We were listing some good reasons for significant tariffs.

September 22, 2024: Good Reasons for Tariffs

Mostly, this was on the topic of a certain amount of Economic Independence, often agricultural, but for the US perhaps chip manufacturing is at the top of the list today. Also, we discussed the difference between moving an auto factory from Detroit to Georgia, and moving it from Detroit to Mexico.

Today, we will talk about the fact that we live in an environment of floating fiat currencies, where “unfair advantages” and “unfair disadvantages” can easily come about due to foreign exchange swings.

On January 1, 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement came into effect, dramatically liberalizing trade between the US and Mexico.

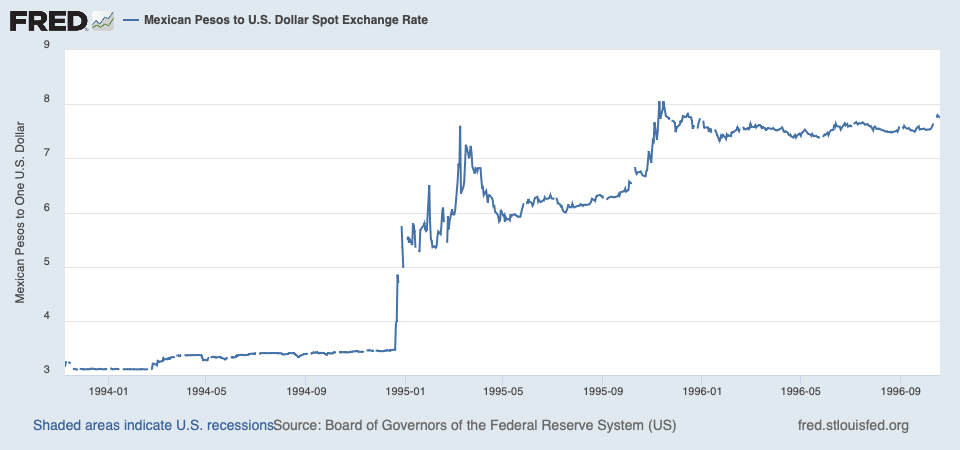

In the 1980s, Mexico had hyperinflation. Like other Latin American countries, this settled down in the early 1990s, and in 1993 Mexico had what appeared to be a reliable dollar peg, at 3.1 pesos per dollar. NAFTA was signed.

In the middle of 1994, this peg broke and the peso began to slide lower. At the end of 1994, there was a collapse, which ended up taking the peso to about 7.5/dollar in 1996.

What a coincidence! Many think it was not such a coincidence, but planned.

Many US businesses were demolished by the combination of free trade with low-labor-cost Mexico, and also, the unexpected devaluation of the peso (and, in effect, Mexican wages). In the 1992 election, in opposition to NAFTA, independent candidate Ross Perot called this the “giant sucking sound” of capital moving to Mexico to take advantage of low-cost labor.

So imagine the sucking when the peso’s value was cut in half. This was, I think, a major episode in the long deindustrialization of America, and the decline of the lower middle class.

The utility of NAFTA itself is debatable. But, I think everyone can agree that, whatever arguments can be made in its favor, are made with the assumption of stable currency values, a “level playing field.” Unstable currencies throw all this out the window.

Similar arguments were made at the World Economic Conference in London in 1933. One of the main agenda items was to roll back the worldwide tariff war that had been ignited by the Smoot Hawley Tariff in the US. But, at the meeting, Roosevelt said that he would devalue the dollar. Seeing where this was going, the other participants decided that they would keep their tariffs.

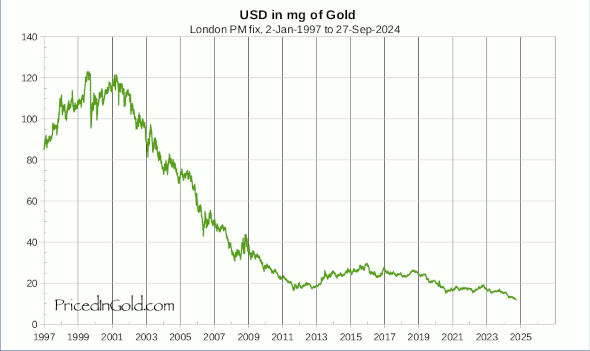

As long as you have unreliable floating fiat currencies, these issues will keep coming up — as, perhaps, they should. In the past, the world was unified with the World Gold Standard. Currencies didn’t float.

Unfortunately, this idea has been perverted over the years. Since domestic industries are always anxious to gain an advantage from foreign competition via tariffs, there arises the argument that we need tariffs — not because currencies float and maybe sink — but because they don’t!

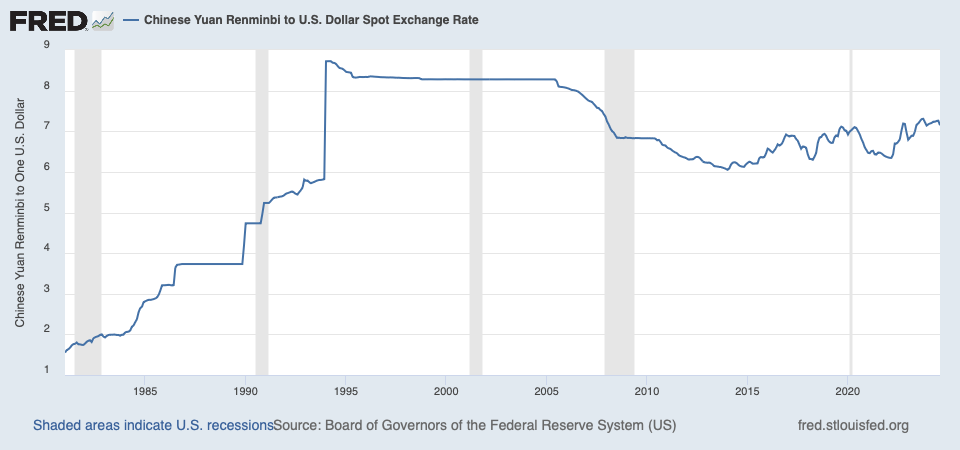

After a period of chronic currency collapse in the 1980s, China finally stabilized the yuan in the 1990s, linking it to the dollar.

Somewhat like NAFTA, you could argue, this apparent stability of exchange rates may have emboldened people to allow China into the World Trade Organization in 2001, liberalizing trade with China. It seemed like there weren’t going to be any more currency devaluations like the 1980s.

China basically had the same monetary policy as California.

The flood of cheap Chinese products that followed naturally created a major problem for domestic manufacturers and other industries. They complained, with the argument that China’s “currency manipulation” created an “unfair advantage” for Chinese manufacturers. The basic argument was that, according to some economic theory, the trade surplus generated by China’s low-cost labor should lead to a rising value of the yuan. But, the yuan was not allowed to rise, due to the USD peg. This was laughable nonsense, but it provided a cover for tariff arguments.

You can make a number of other arguments why, perhaps, liberalizing trade with China was not a good idea for the US. We will make those arguments soon. But, “currency manipulation” is not one of them.

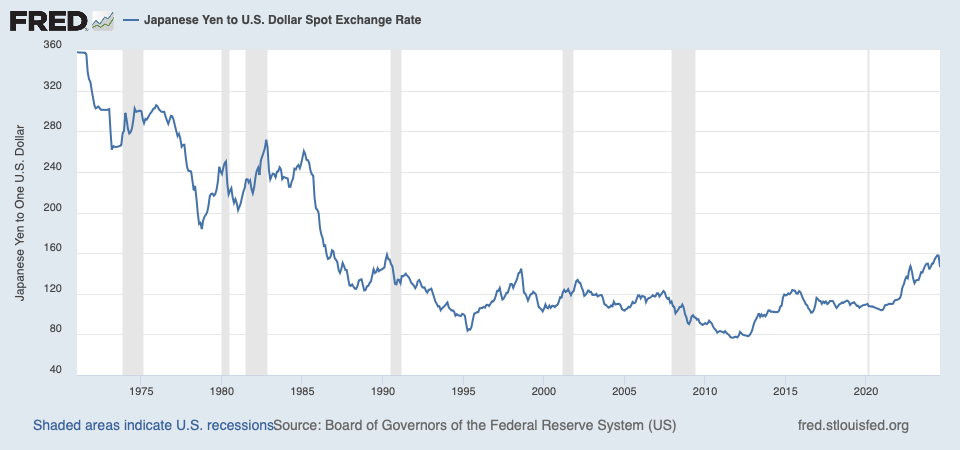

This also followed similar arguments, applied to Japan in the 1970s and 1980s. US manufacturers, notably in automobiles and consumer electronics, did not like the new Japanese competition that arose in the 1960s and 1970s. They argued that the yen should rise vs. the USD to eliminate this “unfair” advantage. Since Japan was a sort of vassal state to the US, with 50,000 US troops stationed there, this was actually allowed to happen.

This really did cripple Japanese exporters, who responded by building factories in the US — which people were pretty happy about (why is that?). So you can see why they wanted to pull the same stunt on China. China actually did allow the yuan to float slightly higher, beginning in 2005. But, this was because the USD itself was falling, compared to gold.

China did not want to be sucked into the US’s devaluation campaign, through its USD peg.

Something like a 10% to 20% across-the-board Tariff — as most countries already have, as part of their VAT — would help ameliorate the effects of at least the smaller of these forex moves.