The New World Economics Guide to Curing Affluenza 2: the Affluenza of the Poor

December 15, 2013

Earlier this year, I looked at the thinking process of a friend of mine who basically had “affluenza.” He made decent money — actually, more-than-decent money — but it all disappeared somehow. The funny thing is, he didn’t even have a blingy lifestyle. It all disappeared before he even had a chance to bling it away.

June 16, 2013: The New World Economics Guide to Curing Affluenza

I got to thinking that his basic thought processes are present in American life at all levels, even the working (or non-working) poor. Yes, even at minimum wage, people have the characteristic patterns of “affluenza.”

I say “patterns” because it is a certain characteristic American thought pattern, which really doesn’t have anything to do with income.

Minimum wage is $7.25 per hour, or about $14,500 per year for a full time 40-hour-per-week load (could be multiple jobs). Often, localities have a higher minimum wage than the Federal minimum. It is not a lot. But, it should also be enough. It should be more than enough. We still live in one of the most materially abundant societies the world has ever seen. You can get a lot for $15,000.

Most of the best things in our civilization are actually free, or nearly so. Public libraries, public parks, beaches, museums, the Internet, and so forth provide most of the best our civilization has to offer. Even a genuinely poor person can afford a $75-per-year membership to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which is a really fine museum. I’ve always found it interesting that you never see anyone there who is plainly of a lower income, although they are abundant on the subway you ride to get to the museum. (Indeed, there are some low-income neighborhoods that are an easy walk from the museum.)

Even on minimum wage, you can afford things that even kings didn’t have a few centuries ago. Electric lights. Refrigerators. Hot and cold running water, and modern sewage systems. Indoor flush toilets. Hot showers. Weekly trash removal.

Orange juice. And pepper!

Even a cellphone, if perhaps a prepaid one. They used to call cellphones “carphones,” because they were so big you needed a car to carry it around. That was only 20 years ago.

You can get a decent notebook computer for $450, brand new. If it lasts for a typical four years, that is only $112 per year.

Wow.

Many other material things you can get for free, or nearly so. I often contribute to a church charity nearby called Magic Closet. A few hours per week, you can bring anything you like there, and donate it to charity. You can also take whatever is there, for free. No limit. Flat out free. It is like Goodwill or Salvation Army with no money in between. Just give it away for free and get it for free. I think it’s a great way to interact with your neighbors, and also to clear unused stuff from your house and get it in the hands of someone who can make use of it.

You can get clothing and housewares of all sorts there, certainly enough for the basics of modern living. It is even pretty good quality. I know because I drop off a lot of stuff there myself (it seems to build up continuously), and the stuff I’m dropping off isn’t junk.

You can even get big-ticket items like furniture, for free or nearly so, if you ask around. Pretty much everyone has a thirty-year-old sofa in the garage, which is still in good usable condition. If you ask nicely, they will probably give it to you.

I once gave away a piano. It ended up with some Chinese people from Brooklyn.

You would think it is the best possible time to be poor, particularly since the advent of things like Craigslist or eBay, where you can get things for much cheaper than new, or sometimes for free.

On top of this, we have various government services, like Medicaid, available to the lowest incomes. For free.

Twelve years of public schooling — for free!

So, what’s the problem?

There are a number of problems, but one problem is the same problem we have throughout American society today. Affluenza. It is really not so much a question of needless luxuries, but rather that the “basic American lifestyle” is too expensive.

There are plenty of people in the U.S., making very little money, but who are quite prosperous in their way. Mostly these are immigrants. They haven’t been raised in American society, and don’t have American expectations or American ways of doing things.

They don’t own automobiles, because, where they are from, nobody owns an automobile. They probably don’t even know how to drive. (My wife, whose father owned a Honda dealership, did not drive on a public road until after age 30.) They ride bikes. When they need to travel farther, or carry loads, they share vehicles or hire one from another person much like themselves.

They will often pile into a typical surburban house, with a family (or four working men) in each bedroom. There might be twenty people in a house. On a per-person basis, it is pretty cheap, because they can split the electric or heating bill twenty ways.

Heck, I did that in college. It was actually pretty fun.

They cook for themselves, with simple nutritious food based on rice, beans, basic vegetables and so forth. It costs almost nothing. It takes labor, but one woman can easily cook for many, which is what people do and what they have always done, where they come from, and indeed in all places throughout history. If they are going outside the house, they bring some food with them. (Often, in food service jobs, you can get food for free anyway.)

Now, I am not saying that sharing a bedroom with three other men in a boarding house is as nice as having a 2500sf suburban house of your own. Did I say that? I didn’t say that. But, if you have a low income, it is not a bad solution, and indeed is perhaps not a bad way to live in any case. It depends mostly on the other people. Not everyone is badly behaved. Military people live in more materially austere conditions than this, but they are generally well-behaved, and it goes well enough. Immigrants usually know how to live with each other and behave themselves. Many American poor do not.

Do you remember the TV series M*A*S*H? It was about a team of battle surgeons in the Korean war. They lived in dirt-floor tents, a few miles from the front lines. On cots. Shared. It was OK. After the war was over, they probably remembered it as one of the most interesting times of their lives.

Of course, one of the problems is that people are badly behaved. This is a problem, but it is not really a problem of income. It is a problem that we attempt to solve with income — moving to a neighborhood with better-behaved people, which costs more money.

I am not necessarily saying that one should live in a shared house of some sort. That is just one way that people deal with the basic problem, which is a lack of cheap but pleasant housing options in the United States. It is a symptom of a broader problem in the U.S., which is not a problem in other places in the world. It is not really that difficult to make small apartments and even freestanding houses, of perhaps 250sf-450sf or so, that people could live in. 250sf probably doesn’t sound like much — it’s not — but, it is about the size of the typical travel trailer, 8×30, which many people do in fact live in (about 6% of the U.S. population, which is 18 million people). The advantage of a proper apartment is that it would be better insulated, and have better water and sewage connections. The only real difference between a 2500sf shared house and ten 250sf apartments in a single building is more bathrooms and kitchens, which are not real expensive. (Actually, due to shared hallways, it would be more like eight 250sf apartments.)

In India, the Tata corporation has been building “nano apartments” that sell for $7,800 to $13,400. Maybe they would cost double that in the United States, due to higher labor costs. But still, that would be $15,600 to $26,800. It can be done. These apartments are 218 to 373 square feet. Which is small. But is it too small? This American family of four lives in 165 square feet. And they like it! They aren’t complaining about being poor. In fact, they aren’t poor. They own their own house free and clear, are able to save a lot of their income, and also have been able to be more flexible about their job choices than otherwise. They are living a life of abundance.

This American family has twelve kids. They voluntarily sold their suburban house and are now living — all fourteen of them — in an RV! And loving it. Fourteen people in 240 square feet. Which is pretty incredible. But, it can be done, and it can actually serve as the foundation for a fantastic lifestyle. Of course, it doesn’t have to be an RV. It could be a regular 240 square foot house. For some reason, we think that living in an RV, or a sailboat, with 240 square feet would be romantic and fun, even with thirteen other people, while living in a 240 square foot house would be miserable and intolerable. Which doesn’t make any sense at all. It’s affluenza.

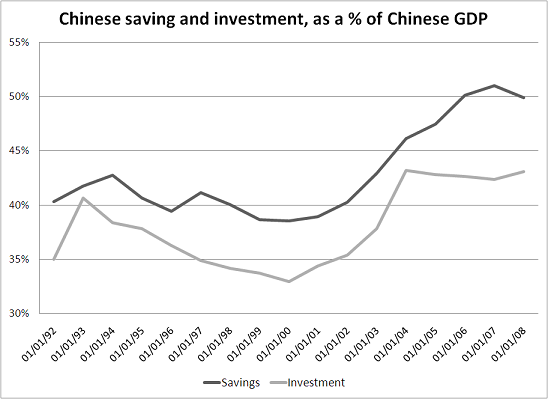

We just don’t do this. Why not? It’s not the “American way.” This is formalized in many places with rules that make it actually impossible to create such apartments. If you are making $15,000 a year, you need housing that costs maybe $200 per month, or can be purchased for $15,000-$25,000, or even built for $12,000 or so, and has minimal utility costs. This is not hard to do. In fact, it is easy to do. And, people in other countries do so. What kind of apartments and houses do you think people live in in China, India or Mexico? How do you think it is that a Chinese working-class family has a 50% savings rate — on average! Why don’t we do this? We just don’t. It is a form of “affluenza.” We want more than that. We don’t need more than that, but we just want more than that.

I told my upper-middle-class friend that he should live in a two-bedroom condo, in a nice neighborhood, near a subway station. He could sell his big single-family-detached house with a yard, and live in a condo instead. In the process, he could buy the condo with cash, pay off all his debt (plenty!), and live comfortably and happily — indeed, luxuriously, more luxuriously than he lives now — with a savings rate of 30%+, instead of 0% or less (he gradually accumulates debt over time). Plus, he would have a lot fewer junk obligations, like yardwork and house maintenance, and be able to commute by subway, thus eliminating the need for a second car and a teeth-gnashing commute twice a day. Why doesn’t he do this? The advantages are immense. There are no real hardships — actually, he would be better off, with more free time and an easier commute, not to mention the peace of mind that comes from a 30%+ savings rate. He just doesn’t. Or won’t, even when I spell it out to him in detail. It’s affluenza.

The biggie of course, for lower incomes, is the car. They basically can’t afford a car, but they try. The consequences are easy enough to predict. First, you get a job that requires a car to get to — because you have a car. Pretty soon, that “unplanned” $350 repair bill comes, and you need the car to get to work, so you make a trip to the payday lender. The first of many.

You could live, even in the midst of the most horrible automobile-dependent Suburban Hell (Phoenix, Arizona for example), without a car. Most low-income jobs are not real geographically specific. These are jobs at McDonald’s and WalMart, pretty close to anybody. With a bicycle, you could easily get to anywhere in a five-mile radius or so (about 25 minutes on a bike). But, we don’t want to live that way. We want all the freedom and options that a car introduces, particularly in our auto-dependent environment. It’s affluenza. We don’t need it. We just want it.

Our American affluenza is not only on the individual level, it is on the collective level as well. Our insistence on reproducing Suburban Hell, over and over, of course introduces automobile dependency. This is why lower-income people feel they “need” a car — because they live in a Suburban Hell wasteland of car-dependency. We could set things up so that people don’t need cars. They might have cars if they can afford them, but they don’t need them. For example, you can live pretty much anywhere within the range of the New York subway system without a car. Now, I think that the 19th Century Hypertrophic format, as represented by Queens and the Bronx, is indeed an ugly and difficult environment to live in. That’s why I suggest the Traditional City format instead. Also, there area lot of badly behaved people in New York City. It’s why so many other people would rather live in the suburbs, despite all the problems including high cost, long commutes, car dependency, and all the other Suburban Hell miseries. The point is, we could set things up so we don’t have car dependency, but we don’t. We think we need our single-family freestanding farmhouses with our own yard, and our automobiles, and find a way to force this upon ourselves. It’s a collective affluenza.

If lower-income people just stopped wanting to reproduce the “American Way,” and instead turned their attention toward the kinds of things I am talking about, it would appear before them. When 50% of the U.S. population wants to live without the cost and difficulty of an automobile, then these options would become immediately and more easily available. When they want to live in a modest 300-400sf arrangement of some sort, instead of a 2500sf suburban house, then these arrangements would appear. Instead, they are participating in our collective “affluenza,” doing everything they can to reproduce the grotesquely expensive Suburban Hell/automobile dependency pattern, even if, financially, they can’t.

People think that “affluenza” is an aberration — doing something that is different than what others in what you perceive to be your peer group are doing. That’s not the problem at all. In America today, “affluenza” is doing the same thing as others in your perceived peer group are doing. To cure yourself of affluenza, you have to do something different than what others do. It can’t just be a little thing either, because that won’t move the needle. You have to make big changes. For example, would you be willing to live, with your family of four, in a one-bedroom apartment or condo? Just one bedroom. “Absolutely not! Every child needs their own bedroom, especially if they are of different genders. And of course, the parents need their own bedroom too, for obvious reasons.” Is it so obvious? Native Americans could easily build new shelters. It only took them a few days to make a new hut of some sort. They could have had a separate little hut for all of their children if they wanted to. And yet, they would live, parents and children together, in one single structure. This was also true of preindustrial people elsewhere in the world, even when they really didn’t have to do it that way if they didn’t want to.

Maybe it is the natural human way to live?

We look with admiration, and even longing, at a family of fourteen that lives in a (one-room) RV, but the idea of having parents and children sleep in the same room in some kind of enclosure without wheels or sails makes people’s heads explode. It is just not what people do. Exactly.

The home ownership rate in Mexico is 80%. Plus, only 13% of people who own their houses have mortgages. Think about that. Even the lowest-income people in the U.S. make more than the typical Mexican. But, Mexicans own their houses, with no mortgage. Part of this is because it is common in Mexico to build your own house. It is not so hard, if you don’t have big ambitions. It is hard to build a 2500 suburban house, but it is not too hard to build a 400sf house from cinder blocks, as is common in Mexico. Also, it is relatively easy to do so, in the sense that these options are readily available in Mexico, and everybody does it. It is not blocked by various societal norms, ossified into municipal regulations, that keep people in the cycle of affluenza — owning and spending more than they should, no matter how much they make.

At every income level except the very highest, people have expectations that push their financial capacity to the limit. If you are making $22,000 a year, you think you “should” own a car and live in a freestanding house. If you are making $220,000 a year, you think you should have two cars, and live in a larger freestanding house in a better neighborhood. If you are making $650,000 per year, you think you should have a McMansion in the best neighborhood, drive German luxury cars, have kids in private school, and take two week luxury vacations in Italy with the family. If you are making $15 million a year, like the actor Nicholas Cage at the height of his career, or an NFL star, you think you should have a half-dozen true mansions, at $5 million each, scattered all over the world. In every case, people push themselves to the financial limit. It’s affluenza. And thus, Nicholas Cage goes bankrupt on mortgage debt he can’t pay, while 70% of Mexicans own their own homes free and clear with no mortgage, and Chinese factory workers have a 50% savings rate.

Think of that. It is a kind of mental poison that saturates all of American society today.