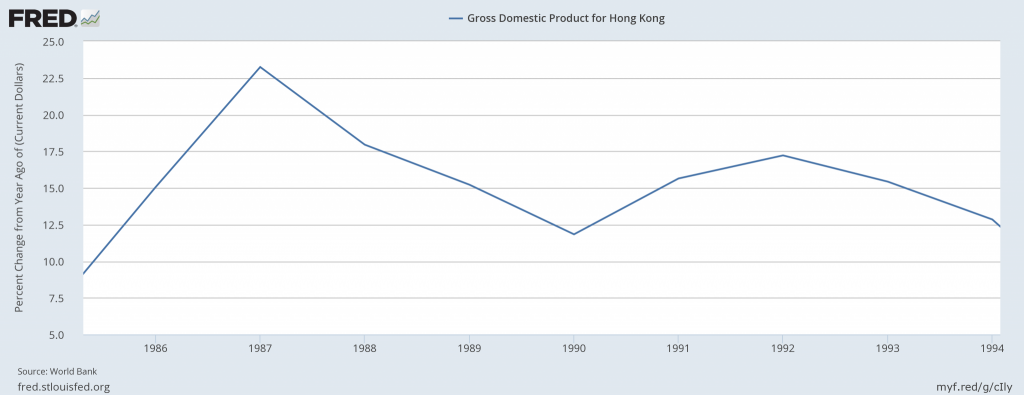

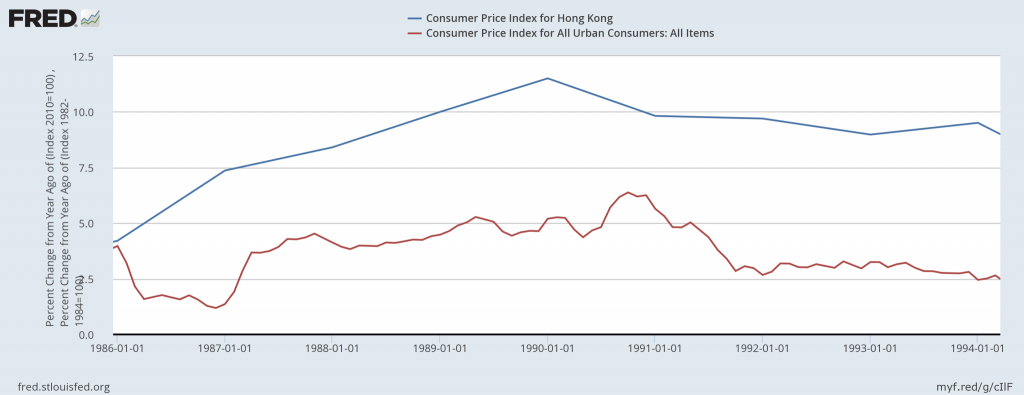

Hong Kong in the early-1990s is a little harder to figure, because I think there was still some leftover inflation from the 1970s around that time. But, it showed a similar pattern, despite having been on a dollar currency board for some time by that point.

Again, we have 15%-per-year nominal GDP growth.

The Hong Kong CPI was showing increases of about 9% per year, even while the U.S., with effectively the same currency, was around 5% — falling to 2.5% after 1992.

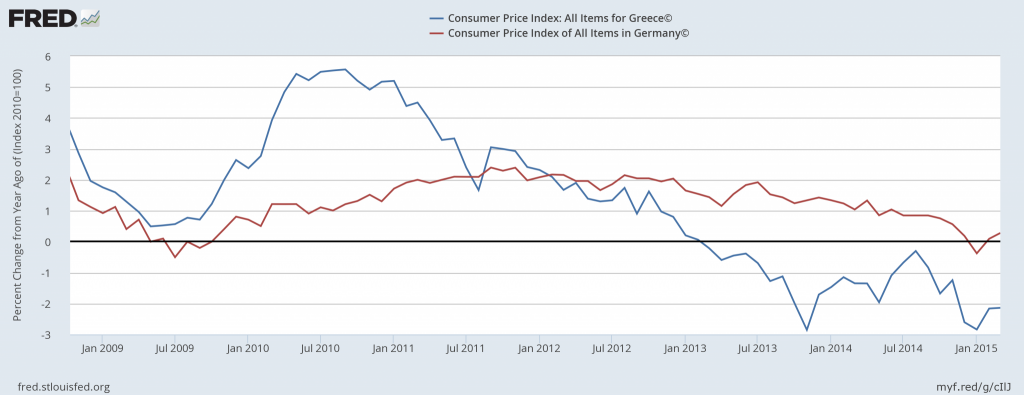

With all this in mind, it will surprise nobody that the CPI in Greece has gone negative for some time, along with Greece’s nominal GDP, while the CPI in Germany has remained positive. Even Germany’s economy is not all that healthy right now, much like that of the U.S.

Now, I should mention that, although the Japanese CPI was rising at a fast clip in the 1960s, commodity prices (in terms of dollars or yen) were about as dead flat, during the 1950s and 1960s, as any economic statistic can be. A lot of the idea that “a gold standard leads to unchanging price levels” is related to commodity prices, and price indices closely related to commodity prices, which is just about everything before 1940.

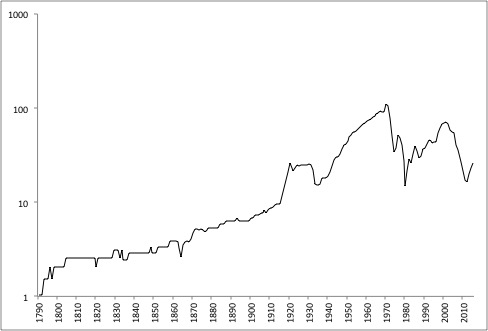

This is a chart of the value of 1000 hours of work (wages) in terms of gold oz., 1790-2016. It is from measuringworth.com. As we can see, it has been rising for a long time — so long, that I had to use a logarithmic scale. I would guess that prices for services/rents & etc. rose alongside wages then, just as they do today.

Since we might like to have growth like Japan of the 1960s — 15% per year nominal, with a gold standard currency of stable value — we should also be prepared to have perhaps 5%-7% annual CPI increases along with that. This is not “price stability.” We don’t want “price stability,” we want stability of currency value, as Japan had (more or less) within the Bretton Woods system. Similarly, a negative CPI of -2%, or even more negative, can certainly come about with a currency of stable value, when non-monetary factors are causing economic contraction.

None of these conclusions are particularly surprising. I hope most people find them rather commonsensical. And, they have been around a long time, at least since the days of Ricardo. But, only a small portion — I would guess under 10%, maybe way under — of today’s “economic experts” comprehend these concepts. You will notice this, going forward, as you read some of what they write and say.