(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on April 6, 2018.)

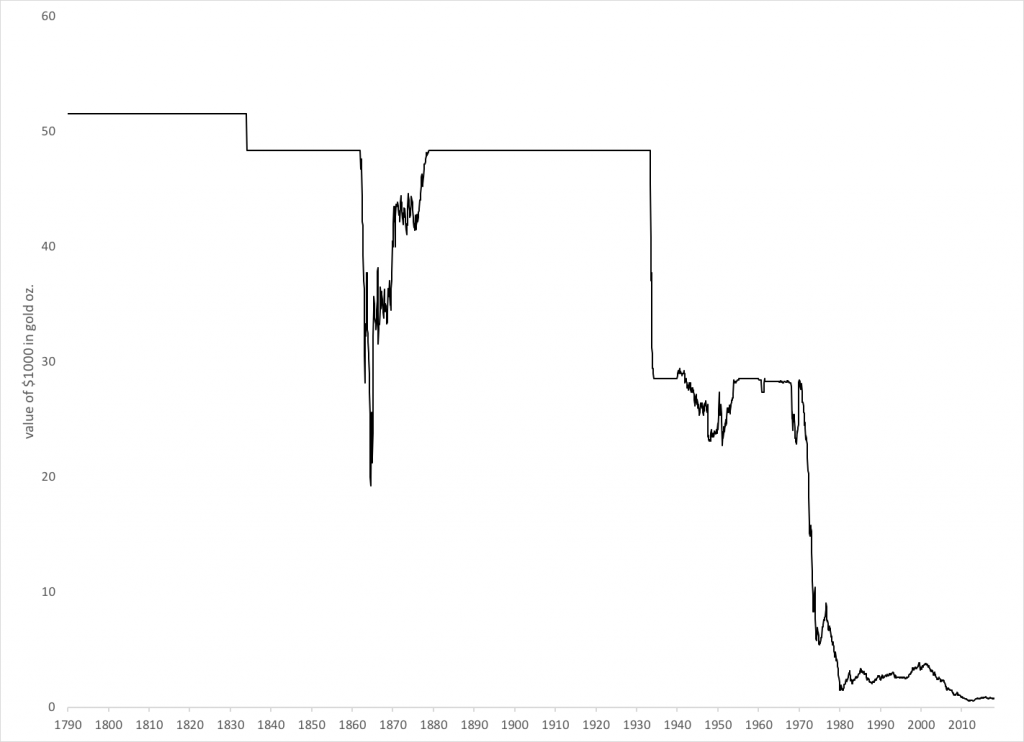

The value of the dollar was linked to gold — that is, the U.S. used a “gold standard” — for most of the time between 1789 and 1971, a stretch of 182 years. From 1789 to 1933 (ignoring for now a minor adjustment within the bimetallic system in 1834), the “parity value” was $20.67/oz. From 1934 to 1971, the parity value was $35/oz. In other words, the dollar’s value was to remain stable at 1/35th of an ounce of gold. Other major currencies — the British pound, French franc, German mark, Japanese yen, and many others — followed a similar policy, with the result that exchange rates were also fixed and unchanging.

For much of the past five centuries throughout the Western world, this was “normal.” The floating currency environment we have today, which academic economists like to suggest is some kind of natural economic phenomenon, is actually an aberration. The dollar’s value has declined to about one-thirtieth of what it was in 1970, compared to gold, with predictable consequences. If the next fifty years are no better than the last, the dollar will be worth no more than a thousandth of its value during the Kennedy administration.

Is this what a great nation does? The historical record is clear: this sort of thing has been done by many great nations, in their “decline and fall” phase.

In 1984, the remarkable Congressman Jack Kemp introduced the Gold Standard Act of 1984, which was cosponsored by seven others including Newt Gingrich and Connie Mack. It didn’t pass. In March of this year, 34 years later, Congressman Alexander Mooney (R-WV) introduced H.R. 5404, “a Bill to define the dollar as a fixed weight of gold.” Mooney also wrote an op-ed about it for the Wall Street Journal.

A dollar relinked to gold was always part of Jack Kemp’s “supply side” vision. In those days, I think most people couldn’t make much sense of what he was talking about. That seems to be changing today. I am seeing more interest in the topic among younger people; and not only more interest, but also more sophistication. This item from FTAlphaville’s Matthew Klein, asks a question that I like to ask too: if it’s OK to link over fifty countries’ currencies to the euro, why not to gold? Well, obviously it is not only “OK,” the results can be quite fabulous, as the wonderful Classical Gold Standard era of 1880-1914 demonstrated so well. The euro is on the “PhD standard,” which, in all of known history, has never been able to outperform the gold standard.

For the 1980 presidential election, Ronald Reagan recorded a television commercial promising to return the dollar to its golden anchor. The ad didn’t run, and for a long time it remained little more than an urban legend. In 2016, the Lone Star Committee managed to find the original, and used it as part of a television commercial in support of Ted Cruz.

Monetary issues are not front-and-center at this time, in no small part because we haven’t had any big problems. The “Yellen gold standard” kept things tolerably stable — perhaps in small part due to the group of gold standard advocates who, in a private meeting with Yellen in 2015, explained why Alan Greenspan says he considers gold to be a primary monetary indicator.

I think we are building a foundation of expertise — expertise that we didn’t have in 1980 — that will allow us to restore the United States’ long tradition of gold-based money, when the political time is right. My own book Gold: the Final Standard came out last year, completing the “gold trilogy” that includes Gold: the Once and Future Money (2007) and Gold: the Monetary Polaris (2013).

Eventually, someone like Alexander Mooney will introduce a bill like HR 5404, and it will pass. It will pass because it is the right thing at the right time; and also, because we have the confidence that we actually know how to do it.