The Flat Tax in Russia

May 30, 2010

Today we are archiving a series of blog posts by Alvin Rabushka, an economist at Stanford who has been a flat-tax advocate from the olden days when the only such example in the world was Hong Kong. His book The Flat Tax was first published in 1985.

Russia was the first large country to adopt a flat tax system, with at 13% rate legislated in 2000 and implemented in January 2001. Here is how it turned out. I’ll list Alvin’s notes in chronological order. I put the most interesting bits in boldface so they are easy to find.

http://flattaxes.blogspot.com/

This is a wonderful example of the Magic Formula, which is Low Taxes and Stable Money. Can you see why I suggest a 19% VAT-only system for Greece (a 15% flat tax would be fine too, but why be a copycat) — right here, right now, combined with a default and restructuring of past debts?

December 10, 2006: The Magic Formula

May 9, 2010: The Two Santa Claus Theory

May 2, 2010: Thoughts on Greece

February 14, 2010: The Problem with Greece

Remember, Russia defaulted on its dollar-denominated debt in 1998. In 2000, the debt was restructured with a 50% haircut. Today, Russia’s debt/GDP ratio is about 6%.

Don’t make me get my purple dinosaur.

January 18, 2009: “Austerity” and “Stimulus” 2.0

Lastly, at the end, I attached an update on what happened in the first year after Albania (adjacent to Greece) adopted a 10% flat tax. Pretty much the same result. I always hear about how Russia’s success was due to “rising oil prices,” which mysteriously had little effect on Iran or Nigeria. These figures are for personal income taxes, not total taxes. Also, revenues had huge gains in 2001 and 2002, while oil prices were basically flat.

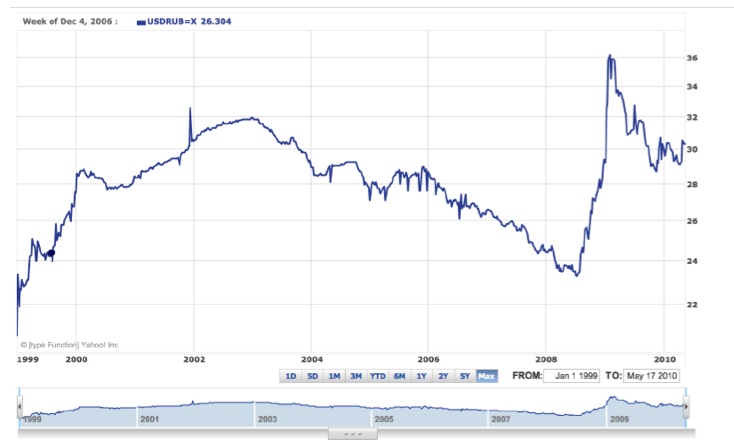

Stable Money was another part of Russia’s success since 2000. The ruble has been basically flat against the dollar during that period, going from 29/dollar at the beginning of 2001 to 30/dollar today.

This followed a period of rather harsh inflation. The 1989-1995 period had hyperinflation during which the ruble’s value fell by a factor of about 1000:1. The ruble was stabilized against the dollar somewhat from 1995-1998, but collapsed again during the crisis of 1998, in which Russia defaulted on its dollar-denominated debt. The ruble’s value fell by an additional factor of about 5:1 before being stabilized in 2000. I might note that the flat tax plan, which was passed in mid-2000, probably did a lot to help stabilize the ruble as well. Big tax cuts tend to be currency-supportive.

September 30, 2007: Taxes and Money

Thus, the immense gains in nominal revenue (and workers’ salaries) during the 2001-2007 period represents in part a correction from past inflations. Basically, Russians had become very, very poor due to a decade of economic disaster. Wages were extremely low, in U.S. dollar terms, as were prices for just about everything. The “inflation” during the 2001-2007 period was not a matter of the currency losing value (except to the extent that the dollar and all other currencies lost value vs. gold during that period), but mostly a matter of Russian prices rebounding from super-depressed levels, on top of genuine new wealth creation during that period. Similar to the “inflation” of the 1980s in the U.S.

The revenue from the 13% flat income tax in 2007, of 1,267 billion rubles, was 624% higher than revenue of 175 billion rubles in 2000. Remember, during this time the ruble was about stable vs. the dollar, so the gains were not “inflationary” in that sense.

Albania is not starting from such a devaluation-depressed level, so the results are not quite so dramatic. But they are still very good, as you will see.

I was talking to a Russian friend of mine in 2005. He had an advanced degree in nuclear physics — and Russian nuclear physicists are among the best in the world — but worked on Wall Street. “Russia is not an emerging market,” I told him, “it is an industrial economy that suffered a disaster, like Germany after World War II.”

If Russia sticks with the Magic Formula, it will become wealthier than Germany in a couple decades. Of course, a reliable gold-linked ruble would really kick the Magic Formula into high gear. Moscow would become the world’s financial capital.

Lastly, it appears that we need a graduate student to go and figure out what has happened in all of these countries (about 25 so far) that have followed Russia’s lead and adopted a flat tax system. That would make a fine Ph. D. dissertation and a book. Contact Alvin Rabushka at Stanford. If you are in a philanthropic mood, you might even consider funding a graduate student. Once again, contact Alvin Rabushka, who is the go-to guy for all things flat tax.

February 7, 2010: Ibn Khaldun, Taxes, and the Rise and Fall of Empires

January 17, 2010: The Futility of Raising Taxes

June 30, 2007: East Europe’s Flat Tax Revolution

August 9, 2009: Recommended book: For Good and Evil — the Impact of Taxes on the Course of Civilization

August 5, 2008: Tax Cuts are the Solution to Everything

September 14, 2008: Depression Economics

November 24, 2008: Russia’s Currency Crisis

November 23, 2008: Redeemability and Reserves

November 16, 2008: How To Stabilize the Ruble

May 24, 2008: Japan: Silly Self-Destructive Behavior

May 18, 2008: Japan: Tax Hikes are No Fun

June 24, 2007: The Gold Standard in a Nutshell

Russia Adopts 13% Flat Tax

July 26, 2000

By Michael S. Bernstam and Alvin Rabushka

International organizations and experts have blamed Russia’s economic woes on its failure to collect taxes. They have urged the Russian government to make tax reform a high priority.

The Russian government, under its new president, Vladimir Putin, has made tax reform its number one economic policy priority. It sought approval for several tax reform measures from the Duma (lower house of the Russian parliament) and Federation Council (upper house) before their mid-summer recess. On July 26, 2000, the Federation Council voted 115-23, with five abstentions, to approve the government’s several tax reform proposals. On July 19, 2000, the Duma had already approved, by a 234-111 vote, these reforms. The object of the tax reform was to simplify the tax code and reduce the tax burden on the Russian people.

Among the tax reform measures is a 13% flat tax on personal income, which replaces the previous three-bracket system with a top rate of 30%. The new flat tax is intended to achieve greater compliance due to its simplicity and low rate. The New York Times, in its editorial of May 28, 2000, praised President Putin’s 13% flat-tax plan: It would reduce corruption, remove subsidies from favored constituents, raise the money to pay for badly-needed services, and establish the credibility to push for further reforms. A viable tax system, said the Times, would allow the Russian government to deal with a failing health system and poverty.

Other tax reforms include reducing the turnover tax rate, a unified social tax and lower social insurance tax rate (replacing previously separate taxes for pensions, social insurance, medical insurance, and unemployment), elimination of most small nuisance taxes and tax privileges, and a reduction in customs duties.

Russia is not the first so-called transition economy to enact a flat tax. Estonia implemented a flat tax on January 1, 1994; in 1999, it further eliminated the corporate profits tax on retained earnings, thereby achieving a single flat tax on business cash flow. On January 1, 1995, Latvia implemented a flat tax similar to that of Estonia. Russia’s adoption of a flat tax brings to three the number of former Soviet economies that have embraced this concept.

Despite the defeat of Steve Forbes in the Republican Party primaries, the concept has gained new currency in North America. The Canadian Alliance, Canada’s official opposition formed from the merger of two Western parties and the remnants of the Ontario-based Progressive Conservative Party, has made a 17% flat tax the centerpiece of its campaign to unseat the Liberal Party in the national election likely to take place next summer. Mr. Stockwell Day, head of this party and former treasurer of Alberta, has already achieved a 10.5% provincial flat tax in Alberta, the first flat tax in any of Canada’s provinces.

The new Russian tax law is scheduled to take effect on January 1, 2001.

The Flat Tax at Work in Russia

February 21, 2002

By Alvin Rabushka

On March 25, 1981, I first proposed the idea of a flat tax on the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal in an article entitled “The Attractions of a Flat-Rate Tax System.” Later that year, on December 10, 1981, Robert E. Hall and I set forth the mechanics of a specific flat tax proposal in an article entitled “A Proposal to Simplify Our Tax System.” Twenty years later, the flat tax has become a reality in, of all places, the Russian Federation.

Since the emergence of the Russian Federation a decade ago, taxpayer compliance has been a problem. To help resolve this problem and improve incentives, the Russian government enacted in July 2000 a 13% flat-rate tax on personal income. It took effect on January 1, 2001, replacing the previous three-bracket system, which imposed a top rate of 30% on taxable income exceeding $5,000. President George W. Bush praised Russia’s flat tax in each of his meetings with President Vladimir Putin, most recently during their November 15, 2001, press conference held at Crawford High School.

A year has passed since its implementation, which provides an opportunity to evaluate its success.

From a revenue standpoint, the 13% flat tax has exceeded all expectations. Preliminary data for 2001 reveal that the flat tax generated R254.7 billion, an increase of R80.2 billion over 2000, up 46%. ($1 = R30.8) Adjusting for ruble inflation of about 18% during 2001, real ruble revenues increased about 28%. Personal income tax, which contributed 12.1% to consolidated budget revenues in 2000, amounted to 12.7% in 2001. Since economic growth in 2001 of 5.2% was lower than the record 8.3% growth in 2000, the substantial rise in personal income tax revenue cannot be attributed solely, or even largely, to last year’s growth, but rather to the tax reform itself.

It is estimated that 60 million Russian employees receive salaries or wages subject to personal income tax. In tax year 2000 (the deadline for filing was May 3, 2001), only 2.8 million individuals filed tax returns. This small number is due to the fact that, for most employees, income tax is calculated and withheld monthly by employers and remitted directly to the Russian Treasury. Individuals need not file a return unless they owe additional taxes from other sources of income or seek a refund because of special deductions or credits.

Sole proprietors can choose to pay imputed income tax instead of filing a tax return. In tax year 2000, some 1.336 million individuals chose this option, which also reduces the number of returns.

Before examining the tax form itself, it should be noted that the new tax includes two higher brackets. Dividends are taxed at 30%. However, double taxation on corporate income has been abolished. Since the corporate tax rate fell from 35% in 2001 to 24% on January 1, 2002, it is likely that the tax on dividends will be lowered in the future. In addition to dividends, foreigners and Russians who reside in Russia less than 183 days during the tax year are taxed at a rate of 30% on their taxable income. Other sources of income (e.g, lotteries) are taxed at 35%. The higher rates on dividends and other sources of income reflect a Russian distinction between so-called “unearned income” and “earned income” (even though capital gains on homes and securities are exempt).

Russia’s basic flat tax form, Form 3, resembles U.S. Form 1040A, with one addition. Form 3 is used to report income from wages and salaries (Form 1040A), along with professional income (Schedule C). For most taxpayers, required information can be reported on Form 3. Individuals with self-employment and other sources of income, and/or who are able to itemize specific deductions, may need to attach several supplementary schedules. Altogether, taxpayers can attach up to 10 supplementary schedules (A, B, V, G, D, E, Zh, Z, I, and K—the Russian alphabetical order transliterated according to the Library of Congress convention). For a small number of taxpayers, the Russian individual tax return is more complicated to file, closer to Form 1040. Some Russians will likely avail themselves of the Russian version of H & R Block. The tax form recognizes this complexity by including space for the signature of a professional tax preparer.

Form 3 is only two pages long. The first page includes the taxpayer’s name, taxpayer identification number, details of a photo ID, period of residence and citizenship (for foreign nationals), permanent address, and number of supplementary documents. Page 2 of form three on which financial data are reported consists of 5 sections. Sections I through IV contain 13 lines on which salaried employees and small business owners, or sole proprietors, report their income from all sources, expenses, allowable deductions, tax credits, and other pertinent items. Section V contains 4 lines that apply to self-employed professional persons for reporting estimated income on a quarterly basis (Form 1040-ES).

Here is the information that the taxpayer must report line by line.

Section I. Tax base (income) which is taxable at a 13% rate.

1. Wages, salaries, and small business income (gross income)

2. Total deductions (transferred and added from lines V3.2, G1.5, G2.6, D1.1, D2.1, E.4, Z3.6, and Z3.7 as described below)

V3.2: Total expenses related to individual entrepreneurship and private practice (small business expenses as reported on Schedule C)

G1.5: A deduction of up to R2000 for each the following types of partially taxable income (cash allowances from employer to retired employees due to age or disability, gifts that are exempt from the gift and inheritance tax, prizes in cash or kind won in contests sponsored by the government or a legislative body, and employer reimbursement of prescribed pharmaceuticals—total limit of R8000 from all four categories)

G2.6: Deductions from the sale of real property and financial assets. Deduction for housing and land owned less than five years is limited to documented costs up to R1 million; deduction for housing and land owned more than five years is unlimited. For non-financial real property owned less than three years, deduction is limited to R125,000; for non-financial real property owned more than three years, deduction is unlimited. For gains on the sale of financial assets, deduction is unlimited (capital gains reported on Schedule G)

D1.1: Expenses incurred in the production of income received from honoraria, publications, patents, and copyrights (reported on Schedule E)

D2.1: Expenses incurred in the production of income from contractual services under civil-law contracts (reported on Schedule C relating to Form 1099 Misc.)

E.4: Calculation of standard deduction (equivalent to personal exemptions). For example, R3000 per month for victims of nuclear disasters and disabled servicemen; R500 per month for other victims of war and radiation sickness; R400 per month for all other taxpayers until annual income exceeds R20,000; and R300 per month for each child under 18 years of age until the child’s parent or guardian’s income exceeds R20,000 in any tax year. Calculation of social deductions (equivalent to itemized deductions): for charitable contributions (limited to 25% of total revenue); self-financed education (limited to R25,000); children’s education (limited to R25,000 per child); medical and drug expenses (limited to R25,000);and catastrophic medical expenses (unlimited). Social deductions are granted only after the return is filed.

Z3.6: Expenses supported by documents for purchase and/or new construction of residential housing in 2001 (limited to R600,000) This excludes summer homes, or dachas.

Z3.7: Mortgage interest deduction on residential housing in 2001 (unlimited) Excludes summer homes, or dachas.

3. Calculation of tax due to be remitted from consolidated annual income (total taxable income), line 1 minus line 2.

4. Tax due: line 3 times 13%

II. Tax base which is taxable at a 30% rate

5. Total dividends (Schedule B); income of non-residents in Russia (less than 183 days)

6. Offsets (tax withheld by payer of dividends and remitted on behalf of recipient)

7. (Line 5 times 30%) minus line 6.

III. Tax base, which is taxable at a 35% rate.

8. Other income. Sources include: (1) gains and prizes from contests and games for the purpose of advertising, (2) winning of lotteries and pari-mutual bets, (3) net insurance receipts (4) bank taxable interest; and, (5) gains from loans at below-market rates.

Bank interest is taxable (1) when interest on ruble deposits exceeds 75% of the Central Bank’s refinancing rate, or (2) on foreign currency deposits if annual interest exceeds 9%. Material gains from borrowing are taxable if interest charged is below 75% of the Central Bank’s refinancing rate or below 9% if in foreign currency.

These adjustments amount to a proxy for inflation. The current Central Bank refinancing rate is 25%. Three-quarters of that is 18.75%. Most deposits earn less than 18.75%, which means that interest income is not generally subject to taxation.

9. Tax due (line 8 times 35%).

IV. Calculation of total amount of tax due from all sources of income

10. Sum of lines 4, 7, and 9 (total tax due)

11. Withheld taxes and estimated tax payments (total taxes paid)

12. Refund due

13. Additional tax due

V. Calculation of estimated income and estimated tax for private entrepreneurs, public notaries, and those in private practice.

14. Total estimated income (determined by taxpayer)

15. Total withholding, according to Articles 2.18 and 2.21 of the tax code

16. Total estimated taxable income

17. Total advance income tax payments

Lines 15, 16, and 17 are filled in by the tax authorities.

Russia’s personal income tax excludes income from a large number of sources. Examples include public welfare for the disabled and children, state pensions, alimony, grants received for development of science, education and art, compensation for natural disasters, enterprise-provided medical services, stipends to students, proceeds of part-time farming (food grown at dachas), income from amateur hunting, athletic prizes, interest on government debt, capital gains on government bonds, military pay, recipients of payments from labor-union sponsored athletic and cultural events, and others.

To summarize, the 13% flat tax has exceeded the expectations of the government in terms of revenue. For the vast majority of taxpayers, its implementation is simple and no forms need be filed. For small businesses, the 13% flat tax provides strong incentives and compliance is straightforward. Small wonder that President Bush had a gleam in his eye when he praised Russia’s flat tax. Perhaps he might take a lesson from President Putin as he considers his campaign themes for 2004.

(Anjela and Diana Kniazeva, graduate students at Stanford University, provided research assistance for the preparation of this article.)

Improving Russia’s 13% Flat Tax

March 11, 2002

By Alvin Rabushka

On February 21, 2002, I posted to this site an article entitled “The Flat Tax at Work in Russia.” In that article, I pointed out an anomaly in Russia’s 13% flat tax, namely, there are two sources of income that are taxed at higher rates. The first source is dividends and the income of non-residents, which are taxed at 30%. The second consists of five different kinds of income, which are taxed at 35%. These are (1) gains and prizes from contests and games for the purpose of advertising, (2) winnings of lotteries and pari-mutual bets, (3) net insurance receipts, (4) bank taxable interest, and (5) gains from loans at below-market rates. As mentioned in “The Flat Tax at Work in Russia,” for all practical purposes, the latter three kinds of income are either lightly taxed or not taxed at all.

There is, in my view, no apparent reason for these two higher rates, especially the 35% rate, which serve only to complicate the simplicity and administration of Russia’s otherwise transparent 13% flat tax.

In apparent agreement with this view, the Russian government is currently preparing a Bill on Lotteries that would reduce the 35% tax rate on lotteries to the standard flat rate of 13%. (See http://www.rbcnews.com/free/20020307152617.shtml) The organizer of a lottery would have to pay 10% of the profit derived from the lottery after deducting all expenses and awarding prizes. The bill will define lotteries aimed at the promotion of specific goods on the market as a kind of lottery and taxed at 13%.

It will be worth watching the Russian government in the coming months to see if it continues to simplify its flat tax on personal income by dropping the remaining kinds of income taxed at the third rate. The reduction in the corporate tax rate from 35% to 24%, which took effect on January 1, 2002, should also prompt the government to reduce that 30% tax rate on dividends in the near future.

Further Extending Russia’s Tax Reforms

April 1, 2002

By Alvin Rabushka

The Russian government is in the process of further extending its tax reforms. A first step was the introduction of a 13% flat tax on personal income (see “The Flat Tax at Work in Russia” and “Improving Russia’s 13% Flat Tax”), which took effect in 2001. Second, it reduced the corporate tax rate from 35% to 24%, beginning January 1, 2002.

Now the Russian government is planning to simplify and reduce the tax burden on small businesses. Under the current proposal put forth by the Russian government, a small business is defined as having no more than 20 staff and annual turnover under R10 million (about $322,000 at the current exchange rate). The proposal would grant small businesses a choice between a 20% flat tax on profits or an 8% flat tax on revenues, whichever is lower, beginning January 1, 2003 (assuming Duma approval, which appears likely). This small business tax rate on profits partially splits the difference between the higher 24% corporate rate and the 13% personal rate.

Other changes in the tax treatment of small businesses will accompany the reduction in rates. Collection of the small business tax will shift from a monthly to quarterly basis, mirroring the reporting of estimated taxes for private entrepreneurs and professionals in the personal income tax. Accounting for tax purposes will change from an accrual to cash basis; taxes will no longer be collected on imputed or phantom income. Finally, small businesses will be able to expense their outlays on capital assets in place of the current depreciation system (along the lines of the Section 179 expensing provision in the U.S. Internal Revenue Code). These changes are expected to reduce accounting costs for small business enterprises.

The plan also exempts small businesses from value-added tax, sales tax, property tax, and social insurance taxes.

Assuming some version of this small business tax reform proposal is enacted by the Duma this year, Russia will have completed a major overhaul of its personal, corporate, and small business taxation within the short span of three years. Some opportunity for further simplifying the personal income tax remains (see “Improving Russia’s 13% Flat Tax”), especially reducing the 30% tax rate on dividends now that the corporate profits tax rate has been cut to 24% and there is no capital gains tax on the sale of Russian equities.

Tax Reform Remains High on Russia’s Policy Agenda

May 22, 2002

By Alvin Rabushka

On April, 2002, I posted to this site an article entitled “Further Extending Russia’s Tax Reforms.” It described the Russian government’s new proposal to radically simplify and reduce the tax treatment of small businesses. Under the plan, small business firms could choose to remit the lesser of a 20% flat tax on profits or an 8% flat tax on revenues. Firms that qualify—those with no more than 20 staff and turnover under R10 million ($320,000)—would also be exempt from value-added tax, sales tax, property tax, and social insurance taxes.

Thus far, Russia’s 13% flat tax on personal income (see “The Flat Tax at Work in Russia”), which took effect in 2001, has met its two major objectives of improving incentives and compliance. Building on it, the Russian government reduced corporate income tax rates from 35% to 24% in 2002. On May 21, 2002, the government further enhanced its small business proposal.

It widened the definition of a small business to include firms with turnover up to R15 million ($469,000), a 50% increase over the initial proposal of a few months ago. Small business firms could choose to remit the lesser of a 15% flat tax on profits or a 6% flat tax on turnover.

Note that the 15% flat tax on small business profits is close to the 13% flat tax on personal income, which encompasses sole proprietors. By reducing the 20% rate to 15%, the Russian government will make it easier in the future to equalize the tax treatment of small business income, eliminating the distinction between sole proprietor and small firms of 2-20 employees.

Completing Small Business Tax Reform

July 3, 2002

By Alvin Rabushka

On July 2, 2002, the Duma, the lower house of the Russian Parliament, concluded its business prior to the start of its summer vacation. Among the bills approved was a comprehensive reform of small business taxation. Once the measure is approved by the Federation Council, the upper house of Parliament, and signed by President Putin, the measure becomes law.

On May 22, 2002, I posted to this site an article entitled “Tax Reform Remains High on Russia’s Policy Agenda.” It described the government’s proposal. Small firms with fewer than 20 staff and turnover under R15 million ($477,100 at current exchange rates) could choose to remit the lesser of a 15% flat tax on profits or a 6% flat tax on turnover. Eligible businesses would enjoy exemption from value-added tax, sales tax, property tax, and social insurance taxes.

The measure approved by the Duma on July 2 retained the previous provisions on tax rates and turnover, but extended the number of employees in any eligible small business to 100. The benefits of qualifying as a small business are readily apparent since larger corporations are subject to a 24% profits tax.

We have commented on this site on all of Russia’s major tax reforms, especially the 13% flat tax on personal income (see “The Flat Tax at Work in Russia” and The Flat Tax). The personal income tax has been especially productive of revenue, with ruble receipts up 28% in real terms in 2001 compared with 2000.

On July 1, 2001, the senior deputy minister of finance reported that underpaid taxes to the federal budget in the first half of 2002 amounted to R 17 billion ($540.17 million). He acknowledged that collection of tax on the extraction of natural resources, income tax for individuals, and the unified social tax was satisfactory, but that the collection of value-added taxes and profits taxes was below projections. (See www.rbcnews.com/free/20020701140045.shtm) The reasons for the new small business tax are to improve incentives and compliance among these firms. With exemptions from value-added tax, sales tax, property tax, and social insurance taxes, small businesses will receive a substantial reduction in their tax burdens. Banking, insurance, and investment businesses are excluded from the small business tax reform.

Where can Russian tax reform go from here?

Additional simplification can be achieved by reducing the small business profits flat tax rate to 13%, which would eliminate the unnecessary distinction between sole proprietors and small businesses.

A more drastic measure would reduce the corporate income tax rate from 24% to 13%, thereby permitting full integration with the personal and small business taxes. This would enable all taxpaying entities to be treated equally in terms of the choice of legal ownership.

If it were necessary to maintain revenue neutrality, the government could raise the value-added tax by a few percentage points, or impose a higher natural resource extraction tax.

Recent rate reductions and simplifications have transformed a complex, high-rate tax system into a simpler, low-rate system. A few additional measures could complete the process of tax reform.

The Flat Tax at Work in Russia: Year Two

February 18, 2003

By Alvin Rabushka

On January 1, 2001, a 13% flat-rate tax on personal income took effect in Russia. (On the general principles and beneficial economic effects of the flat tax, see The Flat Tax.) Russia’s 13% flat tax replaced a three-bracket system, which imposed a top rate of 30% on taxable income exceeding $5,000.

During its first year, the 13% flat tax exceeded all expectations. In 2001, personal income taxes increased 46% in nominal rubles, or 28% in real rubles after adjusting for ruble inflation of 18%. Personal income tax as a share of consolidated budget tax revenue rose from 12.1% in 2000 to 12.7% in 2001. Since economic growth of 5.0% in 2001 was lower than the record 9.0% growth in 2000, the rise in revenue cannot be attributed solely, or even largely, to growth in 2001. For a detailed treatment of Russia’s 13% flat tax, see “The Flat Tax at Work in Russia.”

Data for 2002 are now available, posted to the Russian government’s Ministry of Finance web site. (Http://www.nalog.ru) Personal income taxes in 2002 amounted to R357.1 billion ($1=R31.7), up from R255.5 billion in 2001, an increase of 39.8%. Annualized average ruble inflation in 2002 was 15.8%. Thus, real ruble tax revenues rose 20.7%, another large increase. Moreover, economic growth of 4.3% in 2002 was lower than the 5.0% growth the previous year. Real ruble revenues continued to rise in 2002 despite slowing growth, suggesting greater compliance and efficiency in tax administration.

Since the implementation of Russia’s flat tax, personal income taxes have contributed a growing share of Russia’s consolidated budget. In 2002, the flat tax generated 15.3% of total tax revenue, up from 12.7% in 2001. From relative unimportance as a source of revenue a few short years ago, the 13% flat tax on personal income now exceeds excise taxes and taxes on natural resource use, and is fast catching up with corporate income tax and value added tax.

To date, the governments of Estonia, Latvia, and Russia have enacted flat-rate taxes on personal income. Russia has also implemented a reduction in the corporate rate of tax, from 35% to 24%, effective January 1, 2002. Russia has also enacted a flat-rate small business tax, the lesser of 6% of gross turnover or 15% of profits. (See “Further Extending Russia’s Tax Reforms,” “Tax Reform Remains High on Russia’s Policy Agenda,” and “Completing Small Business Tax Reform”) A Chinese edition of The Flat Tax is scheduled for publication by China’s Ministry of Finance in early 2003.

(Anjela and Diana Kniazeva, graduate students in the Department of Economics, Stern School of Business, New York University, provided research assistance for the preparation of this article.)

The Flat Tax at Work in Russia: Year Three

April 26, 2004

By Alvin Rabushka

On January 1, 2001, a 13% flat-rate tax on personal income took effect in Russia. (The general principles and beneficial economic effects of the flat tax appear in The Flat Tax.) Russia’s 13% flat tax replaced a three-bracket system, which imposed a top rate of 30% on taxable income exceeding $5,000. The flat tax has been remarkably successful by every conceivable measure, and has encouraged such other countries as Serbia (2003), Ukraine (2004), and Slovakia (2004) to implement flat taxes of their own. Political parties in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Georgia have announced their support for the flat tax and there is interest in Bulgaria and Romania. Even China has taken the step of translating The Flat Tax into Chinese for consideration by the Ministry of Finance.

Let’s review Russia’s 13% flat tax since its implementation on January 1, 2001. In 2001, personal income tax (PIT) revenue totaled R255.5 billion, an increase of 46.7% in nominal rubles, or 25.2% in real rubles after adjusting for inflation of 21.5%. PIT revenue as a share of consolidated budget tax revenue rose from 12.1% in 2000 to 12.7% in 2001. Since economic growth of 5.1% in 2001 was lower than the post-Soviet record 10.0% growth in 2000, the rise in revenue cannot be attributed solely, or even largely, to growth in 2001. (For a detailed treatment of Russia’s 13% flat tax, see “The Flat Tax at Work in Russia.”)

In 2002, PIT revenue amounted to R357.1 billion, an increase of 39.7% over 2001. After adjusting for inflation of 15.1%, real revenue rose 24.6%, supplying 15.3% of the consolidated budget. GDP growth in 2002 was 4.7%, a small decline over 2001. (See “The Flat Tax at Work in Russia: Year Two.)

In 2003, PIT revenue generated R449.8 billion, a nominal gain of 27.2% over 2002. After adjusting for inflation of 12.0%, real revenue increased 15.2%, supplying 17% of consolidated budget revenue. GDP growth in 2003 was a more robust 7.3%. Only corporate income tax and value added tax generated more revenue than the PIT.

The composition of PIT revenue in 2003 was as follows: taxes assessed on income at the 13% rate generated 96.9% of all PIT revenue; taxes on dividends, assessed at a higher 30% rate, 1.9%; and taxes on non-residents and individual entrepreneurs, 0.9%.

In the three years since the top rate of PIT was reduced from 30% to 13%, real flat tax revenue has risen by 79.7%. Russia’s budget is relatively healthy. Tax compliance has improved. And incentives to work, save, and invest remain strong.

(Anjela and Diana Kniazeva, graduate students in the Department of Economics, Stern School of Business, New York University, provided research assistance for the preparation of this article.)

The Flat Tax at Work in Russia: Year Four, 2004

January 26, 2005

By Alvin Rabushka

On January 25, 2005, the Ministry of Taxation of the Russian Federation reported total taxes and revenues for the consolidated federal and regional budgets for 2004. The data show that the 13% flat tax on personal income continues to achieve very positive results.

In 2004, the ministry collected 574.1 billion rubles ($1 = R28) in personal income tax receipts, an increase of 26.1% over 2003. After adjusting for annualized consumer price inflation of 11.7% in 2004, real personal income tax revenue rose 14.4%. This growth builds on real ruble revenue increases of 25.2% in 2001, 24.6% in 2002, and 15.2% in 2003. For the four years, compound real ruble revenue increased 105.6%.

The 26.1% nominal growth in personal income tax receipts outpaced the overall 24.7% rise in total taxes and fees in 2004. As a share of total taxes and revenue, it rivals payments for use of natural resources, is more than double excises, and now stands at 76.6% of value added tax. The most dramatic change in 2004 is the 64.5% rise in nominal rubles, or 52.8% in real rubles, in corporate taxes. This is due to stepped up enforcement, exemplified in Yukos and other corporate cases, which has produced a new enthusiasm among corporate heads for compliance.

Consolidated tax receipts are divided between the federal and regional budgets. Personal income tax revenue is allocated entirely to regional budgets. It now supplies 31.9% of regional revenue, making regional governments the main beneficiaries of the 2000 personal income tax reform.

The Flat Tax at Work in Russia: Year Five, 2005

May 11, 2006

By Alvin Rabushka

The Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation has reported provisional data for total taxes and revenues for the consolidated federal and regional budgets for 2005. The data show that the 13% flat tax on personal income continues to achieve very positive results.

In 2005, the ministry collected 707 billion rubles ($1 = R27) in personal income tax receipts, an increase of 23.1 percent over 2004. After adjusting for annualized consumer price inflation of 10.95% in 2004, real personal income tax revenue rose 10.9%. This builds on real ruble revenue increases of 25.2% in 2001, 24.6% in 2002, 15.2% in 2003, and 14.4% in 2004. Total real ruble revenue has increased 128 percent (more than doubled) in the five years since the 13% flat tax was implemented. It should be recalled that top marginal rate in 2000 was 30% before the implementation of the 13% flat tax on January 1, 2001. The low flat rate contributed to the decline in capital flight, improved taxpayer compliance, and increased revenue. To further the culture of compliance, several prominent Russians have been jailed on charges of tax evasion.

Other tax revenues have shown even healthier increases. In real ruble terms, after adjusting for inflation, corporate profits taxes rose 38.4%, value added taxes, 24%, taxes, dues and regular payments for the use of natural resources (severance tax), 44.4%, and taxes on external trade and foreign economic operations, 78.3%. The high price of oil and other natural resources accounts for the rapid growth in tax revenues from corporations, value added taxes, severance, and external trade. The remaining categories of excises, property taxes, and the single social tax declined.

The 13% flat tax has become a stable feature of Russia’s tax system. With the rise in real incomes percolating through the economy, receipts continue to grow at a healthy clip.

The Flat Tax at Work in Russia: Year Six, 2006

December 13, 2007

By Alvin Rabushka

The Federal Treasury of the Russian Federation has compiled the data for total taxes and revenues for the consolidated federal and regional budgets for 2006. The data show that the 13% flat tax on personal income continues to achieve very positive results.

In 2006, the Treasury collected 930.4 billion rubles ($1=RUB24.4) in personal income tax receipts, a nominal increase of 31.6% over the 707 billion rubles in 2005. After adjusting for annualized consumer price inflation of 9.0% in 2006, real personal income tax revenue rose 22.6% in 2006. Total real ruble revenue has more than tripled in the six years since the 13% flat tax was implemented on January 1, 2001. It should be recalled that the top marginal rate in 2000 was 30% before the implementation of the 13% flat tax. The low flat rate has contributed to the decline in capital flight, improved taxpayer compliance, and increased revenue.

The 13% flat tax has become a stable feature of Russia’s tax system. With the rise in real incomes percolating through the economy, receipts continue to grow at a healthy clip.

The Flat Tax at Work in Russia: Year Seven, 2007

August 28, 2008

By Alvin Rabushka

The Federal Treasury of the Russian Federation has compiled the data for total taxes and revenues for the consolidated federal and regional budgets for 2006. The data show that the 13% flat tax on personal income continues to achieve very positive results.

In 2007, the Treasury collected 1,266.6 billion rubles ($1=RUB24.6) in personal income tax receipts, a nominal increase of 36.1% over the 930.3 billion rubles in 2006. After adjusting for annualized consumer price inflation of 11.9% in 2007, real personal income tax revenue rose 17.8% in 2007. Total real ruble revenue has substantially more than tripled in the seven years since the 13% flat tax was implemented on January 1, 2001. It should be recalled that the top marginal rate in 2000 was 30% before the implementation of the 13% flat tax. The low flat rate has contributed to the decline in capital flight, improved taxpayer compliance, and increased revenue.

The 13% flat tax has become a stable feature of Russia’s tax system. With the rise in real incomes percolating through the economy, receipts continue to grow at a healthy clip.

The Flat Tax at Work in Albania: Year One

Beginning January 1, 2008, Albania implemented a 10% flat tax on corporate and personal income. The 10% personal rate replaced five rates that peaked at 30% while the 10% corporate rate was halved from the previous 20% rate. Despite the reduction in rates, total revenues increased from LEK 125 billion in 2007 to LEK 148 billion in 2008, an increase of 18.4%. ($1.00 = LEK 96.71). With inflation a modest 3% in 2008, real inflated-adjusted revenue rose 15.2%.

One other development in the flat tax world is worth noting. On January 1, 2009, Latvia’s personal income tax rate fell from 25% to 23%.