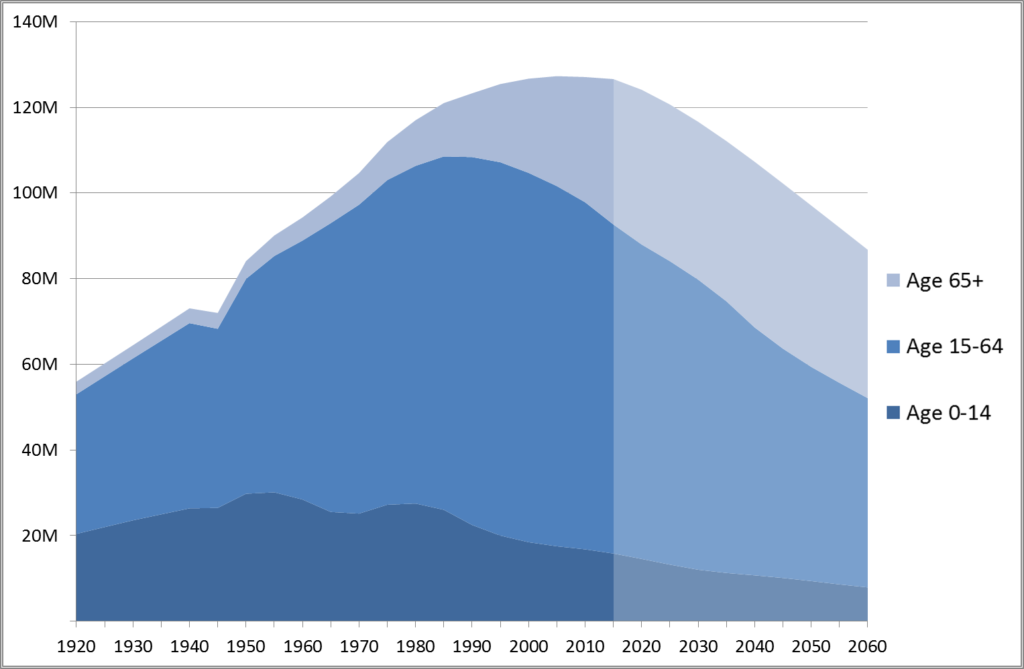

I have been arguing that a decline in population (“demographic collapse”) need not be a bad thing. If per-worker productivity remains high, or better yet rises considerably, then individuals and the society in general will remain wealthy and prosperous. The main issue, as I see it, is not the total population, but the increasing skew toward seniors that results when birthrates are low. Seniors have already become a very high percentage of the population, compared to historical precedent, due to increased lifespans. We will have to adjust our social institutions and expectations in a way that is compatible with this fact. Here is how it looks in Japan, which is something of a forerunner in these issues.

By the way, the difference between the fertility rate in Japan (1.36 children per woman) and the United States (1.70) is entirely attributable to the high rate of births to unmarried women in the US (40%) compared to Japan (3%). The fertility rate of married women is about the same. This might be more of a good thing than a bad thing. Although it means that Japan’s population would shrink more rapidly, it also means that 97% of the children would be born to married households, avoiding all the pathologies of children raised to single moms.

I have argued that a rational response to declining birth rates is:

- A focus on increasing productivity per worker, especially as the ratio of unproductive adults (seniors) to working adults rises. This basically means good economic policy, which is: Stable Money and Low Taxes.

- Moves toward reducing the economic costs of seniors, which probably means shared households, either seniors moving in with their grown children, or seniors banding together into large senior households or institutions. It probably means reducing government-funded healthcare expenses for seniors with little useful lifetime remaining.

- Moves toward increasing the productivity of seniors, either in the informal economy (childcare for grandchildren, household tasks), or in the formal. Although senior workloads may be reduced substantially, the idea of “retirement,” or a 100% switch from production/work to consumption/leisure, may be abandoned. Actually, even very wealthy people today rarely retire to straight leisure, but remain active managing their wealth or staying involved in their field of specialty. How much free time does Warren Buffet have?

Instead, governments are likely to take a completely different approach. Many institutions today are basically designed for growing populations and a relatively low ratio of seniors/population, the conditions of the middle twentieth century when these institutions and patterns were established. It has been said that pay-as-you-go State pension systems, such as Social Security, are similar to Ponzi Schemes. Indeed, like a Ponzi Scheme, payouts to “early investors” (seniors) are made from the inflows from “late investors” (working-age people). In a real Ponzi Scheme, the game works when the number of people coming in is greater than the number going out. It requires “population growth.” Today’s pay-as-you-go schemes have a similar character. To keep population growing, governments have turned to open immigration. This is problematic on many levels. But, also, it is unnecessary. I would oppose the idea that open immigration is necessary due to demographic issues.

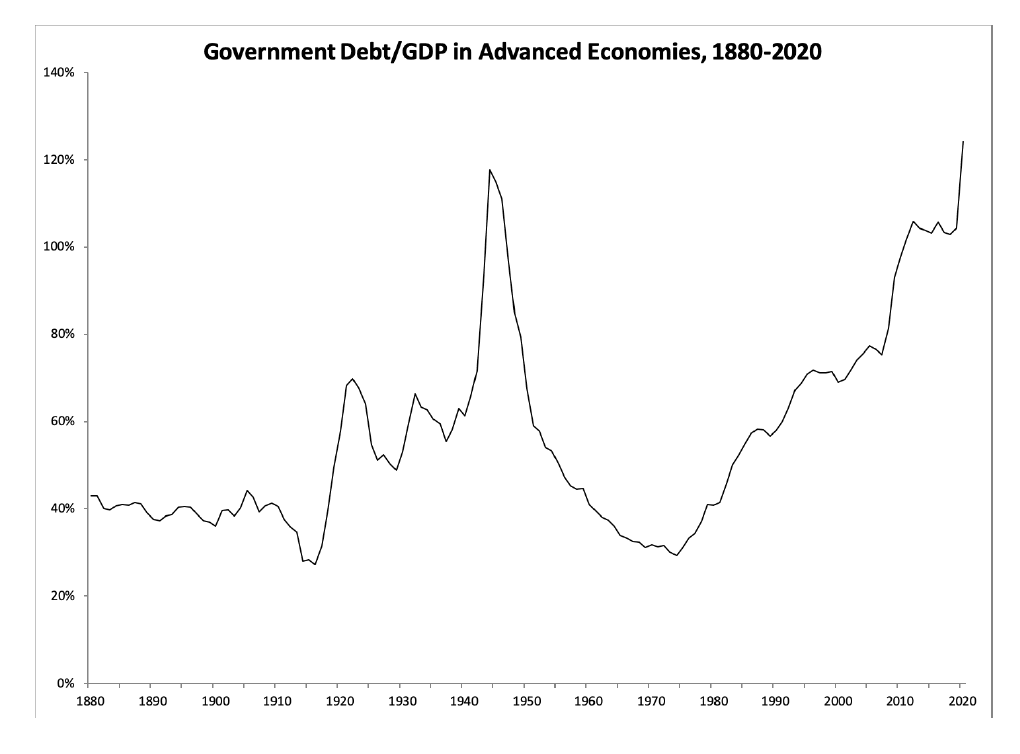

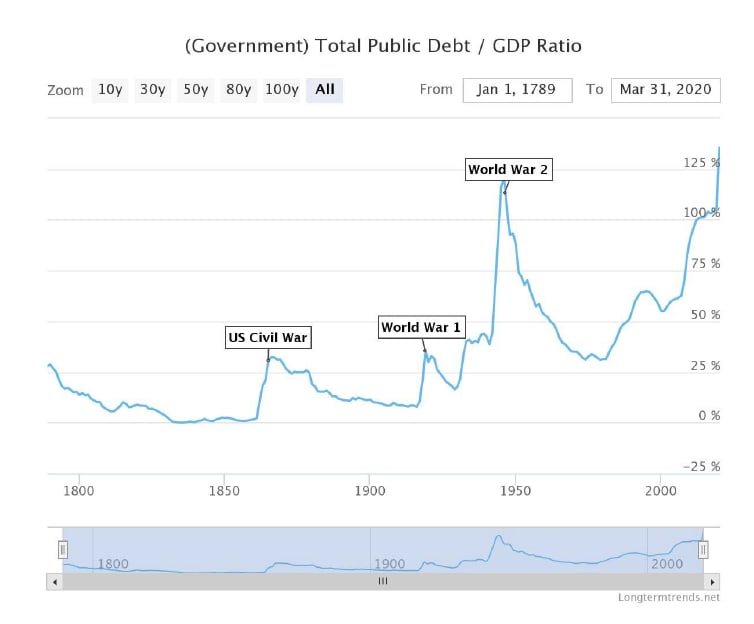

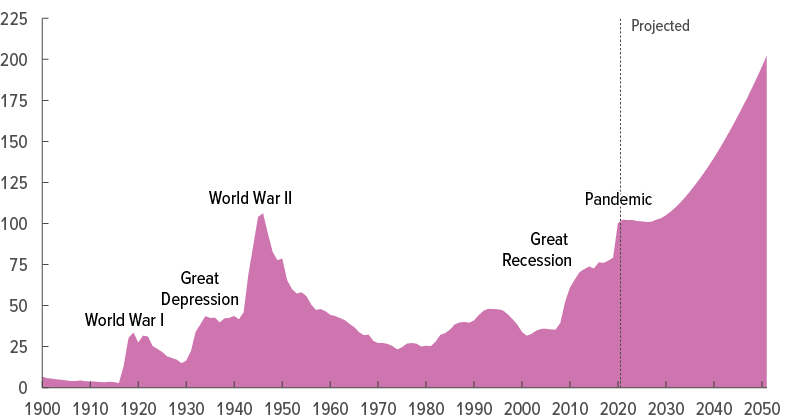

Another, similar sort of Ponzi is the pattern of rising debt levels. In the past, countries ran up debt during major wars, and during peacetime, budgets would be mostly balanced. Since nominal GDP tends to rise in peacetime, this would bring down the debt/GDP ratio, making the wartime debt less burdensome.

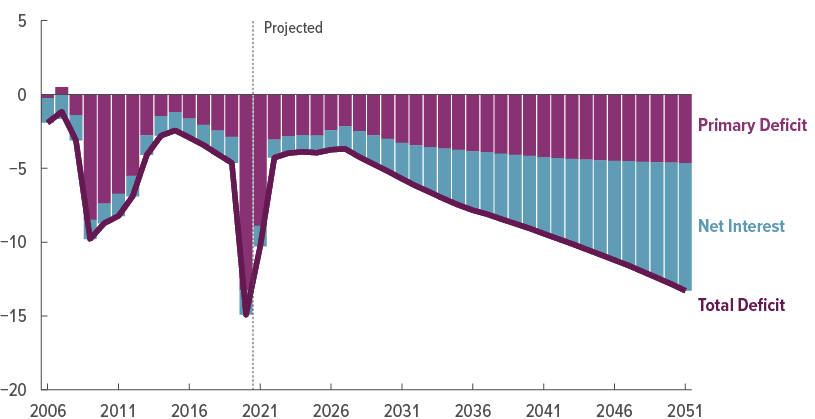

Unfortunately, since about 1970, governments have gotten themselves into a pattern of chronic deficits and rising debt/GDP levels even in peacetime. This creates the issue of “debt dynamics.”

Let’s say that, in a given year, the debt increased by 4%, and GDP increased by 4%. The debt/GDP ratio would remain stable. However, if the debt increased by 4%, and GDP increased by 2%, then the debt/GDP ratio would climb, debt service costs would climb leading to even larger deficits, and finally there would be a debt crisis. Now, we have seen that, assuming that productivity per worker was unchanged in either example, a working-age population growing at 1% per year would have about 2% higher GDP growth than a working-age population shrinking by about 1%. Again there is a sort of Ponzi Dynamic where a growing population of suckers is needed to keep the scam working.

The solution, of course, is to go back to the old pattern of balanced budgets during peacetime. The problem isn’t a shrinking population — we already established that per-worker productivity and income is unchanged in either example — it is the pattern of chronic deficits and the Ponzi Dynamics that results. However, the other issue here is that a shrinking population also implies a growing ratio of seniors/population. These seniors will tend to push budgets into deficits, because government spending today is very highly skewed toward payouts to seniors, in the form of State Pensions (Social Security) and State Healthcare (Medicare or any State-funded system). Thus, the factors that create deficits in the first place will tend to create bigger deficits. So, you get a Double Ponzi — income to the Ponzi declines while payouts grow.

But, it is worse than that. As the Senior population ratio increases, Seniors become more politically influential. In democratic systems, they will tend to push the political system toward protecting their payouts, and then, increasing them. Now we have three factors: Debt Dynamics, Spending Dynamics of existing policy, and Policy Dynamics which tend to make the other two factors unfixable, and maybe make them worse.

The United States was based on principles which would have prevented this outcome. The idea was that the Federal Government would be excluded from all domestic social-welfare-type spending. This was a matter for the States. The Federal Government had Enumerated Powers, which basically amounted to: Foreign policy and the military. And, this was indeed how it was mostly done, for most of US history. That explains why we had a pattern of debt during wartime, and balanced budgets during peacetime. Social Security was introduced in 1936, but the big rise of the Welfare State at the Federal level didn’t happen until the Great Society push of the 1960s.

At some point, we might want to solve all these problems by going back to the original Constitutional principle of restricting the Federal Government’s spending to, basically, foreign policy and the military. This would, obviously, make it a lot easier to balance the budget.

Domestic policy would be returned to the State level. You could argue that this simply moves it around. You would have the same problems at the State level. But, since States would be creating new institutions from scratch, they could make them appropriate for today’s conditions, rather than continuing legacy programs that have gone rotten. For example, each State would be able to establish its own healthcare system, independent of other States. That might get interesting. Second, we establish competition between States. This would favor those States with successful responses to the situation.

One of my points is: Good Economic Policy. Obviously, if we want to support a growing ratio of Seniors, and also make the payments on government debt, and also have ample tax revenue so the government budgets don’t go into deficits, we want a healthy economy with high and rising incomes for workers. It is not that hard to find a way to increase worker productivity by about 1% per year, which would also mean higher incomes per worker. That might be pretty nice. Low Taxes and Stable Money.

Unfortunately, another predictable response by governments is basically “austerity.” They will want more revenue, to cover the rising expenses of their bloated legacy programs including public pensions, healthcare, and the growing debt burden, and also, to help reduce the deficits that are pushing the government toward a debt crisis.

This will tend toward Higher Taxes. Which, may I note, is the opposite of Low Taxes. Get it? (I have to make it simple because most politicians, and their teams expert economic advisors, won’t get it.) It is very common to find, in government arguments along the lines of: “Well, we agree that Low Taxes would be good, but we really need the money, so we really need to raise taxes.” But, what you find, in real life, is that governments that reduce taxes, and enjoy economic growth as a result, are often those that are up against the wall. They figure out: “things are not going to get any better unless we reduce taxes.” Then they do it, and wonderful things happen. This was the pattern throughout Eastern Europe, which adopted Flat Taxes during the late 1990s and 2000s in the middle of destitution and crisis. You never find a country that says: “Things are so wonderful now, and finally we have more tax revenue than we know what to do with, so finally we can reduce taxes.” That never happens, except as the result of major prior tax reductions.

The outcome of higher taxes, or “austerity,” would be depressed economic productivity, which would mean less tax revenue, a depressed GDP, more government spending, bigger deficits, a rising debt/GDP ratio both because of rising debt and depressed GDP (growing less than would be the case with better economic policy), and, of course, an endgame of Sovereign Default, of one flavor or another.

Over time — not very much time — the best way to get more tax revenue is to have a growing economy. This arises from good economic policy, including Low Taxes. If you had better economic policy (including lower taxes) leading to a 1% improvement in growth, that adds up to a lot over time as growth compounds. If you had a negative 1% effect from “austerity,” that would add up to a 2% combined difference between rather modest growth-supportive policies, compared to rather modest growth-depressive policies.

Along the way, governments will likely figure out that they “don’t need to find the money,” (to use MMT advocate Stephanie Kelton’s term), but can just print it. Things have already gone pretty far down this road throughout the developed world. This might lead to a pattern of “financial repression,” most likely in the form of a steady but not catastrophic decline in currency value; or, perhaps, a hyperinflationary blowout when the government really, really needs to make the payments, and there doesn’t seem to be any alternative but to just print the money, consequences be damned.

This is, obviously, not the same as Stable Money. So, we would have both Rising Taxes and Unstable Money. This would burn the whole thing to the ground in not much time, and then we would be free to fix things more-or-less along the lines of the principles I outlined at the beginning. I would say that things today have a strong tendency in this direction.