The Composition of U.S. Currency

January 16, 2010

“Money” is really what is technically known as “base money.” “Base money,” in turn, is mostly — typically about 90% — banknotes and coins. So let’s take a look.

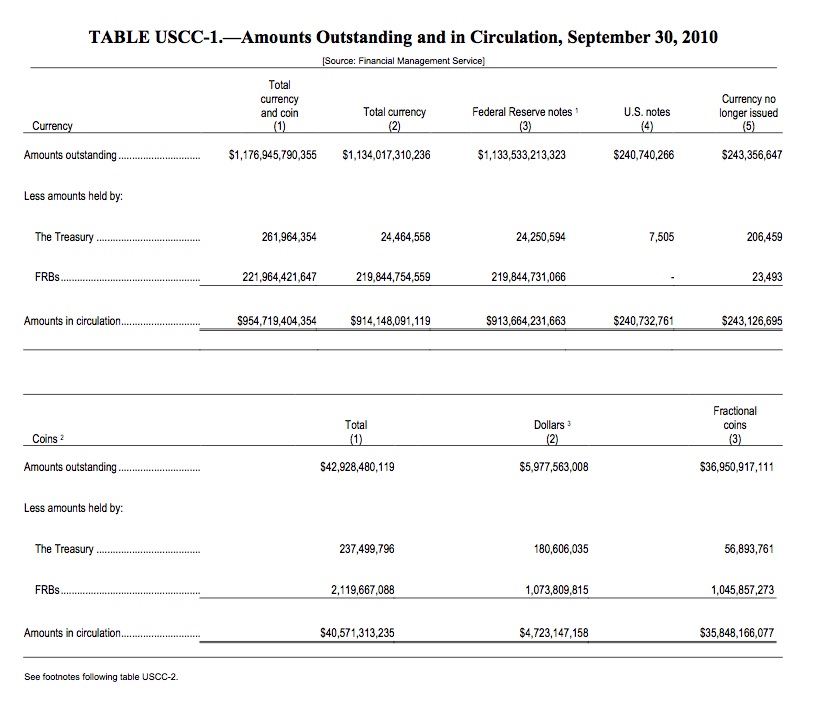

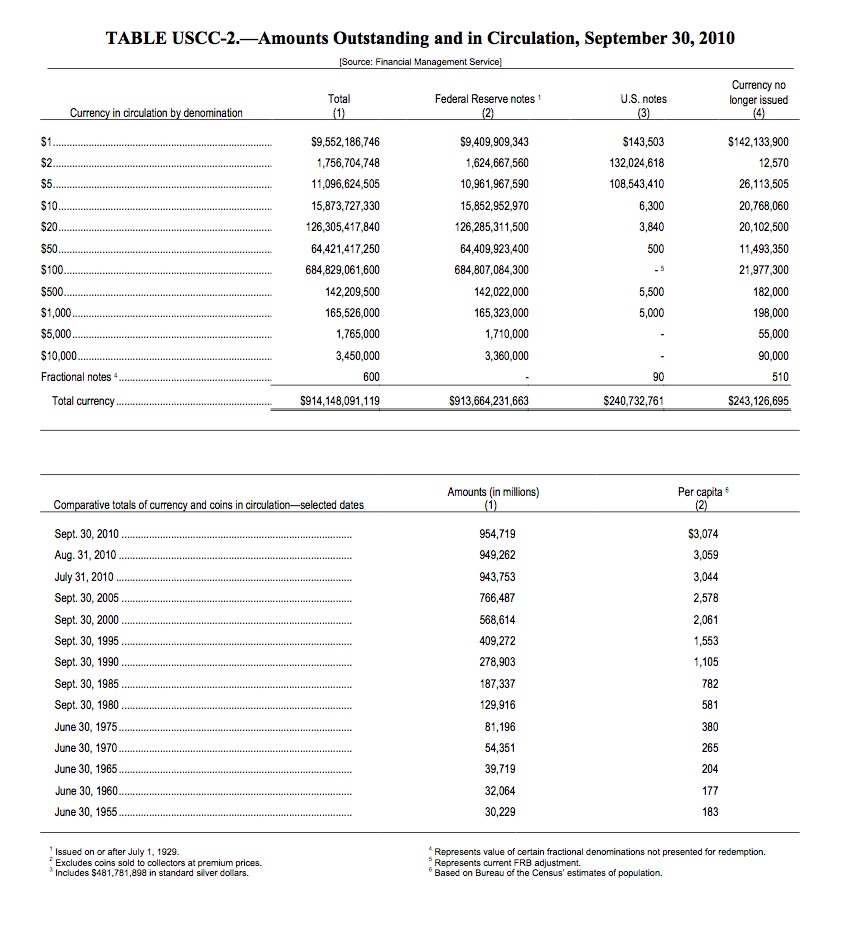

Here we see that there were $9.4 billion of $1 bills, $16 billion of $10 bills, $126 billion of $20 bills, and $685 billion of $100 bills. Indeed, of the $914 billion of Federal Reserve Notes in circulation, 75% is in the form of $100 bills. The total circulation of all of the banknotes of $10 and less amounts to $37.8 billion, or only 4.1% of the total.

This should make you think a bit. When was the last time you even saw a $100 bill? I don’t think I saw one last year. Most people use $20s, and a credit card or check for larger amounts. Where are all these $100 bills? What are they used for? They must be useful for something, or all the people who have those $100 bills would trade them in for some sort of interest-bearing note (maybe not so much today since interest rates are low). For example, they could deposit them at a bank. The bank, if they had more $100 notes than they needed, would then give them to the Fed in exchange for electronic bank reserves (in effect a deposit at the Fed).

Next, we see that there are $3,074 of notes and coins in circulation for each person in the United States. Look in your wallet. Do you see $3,074 there? If you have a family, multiply each person by $3,074. Does your family of four have $12,296 of banknotes in their wallet, sock drawer, safety deposit box etc.? Probably not, I’d say. This also includes banknotes held by businesses, in the cash register and so forth. But, that is not really all that much either. Businesses don’t like to hold a lot of cash, because it can be stolen. I remember not too long ago that I couldn’t get change for a $20 bill at an Au Bon Pain in Boston.

One thing to ask here is: how were these proportions determined? I talked about this extensively in my book, and I don’t think I will review that here. Go buy and read the book. I can tell you what didn’t happen: there wasn’t some sort of committee meeting in which they said “well, I think we should have banknotes in circulation of $914 billion this year, of which $684,807,084,300 consists of $100 notes. Shall we vote on it?” These proportions arise due to the automatic performance of the banknote convertibility system. If people want to hold more $20 bills and fewer $50 bills, then they take their $50 bills to the bank, and ask for $20 bills. On the aggregate basis, banks end up with lots and lots of $50 bills and they have a shortage of $20 bills. So the banks go to the Fed and say “here, take these $50 bills and give us some $20 bills.” The Fed does so. In this way, the amount of $20 bills in circulation increases and the amount of $50 bills declines. A currency board works almost the same way, but instead of $50 bills and $20 bills, banks will exchange Hong Kong dollars and U.S. dollars. A gold standard also works in a similar way, as it amounts to a “currency board linked with gold” instead of a currency board linked with some foreign currency.

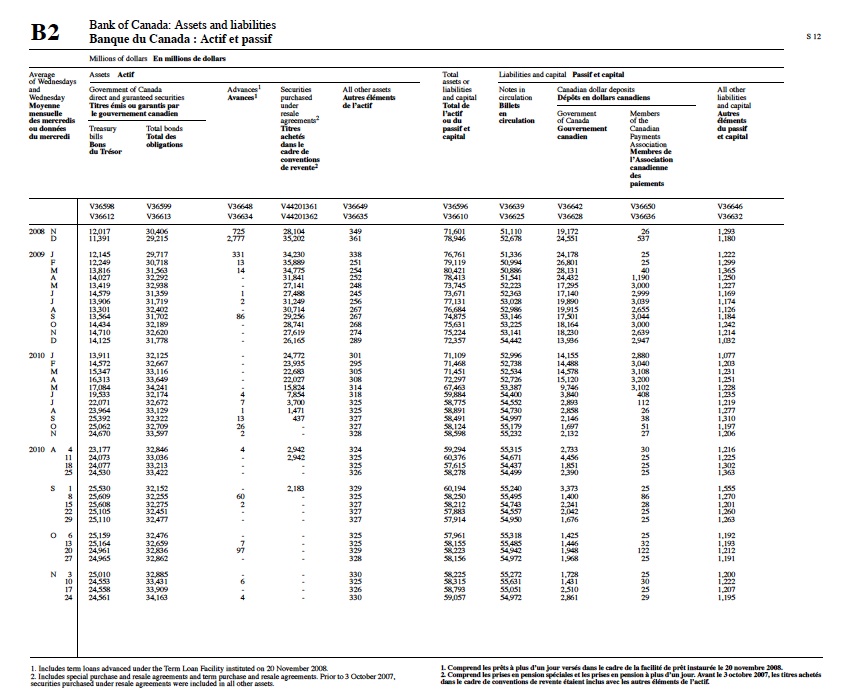

Here we see that at the end of November 2010, the Bank of Canada had banknotes in circulation of $54.972 billion. It works out to $1,617 per person. About half that of the U.S. Still a pretty big number, though.

Nobody really knows where all this money is. But we can guess. Most of those $685 billion of $100 bills are probably used either in illegal/under the table transactions in the U.S. (notably in the drug trade), or outside the country. I would guess that only about $100 billion of U.S. banknotes is actually used by normal law-abiding people. This works out to about $320 per person, and would include perhaps $25 billion of banknotes of $10 and under, plus another $75 billion of $20 bills. Judging by the statistics from Canada, I would say that at least half (could be higher) of all U.S. currency is circulating outside the U.S. Although we hardly ever see transactions today in the form of bundles of $100 bills, it is not too uncommon elsewhere in the world. Every large business in Argentina, for example, had a safe with bundles of U.S. dollar banknotes to engage in large transactions, particularly during the hyperinflationary 1980s. Even later, it was common to engage in large transactions, such as buying a house, with a briefcase of U.S. dollar banknotes.

From this, you can see how inane it is to make economic assumptions based on U.S. statistics alone. Most of the people using the U.S. dollar are not even in the U.S.! We can also see how the demand for dollars can change for all number of reasons. Mabye Argentines stop buying houses with cardboard boxes of dollar bills, and start using euros or Swiss francs (or internal bank transfers) instead. This would lead to a decline in the demand for U.S. banknotes (“dollar base money”). This would then have to be met with a decline in the supply of base money (banknotes taken out of circulation), or the value of the dollar would fall. The Keynesian economists would panic at the drop in the “money supply,” ascribing all sorts of consequences to it, when it was just the normal adjustment of supply to a decline in demand. Likewise, maybe currency collapse in India leads people to do all their business with wads of U.S. dollars, like Argentines did. To accomodate this new demand for banknotes, the Fed and Treasury would have to print some up. The Austrians would then be in a tizzy over the “expansion in the money supply.” Go complain to the Indians. Of course the Monetarists and their “velocity of money” indicators would be all over the map, which would make the Monetarists start to spout all sorts of idiocy as well. And you wonder why today’s economists always get it wrong, and blow things up whenever they are allowed to actually participate in policy decisions.