Question About Japan

September 26, 2010

Some friends asked me about some recent developments, and here’s what I had to say about it:

Q (paraphrased): It looks like the BOJ didn’t sterilize the recent forex intervention. What does this mean going forward?

Since you mentioned it, I started looking a little bit at the BOJ’s actions recently. I haven’t done much BOJ-peeping in about eight years I think. It appears that the most recent intervention was “unsterilized” for now.

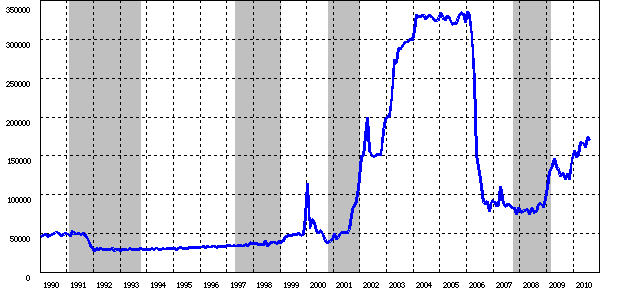

Anyway, the most interesting thing thus far is this:

This is a graph of the BOJ’s bank reserve accounts (aka “current accounts”). You can see the “QE” period 2001-2006 clearly. However, the interesting thing is that this has been creeping up again beginning in late 2008, in line with similar expansions at the Fed and ECB. The graph is in “100 million yen” increments (this is a round “oku” or 10,000×10,000 in Japanese). Since 100 yen is about the same as a dollar, you could think of it in $1 million increments. So, 150,000 X $1m is about $150 billion. The most recent intervention was for about $20 billion I think, so that would result in an expansion of bank reserve accounts by about $20 billion (20,000 X 100m yen), and indeed that is what appears to have happened at least for the last couple days.

Also, this is in line with a trend toward a “new QE” in Japan that began in late August:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/7972098/Japan-renews-QE-as-recovery-falters.html

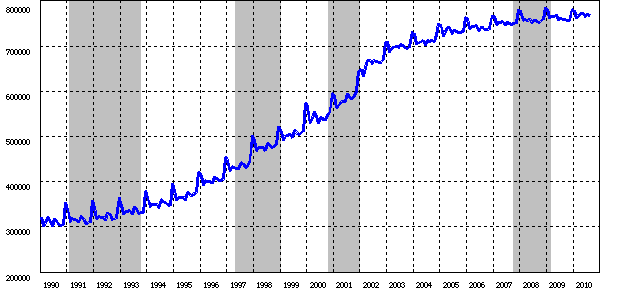

These are banknotes in circulation. Note the rather abrupt slowing of the growth rate at the beginning of 2002. This corresponds exactly with the QE and also the beginning of the decline of the yen vs. gold. In other words, as the real value of the yen rose (falling yen gold price), demand for banknotes grew, and as the real value of the yen began to decline, banknotes became less popular.

Not too much you can say about it at this time, but it does appear to me that since late 2008 we have had a newer sort of BOJ regime in which bank reserves are allowed to grow slowly. This is much like the Fed, which just goes to show what I mean about central bank policy being a “monkey see monkey do” affair.

You can see why BOJ and MOF don’t get along that well. MOF is generally responsible for forex intervention. However, the results of yen-selling intervention end up on the BOJ’s balance sheet, immediately as an expansion of bank reserves and long-term as an expansion of base money generally. This would cause a probable deviation of the overnight bank rate from the BOJ’s target rate, at least it would back when there was a target rate above 0.50% or so. Thus, if MOF’s interventions were “unsterilized,” the result would be in effect a “change in interest rates,” and the BOJ considers that its turf.

Today of course, with ZIRP the effect instead is a change in bank reserves. Thus, more MOF interventions would have the effect (if unsterilized) of expanding bank reserves, which the BOJ considers its turf as part of the “QE” format that it has adopted now that it can’t fiddle with interest rates here. Thus, MOF’s interventions would be sterilized on the basis that it would cause bank reserves to vary from the BOJ’s target. And that’s pretty much the way it has been for at least twenty years.

However, today it appears we have a more flexible sort of arrangement, whereby bank reserves are at least allowed to vary somewhat and are not pegged at some flat-line level as part of a “QE” target. This is “good” in the sense that we don’t have a policy framework that effectively mandates sterilization. The ultimate measure of whether forex intervention is “sterilized” or not is whether the monetary base permanently grows in 1:1 proportion to the yen-selling intervention, compared to what it would have been without the intervention. Bu “permanently” I mean that the BOJ doesn’t remove the funds a week or a month or three months later, simply postponing its sterilization for a little while for political reasons. Thus, if we have a series of Y2 trillion interventions, let’s say five of them, then the monetary base should grow by roughly Y10 trillion. In the first instance, this would likely be concentrated in bank reserves, so bank reserves would grow from Y17.5 trillion-ish today to Y27.5 trillion. More or less.

You can see that the last round of intervention, around March 2004, was completely sterilized.

Q: Why is the yen so strong? You’d figure it would be weak considering the easy money policy and the government’s poor finances.

The persistent strength of the yen is a bit of a bizarrity to me. I can really only make up hypotheses, which may or may not be accurate.

Technically, the BOJ can certainly lower the value of the yen. The easiest way would be to simply sell “freshly-printed” yen in unsterilized forex “intervention”, in other words buying dollars or euros or what have you. Since CB’s don’t actually hold paper banknotes, what this really means in practice is buying foreign government bonds. (They buy the currency, then trade the currency for bonds almost immediately.) This is not really all that much different than buying domestic government bonds with the “printing press.” The fact that a forex transaction is involved, however, would make the process a little more direct if your goal is to lower the forex value of a currency.

In the past, the BOJ sold yen and bought forex in “sterilized” intervention, which was rather ineffective. If you pursue this “unsterilized forex intervention” systematically and continuously, with the goal of maintaining a stable exchange rate, you end up with a currency board.

This leaves the question of why the BOJ’s past QE (mostly unwound now) and present ZIRP hasn’t resulted in a lower currency value.

Actually, it has resulted in a lower currency value. The yen/gold ratio has been steadily rising, showing a falling yen value along with all other major currencies. The yen just hasn’t fallen as much as the euro or the dollar. So, it’s strength has been “relative” rather than “absolute.”

I suspect that what has happened is that Japanese banks actually want to keep large bank reserve accounts at the BOJ. In other words, the demand for “riskless” money or “cash” is high. This is common when banking systems are under stress. It was true of U.S. banks in the 1930s, and it is true of U.S. banks today. When banks are worried about short-term funding risk, and they aren’t getting paid to take counterparty risk with other banks in the interbank lending market (low rates), then you might as well sit on a mattress of cash at the BOJ. In other words, low overnight rates reduce the opportunity cost of holding no-yield cash.

However, the BOJ began to withdraw this “excess” bank reserves in mid-2006, which coincides nicely with a new rising trend for the yen/dollar from the 120/dollar range that it had stabilized around previously. I mentioned this at the time:

http://www.newworldeconomics.com/archives/2006/061106.htm

In other words, the BOJ’s “supply” of base money (including bank reserves) is in relative shortage compared to the “demand” (from banks to have “mattress money”), so there is a strong-yen tendency although in absolute terms (vs. gold), the yen has been sliding like every other major currency.

But, as I said, I am guessing here. That’s my best guess. These things are never very clear.

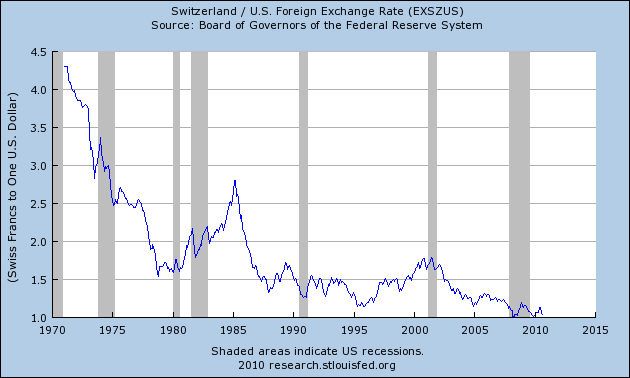

The yen does illustrate a factor which will be important going forward: major currencies just can’t serve as a viable alternative when the leading international currency is devalued. The trade effects simply become too strong. In the 1970s, Switzerland tried to stick with the gold standard, or at least pursue a less-inflationary policy, but the forex rates got so out of whack that they simply couldn’t stick with it. This is why an inflationary policy for the leading international currency (especially when mirrored by a few other major currencies) soon becomes a worldwide policy.

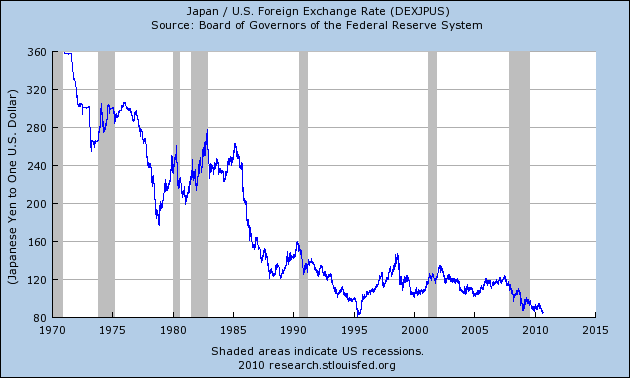

This was also true of Japan in the late 1970s. The surge from about 300 yen/dollar to 175 yen/dollar — this while the dollar was tanking vs. gold in the late 1970s — was just too much for Japan, which then switched to what amounted to a policy of stabilizing the yen around 240/dollar.

People say the original QE in Japan beginning late 2001 wasn’t effective. Actually, it was effective. The yen’s rise vs. gold (“falling yen/gold price”) ended right around 2001, when QE began. This rising yen vs. gold was the reason for “deflation” (monetary distortion) in Japan during the 1990s.

When QE ended in mid-2006, the yen had fallen to around 70,000 yen/oz. which is really quite a large move and returned the yen to about its 1985 level. QE was ended in 2006 because increasing “inflationary” pressures were becoming apparent. Today, the yen is around 100,000/oz. so “deflation” in the monetary sense is really over in Japan. As is the case in the United States, currencies have been losing value, which has “inflationary” consequences although this has been masked by the general economic downturn.

However, Japan’s economy is today suffering from a number of factors. One of course is the general worldwide economic slump. Second is the trade consequences of the high yen vs. other currencies. Third is the rather strong trend toward higher taxes in Japan, which I’ve covered a bit in the past.

November 1, 2009: Japan’s New Government

May 24, 2008: Japan: Silly Self-Destructive Behavior

May 18, 2008: Japan: Tax Hikes are No Fun

April 21, 2008: Japan — WTF is Going On Here?!?

April 13, 2008: This Is So Not Like Japan