The Federal Reserve in the 1920s

November 18, 2012

A friend asked me some questions about the Federal Reserve in the 1920s. For the most part, the Fed was adhering to the principles of a gold standard system, after a rather wrenching postwar adjustment in 1920-1921 that we looked at earlier:

March 25, 2012: The U.S. Dollar During WWI and the Recession of 1920

However, as I wrote about in my book Gold: the Once and Future Money, the Fed was, already by the 1920s, not really acting as was intended in the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. The Fed was intended to be dormant most of the time, springing into action only during the occasional 1907-style liquidity shortage crisis, when the rate on overnight loans rose to unusually high levels typically above 10%. However, during WWI, the Fed had already been pressured into acting on a daily basis by the Treasury, to cap interest rates and thus allow the Federal government to issue debt to fund the war at attractive levels. This resulted in excessive Fed money creation and a deviation of the dollar’s value from its gold parity, as documented earlier.

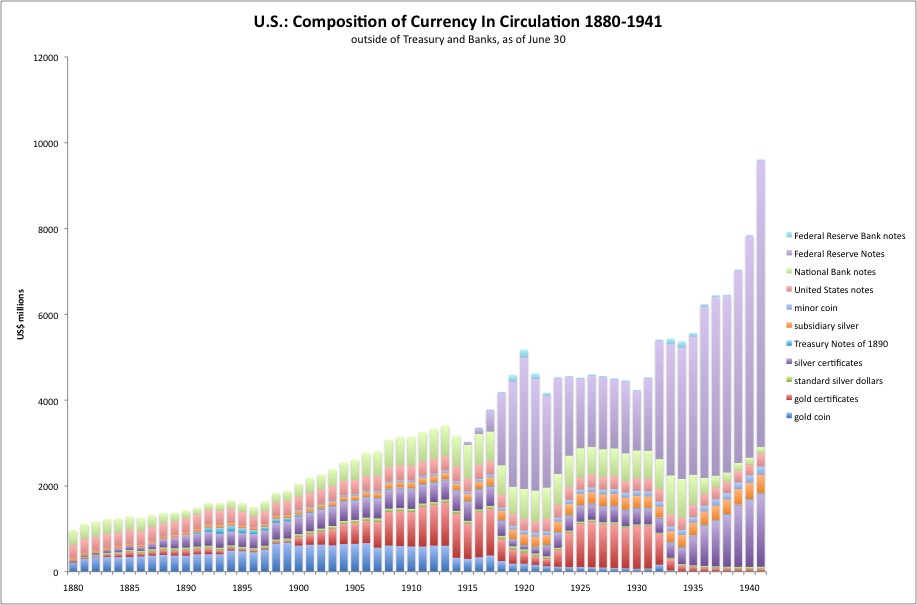

Thus, by 1922 or so when our story begins here, the Fed was already accustomed to acting on a daily basis in markets. Also, the Federal Reserve Note had, as a result of the money-printing of WWI, become the dominant banknote in circulation, accounting for roughly half of the U.S. currency in circulation during the 1920s. The rest of the currency consisted of National Bank Notes, issued by hundreds of smaller commercial banks, and also U.S. Treasury-issued currency including gold certificates, silver certificates, and silver coins. In those days, a silver coin did not trade at the market value of its contained metal. The contained silver of a silver dollar was worth less than a dollar. Thus, silver coins were also somewhat like paper money in those days. They were token coins, managed by the Treasury. By that time, the U.S. was officially on a monometallic gold standard, following the Gold Standard Act of 1900.

July 15, 2012: The Composition of U.S. Currency 1880-1941

Gold coins circulated as well, notably the beautiful Saint Gaudens $20 Double Eagle, which contained just less than an ounce of gold.

1922 Saint Gaudens $20 gold coin.

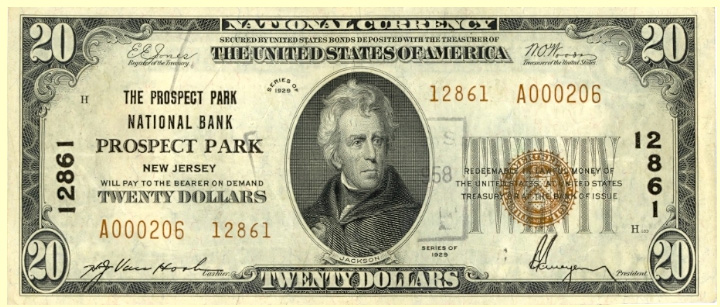

Here’s a National Bank Note from 1929, issued by the Prospect Park National Bank, in Prospect Park, New Jersey:

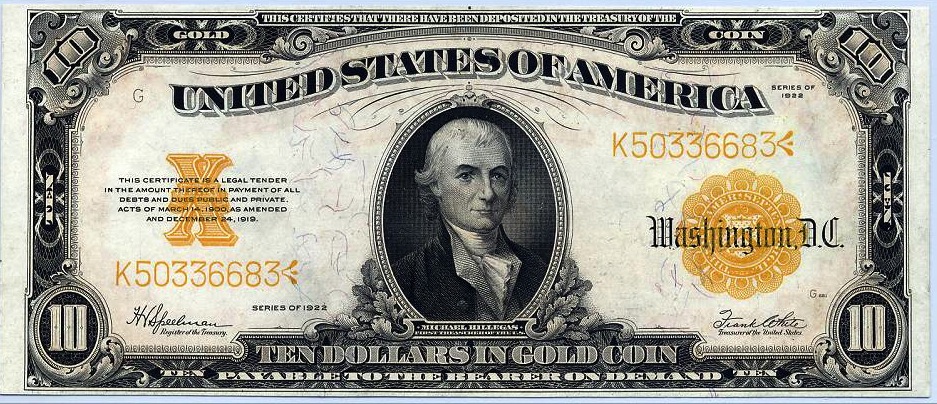

As part of the National Bank System that began in 1863, my understanding is that individual banks did not hold gold bullion as they did prior to 1863. Instead, it was centralized at the U.S. Treasury. The National Banks held U.S. Treasury bonds instead, which is why the note says “secured by United States Bonds Deposited With the Treasurer of the United States of America.” The banknote also does not have the world “gold” on it, as prior banknotes did, but rather that the bank would pay “twenty dollars.” I believe this “twenty dollars” would normally take the form of a Treasury gold certificate, like this 1922 $10 gold certificate:

Now, this note is very explicit: “This certifies that there have been deposited in the Treasury of the United States of America Ten Dollars in Gold Coin Payable to the Bearer on Demand.”

Here’s a Federal Reserve Note from 1928:

It says: “Redeemable in Gold on Demand at the United States Treasury, or in Gold or Lawful Money at Any Federal Reserve Bank.”

The point here is: after the World War I gold embargo was lifted in 1919, the paper currency of the U.S. was redeemable in gold. Indeed, it was the wave of redemption beginning in 1919 that pushed the Fed to remedy the wartime excess base money creation, which we documented earlier. So, we know it worked. This was the case up until 1933, when redemption was suspended.

The 1920s were a time when there were still multiple issuers of currency, the “parallel currency environment” that some people would like to return to today. If the Fed was chronically mismanaging the Federal Reserve Note, the part of the currency system it was responsible for, people would naturally migrate to alternatives, probably either the Treasury gold certificates, the National Bank Notes, or even gold coin itself. This did not happen; instead, the Federal Reserve Note became more dominant during the decade, while gold coins slowly fell out of favor.

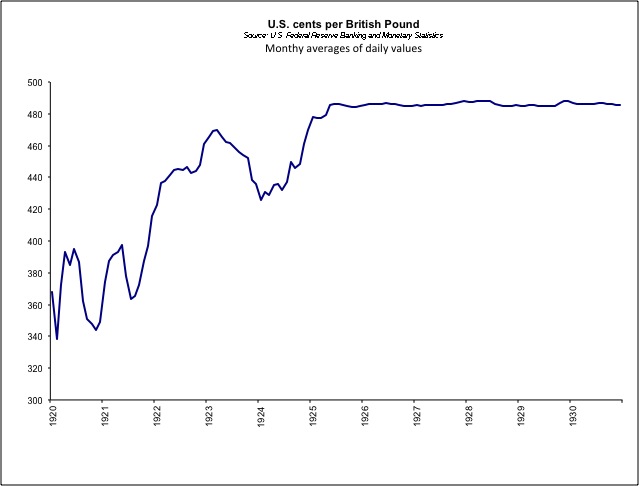

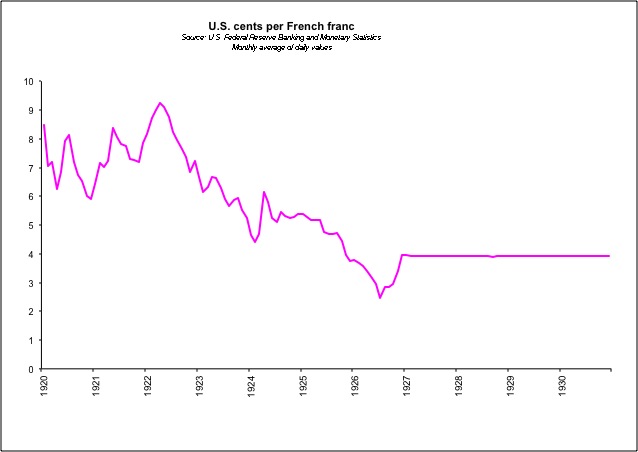

Most European currencies were not relinked to gold until around 1924-26. However, after 1925, we can also compare the value of the dollar to other, independently gold-linked currencies like the British pound, French franc or Swiss franc. During the Bretton Woods system 1944-1971, this is not so useful because European currencies were overtly linked to the dollar directly. So, you can’t get an idea of variation in the dollar’s value from looking at forex rates. However, during the 1920s, countries maintained independent links to gold directly. So, if the dollar’s value was varying from its gold parity at $20.67/oz. by some meaningful measure, it should show up in changes in forex rates compared to other gold-linked European currencies. Let’s look at a few.

April 15, 2012: Foreign Exchange Rates 1914-1941

We can see here Britain’s process of returning to a gold standard in 1925. Afterwards, there is a straight line, indicating that the dollar’s value did not vary by much at all from the independently gold-linked pound.

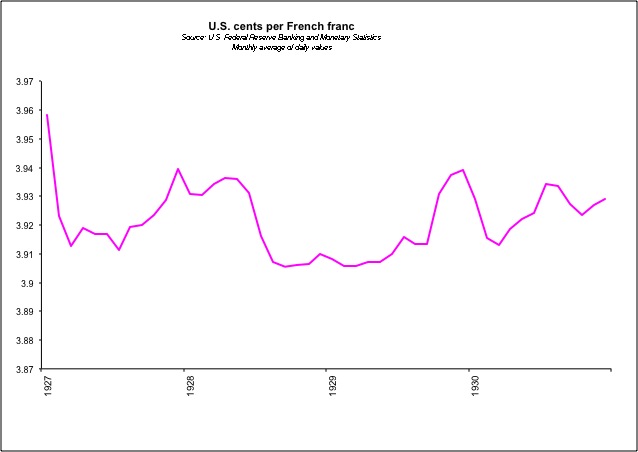

However, it did vary a little bit. This is a closeup of the pound/dollar exchange rate from 1925-1930. Remember that a 1% move here is about 4.8 U.S. cents. We see that there was a little variation in exchange rates, but less than 1%. These variations are somewhat significant from the standpoint of a gold standard stable value policy. Stable value means stable value, with no variation at all. So, a 1% deviation from the ideal might be significant, compared to the expectation of perfect stability. Central bankers might have a phone call and say: “you guys in London should maybe sell a few gilts, reduce the monetary base, and bring the value of the pound back to where it is supposed to be, don’t you think?” However, in terms of the economy as a whole, these sub-1% wiggles are totally irrelevant.

From all of this, it is fairly easy to conclude that the dollar was indeed worth 1/20.67th of an ounce of gold during the 1920s, the promised gold parity — or, at least, within a quite small range of that ideal target, deviating by apparently less than 1%. The only way to accomplish this, especially in this time when capital flowed freely, before the Bretton Woods-era capital controls, is to manage the gold standard system properly, or at least acceptably close to properly. For some reason, people have a hard time with this. They want to believe that the Federal Reserve was up to some kind of disastrous shenanigans, or that it “wasn’t really a gold standard system.” Sorry, it was.

We will look more closely at how the Federal Reserve operated during those years soon.