Once people get into their heads that maybe the personal automobile is not really such a good idea — in other words, after they have moved beyond the biodiesel/electric car phase, as if the only problem with the personal automobile is the fuel it uses — they usually fixate on bicycles.

I say “fixate” because this often becomes an eco-fetish like so many other such things, as if more bicycles were better, and if you could just get enough bicycles in one place, you could “save the world.”

The focus on bicycles is typically because, in the mind of this person, they still assume that they would be living in Suburban Hell, or perhaps some earlier variant of Suburban Hell (the 19th Century Hypertrophic Small Town America). Of course, if you are stuck in Suburban Hell, with its endless expanses of NoPlace and absurdly long distances between Places, then you would want a bicycle at the very least.

March 7, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to Suburban Hell

July 26, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 3: How the Suburbs Came to Be

July 19, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 2: Downtown

July 12, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village

However, in a a properly designed Traditional City, most people don’t need bicycles. This is true even today. In cities where people often do not own a car, such as New York or Hong Kong or Paris, these non-car-owning people usually do not own a bicycle either. Or, if they happen to own a bike, they do not use it every day as a transportation device. They get by just fine on foot, and using the transportation options available, especially trains and, if a train is not available, a bus. Occasionally a taxi. A bike is best as a least-desirable option, for those trips that are too long to walk comfortably, and not convenient by either train or bus. Ideally, these would be as few as possible, as a well-designed city should be a place where you can easily walk or ride a train (a bus if you have to) just about everywhere.

December 27, 2009: What a Real Train System Looks Like

Bicycles were developed an popularized in the late 19th century. They predate automobiles by only a few decades. Humans have been living in Traditional Cities for 5000 years, and possibly as many as 10,000 years. So, the no-car Traditional City is also, traditionally, a no-bike city. You can have Life Without Cars and also Life Without Bikes.

December 13, 2009: Life Without Cars: 2009 Edition

It should be obvious that it is better to not need a bike than to need one. If you can, you want to design things so that bikes aren’t necessary or desirable. However, many bike fetishists become rather red-faced at this point, as, in their mind, more bikes are better, and anything that is contrary to their visions of As Many Bikes As Possible is to be crushed out by any available means.

This fascination with bikes is really another variant of the My Personal Transportation Device fixation which has been a part of American culture and self-image since about as early as you can go. Before the automobile, before the bicycle, there was of course the horse. I already mentioned the extraordinary proliferation of carriage houses in our typical 19th century American Village, which is completely contrary to any of the European or Asian examples of the walkable Traditional City Village.

March 3, 2009: Let’s Visit Some More Villages

So, we should not think about bikes-instead-of-cars, but rather getting over this unhealthy fixation on My Personal Transportation Device, which is of course unnecessary in the Traditional City. I lived in Tokyo for five years without a car, bike, motorcycle, scooter, Segway or skateboard. During this time I went mountaineering regularly, skied many weekends in winter, went backpacking in summer, and generally traveled over the countryside. Rental cars were available for very reasonable prices if, for some reason, you wanted one. I lived about a five minute walk from a car rental agency. I never rented one. Never needed to.

As we think of Life Without Cars, we should also think of Life Without Bikes. Life Without Cars and Bikes.

For some reason, at this point people then assume that Tokyo is a bad place for bikes. It is not. It is very bike-friendly, and millions of people ride bikes (often from their house to the train station). However, you are still better off without a bike if you can swing it. If you need a bike to get to the train station, maybe you live too far from the train station eh?

I have been promoting the idea of the Traditional City, a place for people instead of cars. What I am worried about is that, if people focus on bikes too much, they will end up with a city optimized for bikes, in something like the way that Suburban Hell is a city optimized for cars. This could be a place with Really Wide Streets, to accomodate all the bike traffic of course. And, it goes without saying, lots and lots of parking space for bikes. (Basically, it would be the 19th Century Hypertrophic City with bike parking lots.) You can see where this might go, and the end result might once again be rather unpleasant for a pedestrian, i.e. a human. I say instead that we should make a city optimized for people, which is the Traditional City, and then maybe sprinkle a few bikes or cars in there to solve specific problems that a few people have, while most people can live happily without either bikes or cars.

February 21, 2010: Toledo, Spain or Toledo, Ohio?

January 31, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York 2: The Bad and the Ugly

January 24, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York City

Let’s now look at some of the specific problems of bikes in a Traditional City environment:

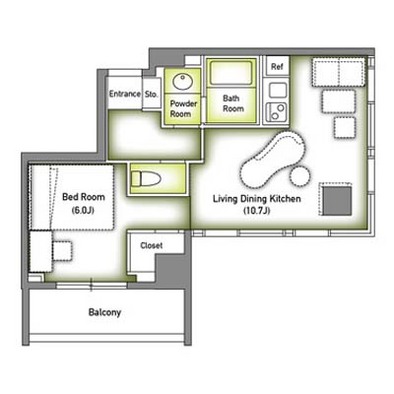

1) Nowhere to put it. Let’s say you live on a third-floor walkup apartment with 350 square feet — a very common Traditional City type arrangement. Are you going to drag your bike up and down the stairs a couple times a day? Where are you going to put your bike in your apartment?

2) Doesn’t go with nice clothes. People tend to wear much nicer clothes in the Traditional City. This is in part because you are always in a Place — where there are other people — instead of a Non-Place. You don’t wear a ballroom gown to a scrap-metal yard, as I say, even if you like ballroom gowns. The endless Non-Place of Suburban Hell is like a scrap metal yard. People tend towards jeans and t-shirts. The Traditional City is more like a ballroom. It is the appropriate place for nice clothes, so that’s what people wear. This doesn’t really go well with bikes, though. Just try it. Put on a nice suit, or a dress, and go ride your bike for three miles. In all sorts of weather. Let me know how it went.

October 10, 2009: Place and Non-Place

“That stripe on my back is where I rode my bike though the puddle.”

Vienna, 1780s.

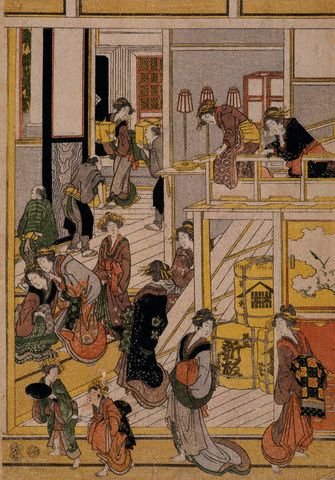

“That is an absolutely stunning kimono!”

“Thanks! It’s easy to bike in too!”

Edo (Tokyo), circa 1810

“Let’s just bike over to my apartment and have a drink.”

3) Doesn’t go well with other kinds of transportation. The Traditional City is a walking-based construct. You might have to take a train or a bus from one walking-based neighborhood to another. I sometimes say that you get around a Traditional City with “train-assisted walking.” This works seamlessly: you can walk along your Traditional City neighborhood to the train station, and then step out of the train station right into another Traditional City neighborhood, or even get on a plane or a boat if that’s what you want. What if you rode the train, and stepped off into an environment where you couldn’t walk easily, but needed a bike?

Of course, bikes don’t go with trains and buses at all. I suppose some bike-nutz will attempt to quibble on this point. I have carried my mountain bike on a crowded commuter train once — the BART to Berkley, where I met a friend for a weekend of mountain biking in the foothills of the Sierras — and I wouldn’t want to do it again.

4) There’s nowhere to park it. To most Americans today, the idea that there could be nowhere to park a bike probably seems insane. This is because they live in Suburban Hell, which is about 80%-90% NoPlace, most of which can be used as a bike parking lot. However, the Traditional City is ideally all Place, and no NoPlace. It causes problems when you dump your machinery in someone’s Place. If you put too many bikes in a Place, people don’t want to go there anymore. It becomes a NoPlace — a bike parking lot.

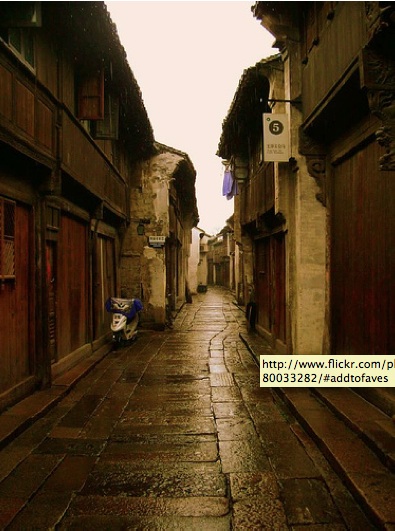

Residential street in a Chinese village. There’s one scooter. Now imagine if everyone who lived here wanted to park a bike on the street. There would be about a hundred bikes in the street. It would look like hell and be rather difficult to walk around in.

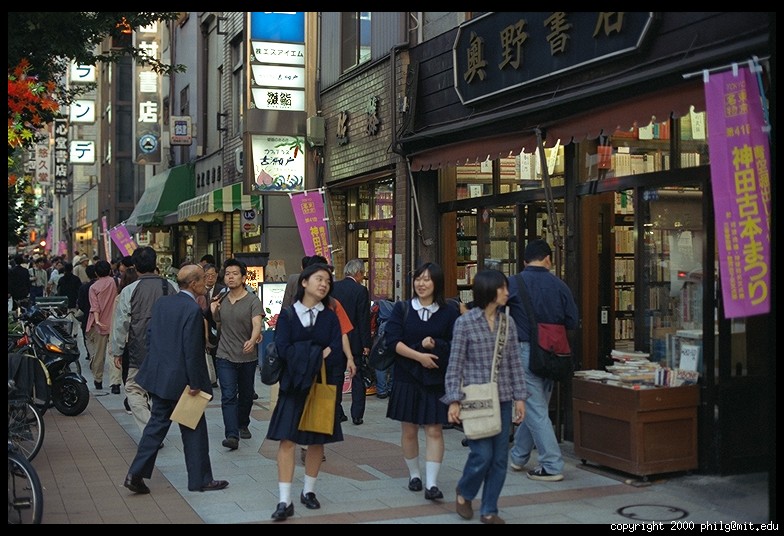

A Traditional City has lots and lots of people in it. Maybe millions. Here is a nice commercial street in Osaka, which is also being used to park bikes. The bikes definitely mess up the Really Narrow Street atmosphere — a place for people, not bikes. I suppose the bike people would say: “what’s wrong with that? So there are a few bikes parked there.” Here’s what’s wrong with it: Osaka is mostly a walking-based city. Maybe only 5% of the people who came to this neighborhood came on a bike. Now imagine what it would look like if everyone came on a bike. There wouldn’t be hundreds of bikes, but thousands. The bikes you see here are not characteristic of a biking-based city. This is typical of a walking-based city (the Traditional City) with a few bikes added. Even so, there are already too many bikes.

Gakugei Daigaku station in Meguro-ku, Tokyo. We used this station earlier as an example of showing how trains and Traditional City walking environments should mesh together. You should be able to step right off the train into a nice pedestrian environment.

Here is the view stepping out of the station onto the street. As you can see, there are a few bikes parked here — blocking the way to the station and also to the storefronts along the street. Store owners get rather irate when you block their storefront with your bike. (Yes, I’ve tested this.) There are about fifteen bikes parked in this photo, being a nuisance to the thousands of people walking along the street and getting on and off the train.

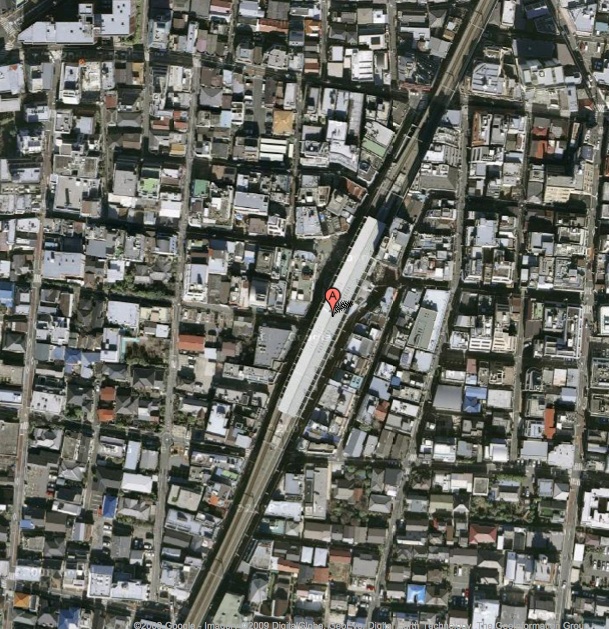

This is the same train station (the “A” mark), with a smaller scale. The area of this square is about one square mile. You could walk from the train station to anywhere in this square in about twelve minutes. The population density of Meguro-ku is about 177 people/hectare. In other words, about 45,000 people live in this photo.

These 45,000 people walk to Gakugei Daigaku train station, to go to work, to school, for shopping, and so forth. Actually there are more, from places outside this photo. The total number of people who make Gakugei Daigaku station their “home station” might be 60,000, or more. Think of those 45,000+ people all using this one train station on a daily basis. Do you see why I recommend heavy rail — full-size ten-car passenger trains running twenty per hour, carrying more than a thousand passengers per train if need be — rather than some little ding-ding trolley? That’s what you need for those 45,000 people to get to where they want to go. Plus, it is way more convenient to have twenty trains an hour than three or four. (It is also far more efficient, as a single train driver can carry 1000 people, as opposed to a ding-ding trolley where the driver carries perhaps thirty people.)

Now imagine if all 45,000 of those people rode their bike to the train station. What would it look like? There wouldn’t be 15 bikes parked in front of the station, there would be fifteen thousand, or more.

You would need bike parking for fifteen thousand bikes. Maybe thirty thousand bikes. In other words, you would do exactly what you should not do: surround the train station with lots of free parking. A NoPlace. No no no!

From this, you can also see that it is perfectly possible to make a city of 45,000 where you can literally walk from one side of the city to the other in 25 minutes. If you are willing to live 25 minutes from the center (or 50 minutes of walking side-to-side), you could make a city of 200,000. That is actually a pretty large city.

5) Walking and bike riding don’t go together. What I call Really Narrow Streets are streets that are sized for pedestrians. This should be the basic format for a Traditional City. Yes, there can be some larger “arterial” streets, but 80%-90% of the streets should be Really Narrow.

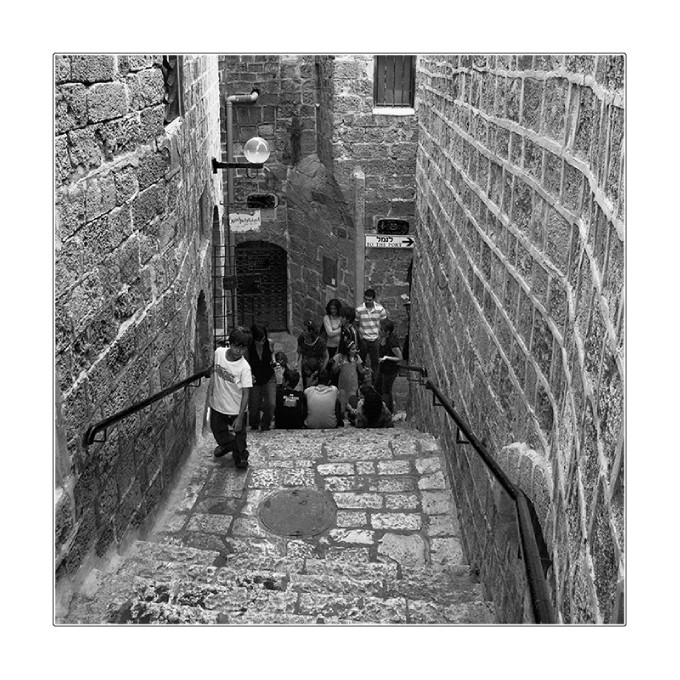

See what I mean? Not really a good place for biking.

However, these are wonderful places for walking, and also for living. They are Places, not NoPlaces.

Of course you want some mysterious back streets like this, where you can sit on the steps with your friends.

Berlin.

The booksellers’ district, Tokyo.

Bars and clubs. Looks a little stark during the day.

You will notice some bikes in these photos. Like I said, it is OK if there are a few bikes. But, this is not a place that is optimized for bikes. It is optimized for people. Which is the way it should be, right?

Imagine if you will a place that is optimized for bikes. There might be four dedicated lanes of bike traffic in the middle of the street. This would be a good way to ride a bike from one place to another at a reasonably high speed, with the fewest hindrances. A freeway for bikes.

Sort of like this (Hanoi).

This is fine for bikes. However, the street then becomes a place that is hostile to pedestrians, i.e. people, just like a street full of cars. It is not a place where you can amble aimlessly down the middle of the street.

Any big city is going to have some “arterial” streets like this. However, as I said, the majority of the streets should be Really Narrow pedestrian streets, and the majority of people shouldn’t own bikes.

Integrating Bicycles into the Traditional City: The last thing we need is a city optimized for bicycles — where people can’t walk from one place to another, but need to ride a bike. Do you want to swap your car dependency for bike dependency? Aren’t you ready to rise up off your wheelchairs and walk on your own two feet?

The best format is that of a Traditional City with Really Narrow Streets, in other words a city designed for pedestrians i.e. people, connected with trains. For smaller cities, under 100,000 people, you probably don’t need anything at all, as you can walk from one end to the other. Bikes can be a solution for those 5%-10% of the population or so who find that walking, trains and buses don’t quite get them where they need to go in a convenient manner. However, if more than 10% or so of the people are biking, it probably means that your walking/train system is messed up or insufficient.

Some people seem to think that trains are somehow not fitting with some sort of “small scale” technological vision they have. Trains are big and complicated. I think this is really just a rationale for My Personal Transportation Device. If you actually added up 45,000 personal bicycles, and compared it with one passenger train, it would probably be about the same in terms of resources and complexity. Technology-wise, trains and bicycles date from the same era, the latter 19th century. There is nothing particularly simple about a bicycle. It is not something you can make yourself on your self-sufficient Little House on the Prairie micro-farm. Go get yourself a forge and see if you can make a ball bearing, or a brake caliper. Not so easy is it. That is why these things didn’t exist in the 18th century.

If, for some reason, you decided that you didn’t want large mechanical devices like trains and buses, then you could design a Traditional City where the only alternative to walking is bicycles. I think Hanoi comes fairly close to this ideal. In that case, you would have some large “arterial” streets for biking from one end of town to the other, and lots of Really Narrow Streets where you get off your bike and walk.

However, in the end I think this just makes things more complicated, as we add in all the problems of My Personal Transportation Device. It is really not that hard to build and maintain a train system. People did it in the 1860s.

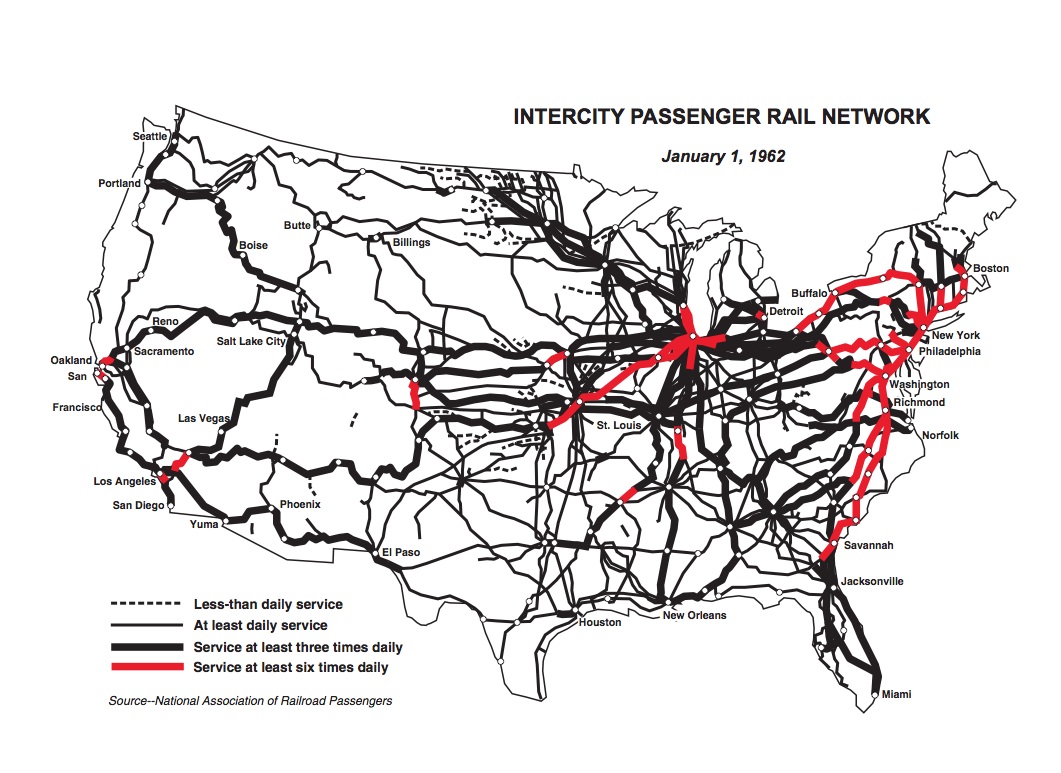

I’ll leave you with this last image, a map of the U.S. intercity passenger rail system circa 1962.

Not too shabby is it? This network has about 88,000 miles of track. China plans to build 70,000 miles of track in the next ten years. That’s how easy it is.

Trains are 10x more energy efficient than automobiles: The East Japan Railway Company provides the primary rail service for the eastern half of Japan, including Tokyo. It serves a population of about 70 million people, and includes metropolitan areas, small cities, and rural lines. It includes high-speed and normal-speed trains, rush-hour and off-peak, commuter and intercity. It is a good measure of a real-life train system under real-life conditions. For 2004, JR East said that it averaged 0.35MJ/passenger-km. A liter of gasoline contains about 35MJ of energy. In other words, the average passenger is getting the equivalent of about 100km/liter or 223 miles per gallon while riding the train. Assuming an average 20mpg for a passenger car and average 1.1 passengers, the train is about 10x more energy efficient than an automobile.

Wikipedia on transportation energy efficiency

What is not evident in this comparison, however, is that in a Traditional City with trains, you make a lot more trips on foot — to school, to the store, to work. Everything is much closer — in walking distance, which is sort of the point. We saw above that you could have a city of as many as 200,000 where you could literally walk everywhere, and not need a bike, train, or automobile at all. Second, the distances are much smaller. You don’t commute 15 or 20 miles, you commute maybe five miles, which seems like a long way because there is so much there there, to paraphrase Gertrude Stein. If your city is all Place and no NoPlace, there is a tremendous amount of stuff in five miles of travel. For example, Manhattan from the southern tip of the island to the northern edge of Central Park is about seven miles. Just think of all the stuff in that distance. So, I would also say that intracity trips would tend to be shorter than is the case for driving around Suburban Hell. If you make fewer trips (because many are walking), and the trips are shorter (Traditional City vs. Suburban Hell), and the train is 10x more efficient per passenger-km, then the true energy efficiency of the Traditional City/train combo is probably 20x-30x better than Suburban Hell/personal autos.

Other comments in this series:

June 6, 2010: Transitioning to the Traditional City 2: Pooh-poohing the Naysayers

May 23, 2010: Transitioning to the Traditional City

May 16, 2010: The Service Economy

April 18, 2010: How to Live the Good Life in the Traditional City

April 4, 2010: The Problem With Little Teeny Farms 2: How Many Acres Can Sustain a Family?

March 28, 2010: The Problem With Little Teeny Farms

March 14, 2010: The Traditional City: Bringing It All Together

March 7, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to Suburban Hell

February 21, 2010: Toledo, Spain or Toledo, Ohio?

January 31, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York 2: The Bad and the Ugly

January 24, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York City

January 10, 2010: We Could All Be Wizards

December 27, 2009: What a Real Train System Looks Like

December 13, 2009: Life Without Cars: 2009 Edition

November 22, 2009: What Comes After Heroic Materialism?

November 15, 2009: Let’s Kick Around Carfree.com

November 8, 2009: The Future Stinks

October 18, 2009: Let’s Take Another Trip to Venice

October 10, 2009: Place and Non-Place

September 28, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to Barcelona

September 20, 2009: The Problem of Scarcity 2: It’s All In Your Head

September 13, 2009: The Problem of Scarcity

July 26, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 3: How the Suburbs Came to Be

July 19, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 2: Downtown

July 12, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village

May 3, 2009: A Bazillion Windmills

April 19, 2009: Let’s Kick Around the “Sustainability” Types

March 3, 2009: Let’s Visit Some More Villages

February 15, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the French Village

February 1, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the English Village

January 25, 2009: How to Buy Gold on the Comex (scroll down)

January 4, 2009: Currency Management for Little Countries (scroll down)

December 28, 2008: Currencies are Causes, not Effects (scroll down)

December 21, 2008: Life Without Cars

August 10, 2008: Visions of Future Cities

July 20, 2008: The Traditional City vs. the “Radiant City”

December 2, 2007: Let’s Take a Trip to Tokyo

October 7, 2007: Let’s Take a Trip to Venice

June 17, 2007: Recipe for Florence

July 9, 2007: No Growth Economics

March 26, 2006: The Eco-Metropolis