The Service Economy 2: It’s Already Here

A while ago, I introduced the idea of the “service economy.”

May 16, 2010: The Service Economy

Economics is the study of how people make a living. How they produce food, shelter, clothing, and so forth. In a modern industrial economy, we do so with a system of specialization and trade. In other words, people are producing goods and services for each other. They are making things for others (goods) or doing things for others (services).

Our national GDP statistics make no distinction between goods and services. Ten gallons of gasoline, at roughly $30, counts just the same as an hour of surfing lessons. A week at Club Med, for $1200 let’s say, counts just the same as a hundred sheets of plywood. Nevertheless, we imagine, for some reason, that producing goods is the only “real” economic activity, and that services don’t count. I said this was a little like when industry first began to appear. People thought that agriculture was the only “real” economic activity, and that manufacturing didn’t count. All the wealthy people were agriculturalists — the landowning aristocracy. They probably imagined the “economy” as being like a giant farm. After a few industrialists became more wealthy than the landowners, people’s views changed such that factories making widgets were the focus of attention. I would even say that this is a major component of the Heroic Materialist style in all things — that more is better, and more means more stuff.

Today, most people see an “economy” as a sort of giant factory. They assume that “growth” means the same thing as today, just more of it. So, if the “economy” is generating 370,000 tons of steel and burning 4 million barrels a day of oil, they assume that, after a period of “economc growth,” it will generate 450,000 tons of steel and burn 5 million barrels of oil. The “Peak Oil” types also assume that, if only 3 million barrels of oil per day were available, then the “economy” would also contract in perfect proportion. It’s like there’s a slider with More of the Same on the right and Less of the Same on the left.

In fact, just the terminology “gross national product” implies this sort of factory-centrism. The GDP statistics date from the late 1940s and early 1950s, after development in the 1920s and 1930s. This was an era of factory-centrism. We “produce” goods but we generally “perform” services. Maybe we should call it “gross national performance”?

This notion is also distressing to the environmentalist types. On the one hand, it seems like if there isn’t “growth,” then there’s horrible unemployment and everyone suffers. However, if there is “growth,” then we end up burning more oil, cutting down more trees, mining more coal, etc. etc. once again in proportion as we push the slider towards More of the Same.

Both of these groups also imagine that their slider, from Less of the Same to More of the Same, corresponds to historical circumstance. So, if they decide that they would prefer Less of the Same instead of More of the Same, they push the slider to the left, which, in their minds means getting in the Way Back Machine and going to some 1880s or 1830s lifestyle.

One reason I bring this up is because I think that the unintended consequences of More of the Same, having built up over decades, have finally reached a point where many people can no longer call “growth” a good thing. Do we need more McMansions and big box stores, with more SUVs to drive around in and parking lots to park in while we burn more oil and kill off more of the natural world, not to mention our own cultural heritage as we gradually decay into a nation of “consumers”? This is why I go on and on about the end of the era of Heroic Materialism. We are so done with that Heroic Materialist crap.

November 22, 2009: What Comes After Heroic Materialism?

I think this has a lot to do with the general unpopularity of “pro-growth” economic approaches (low taxes, stable money) throughout the developed world. It’s popular in the emerging world, in places like China or Eastern Europe. They want what we have. But we’ve gotten a bit tired of this treadmill. However, the alternative, which is economic stagnation — The Same Old Same Old, with more unemployment — doesn’t work so well either. So, we need “growth” that actually represents an improvement in the overall quality of our civilization — our “lifestyle” — which includes things like the natural world.

Previously, I brought up the idea of an economy that is centered on performing arts. Performing arts count as “economic activity” just the same as paving parking lots. This was an intentionally whimsical idea to get people to think about what a “service economy” is. A “service economy” is about people doing things for other people, instead of making things for other people. You could imagine an economy which had an enormous output of performing arts. We would spend a lot of our income on watching live performances, several times a week. Consequently, we would have lots of people employed as performers, and in related jobs. We can see that this has practically no resource component. An economy whose output is performing arts doesn’t require natural resources, doesn’t consume much energy, and doesn’t pollute. You could have “growth” in the form of — not more — but better performing arts. (Most manufacturing is about more but most services are about better. You can’t eat two dinners at once, but you can go to a better restaurant.) In that case, growth would be Better of the Same, which would of course be more highly valued (think of an expensive restaurant compared to a cheap one), and which would then turn up in the standard economic statistics as “GDP growth.” And if you decided that maybe you had maxed out on performing arts, you could enjoy some other sort of service — let’s say massage therapy — or maybe just take the time off. Then, you would have Better and Different. Even taking time off — enjoying more leisure instead of more services — counts as increasing productivity, if not necessarily “growth.” We would have the Same or Better with less work (the Europeans have already been experimenting with this for decades). If we spent 50% of our income on performing arts, or massage therapy, then 50% of the economy would consist of performing arts and massage therapy. To finance our love of performing arts, we would naturally have less of everything else, or in other words, all the people employed in performing arts wouldn’t be producing some other sort of good or service, like building McMansions in the suburbs. Imagine, if you like, a society where people lived in modest little apartments, and didn’t own cars, and didn’t own many other material items either, and didn’t do things that required a lot of resources (like flying to Jamaica for four days in February), but instead walked to the theater several times a week to catch the latest show.

Even in goods production, you can have much the same result. For example, a $10,000 painting counts just the same in GDP as forty $250 air conditioners, which may contain a total of 400 lbs of copper scraped out of a mountainside in Zambia. However, the painting has almost no material component at all. The value comes from the human component. If our values, regarding goods, went from “more and cheaper” to “less and better,” then the material aspect of even manufactured goods could decline rapidly even as their value went up. This “more and cheaper” idea is so ingrained as a part of the Heroic Materialist factory mass-production aesthetic that people often don’t notice that “less and better” is actually quite common. Go ask your wealthy friend: would they rather have a $1,500 handbag from Louis Vuitton or a hundred $15 handbags from Target? If you go to Europe or the wealthier parts of Asia (Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, etc.), you find that people generally have a lot less stuff than Americans, including their much smaller apartment, but it is of much higher quality. Over time, as we have Better of the Same — in other words, economic growth — we might have a $3000 custom-made handbag, which is better than that crappy old Louis Vuitton, and a $20,000 painting, which is much preferable to the $10,000 one. The economists would duly agree that per-capita GDP had doubled. (You might complain that average people can’t afford a $1,500 handbag, but of course that is nonsense. Every high school girl in Japan has a Louis Vuitton handbag handed down from their mother or older sister. Louis Vuitton is for kids; Hermes or Gucci or a custom job is for adults. If every woman buys two $1,000+ bags in a lifetime, and they keep them and eventually pass them along, everyone eventually ends up with a lot of fancy handbags.)

The point is, an “economy” is a pretty flexible idea. It could literally be anything. And, if it is improving — whatever that means to you — then that counts as “growth,” or at least, progress.

May 5, 2008: What Is the U.S. Economy?

The funny thing is, the U.S. economy is already well along this path. Most of the U.S. economy consists of services. Health care. Education. Legal services. Hotels, hospitality, travel and vacation-related. Golf courses. Movie theaters. Restaurants. The fact is, even we — the insanely consumptive goods-obsessed Americans — reach our limits. We’d rather blow $100 at a restaurant than go to the mall and buy more stuff we don’t need.

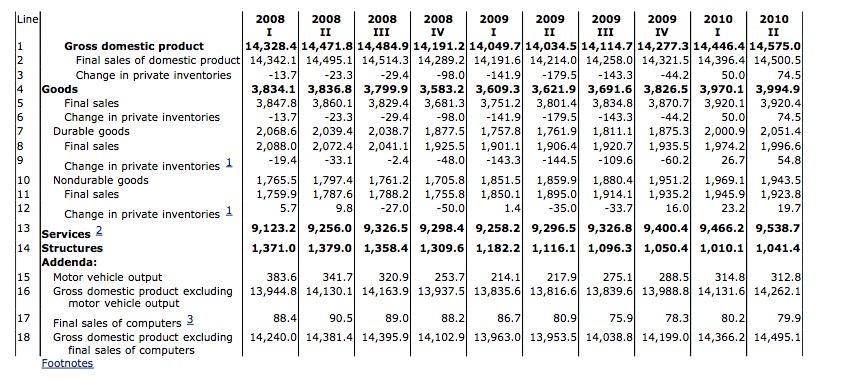

See what I mean? Of a $14.5 trillion economy in 2Q10, $9.5 trillion of that (65.5%) was services. We already have a service economy. We just haven’t adjusted our mental image of the economy yet, to fit the reality which has been with us for some time now.

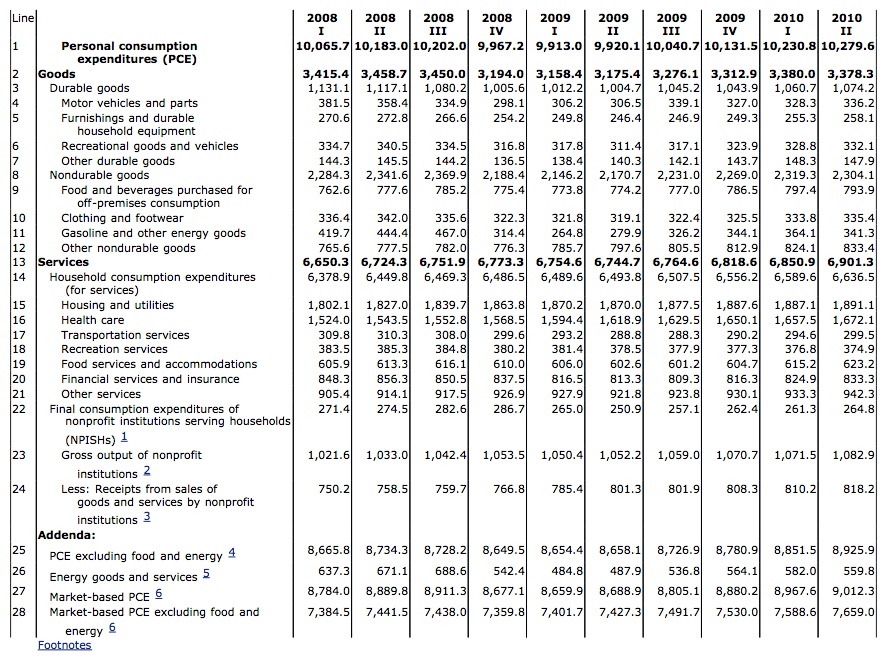

Remember, an economy is basically “what you spend your money on.” This includes government services (and goods), for which you spend tax dollars. It also includes capital investment, which is the flip side of your “spending” on savings. The rest is “personal consumption expenditures.” Here’s what they look like:

We see here that 67% of personal consumption expenditures are on services. So, you see my “service economy” fantasia is not really that weird. It would just be different services. Not so much housing, education, health care, legal and financial services, which often become parasitical burdens of contemporary life, but rather fun and enjoyable services. We could also replace some of the remaining goods with services. Trains instead of automobiles. Less spending on housing and home furnishing.

September 20, 2009: The Problem of Scarcity 2: It’s All In Your Head

September 13, 2009: The Problem of Scarcity

When I outlined alternatives to Heroic Materialism, I mentioned a “focus on lifestyle.” I like that term: “lifestyle.” It is open-ended. It could be anything. The only important thing is that you like it. You could be a ski instructor, or an artist, or an entrepreneur, or a schoolteacher. These are all different kinds of lifestyles, all with their own attractions. This is very different than the idea of a “standard of living,” which is a very Heroic Materialist concept. When we talk about “standard of living,” we start to talk about things like automobiles and televisions per capita, square feet per household member, and so forth. All these simple quantitative measures, all with the underlying assumption that More of the Same is Better. But if we don’t like what we have, then what’s the point of having more of it? Wouldn’t that be worse? I might not like that kind of lifestyle.

So, when we think of “economic growth,” we can think of an “improving lifestyle.” Sometimes, people then assume what I mean here is that “Less is Better.” Not at all. For example, if I liked performing arts, then I might think my lifestyle improved if I could afford two shows a week instead of just one. Or, if I liked skiing, I might want to ski a hundred days a year instead of just fifty. Or, if I liked handbags, I might think that a $3000 handbag was better than a $1000 one. Or, I might want to go to a $80-per-person restaurant rather than a $30-per-person one. The point is, we can think of things to do in our “lifestyle” which don’t have unpleasant consequences. I am assuming, for example, that an $80 restaurant dinner has no unpleasant consequences (such as resource use or environmental degradation) compared to a $30 one. If our entire economy consisted of things that contributed to our fabulous lifestyle, and did not have unpleasant consequences such as excessive resource use or environmental degradation, or Suburban Hell sprawlification, then we wouldn’t be conflicted about “growth.” We would be happily making our lifestyles better — or not even “better” per se, but continuing our own personal evolution towards greater sophistication, wisdom and satisfaction.

When you think about things in terms of “lifestyle,” rather than a linear measure of “standard of living” which stretches from Less of the Same to More of the Same, then a lot of possibilities open up. We could have a “lifestyle,” for example, that did not use fossil fuels at all.

May 3, 2009: A Bazillion Windmills

In that case, the electric lights in our service economy — our restaurants, schools, theaters and so forth — would be powered by solar, or hydro, or windmills or perhaps nuclear, or what have you. What’s so difficult about that? We could have as much “output” as we like — more or better restaurants, schools, theaters and so forth — with electric lights powered by windmills etc.

The process of creating this new, better service economy involves investment. We typically think of investment as building factories, buying machinery, and pouring concrete. Once again stuck in these 1950s sorts of images. We’re so beyond that now. We have more than enough machinery and concrete for every human in the United States. Actually, “investment” is just spending money, with the aim of being able to produce some useful service (or good) in the future. Thus, our “capital investment” in the future could be the process of creating more of what we want, enjoyable services, and the more investment we have, the closer we get to our goal. This capital investment is actually what creates jobs, and in fact higher paying jobs. The great growth economies, such as China today, are typified by enormous amounts of investment. In China’s case, this is “modernization” including lots of concrete-pouring and machinery-installing. However, a future “growth economy” focused on mostly nonphysical services could feature lots of investment in other sorts of things. Today, this is typified on the personal level by law or medical school, an investment in education which allows a person to provide high-value services, and thus enjoy a high income. Unfortunately, like our image of concrete-pouring and machinery-installing, this image of law-and-medical school has also been done to death. We have waaaaay too many doctors and lawyers. Instead, we need to imagine a similar process, but with other kinds of services. Try to imagine, if you can, a sort of service economy in which we have lots of investment in services, but not really this sort of doctor/lawyer/financial advisor stuff.

In practice, the “service economy” of the sort I envision tends to focus on urban entertainments. Imagine you lived in a no-car Traditional City, in a small and relatively cheap apartment. You aren’t being sucked dry by the parasitical doctor/lawyer/financial advisor/professor class. In other words, you have lots of disposable income. What do you spend it on?

Typically, you spend it on “going out.” Restaurants, clubs, cafes, bars, theaters, gyms, travel, and so forth. With a sprinkling of goods purchases, but since you don’t have a car and live in a small urban apartment, you really don’t have that much space for stuff. No boats, no motorcycles, no “media rooms,” guest bedrooms, and all that other shopping stuff. You spend some money on fancy clothes, and household furnishings — typically Less and Better rather than More and Cheaper. Just ask a French woman. And stuff like that. But, a lot of your expenditure goes to this urban entertainment-type stuff.

I’m not necessarily saying this is the best thing. It is, however, the most common thing, in history. We can see that this “urban entertainment” stuff is not really resource or energy dependent at all. You don’t need factories clanking out widgets. Paris of 1740 had wonderful urban entertainments (if you could afford them). So did Beijing of 1265. Just ask Marco Polo. So, the service economy of the future would probably be oriented more towards providing these sorts of urban entertainments, and people would be employed in providing them.

Imagine, if you can, the most wonderful sort of urban environment. Sort of like the London of the Harry Potter movies.

January 10, 2010: We Could All Be Wizards

Then, add the best parts of our Heroic Materialist advances. Things like electric lights and good plumbing, and refrigerators. You could invent a more fanciful sort of thing — like my original example of a performing-arts-centric economy — but this “urban entertainments” model is actually the typical human model throughout history, including up to the present day. This is pretty much the way forward, so that we can have “growth” without killing the planet, and in fact enjoying a much healthier environment, while also having ample employment and higher incomes. We don’t have to go with the More of the Same model, which basically amounts to More Suburban Hell, nor do we need to get in the Wayback Machine to some 19th century/18th century/12th century/Native American/Caveman model.