Finally, we come to the last of what I find are the primary theories of some kind of monetary problem contributing to the Great Depression: the idea that there was some kind of dramatic rise in the value of gold.

As I’ve said before, this is something of a minority theory. It was not part of the Keynesian narrative; not part of the Monetarist narrative; not part of the Austrian narrative; and mostly not part of the Blame France narrative, except in a small way. It was most memorably expressed by Gustav Cassel. However, Cassel mostly formed his ideas before 1930; even, I would say, before 1910. So, even Cassel was something of a broken clock on that issue. He applied his conclusions, reached decades earlier, to the matters at hand.

To summarize some of the arguments presented in earlier pieces:

1) The term “deflation” is unfortunately applied to a variety of very different situations. One is a situation where the value of the currency rises; for example, its value compared to gold or other currencies. Another is a variety of situations which might produce falling nominal prices, but where the value of the currency actually does not change.

2) If a currency value is linked to gold, then the only way to get a rise in the value of a currency is for the value of gold itself to rise.

Now, I should probably stop here and make some remarks about what I mean by “a rise in value.” This is NOT A RISE IN “PURCHASING POWER”. “Purchasing power” is basically the inverse of nominal prices. Rather, it is a change in the market value of the currency, as expressed in the foreign exchange market for example. If a currency was $20.67/oz. of gold at one point, and then $35/oz. gold a little later, then the value of the currency has obviously declined vs. gold.

Unfortunately, we really don’t have a definitive measure of the value of gold. There is nothing that anyone has found, that is a better measure of this “absolute value” than gold itself. We would expect that, if the value of gold declined substantially, that it would naturally take more and more gold to buy other things; “rising prices” in terms of gold. However, the real market values of other things can also rise for their own reasons, even when measured in a standard of value of perfect stability.

Now, let’s postulate that the value of gold rose suddenly, perhaps beginning around 1929 and going into 1933 or so.

First, this is a sudden rise. It is a period of only about four years, perhaps less. That is very different than a rise that might take place over twenty or fifty years.

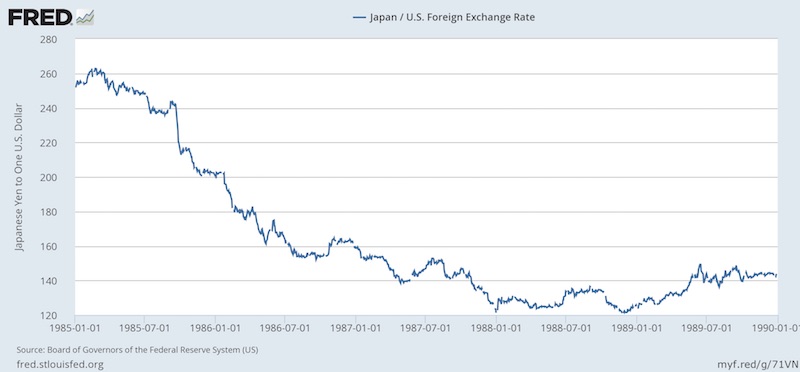

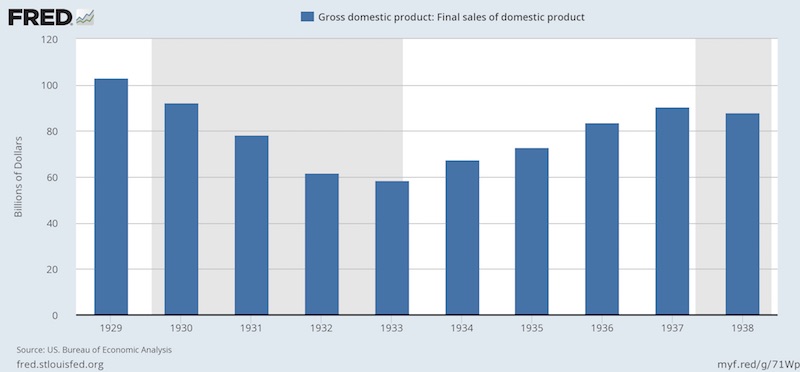

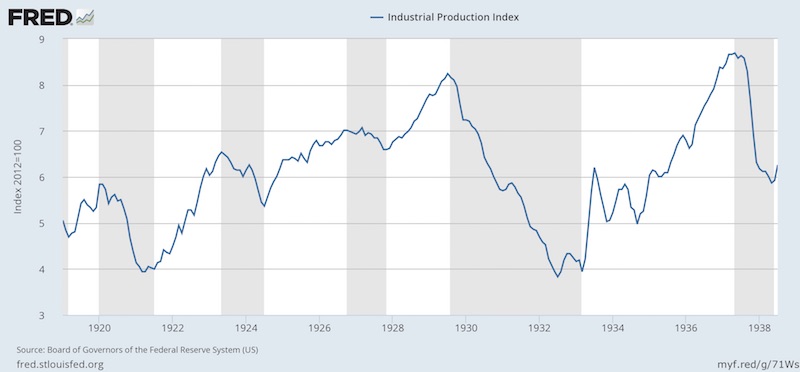

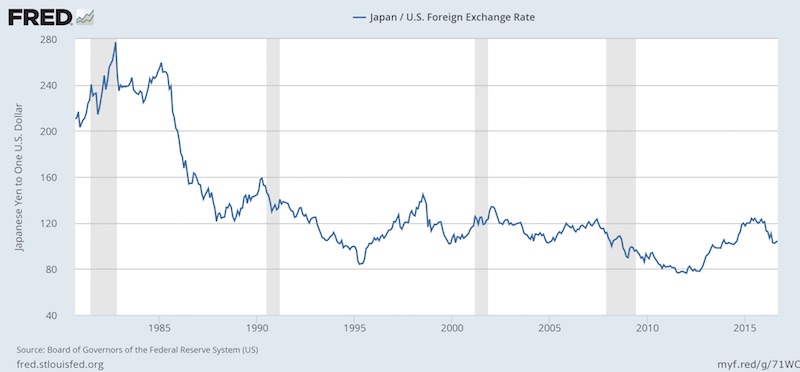

Second, the magnitude of the rise must be very large, to cause, by itself, anything like the effects witnessed during those years. How much of a rise in the value of the dollar today, vs. the euro perhaps, would it take for U.S. nominal GDP to decline by 43%, and Industrial Production by 54%, in the absence of any other factors? I would say that it would take at least a rise of 100% — for example, a rise from $1.20 per euro to $0.60 per euro, assuming no great change in the value of the euro. We actually have seen rises of that magnitude, such as the rise of the Japanese yen from 260/dollar to 120/dollar in 1985-1987. This was less than three years. It was certainly problematic — but it definitely did not cause anything resembling the 1929-1933 period of the Great Depression. So, maybe even a 100% rise would not really do it. Maybe we are talking about a 200% rise here.

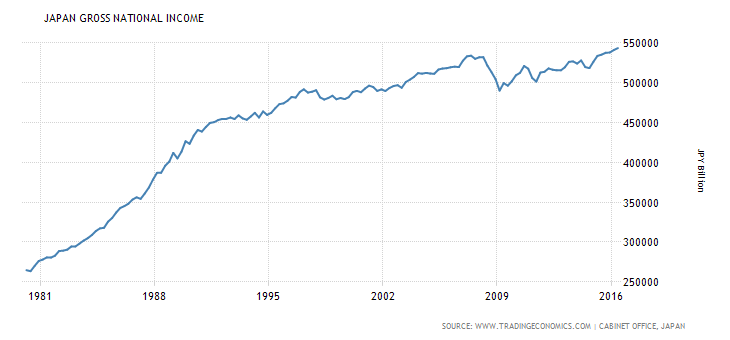

Just to give a comparison for the magnitude of the economic collapse of the 1929-1933 period, here’s nominal Gross National Income (similar to GDP) for Japan for 1985-2015. This is after the 100%+ rise in the yen vs. the dollar after 1985 (the yen later went to 80/dollar), plus a great many other factors including a long period of recession beginning in 1990, demographic issues, and all the rest (tax hikes, among other things) that have contributed to Japan’s 25+ years of poor economic performance.

As we can see, there is nothing comparable to the 40%+ decline in nominal GDP that the U.S. experiened — even with the gigantic rise in the yen’s value. So, if we are going to blame a rise in the value of gold for the downturn of 1929-1933, we are talking about a very big rise indeed, to produce the kinds of effects witnessed.

This is a longer-term look at the yen, showing the rise to 80/dollar and even beyond.

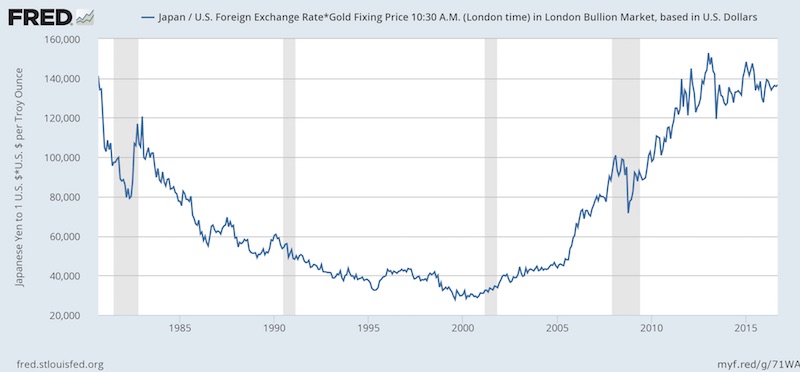

This is a chart of the yen vs. gold, showing a rough tripling of the yen’s value vs. gold between about 1984 and 2000.

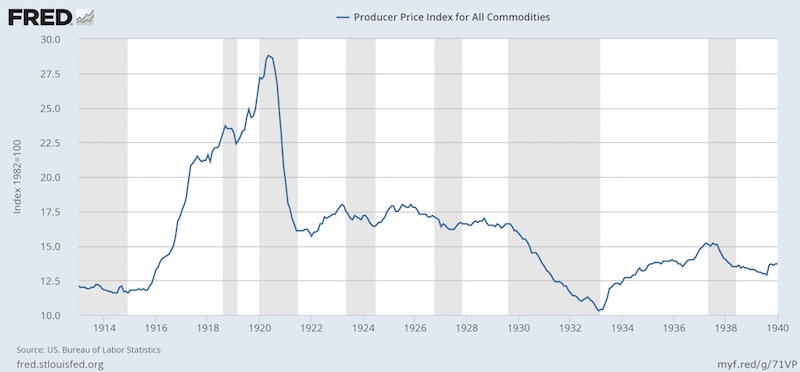

Now, to give an idea of what was going on in terms of prices, here is a Producer Price Index for 1913-1940. It is close to a commodity price index, although a little more broad.

We can see a big rise related to World War I, and then a decline soon after the end of the war. Besides the supply/demand issues of wartime, there was an issue with a weak dollar that was corrected in 1920-1922, which doubtless contributed both to the rise and decline of nominal commodity prices around WWI. We talked about that here:

August 25, 2012: The U.S. Dollar During WWI and the Recession of 1920

Then, we have a nice flat plateau during the 1920s, at a relatively high level — prices were generally much higher than they were in 1913. There’s a decline of roughly 38% beginning in late 1929 (and not before), although this brings prices actually to just a little below where they were in 1913. Beginning in 1933, there is a rise in prices, which is closely related to the devaluation of the dollar from $20.67/oz. to $35/oz. during that year.

When you look at measures of commodity prices such as this, I have to remind you again that you must not make the assumption that the value of gold is the inverse of commodity prices. Our desire to have some definitive measure of gold’s value is so great, that it is all to easy to press one or another thing into that role, for which it is not at all suited. For example, we might postulate that the higher commodity prices of the 1920s reflected a lower real market value of gold, and no real change in commodity value. Or, it might just mean higher prices, as measured in a unit of account (gold) with no real change in value. Or, it might even be a combination of the two.

As David Ricardo explained in 1817:

It has been my endeavor carefully to distinguish between a low value of money and a high value of corn, or any other commodity with which money may be compared. These have been generally considered as meaning the same thing; but it is evident that when corn rises from five to ten shillings a bushel, it may be owing either to a fall in the value of money or to a rise in the value of corn. . . .

The effects resulting from a high price of corn when producedby the rise in the value of corn, and when caused by a fall in the value of money, are totally different.

Here’s Ludwig von Mises on the same topic:

It is a popular fallacy to believe that perfect money should be neutral and endowed with unchanging purchasing power, and that the goal of monetary policy should be to realize this perfect money. It is easy to understand this idea as a reaction against the still more popular postulates of the inflationists. But it is an excessive reaction, it is itself confused and contradictory, and it has worked havoc because it was strengthened by an inveterate error inherent in the thought of many philosophers and economists. . . .

Changes in the purchasing power of money, i.e., in the exchange ratio between money and the vendible goods and commodities, can originate either from the side of money or from the side of the vendible goods and commodities. The change in the data which provokes them can occur either in the demand for and supply of money or in the demand for and supply of the other goods and services.

(Both of these quotes are from Gold: the Once and Future Money.)

Why might commodity prices (real commodity values as represented by a stable measure of value) be higher in the 1920s than in 1913? For one thing, a lot of commodity production was destroyed in WWI. Less supply. Second, there might have been a lot of demand for commodities, both due to postwar rebuilding, and also due to the generally booming economies of “the Roaring Twenties,” especially in the United States.

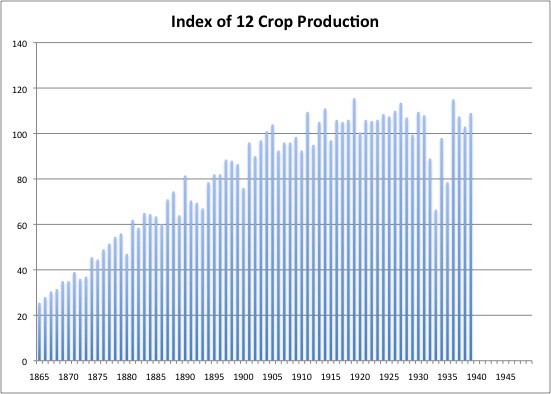

This is a topic that I would like to treat in much more detail sometime. For now, I’ve made only some early investigations. It appears to me that the decline of commodity prices into the 1890s, and the rise into the 1920s, was in both instances closely related to the supply of commodities. There was a vast expansion in commodity supply worldwide in the 1870-1890 period. For the first time ever, railroad expansion and steamships allowed vast swathes of land to be planted for agricultural commodities to be shipped and sold elsewhere. Before the era of rail and steam, most agricultural commodities were consumed within the local area, unless they had close access to rivers or canals. The result of the railroad expansion was a gigantic increase — more than a doubling — of land under cultivation in the U.S. after 1870. Much the same thing was happening in vast areas elsewhere, notably South America including Argentina and Brazil; all of southern Africa; some of Asia; and Canada, Australia and New Zealand. A flood of agricultural commodities hit the world markets, driving down prices.

I looked into it here.

February 26, 2012: The 1890s

This is a chart of production of the twelve largest crops in the U.S. In this time, the yield per acre was basically stable; so the chart of land under cultivation looks much the same.

We can see the gigantic rise in production after 1870, an increase of about three times to 1905. Then, after 1905, production is basically flat until after 1940. From this alone, it should be no surprise that when the growth rate of production was the highest (1870-1890), prices were falling, and flat production after 1910 led to higher prices in the 1920s.

Despite the difficulty of coming to definitive conclusions, I think it is pretty clear that the evidence does not suggest that there was any meaningful rise in gold’s value, between 1913 and 1928. A rise in gold’s value would suggest lower nominal commodity prices, and probably a moribund economy. What we have is higher nominal commodity prices, and a booming economy. The exact opposite.

So, if there was any factor potentially causing a rise in gold’s value, we can see that it was definitely not effective before 1929. (The drop in commodity prices after 1919 can be completely explained by the end of hostilities, and also the monetary adjustments of 1919-1922.) So, if there was something that caused a gigantic rise in gold’s value — a rise of perhaps 100%, 200% or even more — it seems reasonable to expect that it must have appeared around the end of 1929, and was not extant earlier.

I haven’t really even warmed up on this topic, but already I think we will have to resume it next week.