(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on December 20, 2021.)

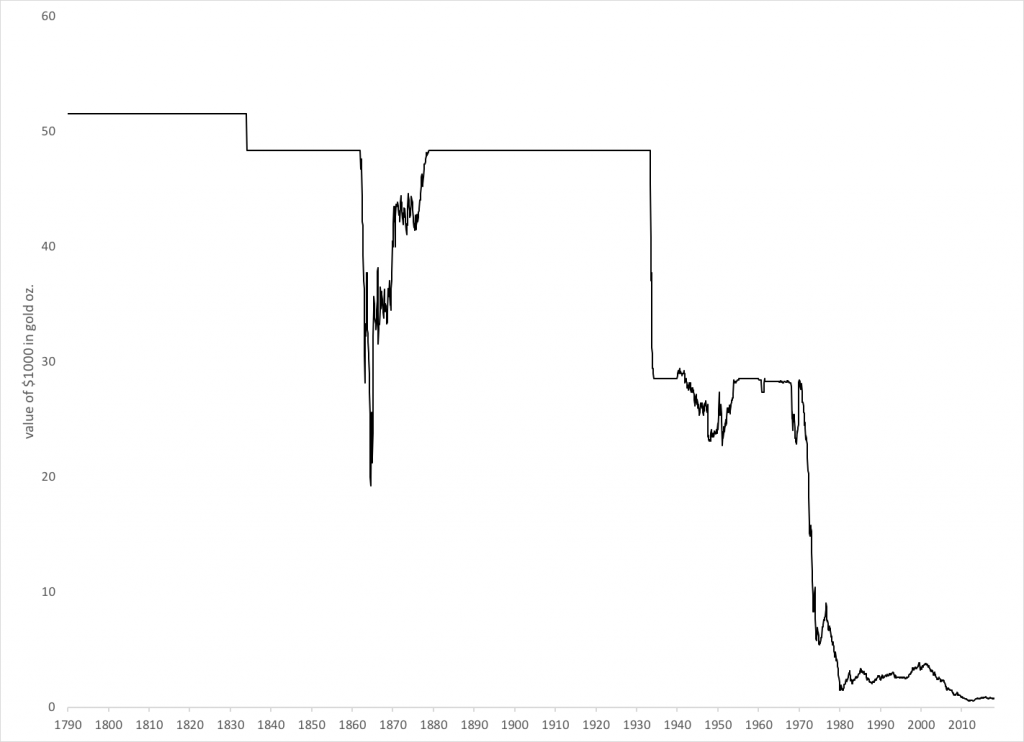

The historical record is clear: countries that have currencies based on gold tend to do very well. Those that don’t, usually run into difficulties. The United States had a dollar based on gold (with some lapses) from 1789 to 1971, and became the wealthiest and most successful country in the world. Soon after the US gold standard era ended on August 15, 1971, someone asked the 31-year-old economist Arthur Laffer what he thought the outcome would be. “It won’t be as much fun to be an American anymore,” he reportedly said. Some people today still ask: “WTF happened in 1971?” Laffer had it all figured out.

If you want to understand why things work out this way — why Arthur Laffer could make a prediction like that, and be right — you have to understand the principle of Stable Money. It’s very simple: money is best when it is stable in value. It doesn’t go up or down in value, as might be expressed in the foreign exchange market. Today, Turkey’s currency, the lira, has been falling in value, and we generally look at this as a bad thing. Why is that? But, we don’t want currencies to go up in value either. That would make debts harder and harder to repay, until eventually there was a wave of defaults. No fun.

On a more subtle note, a stable currency is like a measuring-rod that doesn’t change length. A stable “measuring rod of value” allows us to interact in the market economy effectively. The “information” contained in prices, which guide all aspects of the monetary economy, is not corrupted by changes in the currency itself. This idea was expertly elucidated by George Gilder in The Scandal of Money (2016).

Or, as Arthur Laffer later said: “Monetary policy’s specific purpose should be to provide a stable valued currency both now and far into the future.”

The early economist David Ricardo said nearly the same thing in 1816: “A currency, to be perfect, should be absolutely invariable in value.”

That is why most countries today have a simple stable-value policy. Usually, they link their currencies to the dollar or euro, either tightly or loosely. Sometimes, we may lament that they do not execute this policy with as much skill as we would like. But, that is nevertheless the basic idea. They learned that the effects of unstable money (like Turkey today) are bad enough that they should be avoided.

Probably, you rarely hear any discussion about “stable value” as some kind of ideal, even though most countries in the world are doing it right now. The major central banks do not seem to hold this ideal at all. They aren’t even trying to achieve stable value. Not surprisingly, they don’t achieve it. This has consequences.

We live in an era of “floating fiat currencies.” These currencies’ values are supposed to go up and down, by design. Central banks never talk about fixing this problem. Instead, they talk about something else: manipulating the macroeconomy, through some kind of currency and interest rate distortion. This they talk about incessantly.

The whole idea of a currency of stable value is that it is “neutral:” It does not distort commerce, like a meter or kilogram that doesn’t change length or weight. The whole idea of a floating fiat currency is that it does distort commerce.

All those countries that link their currencies to the dollar or euro are effectively giving up “floating fiat currencies.” Their currencies don’t float, they are fixed in value, to an external benchmark of value, the dollar or euro. Thus, they are depoliticized.

A gold standard is the same idea. Currencies’ values are linked to gold, an external standard of value. We do not assume that gold is a perfectly unchanging measure of this ideal of “stable value.” But, after centuries (actually millennia) of experience in these matters, we have determined two things.

1) It is good enough. Whatever variation gold may have, against this ideal of Stable Value, has not been large enough to matter very much. It works very well.

2) There is no better alternative. Nobody has found some measure of “stable value” that is superior to gold.

Gold also has what we might call political advantages. Let’s say that a bunch of eggheads at the Federal Reserve came up with some statistical concoction that they claim is even more stable in value than gold. This has never happened, in part because they don’t even try. Let’s make-believe that it is not impossible — although it looks impossible — but actually happened. Then what?

This statistical concoction, no matter how wonderful it was, would immediately be subject to political pressures. One way or another, there would be attempts to somehow adjust the outcome to affect the macroeconomy — before an election, for example. If you look at the continuous stream of revisions of the Consumer Price Index that have taken place, it is hard to imagine any statistical concoction that wouldn’t be subject to a similar continuous process of revision, to serve a continual series of agendas.

Second, other countries would be hesitant to adopt this. They would be, in effect, declaring a sort of political allegiance, which could be risky, as we have seen in the eurozone. Gold is the one standard that everyone has been able to agree on, in the past, because it is not the property of any one government.

It is easy to see why today’s most popular cryptocurrencies can’t serve as a measure of Stable Value. Their values are not stable at all, but fluctuate wildly. However, you could certainly include today’s crypto innovations into your gold standard system. Already, some “stablecoin” cryptocurrencies have been developed, that are linked to gold, including Tether Gold, Kinesis Gold and Coro.

“Money” is a tool, like a hammer. We make hammers out of steel, because a steel hammer best approaches what we want a hammer to be — that is, hard and heavy. We made money out of gold, because gold best approaches what we want money to be — stable in value. You can see this, because we assume that money is stable in value, even when we know that it is not. For example, when the price of oil goes from $70 to $80, we assume that the value of oil went up 14%, as measured in a money of stable value. We do not assume that the value of the currency fell 13%, while oil remained stable, although that might be what actually happened. This is called the “Money Illusion.” It’s actually one thing that makes macroeconomic manipulation via floating currencies effective. People assume that their money is stable in value, although actually they are floating fiat currencies. This is how central bankers fool people to do things — invest, borrow, spend, hire — that they would not do, if the currency was stable in value.

When you come to understand that money should be stable in value, free from human intervention, and you realize that linking the value of money to gold has always been the best way to achieve this goal, then there is no other conclusion but a gold standard system.