(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on January 15, 2020.)

It seems to me that we are in the waning days of Keynesianism. On the one hand, people want to push their Keynesian tricks to the limit; on the other, people sense that it isn’t really working. One leads to the other — it doesn’t work, so we do more of it. This might lead to one of two outcomes: we get tired of the charade, and it peters out as we go in a new direction. Or, we double down on stupid, and it blows up in our face. Either way, the Keynesian Age comes to an end, and we begin the next thing.

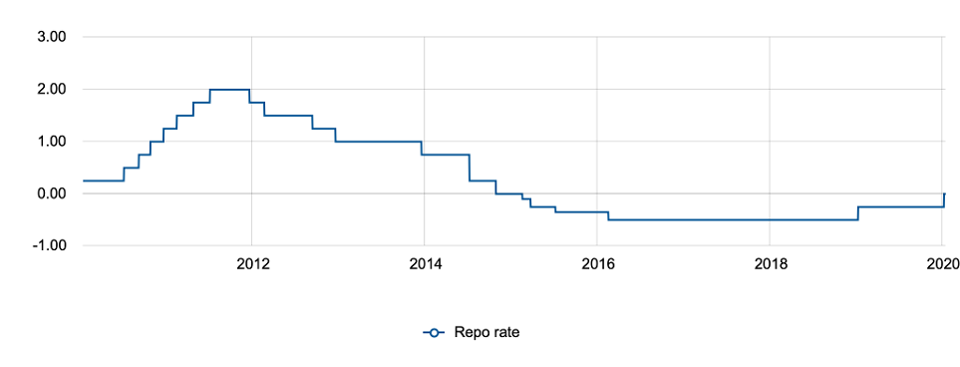

“Keynesianism” can be boiled down into two things. One is monetary and financial manipulation via central banks and floating currencies. The “monetary” aspect has to do with the floating value of the currency; the “financial” has to do primarily with interest rates. They are intertwined. In the past twenty years, we’ve tried both aspects: there was a big depreciation of currencies worldwide in 2001-2011, which was basically in response to the recession of 2001 and the financial crisis of 2008. Along with this, and especially since 2015, there has been experimentation with low interest rates, even negative interest rates, which have never before been seen in human history, on a broad and sustained basis, until this time.

The other aspect of Keynesianism is basically government spending. While there are often worthy things for the government to spend money on, the “Keynesian” framework asserts that spending itself is some kind of economic benefit, even if it produces nothing of value and is a total waste. This has been tried many times since 1930, and was generally considered a failure. Japan’s unsuccessful attempts to use it to revive its economy in the 1990s were, for many, the definitive failed experiment of the type. The result of this was that attention turned to monetary policy after 2000.

This too has been a failure, as described in books such as Bank of England governor Mervyn King’s The End of Alchemy (2016) and Federal Reserve staffer Danielle DeMartino Booth’s Fed Up (2017). Central bankers themselves were saying: “This doesn’t work, so please stop asking us to make everything better with monetary and financial manipulation alone.” Central banks that have gone down the negative-interest-rate path, with nothing much good to show for it, may now attempt to return to “normalcy.” In December 2019, Sweden’s central bank was the first, of those that attempted “negative rates,” to end that experiment after five years.

Sweden’s central bank recently ended its “negative interest rate” policy.

Naturally, attention is turning back toward … government spending. There is always a cohort in the government that would love to spend more money, and a choir of economists can always be rounded up to tell everyone how wonderful it will be. But, the true believers are scarce these days. Most people know the scam by now.

One group is going toward “modern monetary theory,” which uses extreme levels of monetary manipulation (basically straight-up printing press finance) to fund extreme levels of useless government spending. It is doubling, tripling and quadrupling down on the same old Keynesian playbook that has served up little more than disappointment over the past ninety years. Another group is probably watching this spectacle and saying: “we need to find another solution.”

The important thing to understand is that Keynesianism, of the monetary or fiscal sort, is all about macroeconomic distortion. For the Classical economists, monetary and financial distortion was bad: it created all sorts of artificial incentives and pressures on the economy that were ultimately unproductive and wasteful. The Classical ideal was money that was stable, predictable, neutral, unchanging and free of human influence. In practice, this was the gold standard. Interest rates were left to the free market. For nearly two centuries, until 1971, it helped make the United States the wealthiest country in the history of the world. On the spending side, the Classical view was that wasteful spending was a waste. You took productive resources from the economy (labor and resources, via either taxes or debt finance), and squandered them to create nothing of value. This is economic destruction. It took ninety years, but I think we have established by now that Two Wrongs (the monetary and fiscal distortion of Keynesianism) Don’t Make A Right.

In the near future, we may have a cyclical recession, or we may have a persistent condition of stagnation and mediocre growth. Unfortunately, the Classically-leaning economists today, as in the past, too often say: “Do Nothing.” They mean by this: don’t mess with the currency and don’t spend money on waste. Good idea.

But, governments can certainly do something. This is all the things — many, many, many things — that produce fundamental improvements in the economy. It is not creating distortions, and blockages, but removing them. It might mean reducing regulatory burdens, or stabilizing currency values, or allowing interest rates to reflect real market forces so that capital is allocated correctly. It should certainly include tax reforms that encourage more economic activity while also raising the necessary revenue. It should include reducing wasteful spending, not increasing it. It might include a balanced budget. It might include solutions to many of our pressing problems today, such as chronic housing shortages in cities with job growth, or fixing our disastrous healthcare system, or (at the municipal and State level) improving rail transit systems to reduce automobile dependency.

With such a long list of beneficial things to do, “Do Nothing” is totally unacceptable. In the Post-Keynesian Age, we do not mess up the economy with macroeconomic distortion, either of the monetary or fiscal sort. Nor do we “Do Nothing.” Whether in response to long-term stagnation, or short-term recession, get out this long list of Things To Do and get to work.

Watch what people talk about. The Keynesian playbook (and the “Do Nothing” response) has become such a habit that a lot of people in government seem incapable of any other action. When this happens, kick sand in their face and tell them to get lost.