What Happened to the Middle Class?

June 21, 2010

(This originally appeared in the Huffington Post on June 21, 2010.)

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/nathan-lewis/what-happened-to-the-midd_b_619200.html

If you want, you can click the link and take a look at the comments. You can probably see why I generally avoid appearing in public. It is still a little early for this sort of thing. People will need to see their civilization burn down to the ground via hyperinflation and (probably) higher taxes before they actually learn something.

In the 1930s there was a debate about whether to use currency manipulation as a means to help the economy. On one side of the debate was the classical economist, who said something like, “In the long run, you can’t devalue yourself to prosperity.” On the other side was the Mercantilist or “Keynesian” economist, who thought that a currency devaluation would help in the short term. The long run was not a concern of the Keynesian. Keynes himself argued that “in the long run, we are all dead.”

Politicians found the Keynesian stance persuasive. In 1933, the U.S. dollar was permanently devalued for the first time since the establishment of the United States in 1789. Its value fell from $20.67/ounce of gold to $35/oz. As is often the case, this indeed seemed to help, and the economy staged a recovery although the Great Depression continued on until 1940 and arguably until 1949.

In deference to the classical economist, however, the dollar remained pegged to gold after its one-time devaluation, and remained pegged to gold at $35/oz. until 1971.

Previously, we examined the history of the U.S. dollar. The “dollar” actually dates from 1513, as a silver coin made in Germany. The U.S. adopted this standard in 1789, and maintained it until 1933.

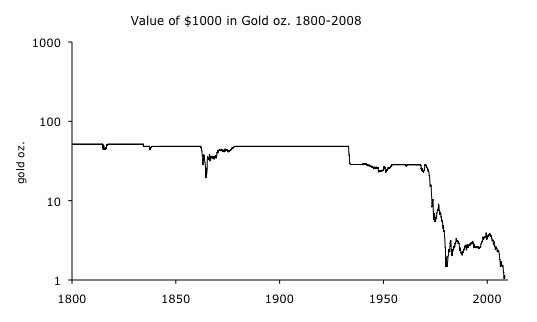

During the 1950s and 1960s, the dollar remained pegged to gold at its 1933 rate of $35/oz. These were wonderfully successful decades for the U.S., and the middle class reached unprecedented levels of prosperity. We can see here the floating currency system that was introduced in 1971.

Source: Global Financial Data

This is an inverted logarithmic graph, to show a decline in dollar value as a move in the downward direction. At $20.67/oz., $1000 was equal in value to 48 ounces of gold. Today, $1000 is worth about 0.8 oz. of gold.

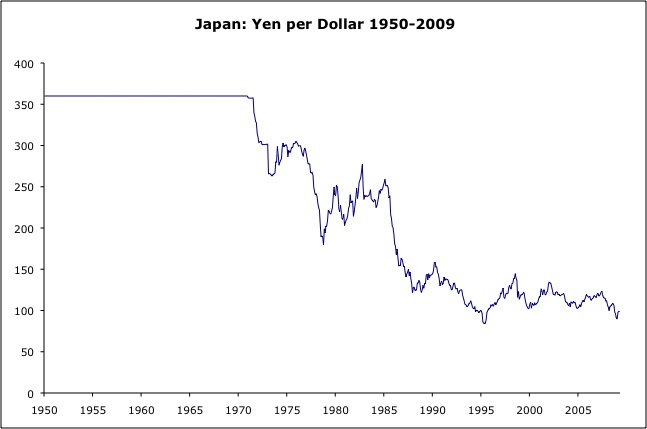

During the Bretton Woods era (1944-1971), all major world currencies were pegged to the dollar. They didn’t float. For example, here is a chart of the yen/dollar rate, which shows that the yen was pegged at 360/dollar during the Bretton Woods years.

Source: Bloomberg

However, the Keynesian money-manipulators were gaining influence. They envisioned a system where the government would “fine tune” the economy on a continuous basis, through interest rate and currency manipulation. This system appeared, as something of an accident actually, in 1971. Since 1971, we’ve been living in the Keynesian’s world of floating currencies. The classical ideal of a stable currency – a currency linked with gold – which worked so well for most of the U.S.’s history, sank into the background.

The classical economists warned that any system of currency manipulation would prevent long-term prosperity. You can’t make people wealthier by jiggering the currency. Prosperity is built on the foundation of a stable currency, which always meant a gold-linked currency.

Indeed, we find that the U.S. middle class’s long path of success ended precisely when the classicals’ gold standard system was replaced by the Keynesians’ floating-currency system in 1971.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

You can look at the same thing in terms of ounces of gold. Remember, a dollar was worth 1/20.67th of an ounce of gold for most of U.S. history. So, if a worker earned “$100 a month” in those days, in the 1880s for example, that meant about five ounces of gold. They were often literally paid in gold coins. (Five ounces of gold today are worth about $6000.) During the 1960s, “$100 a week” meant about three ounces of gold. How many ounces of gold does a worker make today?

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Kitco

This is a graph of wages for “production workers,” excluding management and income from capital. Can you see why it now takes two “production workers” per household to earn what one did in the 1960s?

This is not the only problem facing the U.S. middle class. The healthcare system has become little more than a system of extortion, and the labor/capital ratio has been badly skewed by the introduction of huge new labor pools in Asia.

However, I think that a stable currency system will be necessary if you want to return to the level of economic health we had in the 1960s – the last time we had a stable currency. Otherwise, in the long run, “we are all dead.”