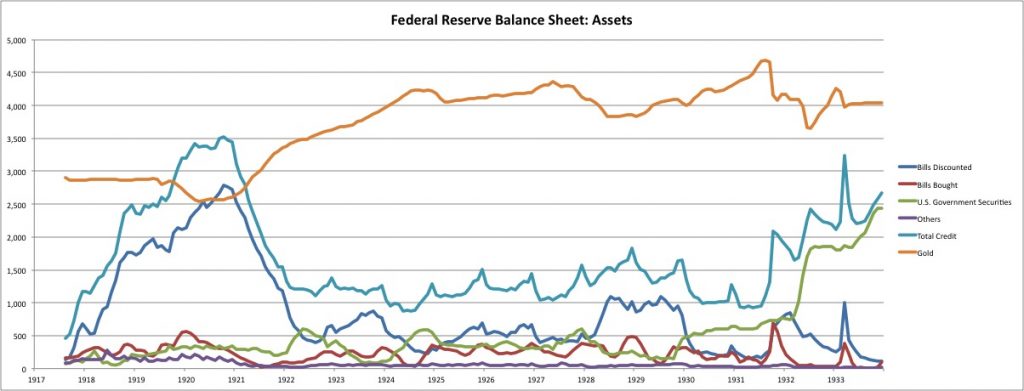

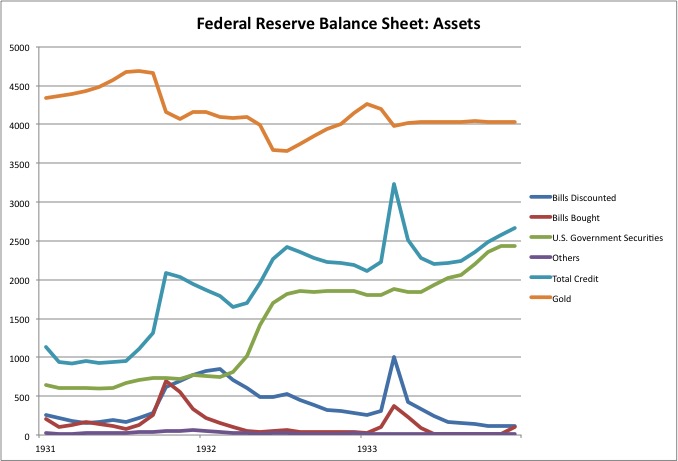

Today we will be looking a little more closely at the Federal Reserve’s bond-buying experiment of 1932. The Federal Reserve came under considerable political pressure that they “weren’t doing anything” or in one way or another should address the problems of the day with more money-creation. To resolve any such contentions, the Federal Reserve undertook the purchase of about $1,000 million of government bonds. Here’s what it looked like:

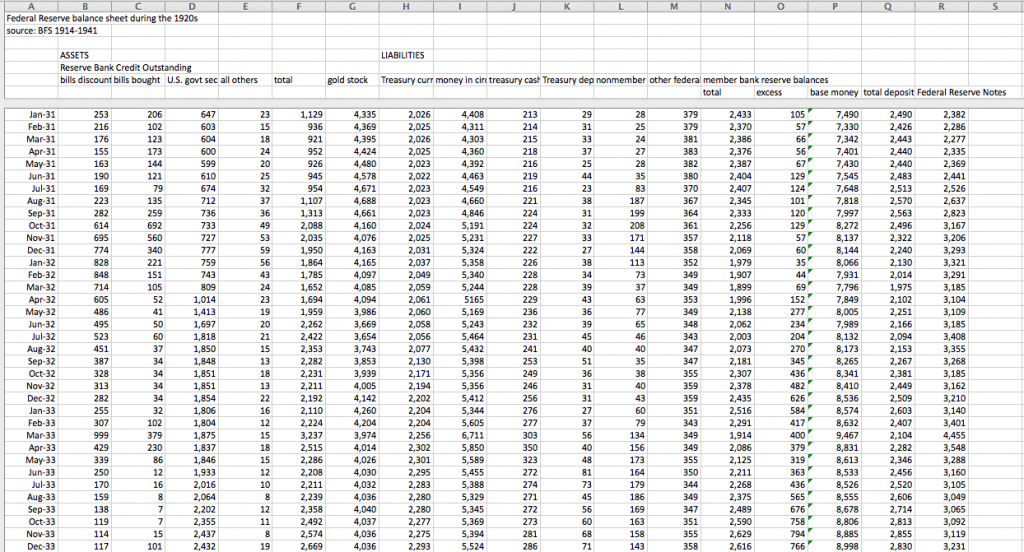

As you can see, government securities makes a big jump over three months in 1932. This was offset by outflows of gold and also a big reduction in “bills discounted.” The overall effect was this:

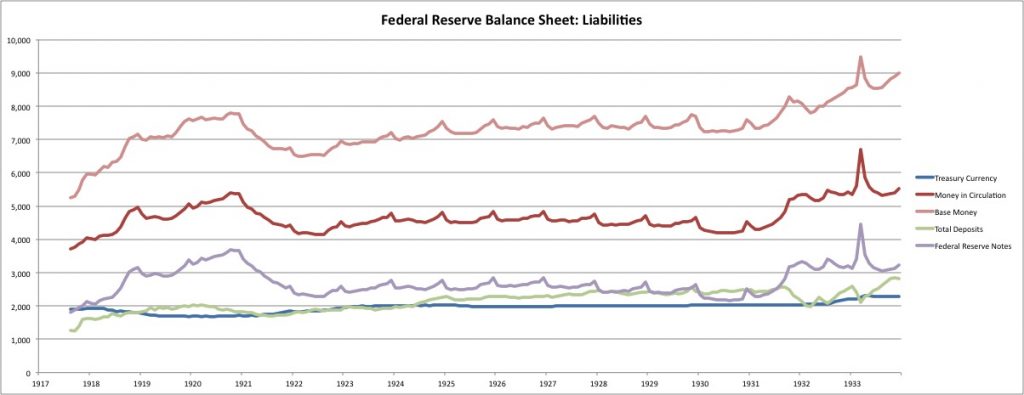

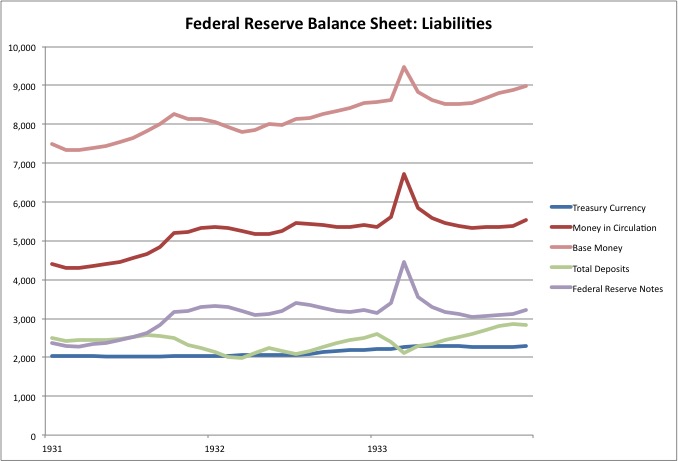

We can see that there was a modest rise in base money in 1932. However, this rise was largely independent of the Federal Reserve’s bond-buying splurge. It began around the beginning of 1931, and continued throughout 1932. Indeed, 1932 shows a very smooth, even rise (taking into account seasonal factors), with nary a discernible ripple caused by the government securities purchases, which were compressed into a three-month window. I interpret this to show that the demand for money was rising throughout this period, beginning around the start of 1931. To accommodate this increase in demand, within the context of the gold standard system, the Federal Reserve naturally increased supply — the smooth upward line. This increase in demand would have been satisfied whether the Federal Reserve purchased bonds or not. If no bonds at all were purchased, it would be satisfied either through other operations (primarily discounting and lending), or via gold inflows.

There was no overt effort to “sterilize” the bond purchases by equally offsetting reductions in other categories. Even if there were, we would not get this result, because there was actually a steady rise in base money, not a flatline.

I take this as some interesting evidence of just how little central banks were actually able to do from a discretionary standpoint. They were entirely constrained by the automatic systems of the gold standard, in particular gold bullion convertibility. The same was true of the increase in Fed Credit in 1927-28, which Murray Rothbard made a big deal about. It was perfectly and exactly cancelled by gold outflows, such that the smooth curve (with a seasonal pattern) of base money during that time shows no discernible effect at all. Not even a little ripple. I didn’t really expect the gold standard systems of that time to be so perfectly and exactly calibrated until I looked at this data closely.

January 31, 2016: Blame Benjamin Strong

The same was true of the contraction in Fed Credit in 1929 and 1930. This was offset by gold inflows, and base money was about as placid as anything can be, given the turmoil of the time. Thus, there was no “easy money” in 1927 or “tight money” in 1929. Whatever the intent of the changes in Fed Credit, it was all cancelled out.

I might mention that there was quite a lot of turmoil after September 1931, due to the devaluation of the British pound that month, and the subsequent devaluation of over twenty other currencies before the end of the year. After March 1933, gold conversion was suspended and the the dollar was devalued vs. gold. That’s why gold reserves flatline at that point.

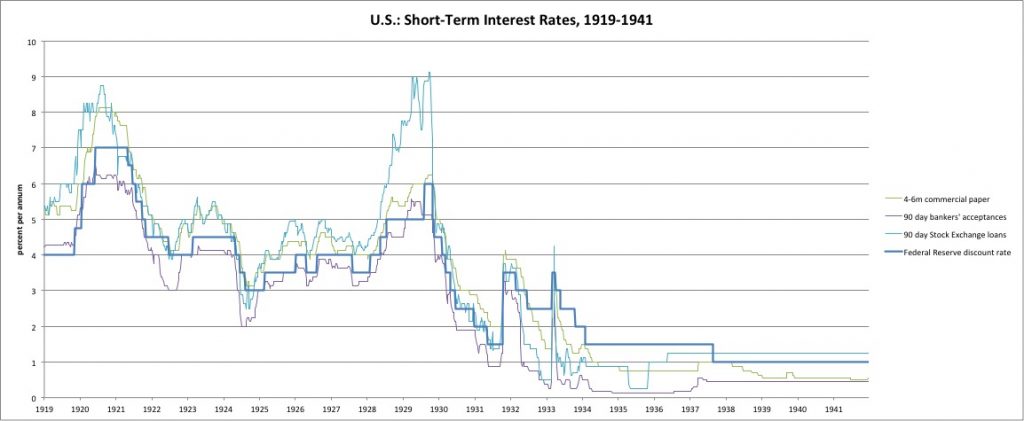

The flood of new base money that resulted from the bond purchases appeared, in the first instance, on banks’ balance sheets. Banks then found they had more bank reserves (Fed deposits) than they wanted, so they paid back their discounts and loans from the Fed. Market rates fell below the discount rate, which is why discounting and lending contracted.

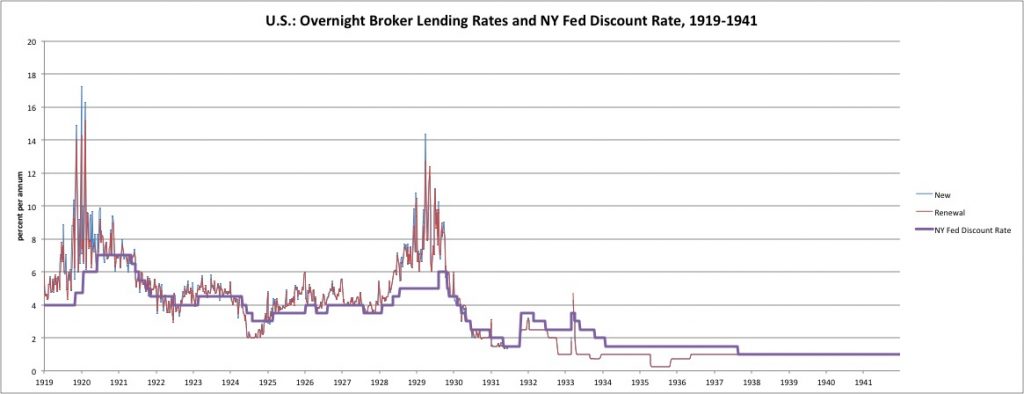

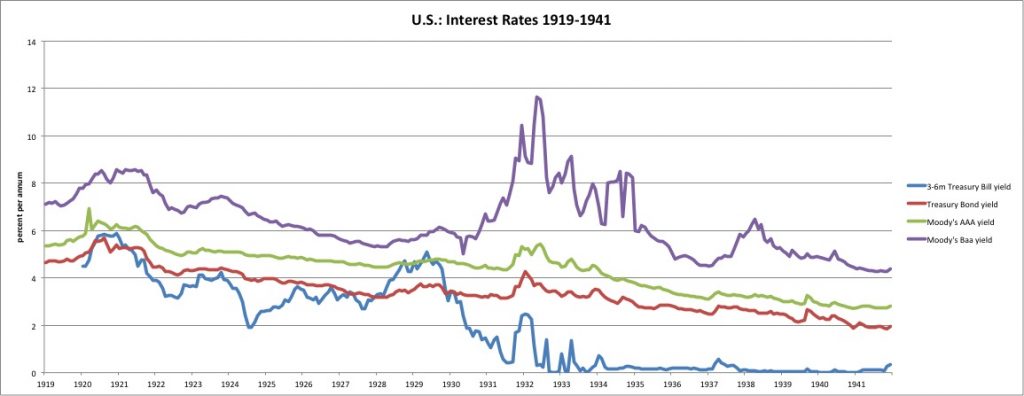

I wanted to take a little closer look at that time period, and also put it in a little historical context. Here is what it looks like up close:

Next week, we will look at things from more of a historical perspective.