Unfortunately, legitimate issues regarding foreign trade often become mixed up with talk about the “current account deficit,” which is mostly fallacious and erroneous, and which has served as a do-anything catchall over the decades (actually centuries) for whatever it is that you want to do.

Trade is always balanced. There is no “trade imbalance.” Never has been, never will be. “Unbalanced trade” is a gift — which is also perfectly fine, and bigger than you might think, in the form of official foreign aid and also overseas remittances. But these gifts too are “balanced” in the sense that there is no particular problem with it, or some residual issue that needs to be resolved in the future.

However, as is the case with many economic statistics, the Balance of Payments may reflect some other problem. This other problem’s effects show up in the Balance of Payments.

To understand what the Balance of Payments actually is, let’s imagine an individual. This individual (or family) is engaged in “trade” with the “rest of the world,” i.e, the economy. We will imagine that this individual primarily “exports” employment labor, for which they are paid. Then, the individual “imports” whatever they spend their money on, at Walmart or Amazon for example. Even in this case, there is quite a bit of a “domestic economy,” or productive activity within the household. This might include making dinner, raking leaves and cleaning the toilet. So, there is both “domestic” and “foreign” trade in our example.

Let’s say that this individual runs a “current account surplus.” They receive money from their employer, but they do not spend all of it on current consumption. There is something left over. This is “savings.” This “savings,” from the start, takes the form of some kind of financial asset. It might be paper banknotes, or a bank account balance. In the past, it might have been gold or silver coins, which are really a sort of manufactured item and could be classified in the same category as other manufactured items, like copper and lead. But, that is of course rare today.

This “savings” might be traded for some other kind of financial asset, such as stocks or bonds. It might take the form of a real asset, like investment real estate. Thus we see that the “trade “with the rest of the world is balanced. The individual ran a “current account surplus” with the Rest of the World, producing an acquisition of a financial asset (savings). The Rest of the World ran a “current account deficit” from the individual, basically borrowing money or selling assets (stocks or bonds or bank accounts). In the end, the Balance of Payments balances, because it always balances, like a corporate balance sheet.

But, sometimes an individual runs a “current account deficit.” They spend more money than they receive. This is only possible if they borrow money or sell assets to the Rest of the World. For example, a person might buy a house, and borrow the money in the form of a mortgage. The RoW sells that person a house, and the person “sells” a financial asset (30 year mortgage) to the RoW. For that year, that person had a huge “current account deficit.”

But, maybe buying a house was a good thing. So, running a “current account deficit” with the RoW is not necessarily good or bad, in itself. In this case, it might be a “productive investment.” At the national level, mostly corporations might borrow money, for all kinds of good purposes. They make use of foreign capital to develop the domestic economy. The money is paid back, and then there is also a productive asset that continues to provide benefits.

But, maybe it was a bad idea. Maybe they bought more house than they really should have. Maybe they didn’t buy a house, but borrowed money to go on a fancy vacation, and instead of a productive investment, the money disappears in consumption. Maybe their borrowing is a sign of financial ill-health or bad decisions.

In this case, we can see that the financial ill-health of the individual shows up in the Balance of Payments as a Current Account Deficit (borrowing money), but the Current Account Deficit itself is not the problem. It is just a record of the fact that money was borrowed.

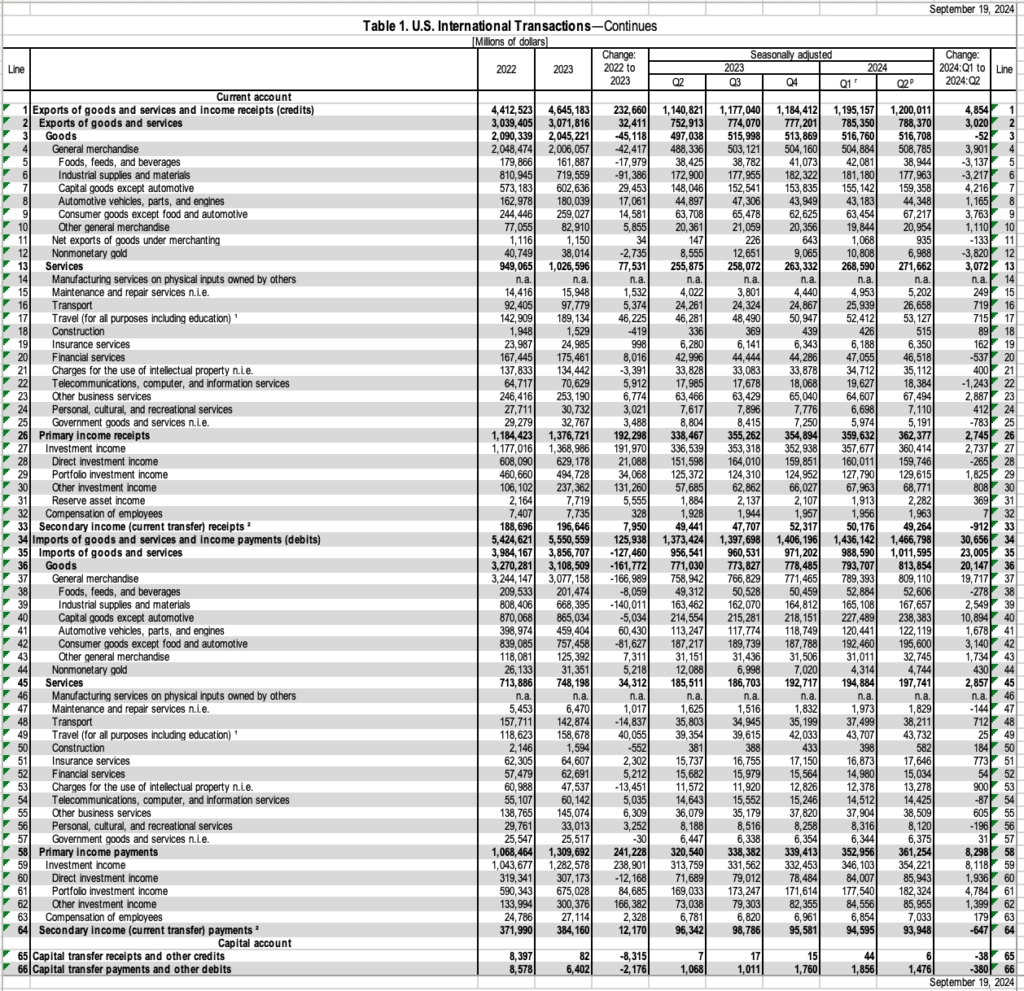

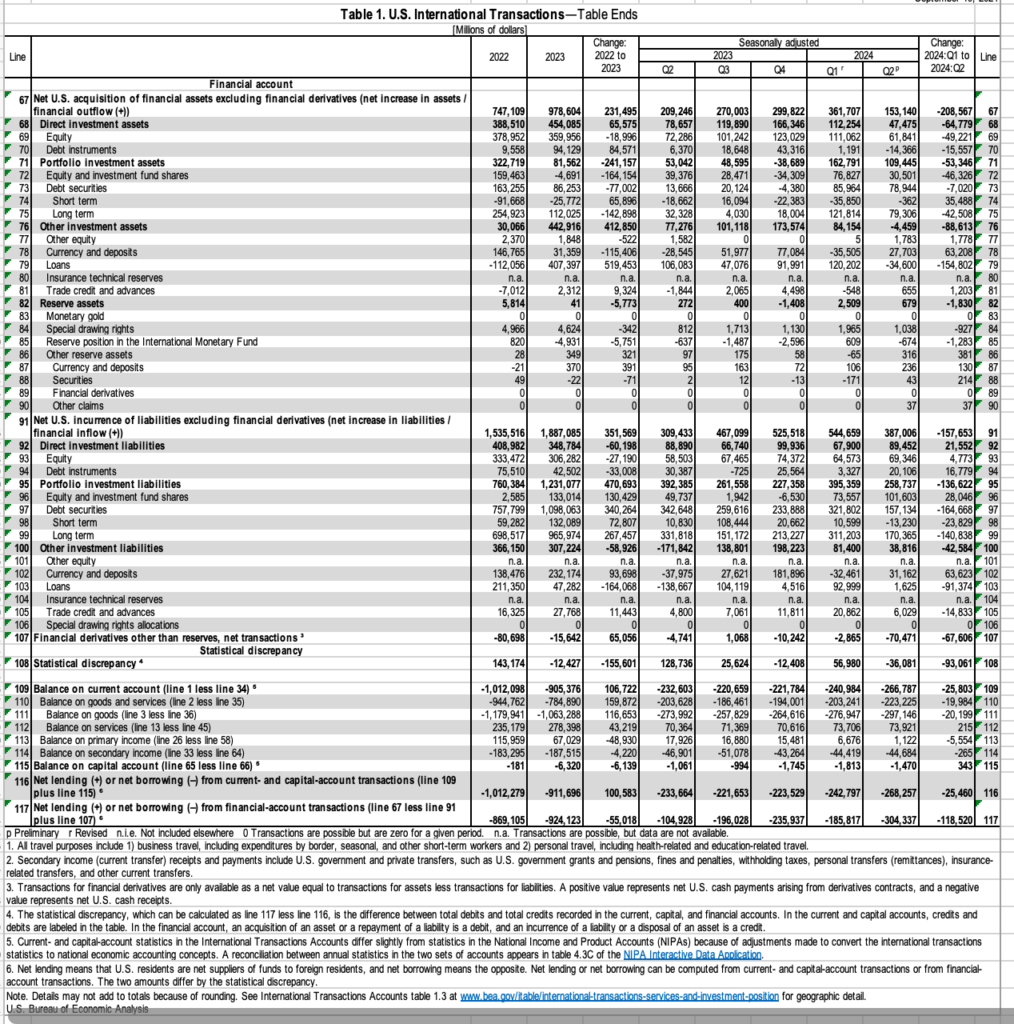

Now let’s look at the real Balance of Payments:

We see that in 2023 there were $4.6 trillion of Exports, and $5.5 trillion of Imports. This had to be financed, which we see in the Capital Accounts where there was $987 billion of gross acquisition of investment assets, against $1,887 billion of gross sale (issuance) of investment liabilities.

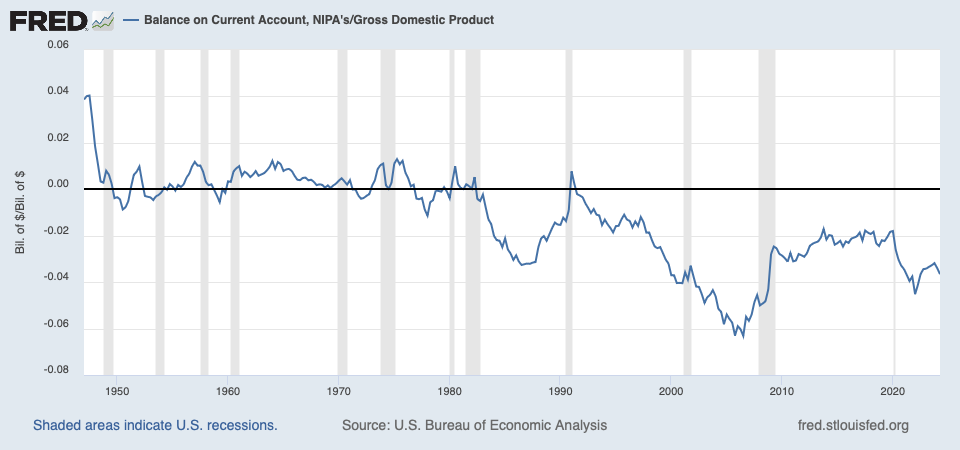

A summary of this is here:

The Current Account as a percentage of GDP looks like this:

It is about 3.5%, which is not actually so bad, although it does illustrate certain ill-health of the US government and economy as a whole.

We will talk more about the Current Account and Balance of Payments soon.