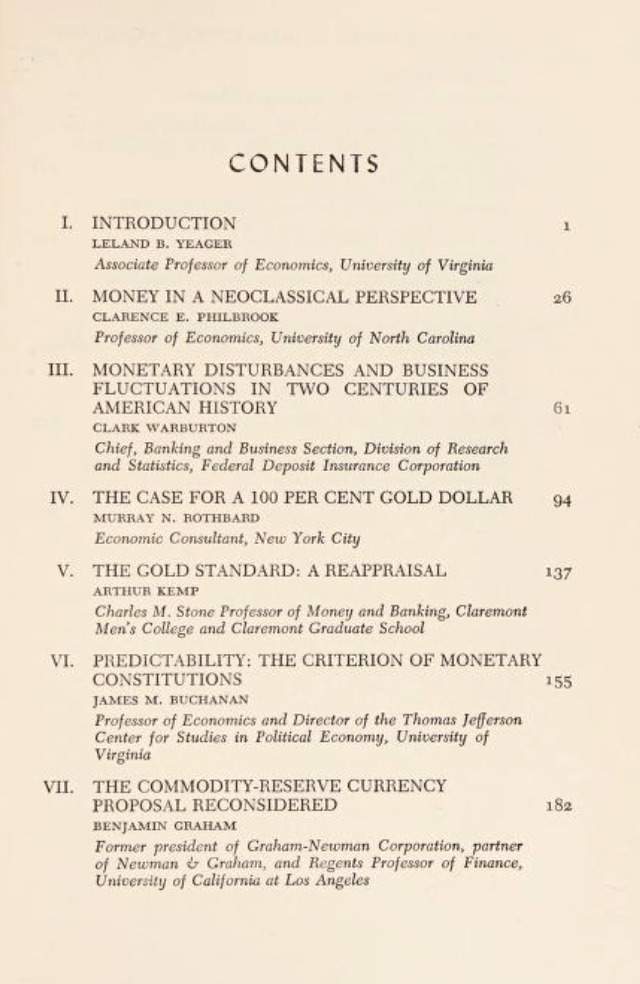

In Search of a Monetary Constitution (1962) is a collection of papers that summarized some of the more conservative-flavored lines of thinking in 1962. It is a rather depressing book, because, in the middle of an actual functioning (although substantially flawed) gold standard system, where the official policy of the Federal Reserve, Treasury Department, IMF, and the wishes of foreign governments worldwide was that the US dollar would maintain its specified value of 890 milligrams of gold (1/35th of a troy oz.) — a very explicit “monetary constitution” already in actual practice, and one that is, more-or-less, actually defined in the Constitution — there is not a whole lot of explanation of why this policy is even useful. Apparently, according to the book’s title, they couldn’t even find it! This is a very willful blindness.

I could go over this book paper-by-paper, which is not a bad thing to do, but it would mean many weeks of haranguing and complaining, and I really want to move on to Renewing the Search for a Monetary Constitution (2015), published by the Cato Institute, where my haranguing and complaining might be a little more pertinent. Nevertheless, I think this book is worth reading for people interested in the topic, not so much for its insight (it is full of error), but to get an idea of what the intellectual landscape looked like in 1962. For students, it is a good exercise to explain how the various authors got it wrong.

I have not read the book in its entirety. Honestly, I’ve heard it all before, and wrote out all the counterarguments a decade ago. So, this will be one of those “book notes” where I give something of the flavor of the book, and my reactions. This I will do by commenting on Leland Yeager’s introduction to the book, which has brief descriptions of the papers within.

Philbook’s paper, describing the “neo-classical” view, is thick with Monetarism. Apparently, this is the “neo-” part since the actual Classical economists, and their mid-20th century descendants did not concern themselves with this stuff. Ludwig von Mises did not babble about MV=PT for chapter after chapter. Adam Smith dismissed the Monetarists of his day with a single sentence.

Warburon’s paper about “monetary disturbances” is mostly about various periods of financial turmoil, and difficulties experienced during this or that institutional arrangement. Its interest in gold is mostly in the context of “gold flows” driven by “current account balances.” This doesn’t matter much, since gold is the same value everywhere. He had little to say about the only thing that is important — whether gold served adequately as a standard of value, a proxy by which to successfully achieve the ideal of Stable Value.

As a general rule, if a problem of some sort is experienced in only one country, but other countries worldwide that are also using gold as a Standard of Value (i.e., a gold standard system) are basically fine, then the problem is likely one of domestic institutional arrangements (such as led to the Panic of 1907), or bad economic policy in general in a particular country.

In the third paper, Murray Rothbard pitches his “100% gold dollar” and elimination of “fractional reserve banking” line, which is stupid of course. I think this essay also appeared in Rothbard’s The Case For a 100% Gold Dollar. As I mentioned in Gold: The Final Standard, Rothbard spends a lot of time slagging off Walter Spahr, who basically just wanted to fix the various problems in the existing system, and keep the $35/oz. peg of the time. Then there is this, in Rothbard’s paper:

I think it is interesting that Yeager, here identified as a floating-fiat guy, also supports the 100%-reserve idea. The more I think about it, the more it seems to me that Rothbard was a classic “controlled opposition” type, pitching silly unworkable solutions and actually attacking those (Spahr) with sensible practical solutions. We can debate what Rothbards motives were. But here the floating fiat guy — Yeager — thinks that Rothbard’s silly nonsense is wonderful great stuff! Makes sense, doesn’t it.

Kemp’s paper is actually quite nice, although I would say not very hard-hitting. But, he lands on many of the basic principles of Stable Money. Here is part of it:

The supply of money here is not very important. It is like the supply of meter-sticks. We wish it to be adequate that everyone who wants to use a meter-stick has one. In other words, the supply meets the demand. If there is a construction boom, and there is a great need for meter sticks, then the supply expands to meet the demand. If the boom is over, and not so many meter-sticks are needed, then the supply shrinks. The important thing is that the meter-sticks are all of unchanging length, because that is what makes meter-sticks useful.

Back to Yeager:

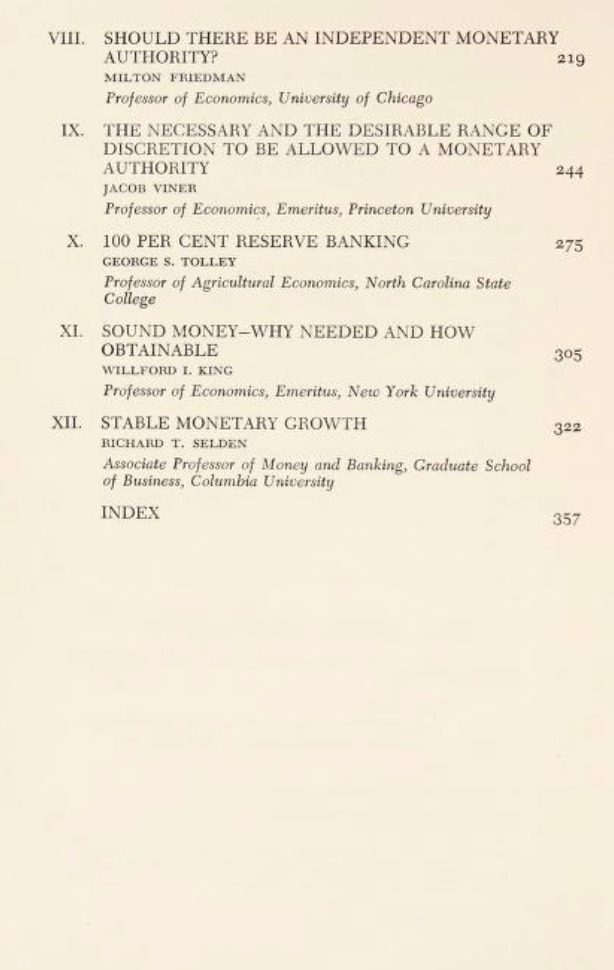

James Buchanan, who I hoped would have a good sense of these things (he won a Nobel Prize in 1986 for his work in “Public Choice Theory”), instead proposes a “brick” standard. No really, he means money based on construction bricks, which he claims is a superior solution. But, there are people like this today, who wave all the “Sound Money” banners and then propose currencies based on … aluminum. I get the impression that somebody is using the same worn-out playbook.

Graham is actually Ben Graham, Warren Buffett’s investing mentor. He really did propose a “commodity basket standard” around this time. It’s the usual commodity basket stuff.

This was the era of Milton Friedman’s Constitutional Amendment to cause the base money supply (at the Fed) to grow perhaps 3% per year. This is dumb, of course — it is basically the mechanism of Bitcoin.

March 6, 2014: Bitcoin Proves Friedman’s Big Plan Was a Joke

Friedman later abandoned this line of argument, since you can’t act stupid in public forever.

Viner’s paper makes an argument that I agree with, which is — if you start asking the Federal Reserve to do this, that and the other, it is going to be pushed toward discretionary methods. All other “rules-based” systems besides a simple value link (a gold link in the past, or a USD or EUR link today) tend to degenerate quickly into ad-hoc improvisation. Something happens, and the central banks is told to “Do Something!” And, they do. There is really only the Gold Standard (or maybe dollar or euro standard for smaller countries today, the same basic idea of a Fixed Value) and the PhD Standard, which is a constant scrum of making it up as you go along.

December 7, 2016: The Gold Standard Vs. The PhD Standard

“100% reserve banking” goes into detail about Rothbard’s various plans to eliminate banking as it has existed since the Renaissance. Banking serves an important role — it makes capital available to individuals and companies that are not able to issue debt or equity securities. There have been recent proposals for “100% equity banking,” and in fact this is the manner of Credit Unions today. This has no particular monetary component, but it does solve some of the problems of banking crises. A good roundup of this line of thinking is Jimmy Stewart Is Dead : Ending the World’s Ongoing Financial Plague with Limited Purpose Banking (2011), by Lawrence Kotlikoff. People should be familiar with it.

Any future “free banking” models, where currency is issued by multiple private issuers, should take place in a structure independent of the bank lending business, with something like 100% investment-grade securities including Treasury bills as assets.

Wilford King waves the “Sound Money” flag in his title, and then — guess what? — does the usual Monetarist bait-and-switch. His proposal is a stable CPI target, achieved by adjusting a stable-money-growth (Monetarist) tool.

Richard Selden pitches a pretty standard Monetarist stable-money-growth proposal.

And that brings us to the end of the book. What do we have here? I count only one paper, that of Arthur Kemp, which is in favor of anything resembling the actual gold standard system that actually existed in 1962 — the actual, functioning “monetary constitution” at that time. Kemp wanted a “gold coin standard,” which means that banknotes would be redeemable in gold coins, and gold coins could be and would be used in regular commerce as legal tender, although probably not very often. It would be approximately the arrangements of the 1920s. This was a nice idea, since in 1962 Americans were not allowed to own gold coins at all. Rothbard is the only other gold standard supporter, but of course his own proposals were daffy nonsense.

My impression, after looking at this book, is that we have basically the same old crap that we still have today, 61 years later. I also have the impression that this is not exactly by accident. Rather, it seems to me that certain arguments have been found effective in diverting debate away from the basic principles of Stable Money, and gold as a highly effective and time-tested way to achieve that goal. The whole thing smells of a stage-managed pageant, where the various actors have been told (or chosen) to play certain roles. Today, there are a number of institutions that cater to conservative-libertarian audiences, that consistently do the same tricks, in much the same way. Of course the Cato Institute is one of them. Maybe Leland Yeager served this role before Cato’s founding.