(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on May 22, 2019.)

Whenever the economy gets up a head of steam, as has been the case recently, we have a debate about “does growth cause inflation?” This has been going on a long time — about fifty years, as I count it. You would think that we could have answered that question by now, and not still be talking about it. So, let’s figure it out.

The core of the problem lies in the term “inflation,” which doesn’t have a specific meaning, and which tends to be used rather carelessly by all involved. At times people have attempted to attach a precise definition to the term (I have done this too), but other people don’t follow this protocol, so in the end it remains a muddle.

This is actually a big deal, because, since we don’t want “inflation” presumably, sometimes people do things that will stifle “growth” in an effort to avoid “inflation.” This usually means some kind of “tight” monetary stance, but it can also mean things like tax increases specifically to reduce growth, which probably sounds pretty stupid but it was actually a popular line of argument in the late 1960s and 1970s, among the usual bozos bearing Nobel Prizes.

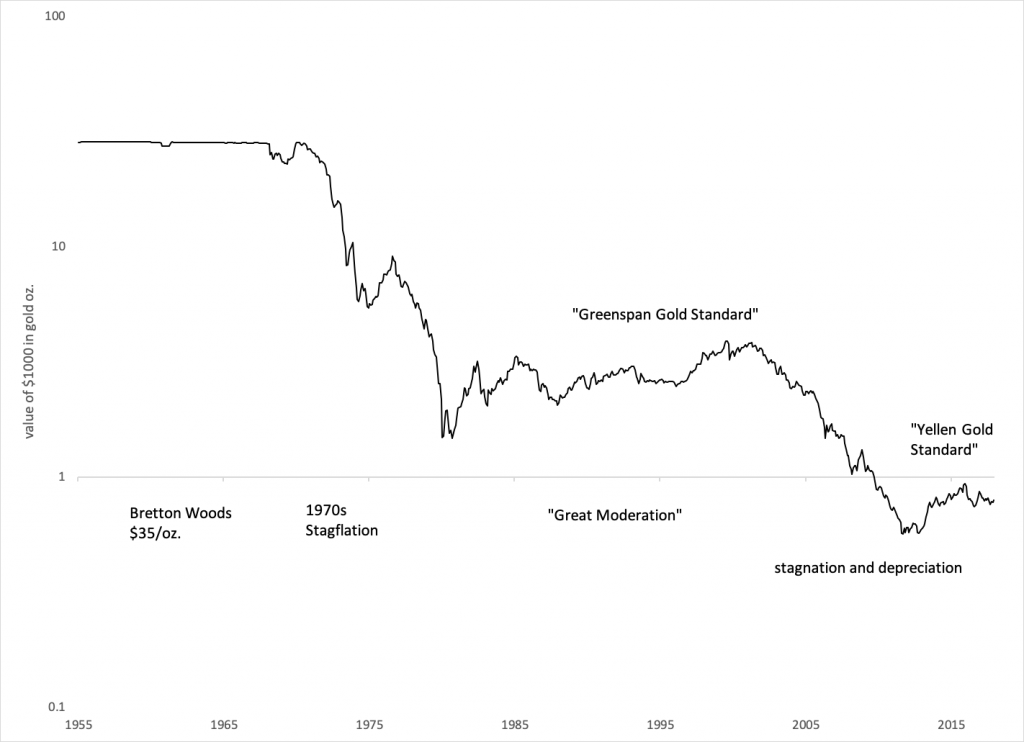

Although the term “inflation” can be misused in many ways, usually it refers to two things. The first is a decline in currency value. For example, the devaluation of the dollar from $20.67/oz. of gold to $35/oz. of gold in 1933 obviously reduced the value of the dollar (and this was reflected in foreign exchange rates as well). In response to this, markets naturally accommodate this new monetary factor, and nominal prices tend to rise over a period of years afterwards. In short, this kind of “inflation” is purely a monetary effect, caused by central bank alteration and mismanagement of the currency.

The term “inflation” can also refer to an increase in some price indicator like the Consumer Price Index. We often say that “the inflation rate is 2%,” referring to a 2% rise in the CPI. This rise in the CPI can come about from monetary causes, as was just described. But, it can also come about just from general economic prosperity, even when there is no monetary cause. In general, rising productivity leads to rising wages; and rising wages are commonly correlated with rising prices for various things, especially services and assets such as property prices. If you go to any city in the U.S. today, you will generally find that if wages are high (as in San Francisco), then the “cost of living” will be high also, in terms of local service prices (dentists, restaurants, daycare) and property prices. If you go somewhere where wages are lower, such as Buffalo, you will find that local service prices and property prices are lower. (Easily traded goods like gasoline or iPads will be about the same in either location.) Obviously this has nothing to do with monetary effects, since the dollar is the same in San Francisco and Buffalo.

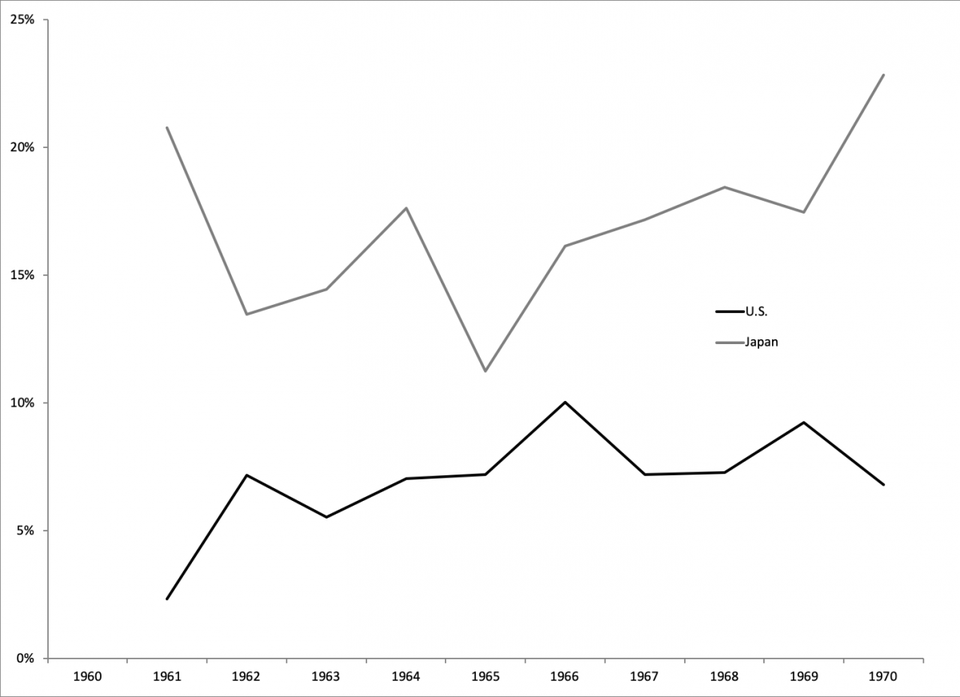

What we find is that countries that are prosperous generally have a CPI (as it is commonly calculated today) that rises perhaps 2%-3% per year, due to these nonmonetary effects. In a high-growth economy like Japan in the 1960s and Hong Kong in the early 1990s, these growth effects can lead to a measured CPI rising in the 5%-8% per year range, without monetary effects. This is “good inflation” as it is a harmless and benign aftereffect of high growth.

If we reword the question “Does growth cause inflation?” to: “Does growth cause a decline in currency value and monetary distortion of the economy?” and also “Does growth cause the measured CPI to rise (in the absence of monetary factors)?” we can clearly see that the answer to the first question is No, and the answer to the second question is Yes. Unfortunately, most economists can only think in one of these two frameworks.

Because economists typically can only think in one of these two frameworks, they tend to assume that the other side is invalid. For example, many people who understand very well that “inflation” can come about due to the effects of monetary distortion following a decline in currency value, tend to assume that the CPI will be more-or-less unchanged in the absence of such factors — in other words, that the CPI growth rate will be very low, perhaps around 0% or 2% (or even negative!) even when growth is high. This is usually wrong.

The other camp tends to assume that increases in the CPI come about via supply/demand factors for goods and services, and assume that there is no monetary distortion as a matter of principle. During the 1970s, the value of the dollar fell by a factor of about ten. During the 1980s, it was worth only about a tenth of its value during the 1960s. This was wholly a monetary effect following the abandonment of the gold standard at $35/oz. in 1971. The price of oil rose by thirteen times, from $3 a barrel to $40, to compensate for the decline in the dollar. But most economists of the time could not understand that this was entirely a monetary effect, and assumed that it had something to do with the supply and demand for oil. Of course they spent the decade spouting the most absurd idiocies.

But the CPI is just one number. It reacts to both monetary effects, and growth effects, and other effects on top of that — even things like changes in sales taxes, regulatory changes, international factors, and so forth. A $15 minimum wage would probably raise prices, but it isn’t monetary, and it is probably not so good for growth either. You can’t tell from the CPI alone whether it is reacting to changes in monetary value, growth, or some other factor. (This is one reason why “CPI targeting” and “price stability” can never be an effective method of central bank currency management.)

If the value of the currency is stable — Stable Money — then you can have outrageous growth rates (Japan’s nominal GDP grew at 16% per year in the 1960s), which would be accompanied by big rises in the CPI of 5%-8% per year, and it won’t be “inflationary.” (This is one — of many — reasons why “nominal GDP targeting” won’t work.) That is, the growth in nominal GDP and the increase in the CPI won’t be from monetary factors. The Japanese yen was linked to gold in the 1960s, and the Hong Kong dollar was linked to the U.S. dollar in the 1990s with a currency board.

The purpose of the gold standard, in the many decades and centuries before 1971, was to produce, as nearly as possible, this Stable Money — money that is stable in value. When you have Stable Money, you can ignore the CPI, as Japan and Hong Kong did, and as the U.S did in those wonderful decades of success before the modern CPI was created in 1940. Wages can rise, and rise and rise and rise, and rise some more. Isn’t that what we want?