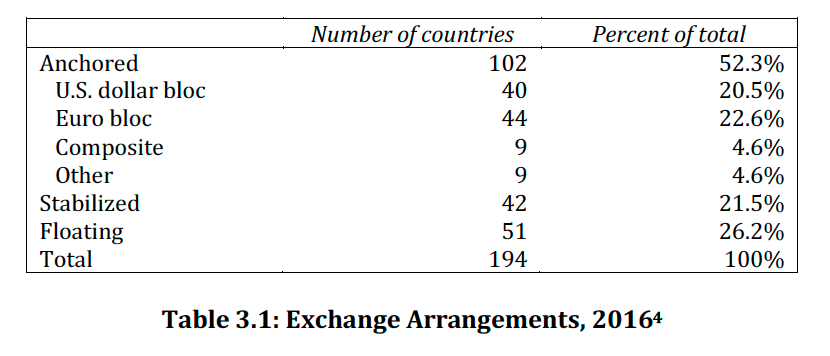

We’re looking at how Russia can, today, go to a gold ruble — to link the ruble’s value to gold. This is not so amazing, really. Today, more than half of all currencies worldwide have an official policy of being linked to the USD, EUR or some other regional currency such as the AUD. Unfortunately, many of these “currency pegs” are not managed very well, and the official policy does not quite match reality. But, at least that is the official policy. Countries that have such a policy should really go to a more formalized currency-board-like system.

How Russia Can Go To A Gold Ruble series

A “gold standard” is the same basic principle, but instead of linking to the USD or EUR, you link to gold. In other words, instead of using the USD or EUR as a “standard of value,” you use gold. This has, you could say, two aspects: First, an official policy or goal. Then, you need some mechanism or technique to actually accomplish the policy or reach the goal, effectively and reliably. You can’t just wish and hope. Not surprisingly, these methods, mechanism and techniques are quite a lot like existing currency boards today.

Today, adopting gold as a standard of value would have some substantial consequences. The most significant consequence would be that the currency’s exchange rate would vary with other currencies, in the same manner that these currencies vary vs. gold. In other words, the RUB/USD or RUB/EUR exchange rate would look like the “price of gold in USD” or the “price of gold in EUR.” This could potentially be very disruptive of trade and investment. However, it is also true that, for a currency to serve as a meaningful alternative to the floating fiat USD or EUR, it also has to vary in value meaningfully from the USD and EUR. I would say that Russia is in a good place today in this regard, because not only have a lot of trade and investment links been cut from the USD and EUR monetary sphere (making exchange rate volatility less relevant), but also, Russia has the ambition to offer a meaningful alternative to US/EU leadership in a wide variety of spheres.

We should also be aware that you don’t have to go “all one or the other.” I have promoted the idea of a “parallel currency,” which means that people would operate in different currencies, as they feel it is appropriate. This is already the common situation in most countries today, where there is a domestic fiat currency, and also a “parallel” alternative, such as the USD and EUR. For example, large Russian companies today might do business domestically in RUB, but they have debt in USD and EUR. Even the Russian government itself, which receives taxes in RUB, has a lot of debt denominated in USD or EUR. It is “doing business in both RUB and EUR.” So, in Russia, you could imagine a situation where people could do business in USD or EUR, as they see fit (this is, or was, already the common state of affairs), and then also have a gold-based alternative, which basically would be the RUB, or even something else. In this case, if the RUB/EUR exchange rate volatility became problematic (with a gold-based RUB), then you could just do business in EUR, in this way obviously sidestepping exchange rate issues altogether. But, increasingly, Russian entities (corporations, the government, individuals) may find it hard to do business in USD or EUR, actually being banned or persecuted by the US and EU itself. For example, they may not be able to open EUR bank accounts, which kind of limits things doesn’t it.

August 23, 2012: My Day In Washington With Ron Paul

Sixty minutes after giving my Testimony in Congress, at the invitation of Ron Paul (who was then the head of the House Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Domestic Monetary Policy) on the topic of “parallel currencies” (thanks Ron!), I was sitting in the Embassy of Russia in Washington DC, chatting with the young economists there. It was fun.

I think I will discuss some of these issues in greater detail later, since that is not the point of today’s item. But, it is good to begin thinking about it.

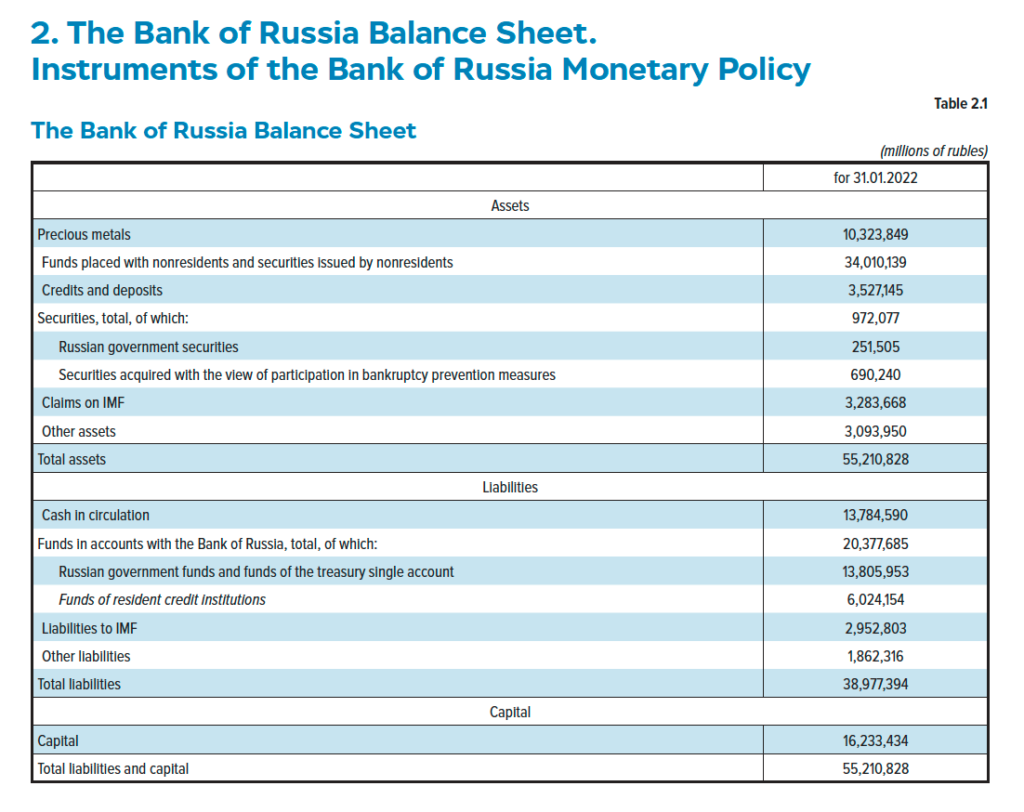

We will look at recent developments in Russia later. Things haven’t changed all that much For now, let’s look at the way things were in January 2022.

This is not much different than the way things were in November, but let’s review.

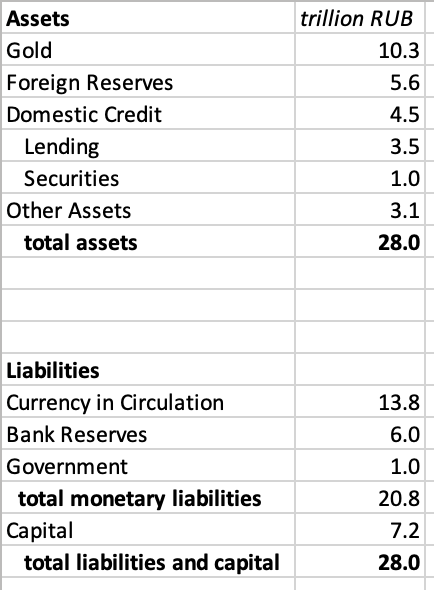

Base Money consists of Cash in Circulation, and Bank Reserves, plus something for the Government’s account. This was 13.8 trillion for cash, and 6.0 trillion for banks. Plus, there’s something for the government, which we will just put at 1.0 trillion for now. The figure on the balance sheet is much higher than this, which represents a sort of government claim on the large foreign exchange reserves, which are now at least temporarily unusable. Thus, the monetary liabilities of the Central Bank are 13.8+6.0+1.0=20.8 trillion.

Against this, we have gold bullion valued at 10.3 trillion, foreign exchange reserves of 34.0 trillion, domestic lending (basically lending to banks) of 3.5 trillion, securities (bonds) of 0.97 trillion including only 0.251 trillion of Russian government bonds, and 3.1 trillion of somewhat mysterious Other Assets.

We estimated that the Foreign Currency Reserves held in Chinese yuan were about 5.6 trillion. The assets and liabilities with the IMF basically cancel out. If we assume that the yuan-based foreign reserves are the only usable reserves for now, the effective balance sheet looks something like this:

Plus, there have been a few developments since January, but not so much.

Now, let’s say that the Central Bank wants to link the ruble to gold at 5000 rubles=1 gram of gold. This seems like a good figure. The Central Bank already publishes RUB/gold rates in grams (rather than troy oz.), and kilobars (1000 gram bars) of gold have become the new standard for large-size gold bars in Asia, particularly China, instead of the 400oz. London Good Delivery bar that was common in the past. The kilobar is really a much nicer item, since it is exactly 1000 grams and doesn’t have an individual bar weight. There could be a 10kg bar in the future perhaps. So, we will use a gram-based standard.

Since there are 31.10348 grams in a troy oz., 5000 rubles/gram is equivalent to 5000×31.10348=155,517 rubles per ounce. This is around where it was in 2020 and 2021. Today, the ruble/gold price is about 6100 rubles/gram, so we would be raising the value of the ruble somewhat against gold. With the dollar recently at $1940/oz. of gold, this would mean 155,517 rubles per oz. / 1940 dollars per oz. or about 80 rubles/USD.

The basic mechanism of controlling a currency’s value is:

When the value is low compared to the standard, REDUCE the amount of currency in existence.

When the value is high compared to the standard, INCREASE the amount of currency in existence.

For my cryptocurrency Stablecoin friends, I showed how this principle is actually how a wide variety of financial assets work.

June 30, 2019: A Rosetta Stone of “Stablethings”

The basic way this is accomplished is by buying and selling assets from the Central Bank’s balance sheet. For example, let’s say that the Central Bank sold 1 trillion rubles’ worth of gold, at 5000 rubles/gram, out of its holdings equivalent to 10.3 trillion rubles. (At 5000 rubles/gram, this is 200 million grams, or 200 metric tons.) The amount of gold on the balance sheet, under Assets, would fall by 1 trillion. The rubles that are received in payment for this gold disappear. Thus, under Liabilities, there would be 1 trillion rubles less of Base Money, in the form of a mix of Bank Reserves and Currency in Circulation.

There is a long discussion about these topics in Gold: The Monetary Polaris.

Thus, we see that by selling gold, the amount of Base Money contracts.

There are actually two important aspects of this operation. First, the supply of Base Money contracts, by 1 trillion rubles. Second, we establish a market price for the ruble, at 5000/gram. Thus, we achieve our goal of managing the value of the ruble at the official gold parity. If you just reduced supply, by 1 trillion rubles, by selling an asset like a nice chunk of Moscow real estate today categorized as “Other Assets,” the Base Money supply would contract by 1 trillion, but the market value of the ruble would still float. Probably, the ruble’s value would rise, since we are reducing the supply, but that is not guaranteed.

You can say: “Well, that’s nice but people will just keep selling rubles until you run out of gold!” But, that doesn’t happen. Since we are reducing the amount of ruble base money supply, at some point, you can’t “sell rubles and buy gold” because the rubles no longer exist. There will be some amount of ruble banknotes, and bank reserves, that people want to keep because they are necessary for doing business. And, if it becomes clear that the value of the ruble is stable at 5000/gram, then why sell? Demand increases. Even in a very bad crisis situation, you rarely have to reduce the base money supply by more than about 20%, because there is some actual demand for the currency for transactional purposes. And, since the currency has stopped falling in value and is now actually going up, the panic abates.

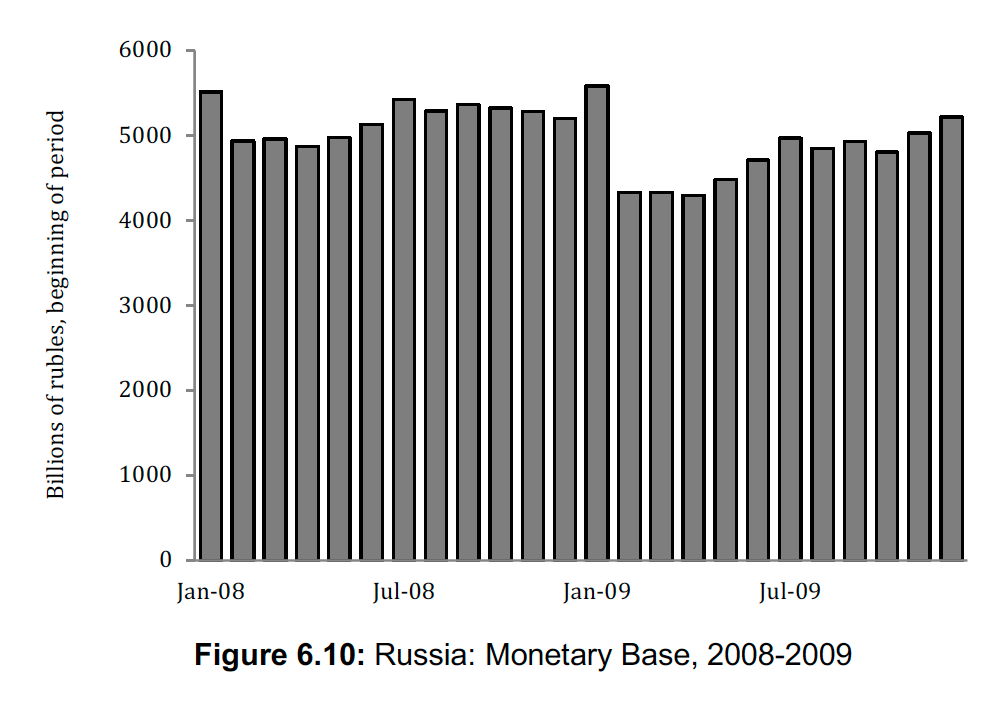

This is exactly what the Central Bank of Russia did in 2008-9, which stopped the weak-ruble panic of that time.

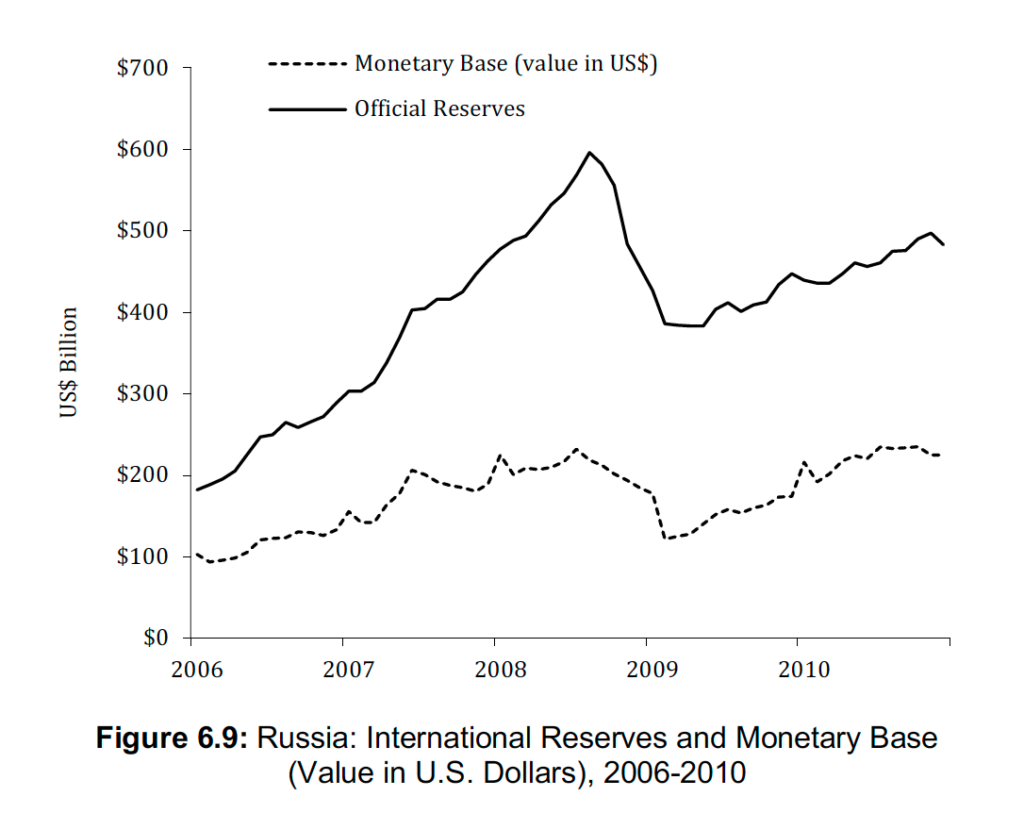

See the drop in Base Money in February 2009? This was about a 20% drop from January, and a 13% drop compared to a year earlier, February 2008 (since there is some seasonality here). Soon afterwards, the Monetary Base began rising again, because actually Russians wanted to hold currency for business purposes, as long as it was reliable.

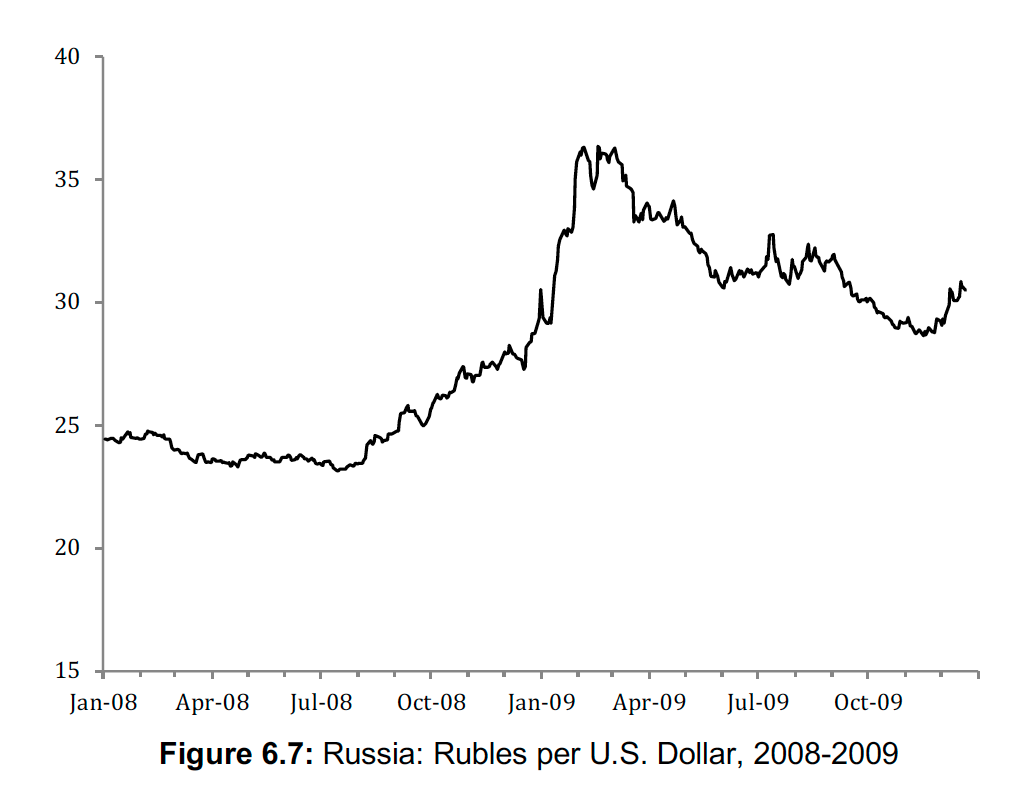

Here is the ruble exchange rate:

The ruble exchange rate blasted higher, just as promised. This was accomplished by selling foreign reserves (USD), so, just as with gold, there were two things accomplished: a reduction in supply, and also, establishing a market value for the RUB. You can see that the RUB/USD rate basically hits a brick wall in February 2009. So, what was happening was: the Central Bank was basically selling USD (taking RUB in payment) at a fixed 36/USD. Then, there was another “brick wall” in March-April around 33/USD, and another, looser plateau around 31/USD in July-September. This “brick wall” is exactly equivalent to selling gold at 5000 rubles/gram. If they wanted to, the Central Bank could imitate this by selling gold at 6000/gram now, 5500/gram a few months from now, and then at 5000/gram a few months after that.

November 24, 2008: Russia’s Currency Crisis

January 16, 2022: What’s Wrong With Turkey #2: Making It Way Too Complicated

However, note that the Monetary Base actually expanded in May-August. It did not contract, it expanded. What appears to be happening was that the Central Bank established a buy/sell at 33/USD, and then 31/USD, but instead of selling rubles and buying USD, people were selling USD and buying RUB. Why were they doing this? First, the ruble was rising, so why not? Second, after selling 20% of all the rubles in existence in February, they didn’t have many rubles left. They wanted more, because they are handy for commerce. And the only way to get them was to sell USD to the central bank.

Here you can see that Foreign Reserves contract, as USD were sold for RUB. But soon afterwards, Foreign Reserves start rising again — even as the ruble was rising. People figured out that they didn’t have enough rubles (having sold them a couple months earlier), so they had to sell USD to buy RUB!

The equivalent today would be: Instead of selling RUB for gold, people would be selling gold back to the central bank for rubles. Gold reserves at the Central Bank would grow.

That might be fun.

Now, there are some other options available today for the Central Bank. Remember, the idea is: Sell Assets to Reduce the Supply of Base Money.

Instead of selling gold, you could sell Chinese yuan. This is exactly what the Central Bank did in 2008, at that time selling USD instead of CNY. But, it is basically the same thing.

You could just sell CNY in the market, at the market price. The Central Bank would receive RUB in payment for CNY, and these RUB would effectively disappear. Base Money would contract.

But, you could also establish a market value for the ruble in this process. For example, let’s say that you wanted to effectively fix the value of the ruble to gold at 5000/gram. You can then just figure out what the equivalent CNY/gold rate is, and sell at that price. For example, the CNY was recently around 6.40 per USD, which translates into $1940*6.40=12,416 CNY/oz. of gold. That works out to about 400 CNY/gram (coincidentally a nice round number), or 5000/400=12.5 rubles per CNY. It would be a “brick wall,” translated into CNY.

This way, you wouldn’t have to sell any gold at all, which I presume is a preferred course of action for the Central Bank today, as it was also for central banks in the past, during the late nineteenth century, which normally used foreign reserves first instead of gold bullion reserves. For one thing, it tends to be a lot easier, since you can just point and click rather than actually shipping bullion here and there.

Since there are 5.6 trillion of CNY foreign reserves, and Base Money of 20.8 trillion, if you sold all the CNY reserves, Base Money would contract by 5.6 trillion or 5.6/20.8=27%. That is a lot. In other words, I think that the ruble’s value could be raised to a 5000/gram parity by selling CNY reserves alone, with some left over. And, as we saw in 2008, after this initial contraction of Base Money, probably of 10-20%, typically we see a rebound afterwards as people realize that things are going to be OK. So, just as in 2008, the Central Bank that offers to buy/sell CNY at 12.5 rubles might soon find that it is buying CNY and selling RUB, and foreign exchange reserves are actually growing, not shrinking. Wouldn’t that be fun.

The last major asset on the Central Bank balance sheet (leaving aside “Other Assets” for now), is domestic debt assets. Basically, this is lending to banks, similar to discount or repo lending at the Federal Reserve. Typically, this asset is not “sold,” but allowed to run off normally. Typically, these are somewhat short-term loans, for example with a two-week to three-month maturity. When the loan comes due, the bank pays it off to the Central Bank. The bank pays this debt using its Bank Reserves at the Central Bank, on the Liabilities side. So, Assets in the form of Bank Lending contracts, and Liabilities in the form of Bank Reserves (Bank Deposits) contracts. In other words, the Supply of Base Money is reduced. However, here we do not establish any market value for the ruble in the process. The supply is reduced, but the ruble’s value is still free to float.

Recently, there was 3.5 trillion of bank lending on the balance sheet. The Central Bank could, for example, let 2 trillion of this run off over the next couple months. Then, this could be combined with around 2 trillion of sales of CNY, out of the 5.6 trillion of CNY reserves. The combination would reduce Base Money by about 4 trillion, or about 20%, from 20.8 trillion recently. The 20% figure is not actually the target here. It is just a rough guideline of what to expect. The target is to get the ruble’s value to rise to 5000/gram of gold. This might take a reduction in the Monetary Base of about 4 trillion, or maybe 3 trillion or 2 trillion, or 5 trillion. Who knows. Just do what you have to do.

As you can see, between the 5.6 trillion of CNY reserves, and another 3.5 trillion of domestic bank lending, we can reduce the Monetary Base by 5.6+3.5=9.1 trillion just using these assets, and doing nothing with gold. That is a lot: 9.1 trillion is 44% of all existing monetary liabilities, the Monetary Base. It is hard to imagine that a contraction of that scale would be necessary just to bump the ruble from around 6000/gram recently to our gold parity target of 5000/gram, the value of a few weeks ago. But, you could do it if necessary, without selling any gold at all. And, the selling of CNY at a price around 12.5 rubles/CNY would imply a ruble/gold price of 5000/gram, which also would achieve our goal of establishing a fixed market value for the ruble at 5000/gram — the gold standard parity.

That is about enough for now. I will add more items with related topics soon — perhaps, given the pace of events, sooner than next week. But, let me leave with a few more points.

First, note that in all this time, I never mentioned interest rates or the “balance of payments.” Just forget about that stuff. It isn’t important. Everything you need to know is up above. (I will explain how interest rates and “the balance of payments” fit into this model later. It can wait because it is not that important.)

Second, note that I am only talking about Central Bank liabilities, not the ruble-denominated liabilities of commercial banks, including deposits, which are most of “M2.” The Central Bank is not responsible for the liabilities of commercial banks. These commercial bank liabilities (deposits) are not actually “money,” but a form of credit. I will talk about what to do when commercial banks get into trouble meeting their liabilities, soon. But, actually, commercial bankers already know all this stuff, so just ask them. But, be warned that certain economic nincompoops will start to make things confusing by claiming that the “money supply” is “M2,” or some other figure. Ignore these buffoons. Just look at the Central Bank’s balance sheet. It tells you what you need to know.

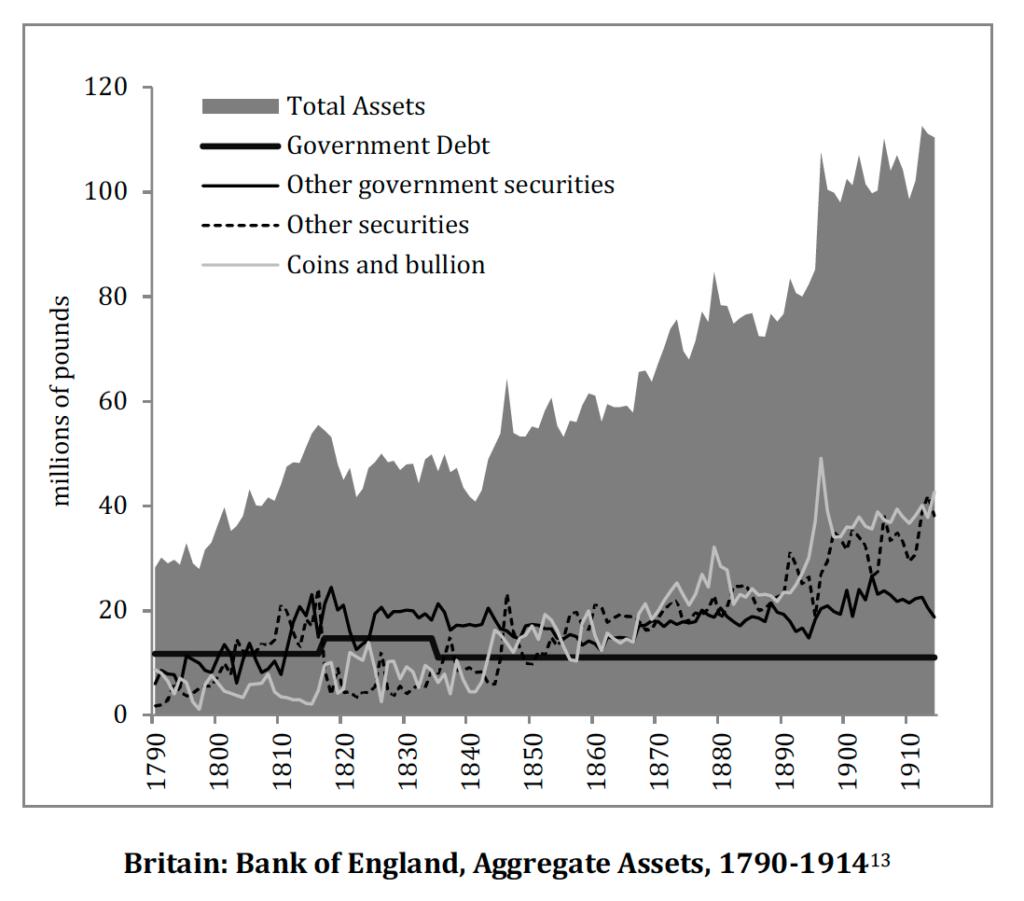

Third, let’s take a quick look at the Bank of England’s balance sheet in the late nineteenth century. It was the premier gold standard currency and central bank at the time.

This historical data is from Gold: The Final Standard.

We can see that the Bank of England had “coins and bullion” (gold reserves) of about 40% of Assets. There was Government Debt (basically a direct loan) and “other government securities” (government bonds) of about 30%, and “other securities” of about 30%. “Other securities” were discounted bills and what amounted to lending to banks and maybe even directly to commercial enterprises. It corresponds to bank lending on Russia’s Central Bank balance sheet today. The CBR does not have much Russian government debt. Instead, it has the government debt of China, aka, “foreign reserves.” So, in a way, the current balance sheet of the CBR actually resembles the Bank of England quite a bit, with substantial gold reserves, a lot of domestic bank lending, and government debt in the form of CNY debt instead of RUB debt.

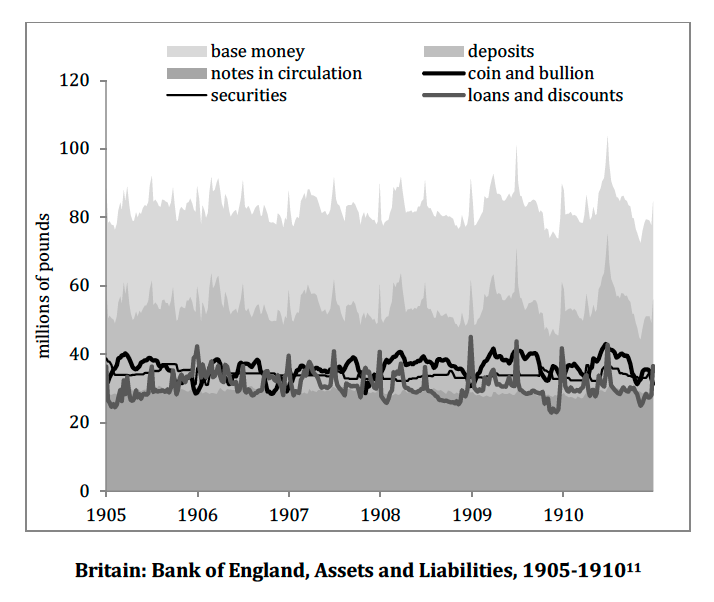

Here are a few years, 1905-1910, which gives an idea of what things looked like at the Bank of England, during the heyday of the Classical Gold Standard era. First, we see that all assets are pretty active. “Securities” (basically, government debt) is somewhat slow-moving but there is some activity. We see that each category (gold, domestic lending, and government debt or “securities”) each account for about a third of Assets. Gold is quite active. This is basically the Bank of England offering to buy/sell gold at the 3L 17s 10d gold parity. Also, lending is quite active.

You have probably heard that when the Bank was suffering gold outflows, the Bank would “raise its Discount Rate,” and that this would “pull gold from the moon.” In other words, there would be gold inflows. People would offer to sell gold to the BOE for British pounds (Base Money). How did this work?

Basically, by raising the rate at which the BOE would lend, it would price itself out of the commercial lending market. Nobody wanted to borrow from the BOE at the higher rates. The existing loan book, which was short-term lending of two weeks to three months, would quickly run down. As banks paid back their loans to the BOE, Base Money would contract. This contraction of Base Money would raise the value of the pound. This would make the Bank of England the highest bidder in the gold market, and thus people would sell gold to the BOE.

This is exactly the process that I described above. We just let the bank lending run off, which would reduce the Monetary Base. You don’t have to fool with interest rates, just stop making loans, and let the existing loans run off. This would tend to support the value of the ruble, until perhaps it reached 4900 rubles/gram in the open market. Thus, the Central Bank, offering to pay 5000 rubles/gram, would be the highest bidder. Gold then “flows into” the Central Bank.

If the Bank of England was too aggressive with its lending, or if there was some decline in the value of the British pound due to any reason, the process would work the other way. The Bank would make loans, increasing the Monetary Base. This might result in a decline in the value of the Pound, thus making it the cheapest seller of gold. People go to the Bank and buy gold. This reduces the Monetary Base, thus cancelling out the excess Lending. The Bank would become aware that its lending was too aggressive, and raise the Discount Rate, thus producing a shrinkage of lending and raising the value of the Pound again. We can see through the weekly activity in both lending and gold that both these processes were very active. The Bank did this because it wanted to earn some interest income from its lending.

Today, if the ruble was at 5100/gram, the Central Bank would be the cheapest seller of gold at 5000/gram. Gold would be sold, and the Monetary Base would contract. The CBR would understand that it should reduce its Lending, perhaps not by “raising the discount rate,” but in any case letting existing loans run off. Also, it might sell some CNY. The value of the ruble would rise, gold outflows would turn to inflows, and perhaps the CBR would buy some CNY also.

So, you can see that the processes which I described above are actually very similar to what the Bank of England actually did, in the Nineteenth Century.