We live in the latter stages of the Age of Heroic Materialism. That’s the name given to this period by Kenneth Clarke, in the classic BBC documentary Civilisation. How do I know that we are in the latter stages? Because we don’t really believe in it anymore. Nobody gets a hard-on from an enormous suspension bridge the way they used to. Been there. Done that.

This is a Heroic Materialists’ idea of a good time.

Whoop de doo. That’s great — for a stiff case of road rage.

Driving on the moon!

This must have been the absolute high-water mark for Heroic Materialism. It’s been downhill ever since.

Ummm … are there any girls on the moon?

I recommend Clarke’s entire documentary, which you can get on Netflix. It gives you an idea of the entirety of Western civilisation, not just the present period. People weren’t always into Heroic Materialism.

The 18th century (just preceding the Industrial Revolution in the 1780s) was known as an age of aesthetic sophistication. The focus then was making life more artistic and subtle, rather than expressing our ability to manipulate unprecedented volumes of steel and concrete.

TWC62283

Credit: The Swing (Les Hasards heureux de L’Escarpolette), 1767 (oil on canvas) by Fragonard, Jean-Honore (1732-1806)

© Wallace Collection, London, UK/ The Bridgeman Art Library

Nationality / copyright status: French / out of copyright

PLEASE NOTE: The Bridgeman Art Library works with the owner of this image to clear permission. If you wish to reproduce this image, please inform us so we can clear permission for you.

ADDITIONAL USAGE RESTRICTION: NOT TO BE USED AS A GREETINGS CARD

Jean Honore Fragonard, The Swing, 1766.

Isn’t that a delightful image? Of course — that was their goal. To make their lives full of delight. It is a popular image for Western Civ classes to express the character of the 18th century.

I think it is important for Americans to understand at least a bit of Western Civ — our European heritage. Apparently they aren’t teaching it in college anymore.

It’s important because our American experience is much different. Heroic Materialism began along with the Industrial Revolution, around 1780. Europeans can look back at 2500 years of civilization before that time. However, we Americans have nothing before 1780. There were the Native Americans, who were admirable for many things, but we aren’t going to live in wigwams and hunt for buffalo with pointy sticks. In the American imagination, there is Heroic Materialism or … nothing. Annihilation. Total collapse. Or a “return to nature” if you want to put it in those terms. I think that’s why, when Americans look for an alternative to the industrial world, they tend to “go back to nature,” which has a strangely colonial-era feel about it. They gravitate toward log cabins and self-sufficient farms, and making your own clothes out of buckskin. It’s all very primitive.

However, the image above isn’t primitive at all. It is very sophisticated. You could find similar examples of this focus on delight and aesthetic sophistication in other cultures. For example, Japanese people had the “tea ceremony.” Most Westerners probably assume that the “tea ceremony” was some sort of religious ceremony, like the way Catholics drink wine and eat wafers in church. Not at all. The “tea ceremony” was just a super-fancy way of drinking tea. It was a nexus point that combined their various art forms into one coherent whole: tea, cuisine, clothing, pottery, architecture, garden desgin, poetry, calligraphy, pictoral art, and thrilling conversation. All taken to unprecedented levels. You could have a brief cup of tea. Or you could have an extended event that could last up to four hours, and would involve a full-course kaiseki meal followed by confections.

Tea is nought but this;

First you heat the water,

Then you make the tea.

Then you drink it properly.

That is all you need to know.– Sen Rikyu (1552 – 1591)

Who was Sen Rikyu?

Sen Rikyu … is considered the historical figure with the most profound influence on chanoyu, the Japanese “Way of Tea”, particularly the tradition of wabi-cha. …

There are three iemoto, or “head houses” of the Japanese Way of Tea, that are directly descended from Rikyu: the Urasenke, the Omotesenke, and the Mushako-jisenke, all three of which are dedicated to passing forward the teachings of their mutual family founder, Rikyu.

Of course, a “tea ceremony” with food and wine isn’t really about tea anymore. It’s just a whooped-up dinner party. Let’s try it.

“Let’s have some tea.”

“I’m hungry!”

Kaiseki is one of the most ambitious forms of Japanese cooking. It is practically unheard-of in the United States. The theme for kaiseki is many, many small dishes, served on a profusion of top-class art pottery. The idea is to have many flavors of food, and also “flavors” of pottery. I have been to kaiseki dinners where I have personally used over sixty pieces of pottery. (The dishwashing gets pretty serious.) You can’t put all those plates on the table at once, so it is served in wave after wave of tiny delights (in the most ambitious forms).

This kaiseki is from Singapore, which is why you have the “reverse roll” which you never see in Japan.

You can eat this in about eight seconds. But, it is better if you take your time.

This light lunch has twelve dishes, plus tray, chopsticks and chopstick stand.

Add tea, sake and dessert, and you can easily blow through another dozen plates.

These photos are from restaurants, so they don’t really have top-quality one-off art pottery. Unfortunately, photos of top-class pottery with food are tough to find, so you’ll have to extrapolate from these photos of pottery without food.

OK, I know you guys can look at pictures of food for only so long …

“I can’t sit like this forever. How about some sake?”

Bowls.

Plates.

A plate in the Arita (Imari) style. This is actually a hybrid: the Arita style began in the 17th century in imitation of Chinese designs, but was then tweaked for European tastes in the 18th century, when much was exported via the Dutch East India Company.

A top-class Imari plate from the 1700-1740 period, now held at the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul.

Flask and cup for wine (sake).

These “rough” styles of pottery particularly appeal to people today.

Lacquerware.

You can see that the level of artistry is much higher here than the restaurant-grade material.

“Do you think those guys are done talking about currencies yet?”

“I think they’re talking about street width now.”

“This is the most boring party ever.”

“You better not make me eat off those plates you got from Ikea.

If you do, its jeans and sweatshirts from here on out Bucko.”

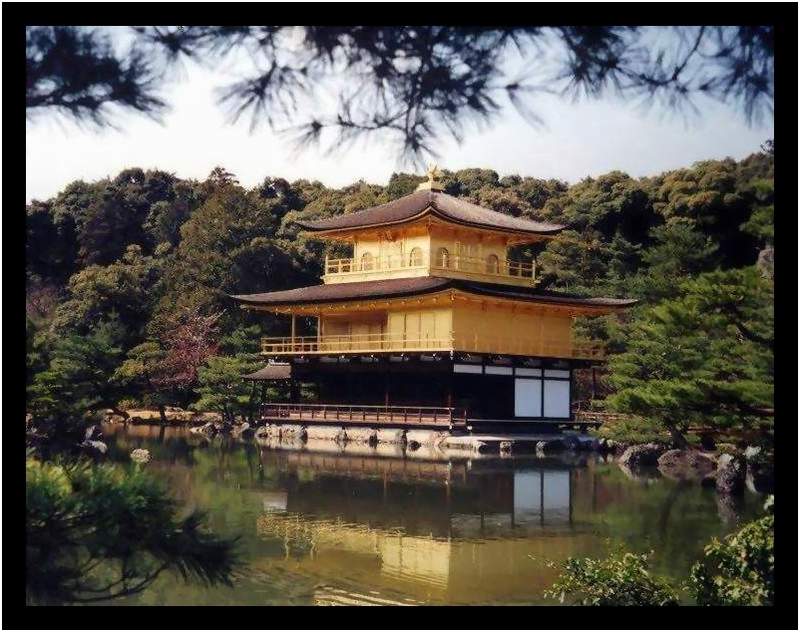

Houses and other buildings serve all sorts of functions. Sometimes you have to make compromises with practicality. The purpose of the teahouse, however, was purely for pleasure. It was their “formal dining room.” Normally, it was accompanied by an exquisite garden.

Teahouse.

This teahouse has a rock garden.

Garden seen from teahouse, Kyoto.

Teahouse in a wood.

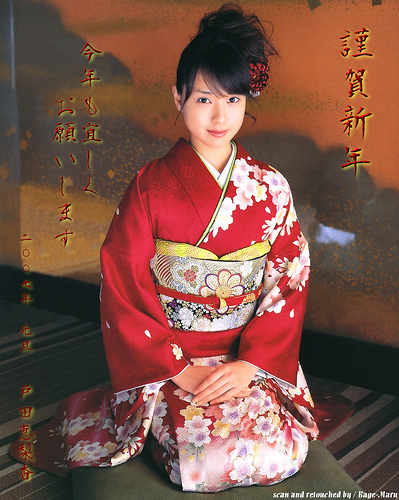

The famous Kinkakuji teahouse in Kyoto, built in 1397.

You can’t get any more gaudy than this!

At the time, it was like having a gold-plated Porsche 911 Turbo.

They were very into tea in those days.

In 600 years, maybe people will think this is the greatest existing representation of the Car Ceremony.

“If your teahouse sucks … forget it.”

“You aren’t gonna get there by making more parking lots and Green Space.”

(Actress Yu Aoi in the drama “OSen.” Good drama, by the way. We watched it earlier this year.)

This isn’t really a teahouse style, it’s a country farmhouse style. But who cares, really.

Country farmers also lived very well.

For some reason, Japanese interiors have a reputation for “minimalism.” It’s baloney.

“Japanese minimalism” is mostly an invention of New Yorkers.

They weren’t gaudy, though. They were much too sophisticated for that (most of the time).

“Now the Americans are bombing the moon? I can’t wait until those guys collapse.”

“Why don’t you carry me upstairs hmmm?”

Often, there was music and elements of visual art.

On balance, I’d say the Europeans had more sophisticated music and visual arts. But, it’s not a competition. Variety is fun.

“You have a swing?”

Teahouse, 1880s, Hakone area west of Tokyo.

Unfortunately, it is hard to find a photo that has all the elements together:

A beautiful woman in spectacular clothes, eating stunning food from top-class pottery, in a gorgeous building in a lush garden, enjoying music while looking upon ink drawings on gilded screens. With tea, of course.

You’ll just have to imagine it. Even Japanese people, although they are much more aesthetically sophisticated than Americans, come nowhere close today to the heights they reached in the past. Modernity has been tough on everyone.

The point is not that you really have to enjoy what was considered the pinnacle of sophistication in 15th century Japan. In fact, you would probably find it rather weird, and not necessarily enjoyable at all. Personally, I prefer jazz to that plinky-plinky music, and I don’t go for the traditional paste-white makeup at all. The point is that they were having a helluva time with it.

In the same fashion, we could focus our attention on artifying our lives, and come up with something completely new and utterly fabulous, instead of just making our televisions bigger and bigger and bigger.

Sometime soon (I can never finish these things in one go), we’ll have a look at the 18th-century French version of high living.

They had so much fun in those days.