Today, we will look at Savings and Investment in the United States, which is directly reflected in the Balance of Payments.

You can think of the Balance of Payments as the difference of Exports of Goods and Services, and Imports of Goods and Services, with the difference balanced (trade is always balanced) by the financial account.

Or, you can think of the Balance of Payments as the difference of Acquisition of Foreign Assets by US entities, and the Acquisition of US Assets, by foreign entities. (A loan here is the “acquisition” of a debt asset.) The balance is made up by Goods and Services account, or Current Account (which also includes overseas income).

Both of these views are fundamentally correct. When you decide to buy something, you also decide not to save the money you are spending; and when you decide to save and invest, you are also deciding not to spend the money on consumption. At the aggregate level, a combination of billions of such decisions among millions of individual entities, you have the aggregate Balance of Payments.

When you think of it this way, it is easy to see that, if the US savings rate was high, then there would be a tendency to purchase overseas assets (because you have to acquire something, that is the definition of financial savings), and also, a tendency to purchase domestic assets, which means less of them would be purchased by foreigners. The result is a Current Account Surplus.

When looking at domestic Savings, there are some big factors that we should consider.

The basic idea of Savings, especially financial savings, from an economic perspective is that it is the flip side of investment, which means the creation of some new productive capacity. If we do not spend this money, but basically buy stocks and bonds or some other productive asset like real estate, we are basically financing the creation of new productive assets. This creates jobs, and creates economic growth. Wonderful!

But, there are two main ways in which this happy conclusion is bypassed. The first is government debt. With a few exceptions, in practice a very minor part of overall spending, government spending is consumption. There is nothing of lasting value created. This includes even things that are seemingly long-term productive assets, like a bridge or a National Park. Yes, a bridge is useful, but when the government spends five times as much on a bridge as an engineering and construction firm would contract to do it in the private market, is that really “investment”? Maybe about 20% of it is; and the other 80% is “consumption”.

When the government issues net debt (runs a deficit), basically the government is taking financial savings, which could go to creating new productive assets and creating jobs, and instead consuming it. It is “negative savings.” This is very bad. The result is that the Current Account Deficit tends to be very large. The reason for this is that all the proper real investments have to be funded, from domestic capital and foreign capital, and then, on top of that, the government deficit has to be funded. Since we already used all the domestic savings to fund the real investments, we then have to fund this government deficit, with the difference made up either with foreign capital, or excluding some domestic investments, which means fewer jobs and less growth.

The other main way in which savings does not find its happy result in new productive enterprises, but is rather consumed, is consumer debt. This is a bit of a grey area, since some consumer borrowing is something like “productive investment.” This might be true of a home loan, or an auto loan, or a student loan. But, also, some home lending, and auto lending, and student lending, can also be called “consumption” since it amounts to consumption rather than an increase in productive capacity. To this we can add a wide range of lending that is plainly for consumption, such as lending for vacations, or credit card lending.

This consumer debt is generally netted out against consumer savings in Net Consumer Savings. We see only the Net Consumer Savings Rate. However, it is easy to see, that if there is less consumptive lending among consumers, then there will also be less consumer lending as a whole, and thus Net Consumer Savings would rise.

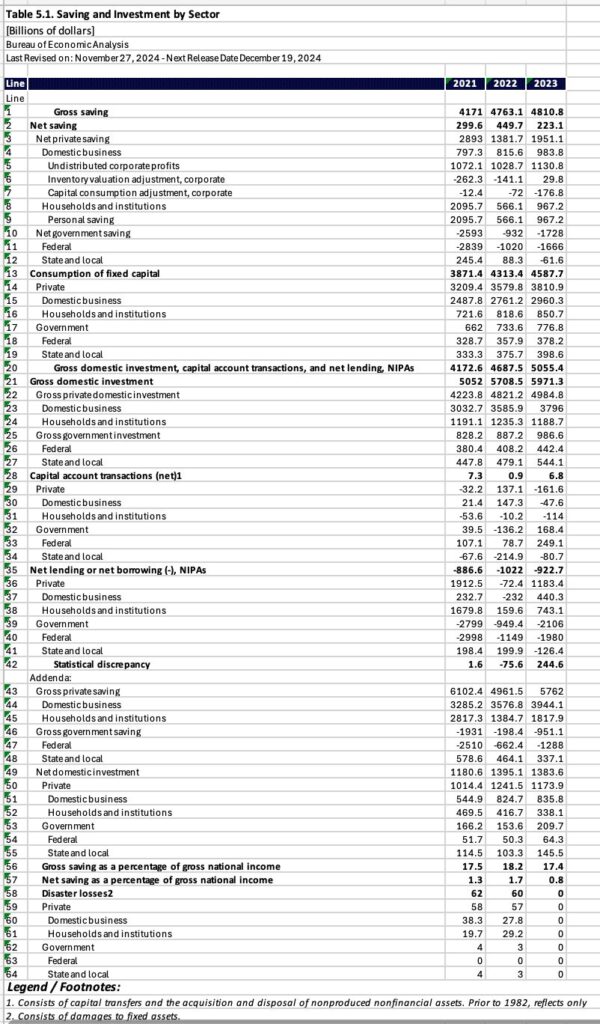

Here’s what recent Saving and Investment in the US looks like:

We see that Net Private Saving was $1951 billion in 2023, all money that could be used to create new productive enterprises, aka “creating jobs,” that will lead to future productivity and prosperity. But, Net Government Saving (the deficit) was -$1,728 billion, consuming nearly all of the combined total of personal saving and corporate profits, leaving Net Saving of a paltry $233 billion. Gross Domestic Investment was $5,971 billion, which seems like a big number, but most of that just offsets Depreciation (consumption of fixed capital), which was calculated at $4,587 billion. Nevertheless, that’s about $1,400 billion of Net Investment, which obviously exceeds Net Domestic Savings of $233 billion. That difference was funded by foreigners, and turns up as a Current Account Deficit. We can also see that if the government didn’t disappear $1,728 billion of capital, then all of the Net Investment would be funded, leaving some money left over which could be invested overseas, as a Current Account Surplus. Or, with all that capital looking for a home, there could be more domestic investment, which means more jobs and more growth.

All job creation comes about from investment. As a general rule, over time, it takes fewer and fewer people to produce the same amount of goods and services. This is good — it is the same as increasing productivity. But, increasing productivity means fewer and fewer jobs, unless someone creates some new jobs, which basically means creating new goods and services, since the existing goods and services can be created with fewer and fewer people.

We tend to think of “entrepreneurialism” in terms of new enterprises that might grow very big. Venture Capital-type stuff. However, most “investment” is basically just doing the same thing, but more of it. Starbucks going from 1000 outlets to 2000 outlets probably doesn’t seem very “entrepreneurial.” Maybe this was internally financed, from cashflow, and thus no equity or debt was issued. (Statistically, that would be reinvestment of corporate profits.) But, each new outlet represents a new investment, and there is no guarantee of success. Also, each new outlet requires more employees. Starbucks going from 1000 to 2000 outlets creates as many new jobs as all of Starbucks’ previous history, going from 1 to 1000 outlets, combined.

Talking about Starbucks going from 1000 to 2000 outlets sounds rather dry and boring, but it is perhaps easier to see that this is indeed very entrepreneurial when we look not a thousand new outlets, but just one. Let’s say that Starbucks — no, it is actually Jack Thompson, in charge of new business development in the Midwestern region; or perhaps Thompson is a franchisee, in fact a small independent businessman — makes a decision to build a new Starbucks outlet in a shopping center on the corner of Western Avenue and 144th Street, in Dubuque, Iowa. Thompson’s team calculates the potential market available, competitors, local incomes and propensity to buy expensive sugary coffee, the cost of construction, the attractiveness of building a new structure instead of leasing an existing storefront, local labor costs, local government and regulation, and all the other factors that go into opening a new retail outlet. You have to put up a chunk of cash — capital investment — upfront, to build the outlet. Maybe it is $300,000. Then you have to make that money back, at a dollar a cup, after expenses, just to break even. It’s a gamble.

Thus, in terms of Economic Nationalism, a big Current Account Deficit might reflect some underlying problem. In our case, it reflects the fact that domestic capital creation (the savings rate) is rather low; and even this small sum of capital is mostly obliterated by the government deficit. Thus, to have much of any net investment at all, we have to raise capital from overseas, which produces a Current Account Deficit. The solution is a much higher savings rate domestically, and much less capital destruction by government borrowing. Then we would be able to finance a lot more domestic investment, in the process creating jobs, and also, have something left over, which becomes net foreign investment, which is the same thing as a Current Account Surplus.

At other times, a Current Account Deficit can be a sign of good health. A certain locale is so attractive for business that, even with a high rate of domestic capital creation (savings rate), and no significant government deficit, all the available local capital is put to good use; and there are still so many business opportunities available that foreign capital also gets involved, producing a Current Account Deficit. This was the case for the United States during the 19th century, and also, South Korea during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Regrettably, this happy condition is rare today.