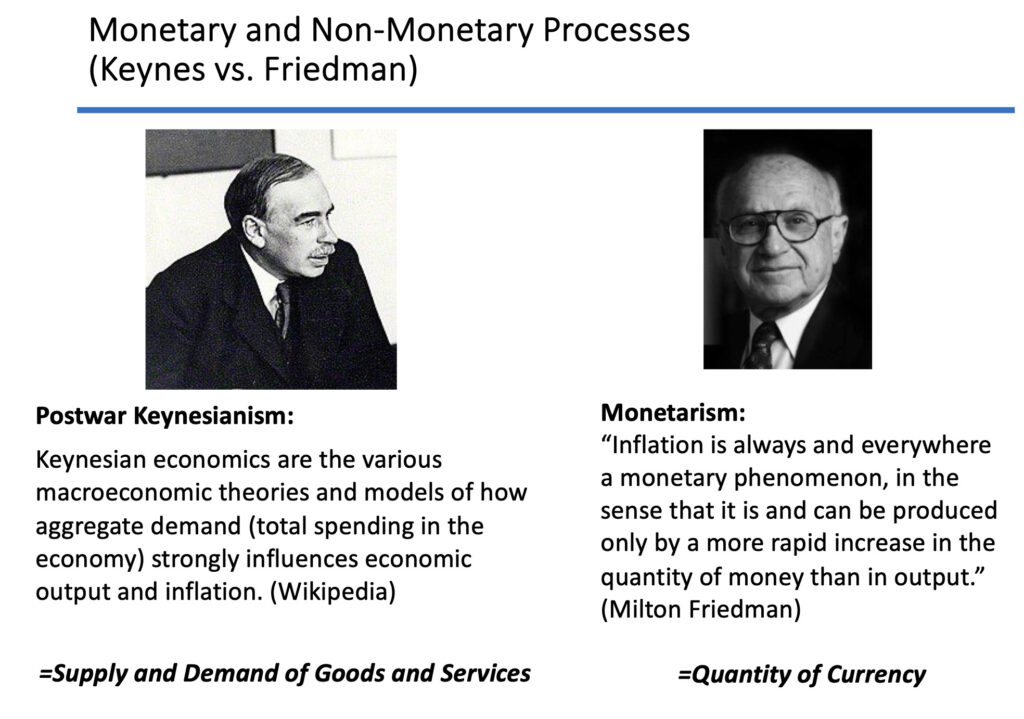

“This is why we wrote a book about inflation” has become a bit of a cut phrase for me on Twitter. One of the points in the book, which probably seemed pretty simple and innocuous at first, is that we can divide influences on “inflation” (in practice, official CPI statistics) into “monetary” and “non-monetary” categories. The first has to do with the (mis-)management of the currency by the central bank, leading to a change (decline) in currency value. The other category is everything else — which also, I might point out, includes all the actions of the financial system.

In other words, the supply and demand of currency, leading to changes in currency value; or the supply and demand of goods and services, leading to changes in the prices for goods and services, independent of changes in currency value.

To illustrate today the usefulness of this device, I will introduce two descriptions of “inflation” from reputable parties, coming after two solid years of intense discussion about the topic. Let’s see what they say.

The first is from Harvard Business Review, December 2022.

This is the basic Keynesian stance, where broad changes in the supply and demand (mostly the demand) for goods and services, in other words Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand, lead to changes in broad price measures like the CPI. A currency of unchanging value is assumed.

Alternately, we have the Monetarists’ description, where changes in the Supply of Money (Demand is ignored, or assumed to be equivalent to NGDP) lead to inflation, now ignoring all Non-Monetary factors. Here’s the Heritage Foundation:

Note that we have the usual “too much money chasing too few goods,” and no mention of changes in currency value. “We all know the driver of the quantity of money is government spending priorities …” Oh really? I guess it doesn’t have anything to do with Fed policy after all. I don’t think Monetarists would agree with that, but here, one step removed, at Heritage, apparently that is the conventional wisdom.

In short, we have this (from my recent talk at the Hillsdale Free Market Forum):

The interesting thing, for me, is that, when we started writing the book in April 2021, we anticipated exactly this discussion. Because, basically, we’ve seen this movie before. We know the errors the Keynesians and Monetarists always make.

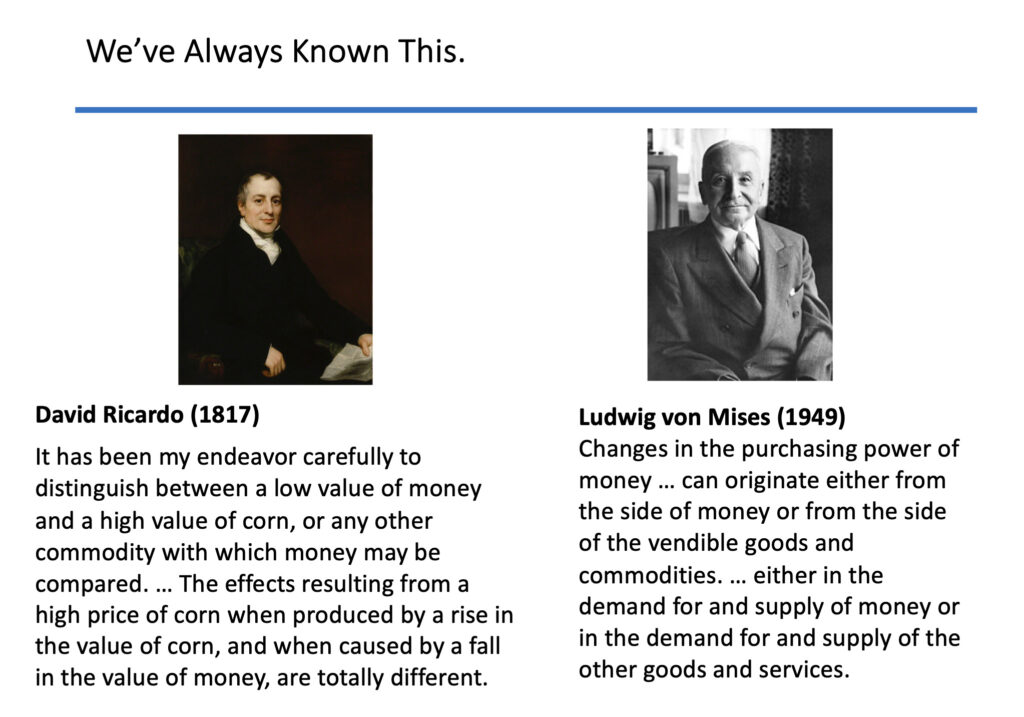

The better classical economists have always known that there are both Monetary and Non-Monetary influences on prices.

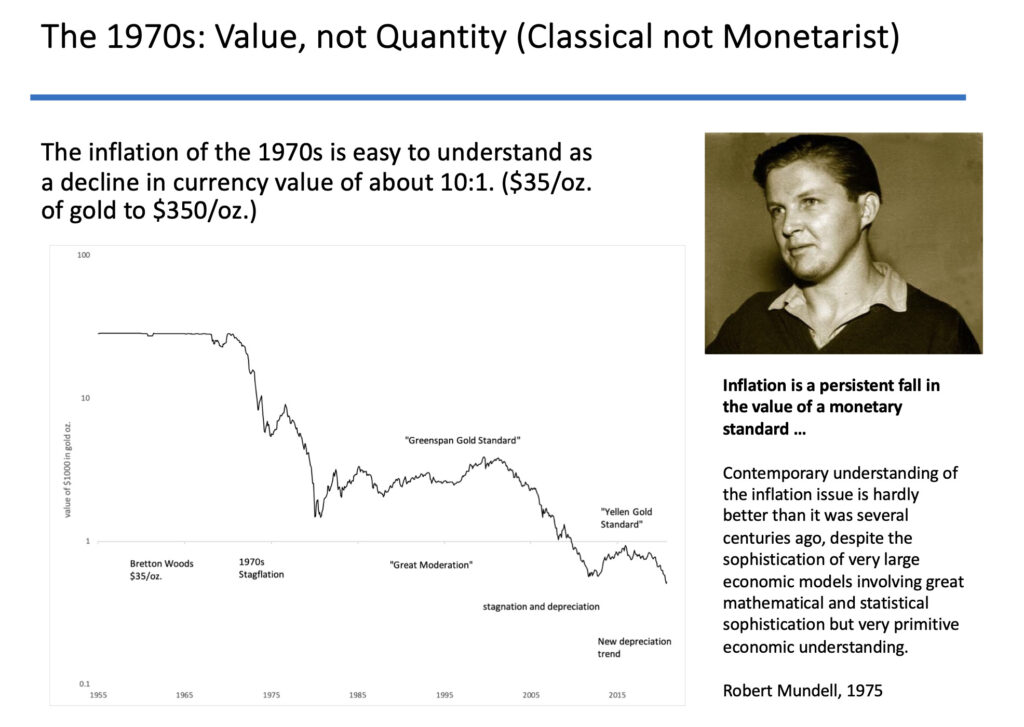

Note that Ricardo explicitly references “a fall in the value of money,” not “too much money chasing too few goods.” It’s the change in the value that causes the effect, not the quantity — although changes in the quantity can certainly affect the value, and in this case, it did. However, the relation between money supply (base money supply) and the value of a currency is not very direct at all.

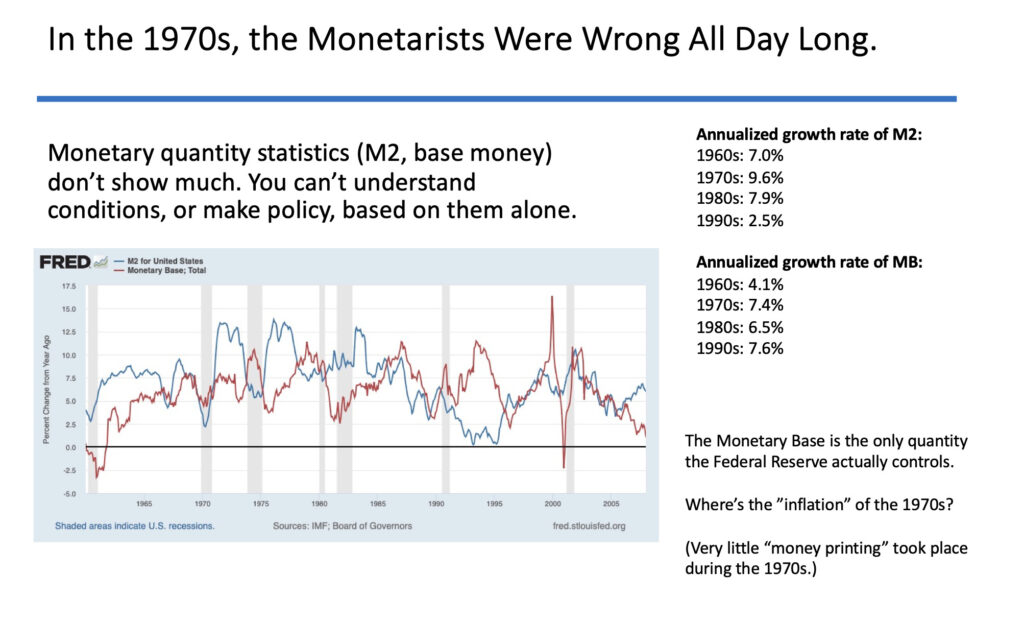

We see here that, through the Bretton Woods period of the 1960s, the inflationary 1970s, the disinflationary 1980s and 1990s, and during a new episode of currency decline in the 2000s, the growth rate of the monetary base went up and down in the single-digit range. We find that the time of lowest money growth (2000s) was actually a time when the dollar again lost quite a bit of value vs. gold, from about $275/oz. to touching $1000/oz. in 2008.

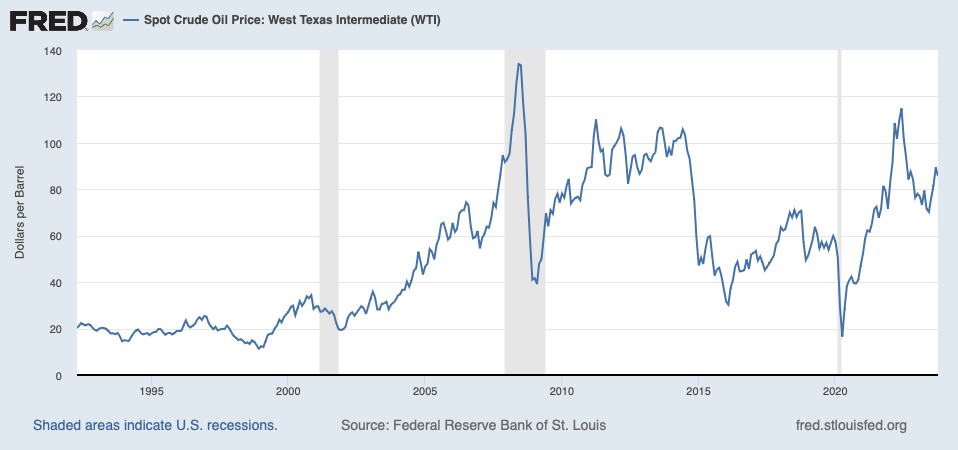

Oil prices went from an average of about $20/barrel in the 1990s to over $100/barrel in 2008, once again reflecting a decline in the value of the currency in which oil was priced.

Where is the “too much money chasing too few goods”? Hard to find, isn’t it?

And so we see that, even after two years of intense discussion about “inflation,” we are still in a condition where:

Contemporary understanding of the inflation issue is hardly better than it was several centuries ago, despite the sophistication of very large economic models involving great mathematical and statistical sophistication but very primitive economic understanding.

This is really rather pathetic, and I hope that, this time around, at least a few of the economic “expert” class will realize that you don’t have to make the same dumb mistakes forever.