If you take an honest look at The Future, I think you have to conclude that it stinks. Most of the stuff in The Future is just plain idiotic.

I’m not talking about the real future. I’m talking about The Future — our collective image of what we supposedly want things to be like in our dreams.

The Future was Big Big Big in the 1920-1970 period. Since about 1970, we have become a little tired with The Future. We already know it stinks. Flying cars? Who needs it. Betcha the insurance is ridiculous. But, we haven’t replaced The Future yet with something better. We need a new vision of The Future. Right now, we are living in the mental rubble of an old, worn-out Future.

Let’s take a look at The Future. Here’s a splendid website that documents The Future, as it was imagined in the mid-20th century.

Food: Food in The Future is a chemical concoction made by scientists. It might even take the form of a pill! One uniform, scientific, factory-made product that provides everything your body needs. How simple! How clean! How convenient!

In The Future, humans eat dogfood.

Pill food from the 1930s.

Science Diet dogfood. You know, I bet this stuff isn’t even good for dogs. What did dogs eat before dogfood?

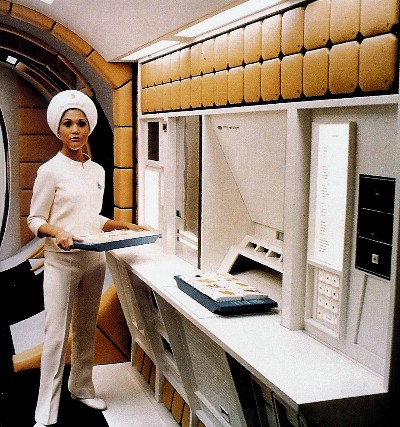

Mmmm … Tasty!

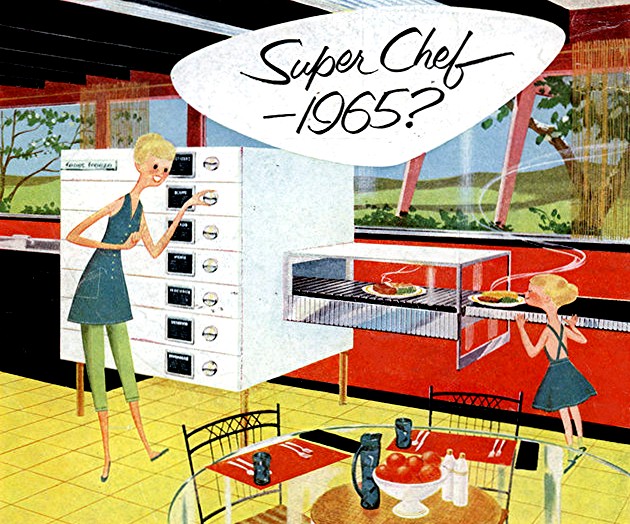

No more stoves and ovens … no more pots and pans … no more vegetables or meat or spices … no more cooking with food. Now our meals come out of our own private factory! With a conveyor belt — just like a real factory!

When you don’t cook anymore then you too can be a Super Chef!

Let’s see: chemical food that comes from a factory, made by scientists, that doesn’t involve any real cooking but merely pressing a button on the machine. That doesn’t describe the situation today at all.

Microwave dinner.

A Classic Favorite! Where’s my conveyor belt?

PowerBar Gel Step 2 Refuel 2x Caffeine with C2 Max higher-octane carb blend. Tangerine flavor.

The electrolytes of a sports drink! You can read about the science at Powerbar.com.

WTF is this?

Does it really contain more octane? (Octane is the primary hydrocarbon in gasoline.)

Bigger than a pill, admittedly. Gotta leave something for future generations to do.

For a while, I was road biking with a club in Connecticut. Some people brought stuff like this. After reading the ingredients, I figured out that apple juice would accomplish basically the same thing, was much better for your body, tasted better, and was a lot cheaper too. So, I put apple juice in my water bottle.

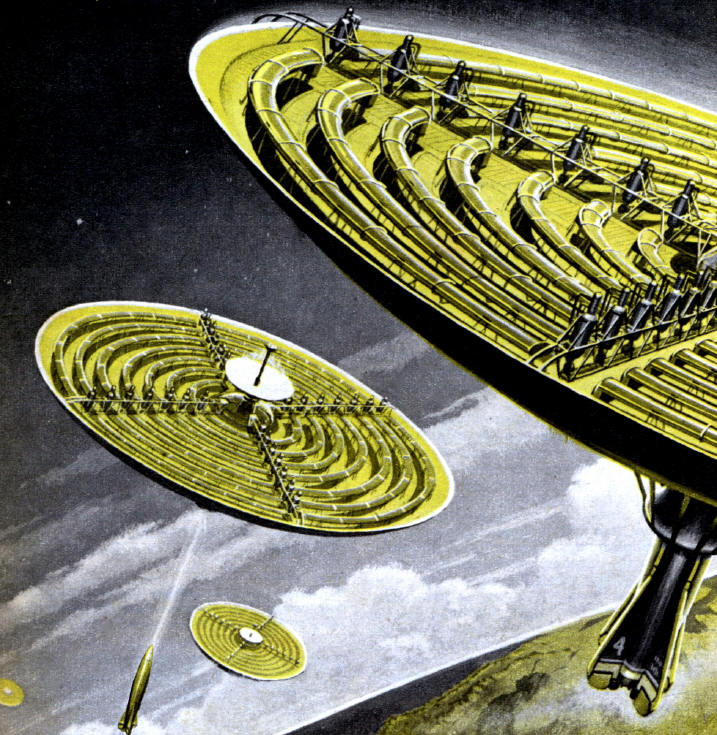

Future Food needs Future Farming. In The Future, farming needs to be done with giant robots.

Here, we are growing corn underground. Which is where you should grow corn.

Because, a regular, traditional farmer in a regular, traditional above-ground cornfield is soooo not The Future.

Are the guard towers to keep the corn from escaping?

In The Future, we grow food in space. Because, you know, vegetables don’t grow on the Earth, on the farm just down the street. Vegetables only grow in space.

It makes perfect sense. When you think about it.

Today’s factory farming and factory food are a total horror. It didn’t happen by accident. It happened, at least in part, because people wanted it that way. It was The Future. You can’t stop progress.

When you think about it, this is utterly bizarre. It’s not like people didn’t have good food in 1910 or 1925. The food then was fine — vastly better than today. But … they were dreaming of food pills and food factories and corn grown by underground robots.

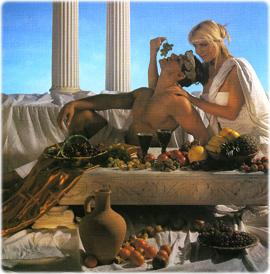

Eating is one of humans’ most basic pleasures. Especially eating well. Like sex, but three times a day. In my future, we eat really, really well. Here’s a different vision of the future.

Jean Georges Vibert. The Marvelous Sauce. 1890.

A marvelous sauce. Isn’t that a more relevant accomplishment than growing corn underground? Tastes better, anyway.

Who needs a conveyor belt.

Food is supposed to be fun.

This is a dinner in Kyrgyzstan. We should be eating at least as well as the Kyrgyz. At least, I think so.

So, who cooks all this food?

Basically, women do. As they have, in every culture, for the last 790,000 years, since the discovery of fire.

Women like to cook! Who do you think is buying Gourmet, Bon Appetit, Food and Wine, watching cooking shows on TV, and all that? What they don’t like is working from 8-6 in the salt mines, going shopping, and then cooking. Ugh. We need more free time. (Of course my fabulous future includes much more free time, especially for women.)

Food circa 1910 is fine by me. Slow food. This is not exactly a novel idea. But, we have to embrace it, and consequently drop The Future — forever. No more pill food. No more factory food. No more genetically modified crapola grown by robots.

Along with Real Food comes some Real Farming. I like to kick around the sustainability types at every opportunity, but this is something they’ve done really well. Between the permaculturists, Natural Farmers (Fukuoka-style), the Michael Pollan local-foodies, and so forth, we have a pretty good idea of the Future of Food.

However, as I’ve said in the past, it is an incomplete picture.

April 19, 2009: Let’s Kick Around The Sustainability Types

Since we’ve gotten a little tired of The Future, and its factory chemical robot food, there has been a corresponding reaction to return to The Past. The Past is a bit of a fantasy, just like The Future. In the U.S., The Past is mostly the Little House on the Prairie Fantasy of the self-sufficient pioneer farm. That did exist, but that wasn’t all.

Was this The Past? (The Gleaners, Jean-Francois Millet, 1857)

Or this? (Holyday, James Jacques Tissot, 1876)

To be honest, I’m about as tired of The Past as I am of The Future. First of all, I’m not at all convinced that The Past is a good agrarian format. Indeed, it is rather a lot like our system today, just minus the machines — the forcible extortion of fertility from the land, via crop monoculture. Fukuoka seems like an old-time farmer at first glance, but it soon becomes apparent that what he was doing was nothing like farming of old. For example, he grew rice in a dry field, without weeding or cultivation. Other farmers thought he was nuts. Even after he started pulling in the highest rice yields in the world, with three days of work per year and no mechanical devices, they still thought he was nuts. Only in the last few years have I seen people start to catch on to this “no cultivation” idea. Also, he mixed seeds to encourage vegetables to grow “like weeds,” which is the complete opposite of the neatly-organized “kitchen garden.”

Another idea I’ve been toying with is the notion of having no domesticated meat animals. This was the situation in Japan until the mid-19th century, when they adopted meat production as a form of “westernization.” Japanese people ate meat, but it was all wild meat — fish, mostly, with some wild boar, deer, fowl and so forth. Nature is fantastically productive of meat when left alone, to an extent that is practically unimaginable today. When the European explorers first visited Chesapeake Bay, they found sturgeon (a freshwater fish) in superabundance, and in sizes up to 18 feet long and weighing 1800 lbs. And cod, of course. Here is a description of herring found in Virginia in 1728:

When they spawn, all streams and waters are completely filled with them, and one might believe, when he sees such terrible amounts of them, that there was as great a supply of herring as there is water. In a word, it is unbelievable, indeed, indescribable, as also incomprehensible, what quantity is found there. One must behold oneself.

You can find similar descriptions of salmon, or of buffalo upon the plains. When you think about it briefly, it makes perfect sense that the greatest abundance of meat is possible from unmolested nature, as the conversion of solar energy into meat is most direct. Scientific studies have confirmed this — that it was a far more efficienct process to have buffalo eat grasses upon the Great Plains, than it is for people to grow corn and then feed it to cows stuffed in warehouses as we do today. And so much less work. And — to the degree that hunting is fun, and fishing for 1800 lb. sturgeon is really fun — so much more fun! Of course, wild meat is much better than the hideously degraded garbage you find in stores today.

Some people around here like to go up to the Saint Lawrence Seaway during salmon season. In a few days, they can get a couple hundred pounds of salmon, which is not too hard at 50lbs each. Or, for the deer hunters, a single deer will produce 100 lbs of meat. Two deer and a few fish per year — about four weekends of playing in the woods with your buddies — is a lot of meat. In the olden days of superabundance, it was a lot easier than that. How much meat is in a buffalo? Maybe we could hunt for our meat ourselves.

Thus, in my fabulous future, vegetables and grains are grown Fukuoka-style, but meats are harvested from the wild. In the past, no European culture has been able to manage their interactions with nature effectively. Overharvesting and destruction of the habitat quickly follows. But this is my fantasy future, and I think this is a much more sensible fantasy than growing tomatoes in orbit.

Thus, as far as food production goes, we end up with something that is nothing like the present, not at all like The Future, but also nothing at all like The Past.

We didn’t get past food: today. We will spend more time investigating the old, worn-out Future, and also our new, much better future, in the future.

* * *

Time for national newspapers: Recent statistics on U.S. newspaper circulation are horrible. These reflect a simple fact: most newspapers stink. USA Today? Gimme a break. But, it’s still better than 80% of what’s out there.

The heyday of newspapers was before 1930. In those days, the newspaper was the only source of news available. The business naturally lent itself to atomization because of the reality of printing a daily publication: you had to be within one day of the printing press, and there was no way to move the formatting and layout from one press to another quickly. In those days, a newspaper was literally made of hot lead, melted down again each day to reform the printing plates.

Thus, we had city papers, each of which had an effective monopoly, or at least didn’t have to compete against papers from other cities. Also, they didn’t compete against radio, TV or the Internet. A weekly or monthly periodical could be a national publication, since it could reach everyone via the mail.

Radio and TV changed things somewhat. You could follow a sports game in real time, rather than having the choice of either buying a ticket at the stadium or reading about it the next day. However, neither radio nor TV could transmit as much information as a newspaper.

Today, we can easily transfer the layout and contents to a printing press anywhere. This enables national newspapers. Newspapers in most countries are national. Japan’s Yomiuri Shimbun has 14 million subscribers, compared to 2.1 million for the Wall Street Journal and 1.0 million for the New York Times. Korea’s Joongang Ilbo has 2.1 million subscribers. Even Thailand’s Thai Rath has more readers than the New York Times, at 1.2 million.

The logical next step for U.S. newspapers, it seems to me, is to aggregate into national papers. In the U.S., I would suggest the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, and maybe one more — not including the already-national Wall Street Journal. These papers are actually readable and interesting, as opposed to the direct-to-birdcage San Francisco Chronicle for example.

The New York Times should start this trend by scuttling the Boston Globe, which it already owns. Existing Boston Globe readers get the New York Times delivered, with a big Metro Boston section added. Keep 20 or so reporters and some advertising salespeople for the Metro Boston section, and the rest take a hike.

Then, the New York Times should do the same with the 15 other regional newspapers it owns.

After a while, people in Boston and elsewhere are going to get irritated by reading a newspaper with “New York” in the title every day. Ugh. At that point, the New York Times would change its name to something less regionally-specific. I’d suggest the Times.

What about all those laid-off reporters? There is still a great demand for information and insight, which people will pay for. However, I think it would be very specific and focused — more like investment newsletters. For example, a former Boston Globe reporter could publish a monthly Boston Commercial Real Estate Report from his home office, and charge $150 a year. If it had real “can’t get it from a newspaper or blog” insight — which is not too difficult for a person focused on the sector full time — it would be worth every penny and more. A “who is doing what to whom” version of local Boston politics called The Action in the Backroom could be a lot of fun. A more adventurous character could do a newsletter called The Real Afghanistan. Mabye the Emerging Diseases and Pandemic Watch would find an audience. Since there are no advertisers to please, and they don’t have to dumb-down the content to the community average, they could be very saucy and interesting.