We’ve been talking about Friedrich Hayek’s writings on monetary topics from before World War II.

January 13, 2019: Good Money, Part I: The New World, by Friedrich Hayek

February 10, 2019: Good Money Part I #2: Hayek’s Early Enthusiasms

I’m not sure how much we are accomplishing with this. I feel that perhaps I am not dealing with Hayek’s papers in enough depth to give them fair treatment; and at the same time, giving more detail than almost anyone would care for today. Nevertheless, I think something is accomplished by these attempts to summarize some of Hayek’s thinking of the time. We at least get the general flavor of things.

“The Fate of the Gold Standard” dates from 1932, of course in the midst of the Great Depression and also following soon after the British devaluation of September 1931, which was really shocking. Hayek notes that this devaluation was undertaken in a lighthearted manner that was quite surprising. He explains this development as the spread of two ideas during the 1920s. The first was the idea that the value of gold had become destabilized during and after World War I, supposedly due to titanic gold flows to and from Europe, which, as we saw already, never happened.

November 25, 2018: Net Gold Exports, 1913-1937

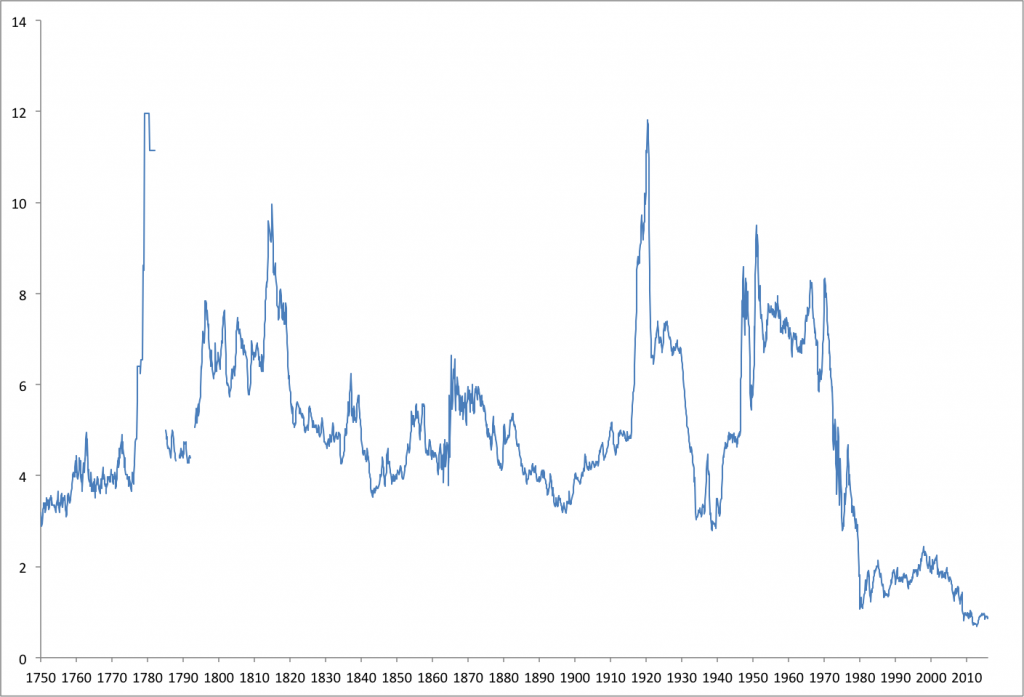

The result of this was the supposedly low value of gold in the 1920s, demonstrated by the relatively high value of commodities vs. gold. I think this was basically just a matter of the supply and demand of commodities.

The rise of the concept of stabilization

What must be remembered first of all is that, as a result of the general paper money inflation in Europe and the associated drift of gold to America after the end of the [First World] War, gold was devalued to such an extent that precisely at the time when the return to the gold standard was the most pressing need in most European countries, in America the fact that even gold did not constitute a completely satisfactory basis for a currency in all circumstances was felt more strongly than ever before. …

The second important factor which determined the development of ideas on monetary policy was that the above-mentioned facts were partly contributory to the extraordinary influence exercised by two particular representatives of the mechanistic Quantity Theory of Money and of the concept of a systematic stabilization of the price level, Irving Fischer and Gustav Cassel. (p. 153-154)

This is an interesting description of the intellectual trends of the time. One of the interesting things about it is that, if gold really did decline in value after WWI because of blah blah blah, then certainly the correct response, according to Irving Fischer, was to raise the gold value of the dollar or other currencies to compensate — for example, a dollar at $15/oz. or British pound at 3 pounds even per oz. of gold. But this was never mentioned. As I’ve said elsewhere, these “stabilization vs. commodity prices” arguments have a one-way-street aspect to them. Everyone wants to “raise the price of gold” (devalue the currency) when commodity prices are going down; and nobody wants to “lower the price of gold” (raise the value of the currency vs. gold) when commodity prices are high. The second strange thing is that people made a big deal about it at all, when commodity prices were actually pretty stable during the 1920s. They were somewhat higher than in 1910 — this was fifteen years earlier — but also, they were so much lower than in 1917 that most commodity producers felt they were shockingly low.

Hayek confirms my version of the failure of the Bank of England in 1931:

From this time on [the failure of Credit Anstalt in July 1931], hardly any serious attempts were made to save the pound, and the Bank of England appeared to have reconciled itself to the fact that convertibility would have to be given up sooner or later. Only this can explain why neither the Bank’s own gold reserves, nor the loans [of bullion] which were gradually being raised in France and America, were utilized to restrict the domestic circulation [reduce the base money supply] by selling these gold assets. What is more, to free the Bank from effecting the reduction in circulation that would otherwise have been necessary, the legal limit for the fiduciary note issue was raised at the end of July, and during July the volume of notes actually in circulation was increased to an extent greater than could be justified by seasonal considerations. … This apparent lack of determination to do something to protect the pound would in itself probably have led to considerable withdrawals of credit [I would panic too, wouldn’t you?]. But when, in September, the well-known additional shocks to confidence increased withdrawals still further, the lack of any struggle as the end came could not have been expected even on the basis of the policy pursued by the Bank of England in previous years. [p. 166]

This is a nice validation of everything that I could read directly from the Bank’s own balance sheet during that time.

May 22, 2016: The Devaluation of the British Pound, September 21, 1931

In general, Hayek’s tone in this paper is somewhat appreciative of the gold standard. He seems to have enjoyed being the daring young reformer, with his various commodity-basket notions, as long as the grown-ups were keeping things in order. But, as a witness to the chaos that ensued after the collapse of the British pound, and many follow-on devaluations worldwide by the end of 1931, he seems to indicate that maybe the old ways were not so bad after all.

However urgent a speedy, general restoration of a free, unmanipulated gold standard must therefore seem from these points of view, the prospects of Britain’s returning in the near future to the gold standard, and of course this would be the prerequisite for a general restoration of the gold standard, are unfortunately, very small. … (p. 167)

However, even if the prospects of Britain’s speedy return to the gold standard are small, nationalism in monetary policy [basically, the idea of domestic macroeconomic manipulation leading to floating exchange rates] has, nevertheless, probably reached or even passed its peak as an intellectual movement … The surrender of the gold standard had brought little change to the industrial situation, in contrast to the high hopes that were entertained for it, and this has had a sobering effect in many ways. [p. 168]

Nevertheless, there is a bit of disingenuousness here. Hayek could have easily argued for Britain to return to the gold standard, at a devalued rate, just as the United States did one year later, devaluing from $20.67 to $35/oz. But, he did not do this. Rather, he takes the opportunity to promote his hobby-horse, “price stability” over currency stability. “In all probability the Bank of England’s policy will aim at stability of the domestic level of prices, and will show little or no consideration for changes in the pound’s rate of exchange.”

“The gold problem” dates from 1937. It is a discussion centering mostly around the large increases in central bank gold reserves of the time, notably in the United States and Britain, which some people thought might be a problem. We looked at this earlier:

June 18, 2017: The gold “sterilization” of 1937

June 25, 2017: The gold “sterilization” of 1937 #2: fumbling and bumbling

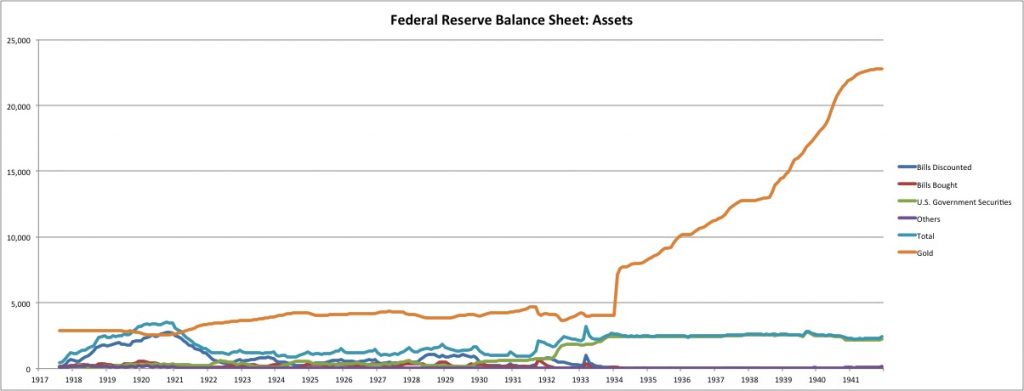

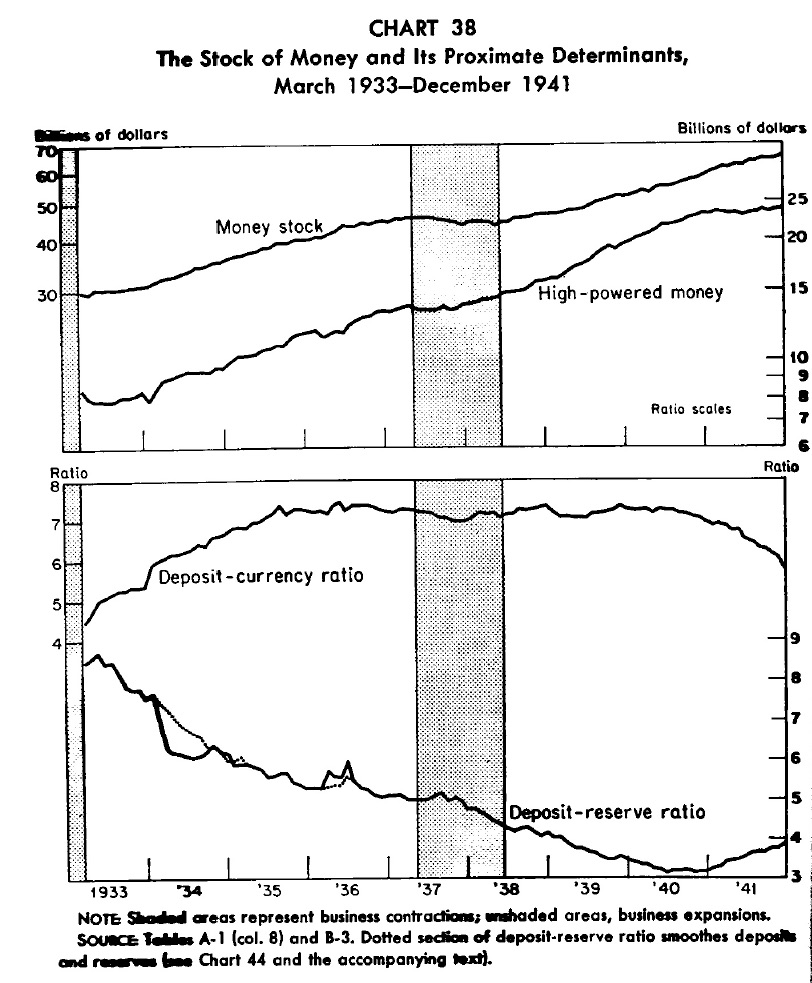

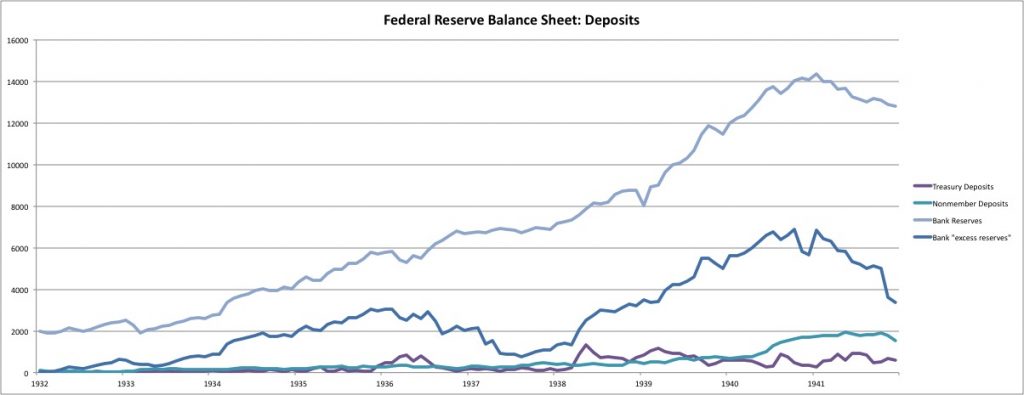

The general impression from this paper is that Hayek was just as confused as everyone else in those days. The gold inflows were simply the product of a higher demand for base money (mostly for bank reserves), combined with a central bank policy of allowing gold convertibility to be the exclusive mechanism for changes in base money. (In other words, there was no increase in debt assets.) This combination required that any increase in bank reserves in particular, or base money in general (currency in circulation also rose slowly) be accomplished via gold inflows. The increase in bank reserves was basically driven by the trend, throughout the 1930s, for banks to hold more and more of their total assets in the form of reserves — essentially, a very conservative stance, growing out of a combination of a desire to have reserves on hand in the event of outflows, and also, a lack of good lending opportunities to which reserves may have been used.

In this chart, gold has a step higher in 1934 due entirely to the devaluation of the dollar from $20.67/oz. to $35/oz. The amount of gold did not increase. You can see how all debt assets flatline after 1934, leaving gold conversion alone as the sole active operating mechanism. By the end of the decade, bullion so overshadowed credit assets that it was nearly a “100% reserve warehouse receipt” system.

This trend towards conservatism (high reserve ratios) was exacerbated by an increase in reserve requirements. Throughout this period, a chronic problem arose due to the fact that, due to the reserve requirements, only reserves in excess of requirements could be actively used as “reserves,” since the required reserves could not be paid out! This is like “requiring” people to keep $100 in their pocket for emergencies, but when an emergency arises, you cannot use the $100 because of the requirement to keep it in your pocket. Banks naturally wished to hold reserves in excess of requirements — $100 to cover the “reserve requirement,” and another $100 that they could actually use in an emergency.

But, you won’t get any of this from Hayek. Instead, he talks a lot about mining production. Again, he sees the gold standard, and gold flows, as a matter of monetary distortions caused by a range of unrelated external factors. Miners dug gold out of the ground, and therefore it ended up on central bank balance sheets, causing an unnatural and unwanted increase in the money supply. Obviously.

Should the production of gold continue to rise–a likely eventuality–a gradual reduction in the convered amount of the circulating central bank money would be the only way to avoid an unwelcome and rapid increase in the money supply. (p. 178)

There are three papers left in this first volume — enough that I think I will leave it for another time.