We’ve been talking about an unhealthy admixture of Money and Credit that goes back at least to the 1913 era, and I think well before then too. There is a lot of error that arises from this. Credit is very complicated. It is a giant amount of contracts, of all different sorts. Once you start mixing Money and Credit, then you take something that might inherently be pretty simple (in our example silver coins, and silver coins alone), and then start mixing it with something that is very complicated (all the varieties of credit contracts in an economy, and all of their effects). I like to say sometimes that “credit is just people making deals.” This is a way of reminding us that we don’t really have to understand all this complexity. It is just people making deals. We should keep our eye on the Money, which in my example is literally silver coins, a very simple thing. In more practical terms, it is some money unit whose value is fixed to gold.

Understanding Money Mechanics Series

This mixture of Money and Credit has one prominent problem, which is this: It is not hard for an Authority, of some sort, to maintain a stable currency value. Historically, it just meant making coins with an unchanging amount of gold (let’s use gold now instead of silver). Basically, the Coinage Act of 1792. The coins don’t change, no matter what happens to Credit. Later, it meant maintaining the value of the circulating medium, Base Money, at an unchanging value compared to gold, which was very successful and not at all problematic during the 19th century. Since only the currency issuer (today Central Banks, historically multiple issuers but working on the same principle) manages the supply of this Base Money, we see that the currency issuer has complete control over its value. (See my book Gold: The Monetary Polaris for many, many examples).

However, once we conceptually make “money” subject to the decisions of literally millions of independent actors, all within the “credit” system, then we imagine that we lose control of the currency, and instead are able to influence it only vaguely and at a distance, through the “transmission mechanism of banks.” This is completely false, as we see today with Currency Boards which are very reliable, despite all the various contortions of Credit. Currencies are not at all subject to all the myriad complexities of Credit, but only to the reliability of the managers of that currency. But as long as this fallacy persists, people will stumble around helplessly, always blaming “this factor and that factor” (there are always a kazillion factors influencing the unimaginably complex world of Credit) for their fatalistic impotence. Nevertheless, it usually impresses people if you stand behind a podium and talk about “this factor and that factor.” Thus, central bankers’ egos are stroked, and their rewarding positions as Economic High Priests maintained, by continuing this pathetic drama.

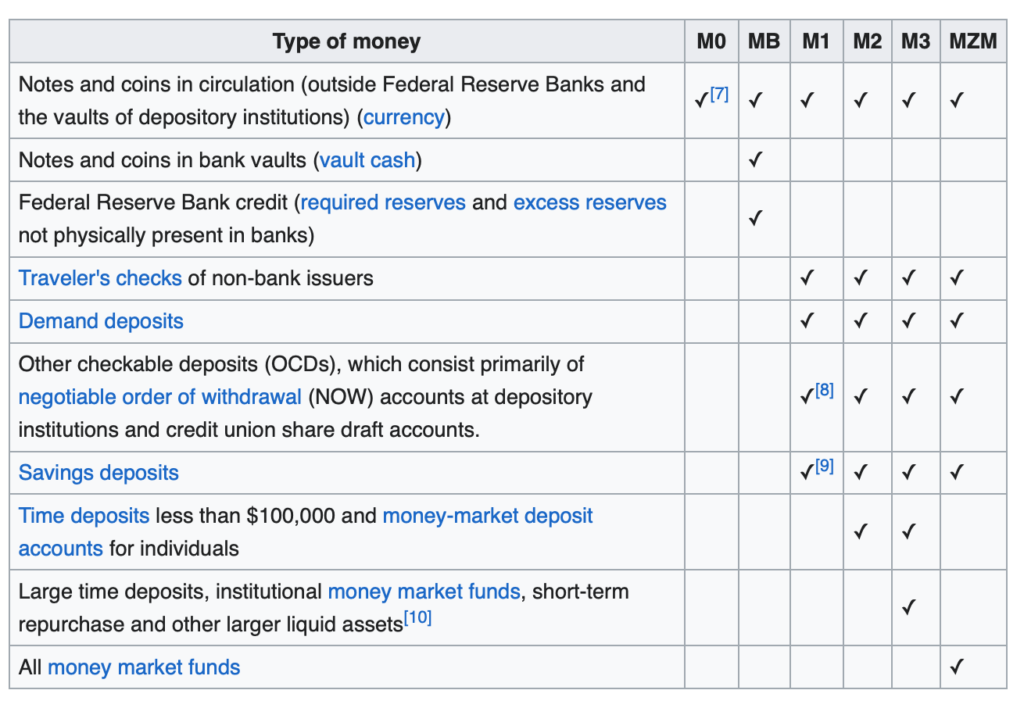

This confusion and mixture of Money and Credit turns up today as the various M aggregates, notably M2, which people seem to like. At one point, economists invented thirteen different M aggregates. M2 is:

So it is primarily Notes and Coins in circulation, and Demand Deposits. There are also Time Deposits, but only under $100,000, which makes a whole lot of sense doesn’t it. A Time Deposit is one of the most illiquid credit contracts in common use, since you can’t even sell it like a security, or redeem it like a bond mutual fund. It is absolutely not a “money substitute,” but a long-term loan. Naturally, Time Deposits are not part of M2 … unless they are under $100,000 … in which case they are. Make it make sense.

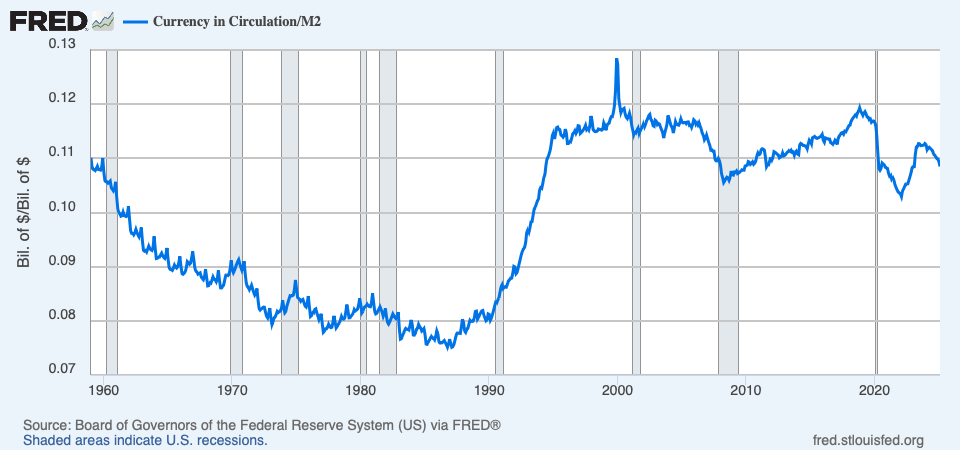

Currency in Circulation has typically been about 10% of M2, although this also goes up and down:

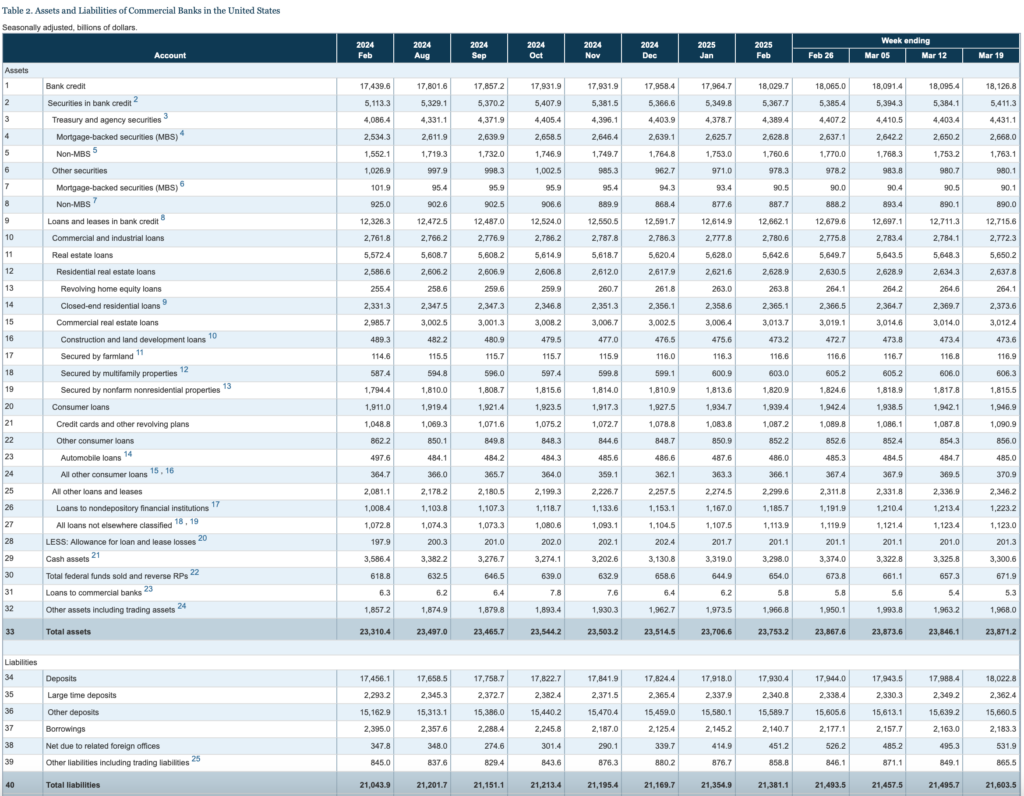

Here are the aggregate balance sheets of US banks, available as the Federal Reserve’s Report H.8:

We see that, most recently for the March 19 week, Total Assets were $23,871 billion. Cash Assets (today almost entirely Bank Reserves) were $3,300 billion, or 14%. (This includes foreign banks, which hold a much higher reserves/assets ratio as part of their global balance sheet. Domestic banks alone are around 10%.) Securities were $5,411 billion, or 23% of Assets. So you see that my basic guideline of 70% Loans, 20% Securities and 10% Reserves is just about right. Deposits were $18,022 billion, or 75% of Assets. Other Borrowings were 9%. Shareholders’ equity (capital) was $2,268 billion, or 9.5% of Assets, also right in line with my 10% guideline. These ratios have been common for banks for the last 200 years. So, you can see I am not just making stuff up.

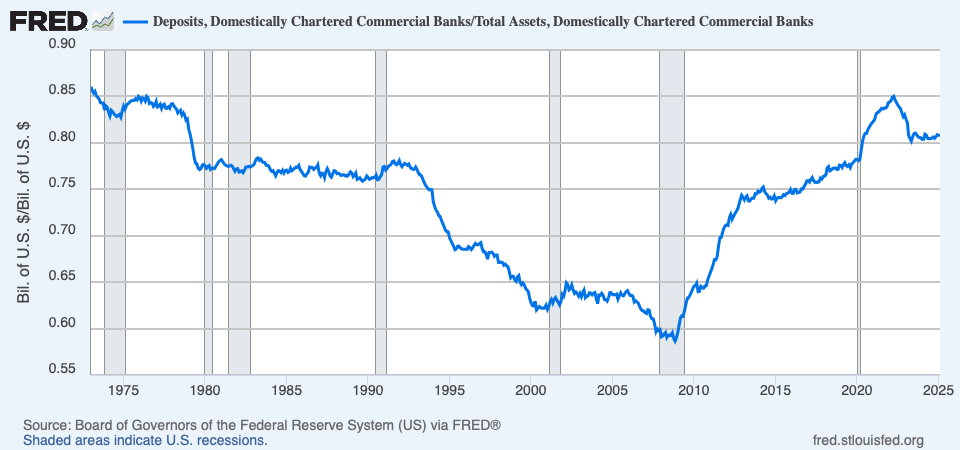

Here is the ratio of Deposits to Total Assets, going back to 1973.

It’s up and down, but around 80%, with the remainder of Liabilities basically other forms of borrowing.

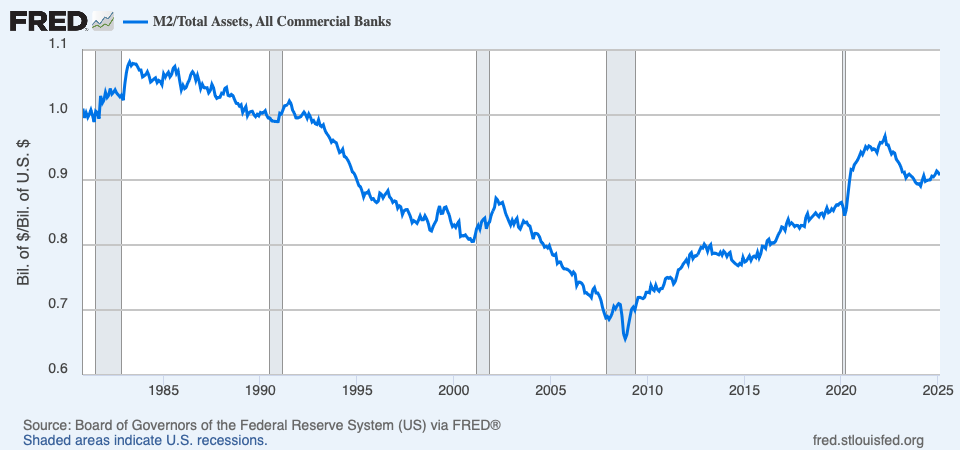

Now, if M2 is 90% Deposits, and Deposits are 80% of Assets, you probably guessed that M2 and the Assets of banks have a high correlation.

This is what I mean when I say that M2 is basically just the banking system. When banks’ balance sheets are expanding (making more loans and taking in more deposits), M2 will rise, because they are nearly two names for the same thing. M2 is the banking system.

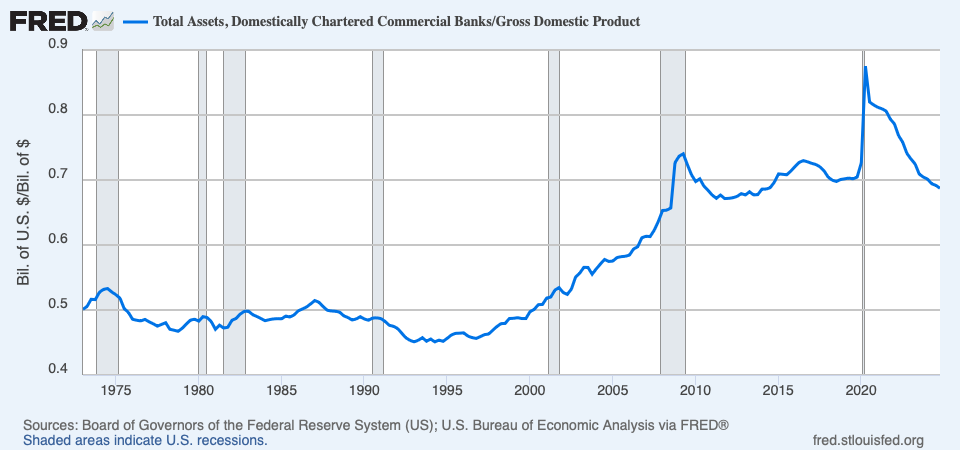

What can we say about the banking system, in general? “All else being equal,” the banking system will track Nominal GDP. Whether Nominal GDP rises due to real economic growth, or monetary inflation, we can expect the banking system to roughly expand (or contract) proportionally.

Here are the assets of Domestic banks vs. GDP:

We see that, in real life, the banking system (Total Assets of Domestic banks) maintained a roughly even proportion in 1975-2000, then had a lift higher (for some reason, it might be interesting to discover why), and then has maintained a higher plateau in 2009-present.

Also, we might expect the banking system to lead Nominal GDP by a little bit. A bank makes a loan. Someone takes this borrowed money and buys something. This purchase turns up in GDP. For example, a bank makes a loan to buy a house. This increases the demand for houses, and probably the price of houses, and homebuilders respond by building more houses. On the more recessionary side of a credit cycle, banks maybe decide that they were making way too many mortgage loans to people that were not qualified to pay them back. Underwriting standards rise, and fewer loans are made. Fewer people buy houses, maybe the price of houses falls, and homebuilders stop building so many houses. Maybe GDP contracts. All of this lending is mirrored in Deposits, since a bank requires the funding to make the loan. In any case, the balance sheet must balance. When a bank stops making so many new loans, its total lending may contract, because the principal on its existing loan book is gradually paid back as existing loans mature. This requires cash to make the loan payment, which comes from Deposits, so maybe Deposits contract. In any case, the balance sheet must balance.

Credit, including the banking system, is an important part of the economy, and an even more important part of the “business cycle” of expansion and recession, which has been recognized back into the 19th century. But, this does not inherently have anything to do with the money, which in our imaginary example was silver coins and silver coins alone, which are totally unaffected by all this (the amount of silver in the coin is unchanged, and we assume their value remains quite stable, which was long the case in the past). In real life, instead of silver coins alone you might have some kind of currency unit whose value is fixed to gold, and which thus operates in basically the same manner.

Now let’s just take this description of the banking system, M2, and call it the “money supply.” Now we can also claim that “nominal GDP is directly linked to M2,” and “economic expansion and contraction is directly linked to M2,” and it sounds like some great insight to people who are a little dumb. They also like to say that “Money is Debt!” and “Debt is Money!” which also makes people tremble with awe at their great insight, when you are just attaching the wrong names to things, calling debt money.

I mentioned earlier that the Monetarist types, which tends to also include the Austrians, tend to love this M2 because, as we have seen, the connection between the actual money supply, Base Money, the only thing that actually changes hands in a monetary transaction, and the value of the currency, or economic performance, or the CPI (part of Nominal GDP), is not linear at all. Of course they are connected, but not in the kind of mechanistic way implied by “MV=PQ.” We also saw that they are kind of stuck in this “MV=PQ” rut because literally their definition of inflation is “an increasing supply of money,” with no reference to the value of the currency. Of course if that is the fundamentally incorrect “definition” you begin with, then you will become very, very, very interested in the “money supply,” and since you are so interested in it, you will want some kind of “definition of the money supply” such as M2 which is highly correlated to nominal GDP. In time you will come to love and adore this high correlation, and in fact tendency toward causality since bank lending expansion or contraction does tend to precede, and cause, economic expansion and contraction. It will seem like you have discovered some kind of amazing insight.

But, all that you are really looking at is the expansion and contraction of the economy. We already know that economies expand and contract, and that the “credit cycle” (including bank’s balance sheets) is an important part of this. Basically you are diagnosing symptoms as causes. “He’s sick because he has a cough and a fever.” My what insight you have there. A lot of 20th century economics consists of this sort of thing. On the Keynesian side of the aisle, we have “recessions are caused by a decline in aggregate demand,” which is basically just the typical symptom or feature of a recession. It just means, “there’s a recession.”