The Service Economy

May 16, 2010

What an economy is and what people think it is can be very different.

An economy’s purpose is to produce something of value for its participants, i.e. people. Thus, an economy’s purpose is mostly to create end products and services. An end user can’t do anything with fifteen tons of steel girders, or a commercial-grade database system. These things are part of the process of creating an end product or service, like a building or a functioning retail store. I say “mostly” because among things of final value are things that fall under different categories, mostly government services. Things like roadways or sewage systems, or the military.

Thus, the economy’s purpose is to make the things you spend your money on — either directly, or indirectly via taxes which fund government products and services.

May 5, 2008: What Is the U.S. Economy?

Ultimately, there is only one world economy. However, we usually think of the economy of some region, like a city or a country. This region will typically have some trade with other regions, and thus the product of that region’s economy may not be used in that region. For example, Korea makes a lot of ships. These ships are not used by Koreans, as end products or services or even as part of the mechanism of producing end products or services, but rather as trade goods. The ships are ultimately traded for some other products or services.

This is one reason why people don’t see the link between what they buy with their money and the “local economy.” The “local economy” might be based on shipbuilding, but nobody is buying ships in the store. However, these things cancel out on the aggregate level, and all products and services of the economy are used (“consumed”) by participants in the economy.

If you want to understand what the economy today produces, simply look at what you spend your money on. Most people spend most of their money on housing, transportation, education, and medical care. By “housing” I include all expenses associated with housing, such as furnishings, insurance, landscaping, maintenance, and so forth. I would also add to “housing” utilities expenses that are housing-related. For example, home heating is directly related to the type of structure, while phone and internet connectivity is not. Transportation of course means automobiles in the U.S., and all related expenditures such as insurance, maintenance, fuel, parking, highway tolls and so forth. Expenditure on education and medical care is not so obvious, because it is often paid by employers or the local government. Think about what local governments spend your tax dollars on. Except for graft, theft, debt service and so forth, it mostly goes to education, health care, and housing/transportation-related items like roadways and sewage systems.

In general, I find the U.S. economy (and most developed-world economies) are rather grossly overweighted towards goods rather than serivces. We have developed a lifestyle pattern that requires or encourages quite absurd amounts of things. I’m not talking about your clothes closet. I’m talking about the biggies: housing, cars, and housing/auto-related infrastructure, including roadways, parking lots, garages, Green Space, and so forth. And all the stuff that goes to fill up those big houses. What we call Suburban Hell. Our “productivity” is directed toward building Suburban Hell and living in it.

I have been suggesting a lifestyle that has much fewer goods — the Traditional City. Although the goods are much fewer in volume, their quality tends to be much higher.

March 14, 2010: The Traditional City: Bringing It All Together

Perhaps one reason that Americans in particular have developed this strangely goods-intensive lifestyle is that we have a mental image that an “economy” means making goods. Factories. Churning out goods.

Before the Industrial Revolution, people had the image that an “economy” consisted mostly of agriculture. Merchants and craftspeople (there weren’t “factories” in those days) were considered marginal economic actors. Wealthy people were those who had amassed large tracts of land.

During the Industrial Revolution, merchants and craftspeople got a bit more respect, and we have an image that migrates toward the “factory” ideal.

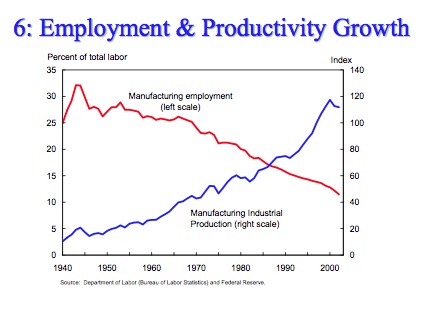

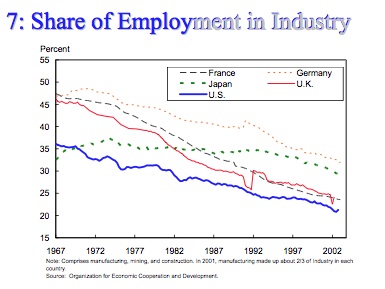

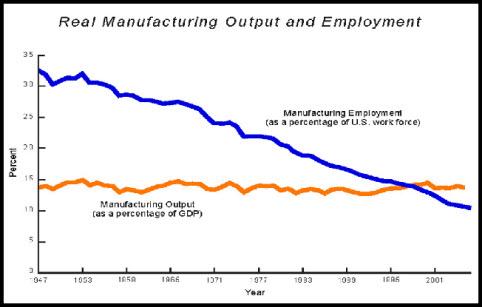

Just as increasing agricultural productivity has allowed us to feed ourselves with only a few people engaged in food production, thus the U.S. economy’s manufacturing component is also performed by fewer and fewer people.

A developed economy can have a lot of manufacturers, but they are mostly manufacturers of capital goods and industrial products, rather than consumer goods. For example, the U.S. economy produces things like airplanes, military equipment, all sorts of information technology stuff like fiberoptic cables and related electronics, equipment for plant construction whether a sewage treatment plant, a chemical factory, or oil and gas-related equipment, medical equipment and pharmaceuticals, electric power utility equipment, and that sort of thing. None of which you’ll find at Wal-Mart. Most people “can’t see it.” But it’s there.

Actually, manufacturing, as a percentage of U.S. GDP, has been pretty flat since 1947. The difference is that it takes many fewer people to do it. Just like agriculture.

You can only eat so much food. So, as agricultural productivity increased, it took fewer and fewer people to make plenty of food. All those former agriculturalists needed a new profession. They became factory workers. This was a good thing, because now we had not only food, we had food plus the output of the factory workers. We became more wealthy.

Maybe you can only consume so many goods. We’ve certainly done our best. As manufacturing productivity increases, it takes fewer and fewer people to make goods. All those former factory workers now need new jobs. An economy is “goods and services.” So, if you aren’t going to make goods, you can make (“perform”) services.

Many “goods producing” industries are not even categorized as “manufacturing.” The main “goods” being produced are buildings and urban infrastructure (roadways, parking lots etc.).

Let’s try to imagine an economy — a lifestyle — that is much less goods-intensive than Suburban Hell, and much more service-intensive.

I think it helps to imagine economies in the form of “lifestyles.” That’s what an economy is — the means of producing the “lifestyle.”

Let’s imagine a sort of idealized Traditional City urban lifestyle. You live in an apartment which is modest by Suburban Hell standards — let’s say 600-1200 square feet. You don’t own a car, but use the ample and wonderfully efficient train system. (Occasionally, you might rent a car for a weekend.) You don’t have a yard, or a media room, or a guest bedroom, or a breakfast nook, or an exercise room, or an attic, basement, garage and so forth, so your needs for home furnishings are much less. Since you have only one modest living room to decorate, you have high quality artworks and artisan-quality home furnishings. Your utility consumption is much less, because you only need to heat a modest, well insulated space, not a huge McMansion. Your closet has a modestly-sized collection of artisan-quality clothing, rather than three hundred t-shirts from HMV.

There are a couple things going on here. First, your consumption of material things is obviously much, much less than the typical resident of Suburban Hell. However, each thing is rather nicer, what I call “artisan-quality.” In turn, this means that we can have an economy of artisans, of small-scale craft, rather than huge sweatshops churning out bottom-quality junk.

If you aren’t spending your money on stuff, what are you spending your money on? Services! Vacation and travel, restaurants, clubs, music and theater, cafes, day spas, personal trainers, therapists, education and training, and so forth.

These are typical services. We can note a few things. First, they are almost completely non-material. The primary “resource consumption” for these services is mostly commercial real estate — a place for the service to happen. Second, they can expand to almost infinite degree in money terms. For example, the services rendered to Eliot Spitzer just before he became the former governor of New York were apparently billed at around $5,000 an hour. Spitzer apparently preferred to spend his money in this fashion rather than buying 2,000 t-shirts from Old Navy on sale, or burning up 2,000 gallons of gasoline cruising across the landscape with a Corvette. However, we see that these services had almost no resource component. We can also see that the scope of expansion of these (and many other) serivces is practically unlimited. There are no resource constraints when you don’t use any resources.

We have another emerging theme here: that of quality instead of quantitiy. One of the themes of the age of Heroic Materialism has been quantity over quality. There was no lack of quality during the preceding 18th century period. Their craftsmanship was outstanding. Their architecture was sublime. There just wasn’t very much of it. Only aristocrats could enjoy these things. A great many people had almost nothing at all. An idea from the Heroic Materialist age was that of the “standard of living.” The “standard of living” consisted almost entirely of quantity — things like washing machines per capita, that sort of thing. Now even very poor people have washing machines. We have so many washing machines, that people throw out perfectly functional ones just so they can buy one that looks a little better. You can get washing machines for free, or nearly so.

However, the service economy is more about quality. For example, a person working all day can make hamburgers at McDonalds, or they can make wonderful food at a nice restaurant. The wonderful food costs a lot more. It has higher value. However, there is about the same amount of it, or perhaps less. The path of “growth” in the service economy is less quantity and more quality. This is the opposite of the typical manufacturing pattern, which is less quality (or at least a lower price for the same quality) and more quantity. The typical path of “growth” in manufacturing has been more stuff at a cheaper price, which not only has natural resource issues, but exacerbates them.

You can think of an economy as a big pile of goods and services. The bigger you make your pile, the wealthier the economy. Even bonehead academic economists agree that economic development and wealth is related to productivity. You can’t consume goods and services unless you have the ability to make them.

Let’s take an economy of ten farmers. Farming productivity is low, so it takes lots of farmers to make enough food to feed everyone. They don’t have a lot of material goods, because there’s nobody to make them. Presumably they hack together some rudimentary shelter in their free time left over from farming. Their pile is very small. (However, they may have abundance, because their perceived needs are very small too.)

Then, farming productivity increases. Now there are three farmers and seven manufacturers. The pile is bigger now, because it has the products of farmers and manufacturers.

Then, manufacturing productivity increases. Now there are two farmers, three manufacturers, and five service providers. The pile is bigger yet, because it has the products of farmers and manufacturers and service providers.

The “size of the pile” is GDP. It is not the physical size of the pile, but the money size. The money size is roughly goods/services (quantity) X price per goods/service (quality).

Thus we can see that if we make things of higher quality, the pile “gets bigger.” In money-market-economy terms, “quality” is generally indicated by “price.” A Hyundai Elantra and a Mercedes SL500 are virtually identical in physical/resource terms. The difference is “quality.”

Let’s go back to our farmers. As the Industrial Revolution progressed, and agricultural productivity increased, fewer and fewer farmers were needed (at least as a percentage of population) to make food. This is “unemployment,” more or less. The farmers ended up in factories or other urban pursuits, and the cities grew.

We consider this something of a success, particularly during the 1950-1960 period, because there were “good, high-paying factory jobs.”

Where did the factories come from? They came from capital investment.

The difference between a “high-paying factory job” for a former farmer, and a job pushing a broom, is capital investment. During the Industrial Age, this capital was invested in factories. The increasing productivity of manufacturing was achieved by mechanization. This is where the high wage came from. A single workman could make a whole lot of stuff because of high productivity. The revenue-per-employee was high. This is different from low-paid sweatshop labor, where there is low capital investment, and the revenue-per-worker is low.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that jobs which are exposed to low-wage foreign competition are at risk. Most better-paid jobs in the U.S. are the ones that are non-exportable, either because of geographical issues or because of technology/skillset issues. Manufacturing employment is struggling in the U.S. because of the competition with cheap foreign imports — first — and second because those industries where the U.S. has a competitive advantage (mostly complex capital goods) are also experiencing productivity increases, so it takes fewer people to create the same output.

The path toward high-paying service jobs is also capital investment. When the revenue-per-employee is high, then employee wages are also high.

Doctors get paid more than home nursing helpers. This is because doctors have more capital investment (medical school), and are thus able to produce services of higher value. Capital investment in the service economy often takes the form of education and training, not the creation of some giant machine to make manufactured products. Lots of service economy occupations are in things like hotels, restaurants, cafes, bars, clubs etc. Just think of how much money the typical urban dweller can spend in these places. (I think many urban dwellers can spend half their income in this way.) It doesn’t have to be technical training like a doctor. We all know the difference between a good restaurant and a bad one, or a good bar and a bad one, or a good hotel and a bad one. The best are much more expensive than the worst. What is the difference between them? The physical building itself is a biggie. A fine hotel is defined not so much by the skills of the staff, but rather the building. Also, a nice restaurant usually has excellent decor. Thus, one way toward “greater productivity” in services is not “investing in a big machine,” but rather “investing in really great architecture/decor.” The result of investing in architecture/decor is the same in the service economy as investing in a big machine is for the manufacturing economy. You end up with higher revenue-per-worker, or higher productivity. The end result (the hotel service) is better, and thus more valuable.

There are many other services where education and training are the primary “capital investment.” Marriage counselors, divorce lawyers, accountants, interior decorators, yoga instructors, musicians and other performers, and educators of various sorts. Just think of what services you spend your money on.

In all economies, “growth” tends to be related to capital investment. You invest capital to become more productive. This is often a hit-or-miss affair, but on balance the result is increasing productivitiy. Without this capital — in a capital-starved economy — you tend to have lots of low productivity, low-wage jobs. In manufacturing, this is the “sweatshop.” In the service economy, it is low-wage broom-pusher/landscaping/big box retail/burgerflipper type jobs. With this capital, you have high productivity, high wage jobs.

March 30, 2008: The Capital/Labor Ratio

As more and more of the labor pool is absorbed by these high-productivity, high-wage jobs, wages for low productivity jobs can also increase to the extent that the available labor is constrained. Somebody has to clean the toilets. If there’s nobody who wants to do it — because they have lots of education and training, and thus other options — then wages have to rise until someone eventually volunteers to clean the toilet. You can’t export toilet-cleaning to India. However, if immigration policies etc. result in an abundance of available labor for these low-productivity unskilled jobs, then wages will remain low.

Sometimes, purveyors of low-wage labor say that they need immigrants because “Americans won’t do these jobs.” Americans would be happy to do those jobs, at the right price. I guarantee there would be plenty of Americans happy to pick oranges at $35/hour.

Thus, the path toward a successful service economy is much the same as the path towards a successful manufacturing economy — lots of capital investment. Instead of factories, machines and automation, the service economy tends toward architecture and decor, and education and training.

Many “sustainability” types casually equate the “economy” with resource use, in a sort of 1:1 ratio. A growing economy must consume more resources, and less resources means a shrinking economy. Actually, a growing economy means that the goods and services being produced have a higher monetary value. It has nothing to do with resources. That’s why I say that we could have an economy based on performing arts, if that’s what we spent our money on. We would have a “performing arts lifestyle,” and an economy to produce this lifestyle. Instead of building and maintaining Suburban Hell, we would be directing our productive capabilities toward performing arts. Maybe it would be like the Romans and their baths. We would take every afternoon off, and go listen to live music. Instead of spending our income on houses and cars, we would spend it on performances. If our “productivity” increased — if we had better performances per performer — then we would have “economic growth,” with no resource use. How would we arrive at this “better performance”? Perhaps through education and traininig — in other words, capital investment.

We have one farmer, two “manufacturers,” one construction person, two service people, and four performers. Our “pile” of goods and services would be 40% performing arts. This is rather fanciful, but it helps to get people out of the “resource dependency” mindset. Think of it like a lifestyle. If you have an eco-friendly lifestyle, then you would have an eco-friendly economy. If you managed to improve your lifestyle — whatever that means to you — then you would have “economic improvement,” or “economic growth.”