Gold is Stable in Value

April 10, 2011

The basic premise of a gold standard system is, first, that a currency that is stable in value is an important and desirable thing. Second, gold is stable in value. Thus, if you make the value of your currency the same as gold, then your currency will be stable in value.

That’s pretty much all there is to it, although it seems like even this kindergarten stuff isn’t well understood these days. A lot of people seem to think that the purpose of a gold standard is to make the quantity of money stable because it is hard to mine gold. Actually, gold standard systems in operation during the 19th century had rather dramatic changes in base money outstanding, which was no problem and just part of the normal operations of the mechanism that kept the value pegged to gold.

January 9, 2011: The “Money Supply” With a Gold Standard 2: 1880-1970

January 2, 2011: The “Money Supply” With a Gold Standard

January 23, 2011: The Gold Standard in Britain 1778-1844

January 30, 2011: Italy With the Gold Standard 1861-1914

Is the value of gold stable?

This is actually somewhat difficult to answer. I decided, after thinking about it for some time, that my answer will take three parts:

1) Price indications

2) Interest rate indications

3) Historical indications

The most important one is the third, historical indications. In many ways, the entirety of my book Gold: the Once and Future Money serves as a proof that gold is indeed stable in value. This is really the best and most complete sort of proof. However, it is also by far the most laborious. The idea is that, if you look at dozens and dozens of economic events over centuries of history, what you find is that when currencies change value compared to gold, then you tend to get corresponding inflationary and deflationary effects. In other words, it was the currency changing value, not gold. However, if a currency doesn’t change value compared to gold, then you don’t see much in the way of inflationary or deflationary effects. In other words, gold isn’t changing value.

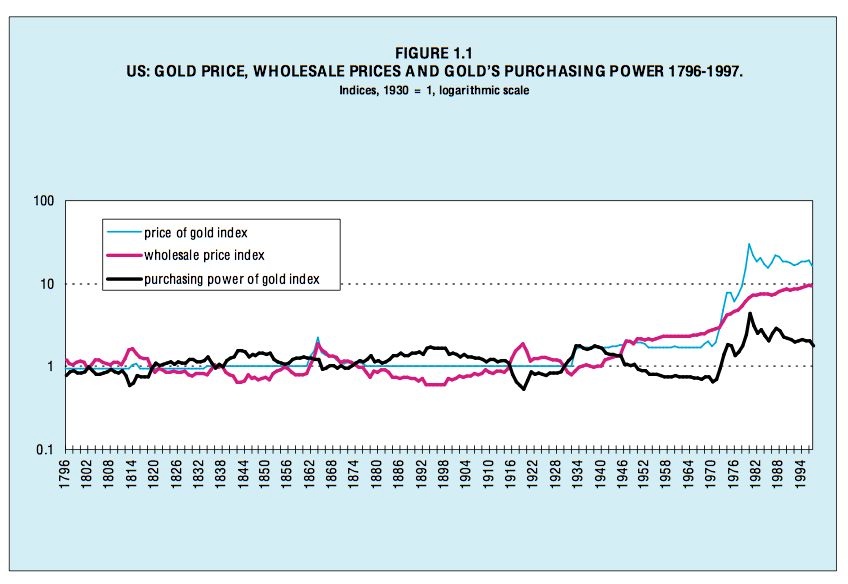

With that said, let’s start with the first, which is price indications. Unfortunately, when judging the stability of gold’s monetary value, we have a basic problem that there is nothing more stable than gold to which we can compare. If there was, we would use that thing as a measure of stable value, not gold. The only long-term price indications of note are commodity prices. Here’s a wonderful paper on that topic:

World Gold Council Research Study No. 32: Gold as a Store of Value

The point is, we have to know what we are looking at. We are looking at the prices of mostly agricultural commodities, in New York City. This is NOT NOT NOT comparable to today’s CPI, which is mostly stuff like owner’s implied rent, healthcare, and education costs. Second, we have to ask: why were Warren and Pearson doing a study on the purchasing power of gold in 1933? This was the beginnings of the Keynesian devaluationist ideology, which wanted to discredit gold as a basis of monetary systems, and install their various currency manipulation wizards instead. Thus, they had a motive to make things look as unstable as possible. Even today, you get academic economists who want to take data like this and say: “look, in 1850-1856 ‘prices’ fell by 20%! Oh, the gold standard era was a time of endless chaos and catastrophe! You need us money manipulators to keep everything stable for you.” In other words, they want to compare a 20% drop in agricultural commodity prices to the sort of economic event that might lead to a 20% drop in the CPI today, which would be a major, Great Depression-type event. Most people fall for this baloney because they don’t know any better.

Is there a reason why agricultural commodity prices could drop 20%? Like, maybe, a good harvest? Or, perhaps, France raised a tariff on cotton imports, reducing imports there, and resulting in a glut of cotton in New York. Could that happen? Duh, of course. It happens every day.

The point is, commodity prices are supposed to be unstable. Actually, it is a little amazing that they have been as stable in the long term as they have been. There is no particular reason why corn should be one value and then the same value a hundred years later.

The next thing to talk about is the idea of “purchasing power.” This is related to the concept of monetary value — a change in monetary value can indeed affect “purchasing power” — but it is NOT NOT NOT the same. For example, a house in my town in upstate New York costs about 10% of the cost of a similar house in Westchester County, New York, which is a wealthy suburb of New York City. If you drive for three hours, the “purchasing power” of your dollar increases by a factor of ten, in relation to houses. Of course, the value of the dollar is the same. So, we need to get away from this concept of “purchasing power.”

What do I conclude from this information? I conclude that this looks about what it should look like if gold were, indeed stable in value. You would expect to see commodity prices go up and down. However, over the long term, there is no tendency for commodity prices to rise or fall on a permanent basis (except in recent decades, which is related to the Green Revolution in industrial agriculture), which might indicate instability of the value of gold itself. That’s about all you can say really.

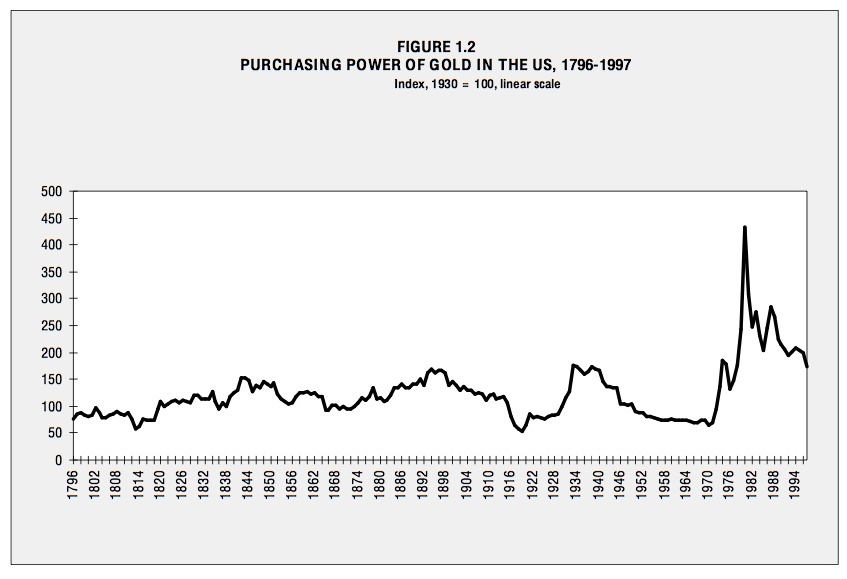

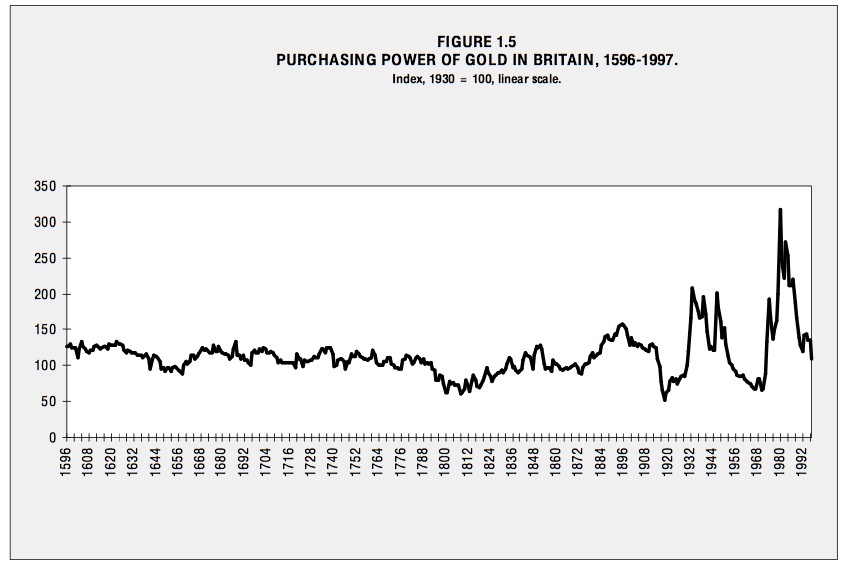

This is the same graph, but rendered in terms of the “purchasing power of gold.” This is really just the Warren and Pearson commodity price index, inverted. The advantage here is that we now have a linear scale, which makes smaller movements a little easier to see.

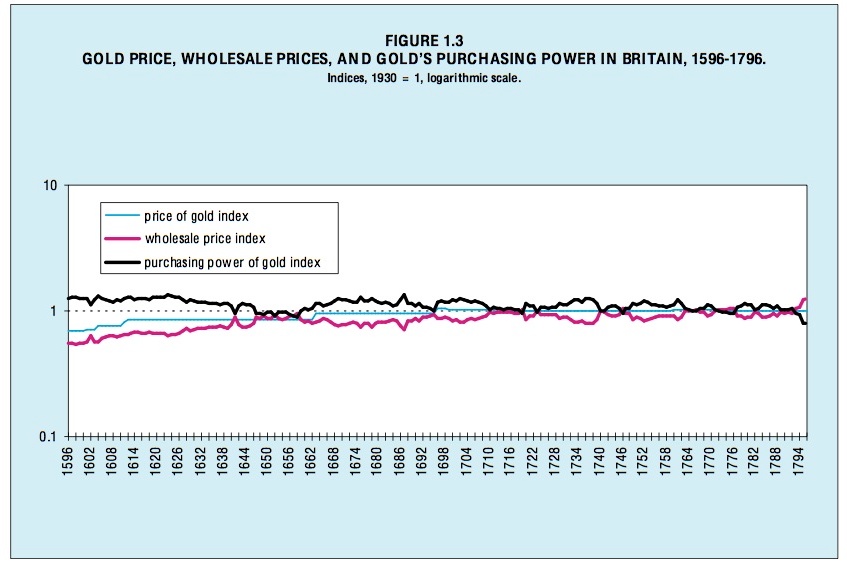

Here is some data for Britain. Looks pretty good. This goes all the way back to 1598.

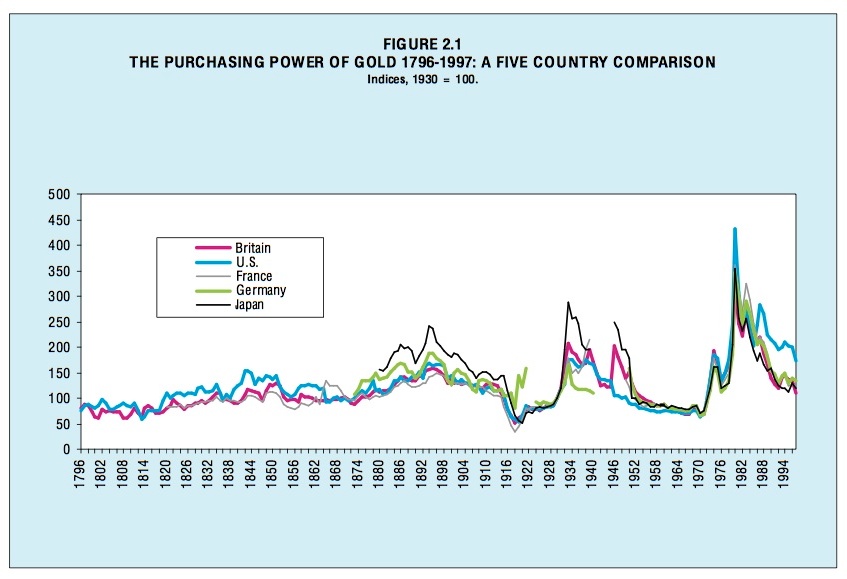

The first thing to notice is that this graph looks different than the one for New York. It is basically the same — a gentle wiggle around the 1 value — but the small ups and downs are different. Is this because gold had a different value in London than in New York? No, I would say that gold was the same value, or there would be arbitrage opportunites. It is very easy to transport meaningful quantities of gold (as opposed to wheat), which is why gold has the same value everywhere, even in pre-industrial times.

This serves as a further caution to not take the fluctuations of corn prices in New York City (the largest component of the Warren Pearson Index) to be some meaningful measure of changes in gold’s value. It’s just corn going up and down.

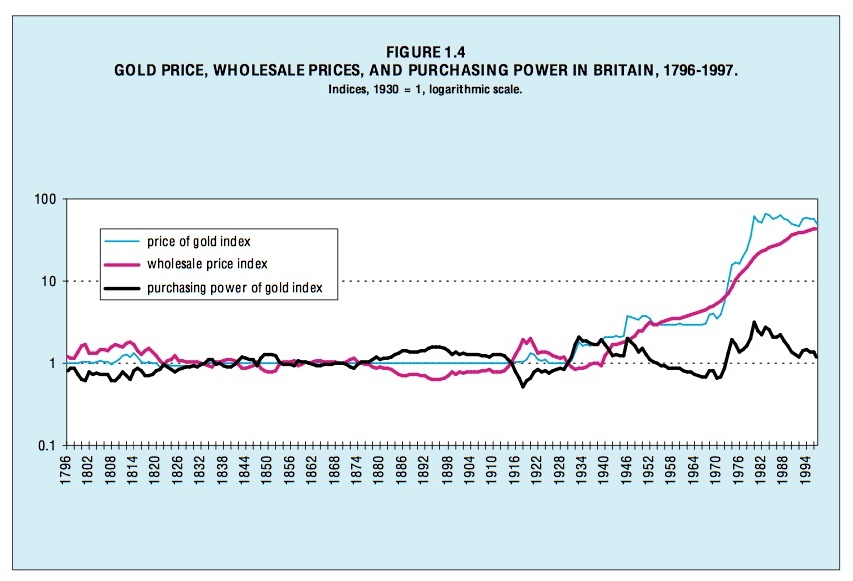

Here we have the two above graphs combined into one magisterial result, which is that gold’s relationship to commodities was basically flat for 400 years in Britain.

Here is basically the same thing, but now for five countries. Once again, you see why I say: don’t make too much of a big deal about some little wiggle or waggle. A wiggle in New York was not mirrored by a wiggle in Japan or Germany. However, gold was the same value in all locations.

I think that is enough for this week. My basic conclusion is that this looks like it should look, if gold were stable in value. So we conclude: yes, gold is stable in value.