(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on August 28, 2019.)

Anyone who has followed my work knows that I sometimes don’t have very nice things to say about Team Gold — the community of gold standard advocates dating back to about 1950 or so. As a result, I am a little unpopular among them. But, one of the reasons why I wrote three books about the gold standard is that there were no good resources from which to learn the foundational concepts of this longstanding institution. The knowledge was lost. Unfortunately, the nonsense that comes from Team Gold, regarding gold standard systems, is often as bad as the nonsense from Team Funny Money (floating fiat currency manipulators).

Things have gotten a lot better over the last ten years. Nevertheless, I think there is still progress to be made. Here are some confusing notions you might hear from Team Gold that, in my opinion, cause more harm than good:

1) You can just “revalue gold.”If there is a litmus test that divides Those That Get It and Those That Don’t, it is the notion that a return to a gold standard requires some kind of “revaluation” of gold, typically at a price five to twenty times higher than the prevailing price. It was popularized by Murray Rothbard in the 1960s, who really should have known better. But the whole point of using gold as a standard of value, the “monetary Polaris,” is that its value is reliably stable. You can’t “revalue it.” No government ever has. What you can do, however, is revalue a currency. For example, if the “gold price” is $1000/oz. one day, and then “revalued” at $5000/oz. some other day, the value of the dollar vs. gold has fallen by a factor of five. This is called a “devaluation of the dollar.” These arguments amount to nothing much more than unnecessary and destructive currency devaluations. Countries have gone from floating fiat to a gold standard many, many times — virtually the entire world did this during the 1920s, after the floating currencies of World War I — and this process has never taken place.

2) It’s all about the quantity of gold here or there. A gold standard system is all about value, not quantity. Gold, in a gold standard system, is a standard of value. The value of the currency is managed so that it is equivalent to a certain amount of gold. This is no different than currencies today that are linked to dollars or euros. The IMF tells us that more than half of all currencies today are “anchored” to some other international currency, so it is a familiar and functional policy. One way of accomplishing the gold “anchor” was to simply make the coins out of gold. This became rarer in the nineteenth century, as banknotes displaced coinage. In the 1950s, the dollar was reliably maintained at its $35/oz. gold parity, even though gold coinage was illegal in the U.S. All were gold standard systems, although perhaps flawed in some of their details.

Once we understand this, we can see that mining production is not very important, because it appears that changes in mining production don’t have much effect on the value of gold. One reason for this is that existing aboveground gold stocks — all the gold mined in past decades and centuries that is still with us — are about fifty times greater than annual production. Even the tenfold increase in mining production between 1830 and 1850 does not seem to have had any significant effect on the value of gold. Even if mining production did affect gold’s value, the significance is the change in value, not because some quantity of gold went here or there.

Similarly, we can see that it doesn’t matter if there is lots of gold here and little there, or if gold travels here or there, because it is the same value everywhere — the “Law of One Price.” If gold is the same value everywhere, then the value of currencies linked to gold are also the same. In general, we would expect to find that places that have a high demand for gold bullion — because of extensive use of gold coinage, or high reserve policies at central banks — would have a lot of gold (France in the 19th century), and places with a low demand for bullion, due to widespread use of banknotes and bank deposits instead of coinage, and lower reserve policies would have less gold (Britain in the 19th century). We might expect that, if demand for bullion increased or decreased, then bullion would flow from where it is in less demand to where it is in greater demand. This is true also for any other physical good, from copper to Chanel handbags. This is the process by which the Law of One Price achieves its equilibrium. It is the same process by which the number of dollar banknotes in Connecticut vs. New Jersey is determined. But, we don’t have to worry about it, because gold is the same value everywhere. Quantity statistics, whether stocks or flows, are not very important.

A lot of notions that are reflected in “price-specie flow” arguments dating back to the 18th century are really just confused representations of the Law of One Price. “Price-specie flow” notions, as they are generally depicted, are bunk; and economists have long been aware that there is no evidence of any such mechanism in the real world.

3) A gold standard “restricts” money supply. A gold standard does “restrict” the money supply in the sense that a government cannot “print money” willy-nilly in a fashion that would cause the value of the currency to fall below its gold parity. If the value of the currency falls below the gold parity, a properly functioning gold standard system would restrict supply to support the value. (This topic is discussed in a lot of detail in Gold: The Monetary Polaris). However, a gold standard system can expand to any degree necessary, to reflect rising demand for currency along with a growing economy. Between 1775 and 1900, the base money supply in the United States grew by about 160 times, reflecting the growth of the U.S. economy during that period. This was totally unrelated to mining production. The value of the dollar was essentially unchanged.

Besides government printing press finance, the other important way that a gold standard system “restricts” the money supply is that it disallows all sorts of “easy money” currency and financial manipulation policies. This is no different than a currency board today. Team Funny Money hates this — for them it is like sunlight on vampires — so they are always complaining about this “restriction.”

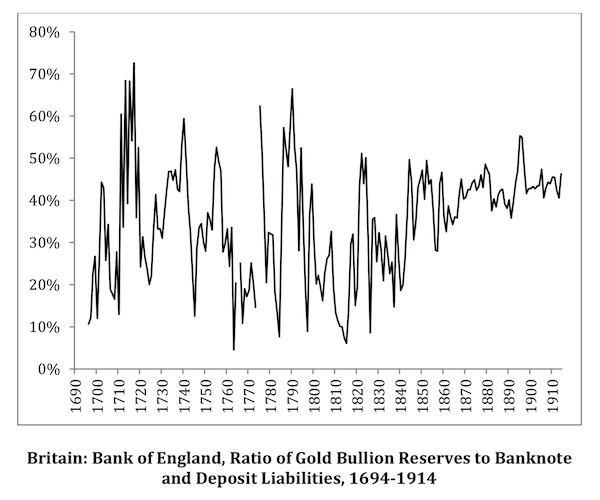

These aspects of “restriction” are good things. But, gold standard advocates sometimes think that the money supply in a gold standard system is “restricted” to the increase in world aboveground gold due to mining production (about 2% per year growth), or perhaps “restricted” to some stable unchanging amount. This has never been true. We actually have statistics on these things, for example the Bank of England’s balance sheet going back to 1696. It soon becomes clear that some people posing as “experts” haven’t the tiniest notion of what real-world gold standard systems look like, over a period of decades and centuries.

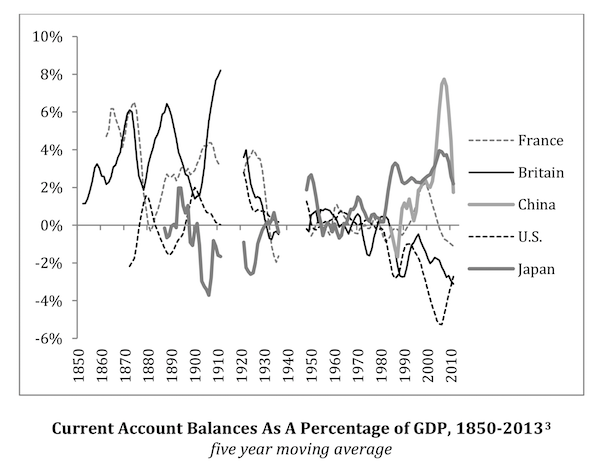

4) A gold standard has something to do with trade. A gold standard system is just a value anchor, little different than, for example, Hong Kong’s dollar-based currency board. You can import or export, or invest internationally, however you like and it really doesn’t have much to do with the currency. For a very long time, and especially during the 1950s and 1960s, there was an idea that a gold standard system was somehow wrapped up in the “balance of payments” or some such thing. People were very confused in those days. Actually, the Classical Gold Standard era of 1850-1914 was a time of free trade and open international investment. Some countries ran huge and persistent current account surpluses (Britain), while others ran current account deficits (the United States). International investing was very popular and the flows of capital were gigantic. You could say the same of Hong Kong today. It didn’t matter. Currencies were linked to gold, just as the Hong Kong dollar is linked to the U.S. dollar today.

5) There is not enough gold. The amount of aboveground gold today is about seven times greater than in 1910, due to mining production since that time. How can that not be enough? But remember that gold is really just a benchmark of value. You don’t need to store giant quantities of it in vaults, just as you don’t need to store millions of meter sticks in vaults to be able to use the meter as a measure of length. Just as you measure the length of an object against a meter, you can measure the value of the currency against gold (i.e., the number of currency units it takes to buy an ounce of gold). The important thing is that the value of the currency is maintained at its gold parity. This is accomplished by adjusting its supply: when the value is too low, supply is reduced, and when it is too high, supply is increased. All gold standard systems work this way, even 100% reserve or gold-coinage-only systems.

I think that it would be good for currency issuers (such as central banks) to have some kind of obligation to deliver bullion at the parity price. This is not really a technical necessity, but it imposes a sort of institutional discipline. It is similar to your local bank’s obligation to deliver $20 bills from an ATM on demand, which is “convertibility” of bank demand deposits. Do you think the bank holds a 100% reserve of $20 bills in its vault against your bank deposit? Bank cash reserve holdings are higher now after “Quantitative Easing,” but before the 2008 crisis, banks’ reserves of actual dollars was less than 1% of their demand obligations.

There is a notion that if a central bank offers gold convertibility, everyone will rush out and dump the currency and get the gold. But does this happen at commercial banks today? It does — there is a “bank run” — when the bank is not behaving itself. But normally, there is no problem.

In general, I suggest that central bank gold reserves should be about 20% of total aboveground gold. That is about the ratio that it is at today (if we dismiss reports that China or Russia hold much larger amounts). It is also the same ratio as in 1910.

Nobody wanted the Bretton Woods world gold standard system to blow up in 1971 — not even Richard Nixon, Federal Reserve Governor Arthur Burns, or any of the other major governments. Things were going very well in the 1960s. U.S. economic growth touched 5%; Germany was at 8%; Japan at 10%; even France and Italy managed 6%. One prominent member of Team Funny Money, comparing the prosperity of the Bretton Woods gold standard era to the mid-1990s, called the mid-1990s the “Age of Diminished Expectations.” Today, our expectations have fallen so much further that we now think the mid-1990s were some paradisical era. This is your economy on Funny Money. Yes, it can “give you a high.” They actually call it “monetary stimulus.” Most economists are addicted to it.

The Bretton Woods gold standard system blew up, in the midst of peace, prosperity, and earnest international cooperation, because people forgot how it worked. One reason that we haven’t gone back to that successful system (correcting some of the errors of the Bretton Woods era) is that, for a long time, people still didn’t really know how it worked. There were always an enlightened few, but the base of knowledge was not widely held enough. Team Gold was not ready for prime time. Team Funny Money is always going to misrepresent and demonize the gold standard system. Team Gold will beat them — historically, it has always beaten them — if it can get its story straight.