Some Gold Standard Technical Operating Discussions

January 8, 2012

I’ve been having some discussions with a friend about technical operating mechanisms for a gold standard system. What would be best?

In some of my recent writing for Forbes.com, I’ve made the point that a “gold standard system” is actually a rather broad and vague term. It means a policy of maintaining a currency’s value equivalent to gold, at some parity ratio. However, within that context can be a great many variations on exactly how it gets done.

November 17, 2011: My Thoughts on Lewis Lehrman’s Gold Standard

Our discussions are regarding redeemability of gold bullion, and the use of open market operations using bonds. These are both ways to manage the base money supply, by buying and selling assets. When you buy an asset, the asset (gold bullion, bonds, or perhaps something else) is paid for by creating money “out of thin air.” This money appears in the seller’s bank account, but it is not debited from an existing account. When you sell an asset, the money received in payment disappears, thus shrinking the monetary base.

December 1, 2011: What is Money?

Let’s assume that you have a policy of gold redeemability. In other words, the monetary authority is willing to sell gold, and take base money in return, at a certain price. This might be the parity price, or it might be a percent or two away, creating a “trading band” around the parity price. When the monetary authority sells gold in this fashion, the money received disappears, and thus the base money supply shrinks. You can also have a gold standard system without gold redeemability — one that uses non-gold assets such as bonds exclusively — but this has been rare historically.

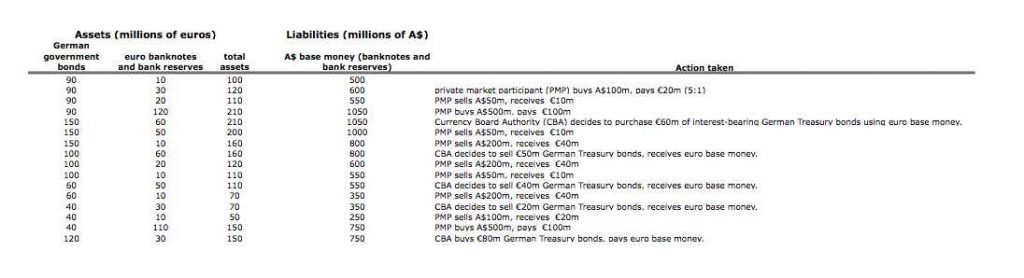

Let’s say you have a conventional currency board, that links one currency with another. Country A has a currency board that links its currency to the euro at a rate of 5:1. Thus, A$5 per €1. There is base money of A$500 million, and the currency board authority holds €100 million. The currency board authority is willing to either buy or sell A$ in any quantity, in trade for euros, at A$5 per euro. Or, maybe there is a little trading band or bid/asked spread, so the currency board authority will buy A$5 at €0.98 and sell A$5 at €1.02. When the currency board authority sells A$, it does this by creating new A$ “out of thin air,” and taking euros in return. Thus, the amount of A$ in existence (A$ base money) increases, and the reserve holdings of euros increase. When the currency board authority buys A$, and gives euros in return, these A$ disappear from existence, and the reserve holdings of euros decrease.

The currency board authority rarely holds an actual €100 million of euro base money — literal bundles of banknotes, or a reserve deposit at the ECB. Typically, the currency board authority might hold a little euro base money, perhaps €10 million (10% of reserve assets), and the rest of the reserve asset holdings will be in the form of euro-denominated German government bonds.

The currency board authority can also adjust its reserve holdings. For example, if it feels that it has too much non-interest-bearing euro base money, it can use the euros to purchase a bond asset, such as euro-denominated German Treasury bonds. If it feels that it doesn’t have enough euro base money, it can sell some German Treasury bonds and receive euro base money in payment. These actions don’t change the monetary base.

It looks something like this:

Note that both buys and sells in this system, which create changes in A$ base money, arise wholly from someone approaching the currency board authority (the “private market participant”), to buy or sell A$ at the prices indicated. The currency board authority does not instigate any buys or sells on its own. Thus, the currency board system is wholly automatic, with no discretionary element, even on a day-to-day basis.

The quantities in this example are rather large. Normally, the changes as a percentage of assets would be quite modest. Also, most foreign exchange transactions (buying/selling A$ and euros) would be between two private market participants. The CBA’s contribution would be if there were more buyers than sellers, or more sellers than buyers, at the indicated parity price.

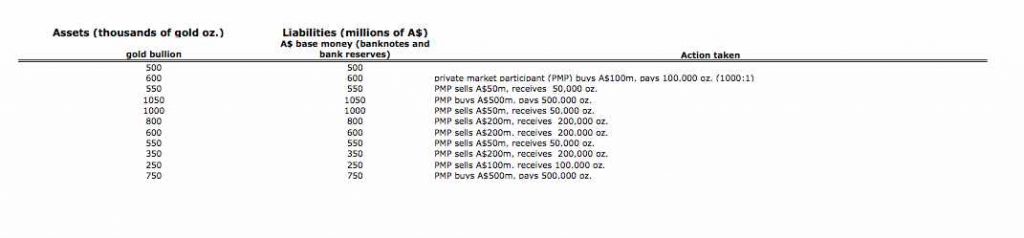

This system, a “currency board” system, links one currency with another currency. We can use the same mechanisms to link a currency to gold. In this case, the gold standard authority (GSA) is willing to buy or sell gold at, let’s say, A$1000. Of course there could be a little buy/sell spread of a couple percent as described earlier. For now, let’s assume that the GSA’s reserve asset is gold bullion exclusively, or a “100% bullion reserve” system. Note below that I’m using “thousands of gold oz.” and “millions of A$”, so there’s the 1000:1 ratio right there. It looks like this:

The terminology “buys A$100m, pays 100,000 oz.” is a little odd, but the transaction is exactly the same as our euro currency board example. When I say that they “pay 100,000 oz.,” I mean that they actually deliver 100,000 of physical gold bullion to the GSA, and receive A$100m in return.

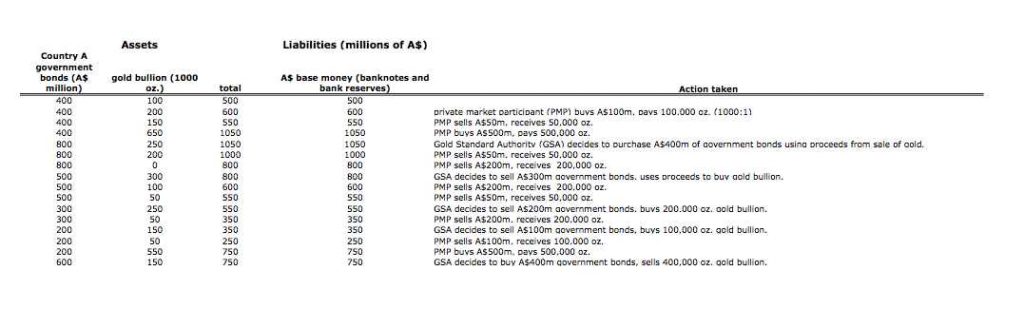

This kind of “100% reserve” system basically did not exist in the last three hundred years. The Gold Standard Authority (in practice commercial banks, and later central banks) typically held most of their reserve in the form of government bonds, or perhaps high-quality corporate bonds. However, unlike our euro currency board example, where we use foreign government bonds (German Treasury bonds), they could use domestic government or high-quality corporate bonds. (In practice, many used foreign government bonds in a gold-linked currency, such as British Consol bonds. This works fine too.)

The domestic government bonds are denominated in A$, and since the A$ is linked to gold, the domestic government bonds are linked to gold too. Thus, if the central bank wants to reduce its bullion holdings and increase its interest-bearing bond holdings, it would sell the bullion on the open market for A$, and then use the proceeds of the sale to purchase domestic government bonds (or foreign government bonds, same thing). It would look something like this:

In fact, gold standard systems such as those of the Bank of England, or those operated by hundreds of private commercial banks in the U.S., worked along these lines. Do you see why I say that a gold standard system is like a “currency board linked to gold”? Pretty obvious, don’t you think.

We didn’t even get to the topic at hand today. Maybe next time.