Gold Is Stable in Value 3: Production and Supply

May 29, 2011

John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy (1848)

Ibn Khaldun, Al Muquaddimah (circa 1379)

For most commodities, supply and production are almost synonymous. In a given year, the amount available is about equivalent to the amount produced. The difference is accomodated by warehouse inventories of some sort, which are typically a small fraction of the annual production. At the same time, buyers of the commodity typically use it up within a short period of time, for example by literally consuming it in regards to foodstuffs or incorporating it in manufactured products or construction in the case of metals or other commodities. Thus, we can see that these commodities’ price is heavily influenced by supply and demand. If annual production is high or low, then of course supply is high or low, with some variation accomodated by increasing or decreasing warehouse inventories. Demand is rather constant, as the end users have a constant need for the commodity to continue their businesses. Factors such as wars or economic cycles may cause immediate effects on demand; these are not spread out into the out-years.

Let’s take, as an example, copper.

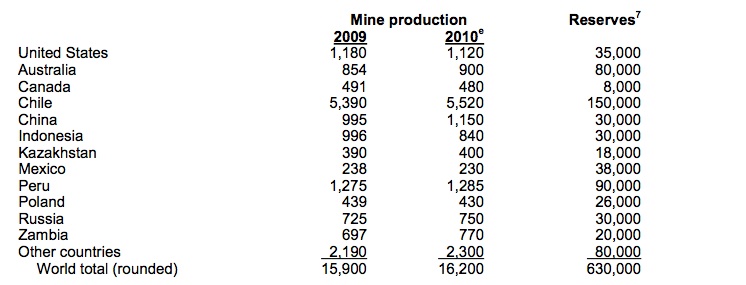

In 2010, the world production of copper was about 16.2 million tons.

http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2011-coppe.pdf

However, known inventories of copper were only about 645,000 tons. This includes major exchanges, not privately held supplies, but I would guess this is most of it.

To state the obvious, 645,000 tons is a lot less than 16,200,000 tons. It is only about 4% of world production. In other words, most of the copper produced in any year goes directly into copper uses, with little ending up in long-term storage.

Production and usage (consumption) are about the same. Often, this copper is not quite “consumed” because it is usually in a condition that allows scrap recovery and recycling. However, it is no longer in some sort of pure bulk format.

http://www.investmenttools.com/futures/

Unlike copper, which is produced continuously, foodstuffs typically have a harvest season. After the harvest, it is necessary to store the product until the next harvest season. So, inventories are higher, in terms of a percentage of annual production. But, they are still not that high.

Here, we can see that grain inventories typically fluctuate around 15% of world production. This is lower than you might think, because some regions have multiple crops and the southern hemisphere is harvesting while the northern hemisphere is planting.

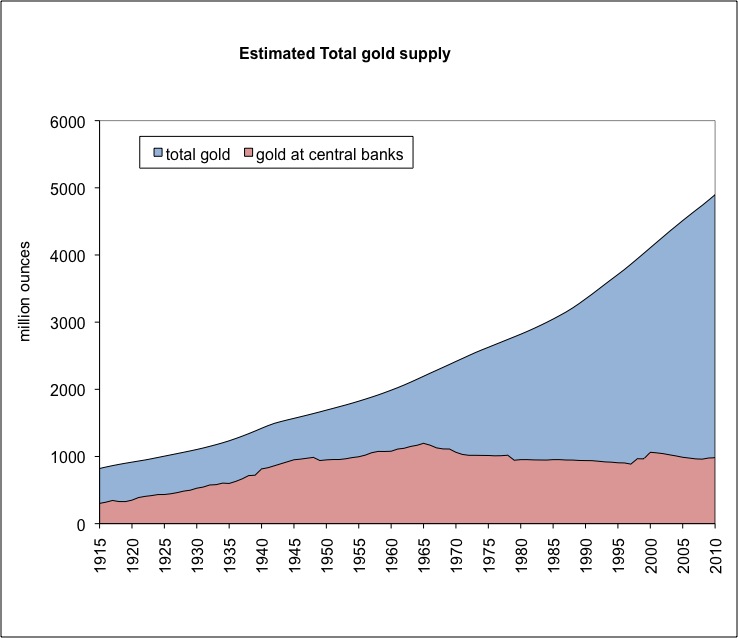

What about gold? The situation with gold is the other way around. Inventories are enormously larger than annual production — about fifty times larger! So, we have copper, in which inventories are 4% of annual supply, and gold in which inventories are around 5,000% of annual supply. Big difference. You can see why certain supply issues that might be a big deal for copper would be totally irrelevant for gold. For example, if world copper production were to fall 20% because of a revolution in Zambia or the Congo, that might drive prices much higher. However, if world gold production were to decline (or increase) by 20%, it would have almost no effect on the availabile “supply” of gold.

Here, we can see that world gold production for 2010 was about 2,250 tons, or about 72 million troy oz. Note that this has been dropping in recent years, oddly enough given the increase in price.

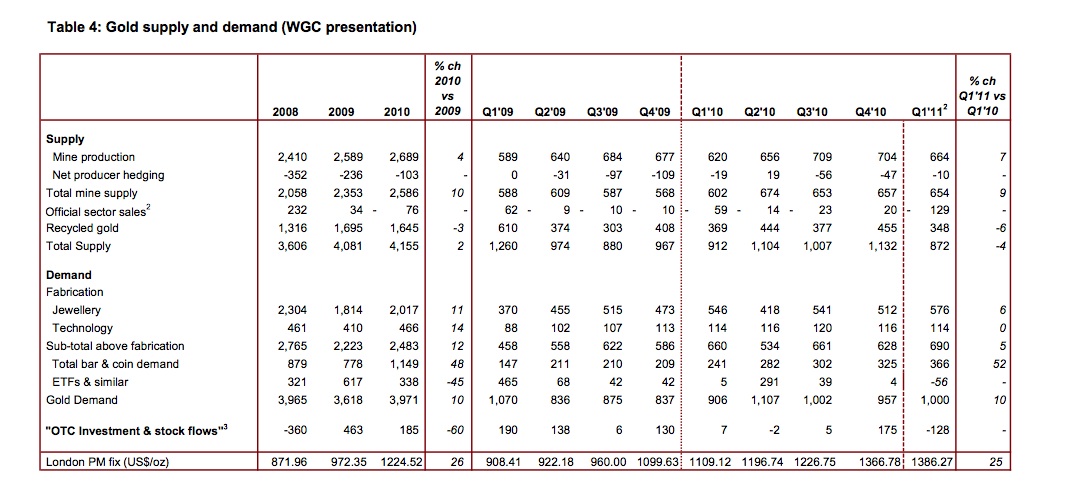

How about “consumption”? Obviously, if 85% of all the gold ever mined is still with us in bullion or jewelry form, then most of the annual production is not consumed, in the sense that copper or corn is consumed, but rather formed into jewellery and bullion products, adding a little bit to that big pile. Here are the stats from the World Gold Council:

We see here that jewellery accounted for 2,017 tons of gold use in 2010. Technology accounted for 466 tons. Coins, bars, ETFs and other forms of bullion were another 2,483 tons. Much of the “supply” was from recycling. This is industrial recycling, and also your “cash for gold” schemes where old jewellery is smelted down to raw bullion.

However, it turns out that jewellery is essentially a “bullion product” itself in most of the world. We are accustomed to having gold jewelry that costs much more than the value of the contained bullion. The gold necklace from Tiffany’s costs $1,000, but has only $150 of gold. The rest is the blue box. However, this is not the case in most of the world, particularly Asia, where most of this jewellery is fabricated and sold. In Asia, the cost of the jewellry is only about 2% higher than the value of the bullion contained. In other words, jewellry is also a “bullion product” not much different than Krugerrand coins, which, by the way, also sell for about a 2% fabrication premuim, just like jewellery in Asia. I would also put things like gold teeth in the jewellery category, as there is no utilitarian reason to make crowns out of gold.

In Asia, jewellery is not used, as it is in the U.S., as primarily a decorative item. It is used as money! One of the largest users of gold jewellery in the world is India. Imagine you are an Indian farmer:

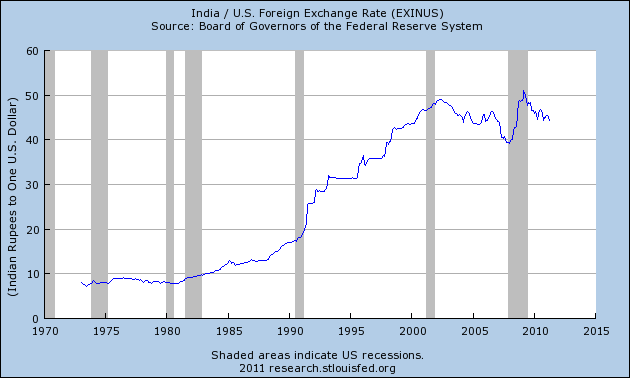

This is a graph of the exchange rate between the Indian rupee and the USD over the past forty years. As you can see, the rupee was a junk currency for many years, steadily sinking in value against the dollar, from 10:1 to 50:1. This followed the 1970s, when of course all currencies declined in value. If you were an Indian farmer, how would you preserve your wealth? In a bank account? There might not even be a bank where you live. In banknotes? I don’t think so. Stocks and bonds? Not an Indian farmer. You can see the very real need for something — anything — to serve as a store of monetary value, and what better than the best of them all, gold bullion. (Note that India’s long period of currency decline ended around 2002, which, not-so-coincidentally, also marks the start of India’s great resurgence from a perennial basket case and charity poster child to emerging market superpower. Can you see why I say that the Magic Formula is Low Taxes and Stable Money?)

So, we see that the true industrial uses of gold are in the technology category. This is gold plating on electronic components, that sort of thing. It is only 466 tons per year, which is only about 17% of annual bullion production. Even this, however, is often not consumed permanently but is retrieved again as scrap recovery, ending up in the “recycled gold” category some years down the road.

In the case of copper, annual “consumption” for industrial purposes is about 100% of supply, which is nearly synonymous with annual production. However, in the case of gold, there is only about 15m oz. of industrial “demand” per year, while available “supply” is 5.0 billion ounces — 333x greater! And, as I mentioned, a lot of that industrial demand is actually satisfied by recycling.

Now you can see why gold is not subject to “supply and demand” issues like all other commodities.