Gold is Stable in Value 4: More Commodities Prices, and Commodity Baskets

June 5, 2011

The effects resulting from a high price of corn when produced by the rise in the value of corn, and when caused by a fall in the value of money, are totally different.

David Ricardo, Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, 1817.

Changes in the purchasing power of money, i.e., in the exchange ratio between money and the vendible goods and commodities, can originate either from the side of money or from the side of the vendible goods and commodities. The change in the data which provokes them can occur either in the demand for and supply of money or in the demand for and supply of the other goods and services.

Ludwig von Mises, Human Action, 1949

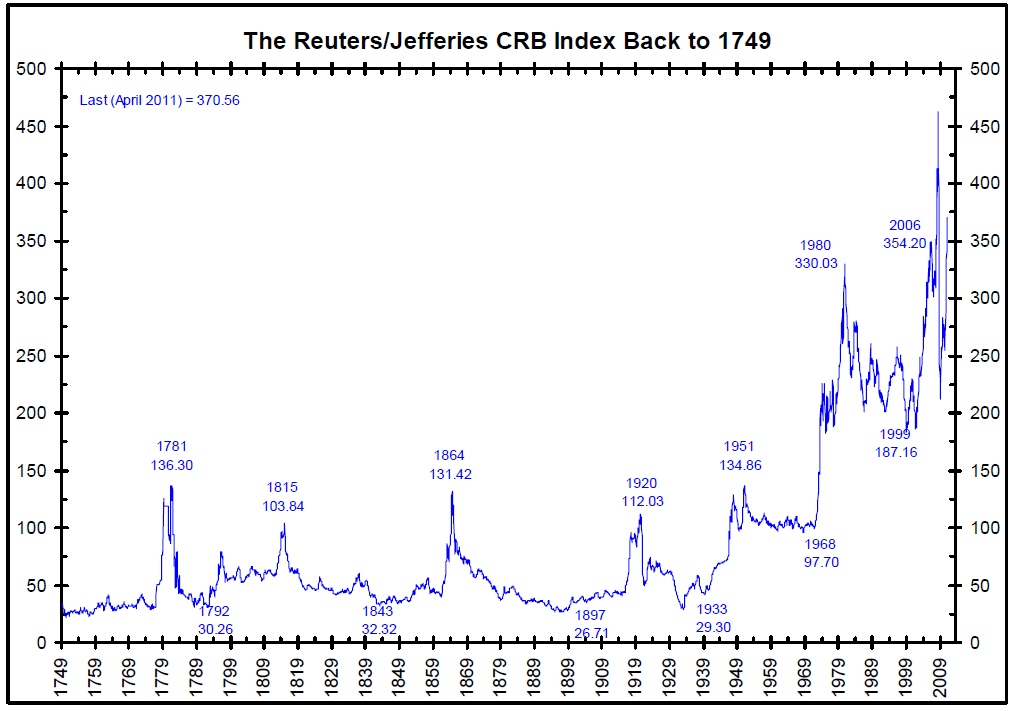

This nice graphic popped up, so I thought I’d talk about it.

This is a commodity basket, represented in dollar terms back to 1749. It probably represents prices in New York City. Prices in London, Vienna or Beijing may have been completely different.

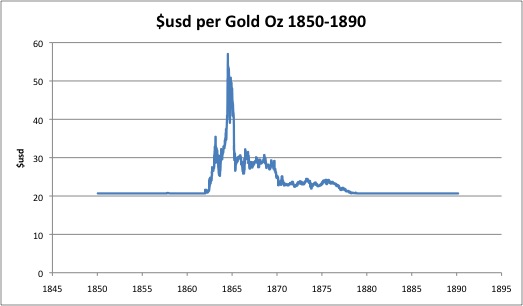

We can see a number of rather dramatic spikes in commodity prices, which correspond mostly to wars, which are also accompanied quite often by currency devaluations. The first peak in 1781 of course coincides with the Revolutionary War in the U.S. Tough to grow food when you are fighting in Washington’s army. The peak in 1815 corresponds to the War of 1812. In 1864 we of course have the Civil War, and also the floating Greenback dollar which was momentarily beyond $50/oz.

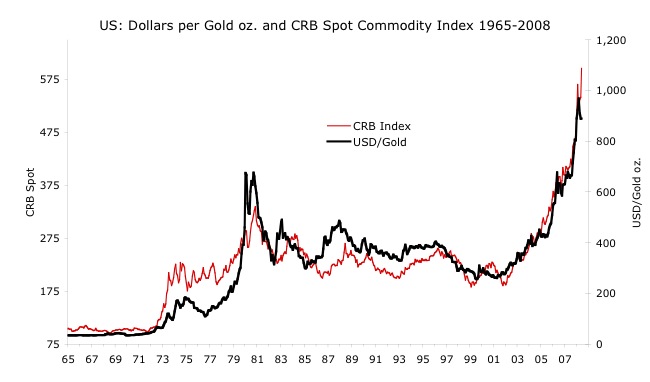

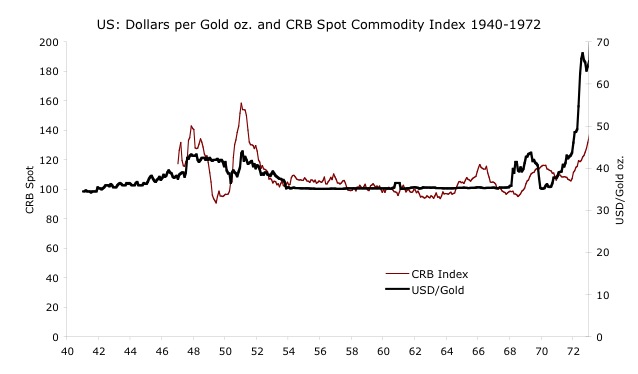

We see a decline in commodity prices in the 1870s, corresponding to the rise of the dollar back to its prewar parity, eventually returning in the 1890s to low points comparable to the 1840s or 1760s. Another spike higher in commodity prices corresponds to World War I, although there was a bit of dollar weakness during that time as well. The dollar was devalued to $35/oz. in 1933, which is why the plateau during the 1950s and 1960s is higher than the previous average level. Then, of course, we have commodity prices rising and falling depending on the value of the dollar from 1970-present.

XXV.6

Among valuable books, which have been forgotten, is to be mentioned that by Joseph Lowe on “The Present State of England in regard to Agriculture, Trade, and Finance,” published in 1822. This book contains one of the ablest treatises on the variation of prices, the state of the currency, the poor-law, population, finance, and other public questions, of the time in which it was published, that I have ever met with. In Chapter IX. Lowe treats, in a very enlightened manner, of the fluctuations in the value of money, and proceeds to propound a scheme, probably invented by him, for giving a steady value to money contracts. He proposes that persons should be appointed to collect authentic information concerning the prices at which the staple articles of household consumption were sold. In regard to corn and sugar authoritative returns were then, and have ever since been, published in the London Gazette, and there seemed to be no difficulty in extending a like system to other articles. Having regard to the comparative quantities of commodities consumed in a household, he would then frame a table of reference, showing in what degree a money contract must be varied so as to make the purchasing power uniform. In principle the scheme seems to be perfectly sound; but Lowe did not attempt to work out the practical details, and his plan involves needless difficulties.

Poulett Scrope’s Tabular Standard of Value.

XXV.7

A very similar scheme was independently proposed, about eleven years later, by Mr. G. Poulett Scrope, the well-known writer on geology and political economy. In a very able but now forgotten pamphlet, called “An Examination of the Bank Charter Question, with an Inquiry into the Nature of a Just Standard of Value” (London, 1833), Mr. Scrope suggests (p. 26) that a standard might be formed by taking an average of the mass of commodities which, even if not employed as the legal standard, might serve to determine and correct the variations of the legal standard. The scheme was also described in Mr. Scrope’s interesting book on the Principles of Political Economy, published in the same year (p. 406), and in the second edition of the same book, called “Political Economy for Plain People,” issued two years ago, (p. 308). The late Mr. G. R,. Porter, without referring to previous writers, gave the same scheme in 1838, in the first edition of his well-known treatise on “The Progress of the Nation,” (Sections III, and IV. p. 235). He added a table showing the average fluctuations of fifty commodities monthly during the years 1833 to 1837.

http://www.econlib.org/library/YPDBooks/Jevons/jvnMME25.html

The idea of a commodity basket is not, actually, the worst idea ever. In principle it is very much like the idea of a gold standard. The goal is the same: a currency of stable value. Unfortunately, Jevons and other proponents typically confuse stable value with stable prices, which are not the same at all. (See my book for a discussion on that topic. I don’t think I’ve ever mentioned it on the website. Can you believe that?) It makes perfect sense that the price of commodities might rise during World War I or the Revolutionary War. What if a currency basket system was used at that time? The value of the currency would have to rise such that the prices would remain stable, or, in other words, a disastrous deflation (currency rise) on top of all the problems of warfare. Hmmm. That’s why gold has always been the monetary standard — it is not subject to these kinds of supply/demand issues, for reasons we began to look at last week.

Gold Is Stable In Value 3: Production and Supply

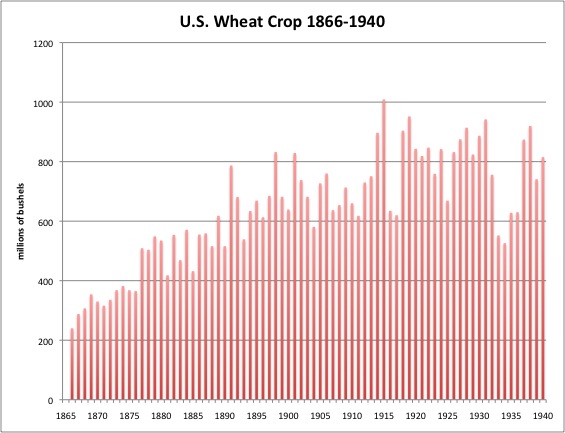

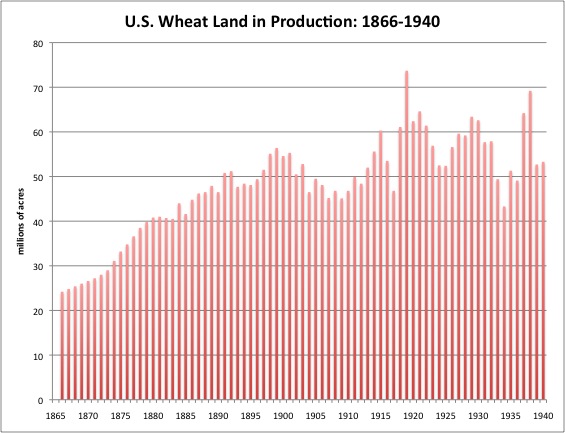

In the 1870s-1890s, another issue was the increasing industrialization of the commodities production process. This was particularly related to the expansion of train systems, which opened up large swathes of land that could be used to produce agricultural commodities for trade. Without a train connection, or some other means of low-cost bulk transport like shipping, agricultural commodities couldn’t be practically exported from their production region. Farming tended to be subsistence-oriented. The increasing supply tended to depress prices, of course until they got to the point at which nobody wanted to open new farmland anymore.

Another issue is: what commodities, and where? Prices in London might vary from prices in New York, although that is not so much of a factor today now that transportation costs have fallen dramatically, which tends to equalize commodity prices globally. What would be the basket weighting? Exactly which commodities? Most commodities come in a variety of grades. There is not only “crude oil,” but Saudi heavy, Tapis light, and so forth. Basis delivery where? The basket weighting would probably change over time. Who would make the decisions on the changes? How?

Some of the support for a commodity basket approach comes from commodity producers themselves, which, in the past, were most of the population, as they were farmers. Normally they wouldn’t complain too much when prices rose, but when they fell — in the 1870s-1890s period for example — they would agitate for some scheme or another to produce higher prices. This typically amounted to one or another argument for a currency devaluation. The farmers often held significant debts, so a devaluation would in effect lighten their debt loads. Maybe you can see why Jevons had a ready audience for his commodity basket ideas, when he was writing in 1875,

Between 1870 and 1890 the number of farms in the United States rose by nearly 80 percent, to 4.5 million, and increased by another 25 percent by the end of the century. Farm property value grew by 75 percent, to $16.5 billion, and by 1900 had increased by another 25 percent. The advancing checkerboard of tilled fields in the nation’s heartland represented a vast indebtedness. Nationwide about 29% of farmers were encumbered by mortgages. One contemporary observer estimated 2.3 million farm mortgages nationwide in 1890 worth over $2.2 billion. But farmers in the plains were much more likely to be in debt. Kansas croplands were mortgaged to 45 percent of their true value, those in South Dakota to 46 percent, in Minnesota to 44, in Montana 41, and in Colorado 34 percent. Debt covered a comparable proportion of all farmlands in those states. Under favorable conditions the millions of dollars of annual charges on farm mortgages could be borne, but a declining economy brought foreclosures and tax sales.

Railroads opened new areas to agriculture, linking these to rapidly changing national and international markets. Mechanization, the development of improved crops, and the introduction of new techniques increased productivity and fueled a rapid expansion of farming operations. The output of staples skyrocketed. Yields of wheat, corn, and cotton doubled between 1870 and 1890 though the nation’s population rose by only two-thirds. Grain and fiber flooded the domestic market. Moreover, competition in world markets was fierce: Egypt and India emerged as rival sources of cotton; other areas poured out a growing stream of cereals. Farmers in the United States read the disappointing results in falling prices. Over 1870-73, corn and wheat averaged $0.463 and $1.174 per bushel and cotton $0.152 per pound; twenty years later they brought but $0.412 and $0.707 a bushel and $0.078 a pound. In 1889 corn fell to ten cents in Kansas, about half the estimated cost of production. Some farmers in need of cash to meet debts tried to increase income by increasing output of crops whose overproduction had already demoralized prices and cut farm receipts.

Railroad construction was an important spur to economic growth. Expansion peaked between 1879 and 1883, when eight thousand miles a year, on average, were built including the Southern Pacific, Northern Pacific and Santa Fe. An even higher peak was reached in the late 1880s, and the roads provided important markets for lumber, coal, iron, steel, and rolling stock.

http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/whitten.panic.1893

By the way, in 1887, a total of 12,894 miles of new railroad track was laid in the United States. This was without petroleum, without electricity, and without all the mechanized tools we have today. The U.S. population in 1890 was 63 million people. Don’t you just love the whiners who say that we can’t build trains today due to declining oil production? What a bunch of bozos.

Then we come to the issue of international exchange. When all countries use gold as their monetary standard, then their foreign exchange rates are fixed. When each country uses its own homegrown commodity basket standard, exchange rates would fluctuate, causing all the usual problems in international trade.

A commodity basket isn’t really deliverable. How would you do it? A barrel of oil, a bushel of wheat, and a pound of copper? Thus, you couldn’t really have a “redeemability” feature when using a commodity basket standard.

Lastly, I will mention that commodity prices tend to lag changes in currency value, sometimes by as much as a year. This was noted by Roy Jastram in his 1977 book The Golden Constant. Jastram says this effect could be seen going back four hundred years. Obviously, you can’t manage a currency system based on an indicator which has a one year lag time. A CPI-type indicator is worse, as the lag here can be up to thirty years!

For these and other reasons, a commodity basket is inferior to gold as a standard of value. But more importantly, gold has never failed. I have never seen anyone say: “we thought gold was a stable measure of value, but we were wrong.” Nobody said: “We used gold as our monetary standard, and it was a mistake.” While probably anyone would admit that gold varies in value by some small amount, it has never reached the extent that it caused a major crisis. Actually, it is hard to even identify a time in which gold varied in value at all. Thus, these “small variations” remain as something of a hypothesis.

Why fix what ain’t broken?