We have been talking about NGDP Targeting, a popular idea among somewhat “conservative” economic commentators these days.

September 15, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting

September 22, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting #2: The Classicals and the Mercantilists

I will soon look at some related writings directly, but first I wanted to lay out a bit of a framework. This turned out to be a little bigger project than I imagined.

Let’s consider a “hard” NGDP Targeting system, in which the NGDP target is achieved by direct monetary base adjustment, taking place in basically an automatic fashion according to something like a daily market-generated estimate of NGDP, such as an NGDP futures contract. We will assume, for now, that this system actually works as intended.

Thus, there is no interest rate policy, or foreign exchange rate policy. Since all adjustment of the monetary base takes place in accordance with the NGDP target, it cannot be adjusted in accordance with an interest rate target or a forex target. Interest rates and forex rates are left to the market.

It should be apparent before long that this amounts to manipulating the economy by changing the value of the currency. Obviously, we are “manipulating” the economy, since the economy would not produce unchanging NGDP without this manipulation. This manipulation takes places via a change in the value of the currency, prompted by changes in the monetary base. Basically, the currency goes up or down in value in whatever amount necessary to produce the desired NGDP.

This might be a little bit of a foreign concept, because you are not likely to hear much about this from the NGDP Targeting people themselves. But think of it in comparison with a fixed-value system. We could compare to a gold standard, or even a dollar-based currency board such as used by Hong Kong. Let’s say that Hong Kong adopted an NGDP Targeting system, thus abandoning its dollar currency board. It should be obvious that, if the result was exactly the same in terms of value — in other words, if the HKD maintained its exact dollar parity as it did under the currency board — then the results would be the same too. There would be no functional difference between the two systems. But, since the NGDP Targeting system must do something to achieve its goal of producing unchanging NGDP, it must also produce a different outcome; and the only way to produce this outcome is for the HKD to float compared to the dollar. In general, a lower HKD would produce a higher NGDP, and a higher HKD would produce a lower NGDP, although this relationship is not necessarily linear. There are certain situations where, for example, a higher HKD might produce a higher NGDP; and a lower HKD could produce a lower NGDP; but, it is hard to imagine how this outcome could be achieved by an automatic NGDP Targeting system.

As I have written about elsewhere, I find that the effects of currencies upon economies is expressed largely through their value. This makes sense from a microeconomic perspective. The amount of currency in existence is not very important, for the individual user, if the value is unchanged. However, a change in value, for the individual user, is very important, even if the amount (quantity) is largely unchanged. On a more macro level, monetary price adjustments (“inflation”) take place when there is a change in the value of the currency. The “market” (that is, individual users) accommodate the new value of the currency in price formation, over a period of time. I do not find that there is much change in economic conditions without this change in value. I can imagine situations where there is a change in quantity, without much change in value, and this change in quantity has some effect on overall macroeconomic conditions. This is more plausible in a “currency option three” type situation where there are capital controls and forex controls. But even in these situations, the effect is not very large, unless there is a change in value. The point is: although an NGDP Targeting system is largely expressed as a change in quantity, this change in quantity is not so very important in itself, unless it prompts a change in value. It is the change in value, prompted by the change in quantity, that actually produces the desired effects. The mechanism of the NGDP Targeting system will automatically change the quantity in any amount necessary (increasingly expanding or contracting) to produce the desired outcome of a change in NGDP (or projected NGDP). This is largely equivalent to saying that the NGDP Targeting system will produce the change in value necessary to produce the desired change in NGDP.

So, in imaging what this system really entails, it is useful to imagine how much of a change in currency value would be necessary to produce a stable NGDP, in various scenarios. Often, concepts are best expressed in their extreme forms. For example, the NGDP of Greece fell by about 25% between 2010 and 2015. This was mostly not due to any monetary factors, since the euro was reasonably stable during that time, and other countries using the euro did not have Greece’s problems. Greece’s problems were nonmonetary. We must always remember that, whatever Greece’s nonmonetary problems were — there were a lot of them, and they were severe — none of them would be solved by some kind of monetary manipulation.

Let’s say that Greece instead had an NGDP Targeting policy. How much of a decline in the drachma would have been necessary to turn that 25% decline into something like a 4%-per-year advance? Remember, the 25% decline was not due to monetary factors. It was due to sovereign debt problems, deficits, bank failures, rising taxes, and a lot of other such things. All of those problems would remain. And, on top of that, the value of the currency would fall by a lot. Let’s just put a number on it and say that it would take a 75% decline in currency value, from 1:1 with the euro to 4:1. Now, among other things, the real economy might be even worse off, because people usually don’t like currency collapses so much.

On the other hand, certain debt burdens might be lighter, which might ameliorate a lot of debt, default and bankruptcy issues. As I described in The Magic Formula, this could take basically two forms:

Existing debts would remain denominated in euros. In that case, there would be a colossal wave of defaults, since the value of these debts in terms of devalued drachmas would soar. This is basically what happened to dollar-denominated borrowers in emerging markets in 1982 and 1998.

Existing debts would be denominated in drachmas. In that case, these debt burdens would be lighter. However, there would be huge losses on these debts for foreign investors, and also domestic investors in real terms.

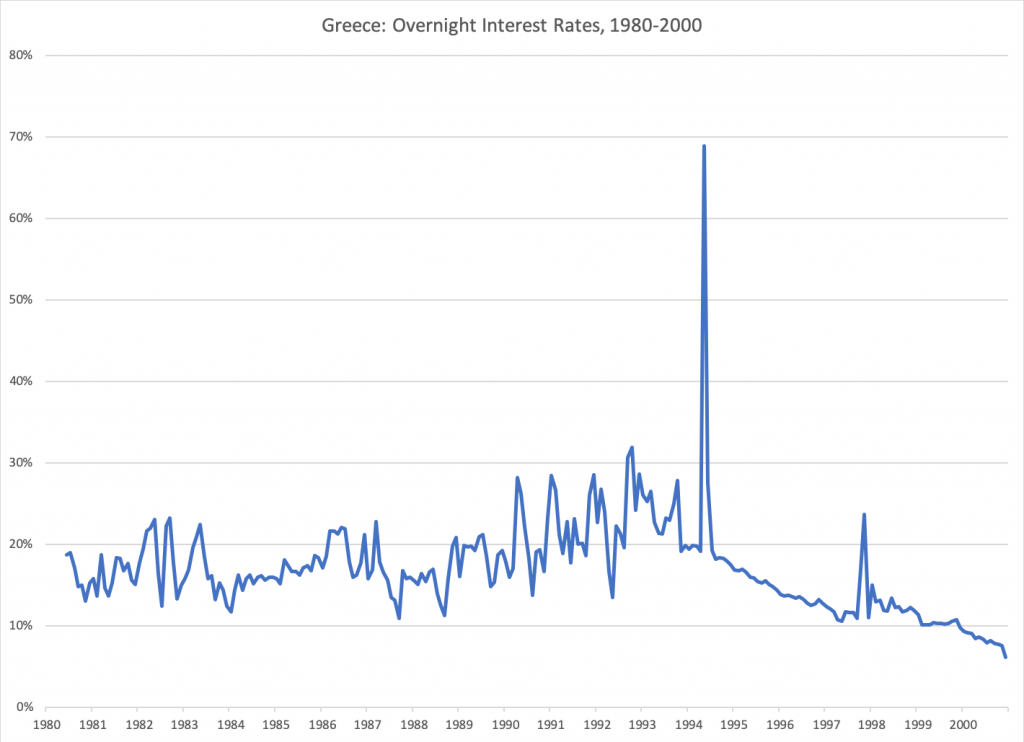

Usually, the NGDP Targeting people are imagining something like the second case. Debts are denominated in local currencies, and so default problems are ameliorated when the currency is devalued. But, let’s say that Greece has had this NGDP Targeting system for some time, and the value of the drachma is going up and down accordingly, and has been doing so for many years. Everybody knows that there is the potential for a big devaluation if the economy turns down, since that is mechanically baked into the cake. Why would you lend in drachmas? Probably, you wouldn’t. That is why Greece, before it became part of the eurozone in 1999 and when it had its own floating currency of not-very-good quality, financed most of its debt in German marks. I believe that about 75% of the government’s total outstanding debt was denominated in German marks.

This is the norm, around the world where currencies are not very good. Governments and local corporations finance in dollars or euros, because nobody wants to lend in terms of Mexican pesos or Peruvian nuevo sol, or Turkish lira or Greek drachmas. Or, if they do, they demand a high interest rate to compensate for the risk of currency loss.

Thus, a policy of NGDP Targeting might lead lenders to lend in terms where they are not going to be obliterated due to currency decline. In that case, the decline in the currency value isn’t going to help very much, because you will end up in the first situation above, where existing debts are denominated in international currencies. This is a disaster, as in 1982 and 1998. Now, why did those disaster happen? Because borrowers were borrowing in dollars. And why were they borrowing in dollars?

If you think through some of these scenarios, it is not too hard to figure out why many countries, including Greece, opted instead for the Classical solution of a “fixed rate” system, in Greece’s case a euro currency union.

But what about the United States? Here, financing in dollars is the norm, so presumably NGDP Targeting would work great because if there was some kind of economic problem, we could just make it all better by blowing up the bondholders through currency devaluation. This was, supposedly, the Lesson of the Great Depression, at least according to Monetarists. But, the reason why financing in local currency was the norm is because of the long history of not blowing up the bondholders — namely, the U.S.’s long history on the gold standard. Today, it is the “strong dollar policy” and the general impression that the USD is a high-quality currency.

But, an official policy of “if things get bad, let’s blow up the currency to hit our NGDP target” might not make lenders very happy about lending in dollars. It definitely won’t after a few experiences with how this system works in real life, producing potentially enormous losses to bondholders. They might demand debts denominated in other currencies, or gold, or perhaps CPI adjustments, or higher interest rates, or some such things. In other words, the same process that would apply to Greece would also apply to the United States, although it would probably be a somewhat slow process, and bondholders would probably have to lose a lot, over and over, before they figured it out.

It works the other way too. If the underlying economic conditions in the U.S. were very good, such that, let’s say, 9% NGDP growth was possible with a stable currency/gold standard (the U.S. hit this level in 1965, with a gold standard), this would have to be jammed down somehow to hit the 4% NGDP Target. Basically, this would take place via a rising currency. Imagine how much of a currency rise it would take to jam down 9% growth to 4%. This is sort of what happened in Japan in 1985-1995, as the yen rose from 220/dollar to 80/dollar, nearly a tripling of value. So, think of the dollar going from $1.20/euro to $0.45/euro (this is a rise in the dollar, not a fall in the euro).

This currency rise would probably be very unpopular. It would be immediately apparent to all that the currency rise is squashing the economy; and that the reason for this is the NGDP Targeting system. Imagine the political pushback that would take place if you were losing 5% per year of NGDP growth to some stupid mechanism that some idiot thought was a good idea, but in practice causes unnecessary problems. In practice, it would not take very long until, just as Paul Volcker ended the “Monetarist experiment” in 1982, the NGDP Targeting program would be trashcanned. (Volcker abandoned the “monetarist experiment” because of a huge rise in the dollar in 1982, which was related to the Reagan tax cuts which allowed more economic growth — which is almost exactly the same as the hypothetical scenario I just described. I am not just making this up.)

NGDP Targeting people don’t like to think about this scenario much. The idea is basically one of recession-avoidance — that is, hitting the NGDP target when, with a different system such as a gold standard, there might be a recession and declining NGDP. This is accomplished basically via a currency devaluation. This is an old Mercantilist idea that took hold duing the Great Depression. The idea of what to do when the real economy is actually better than the NGDP target allows is commonly ignored.

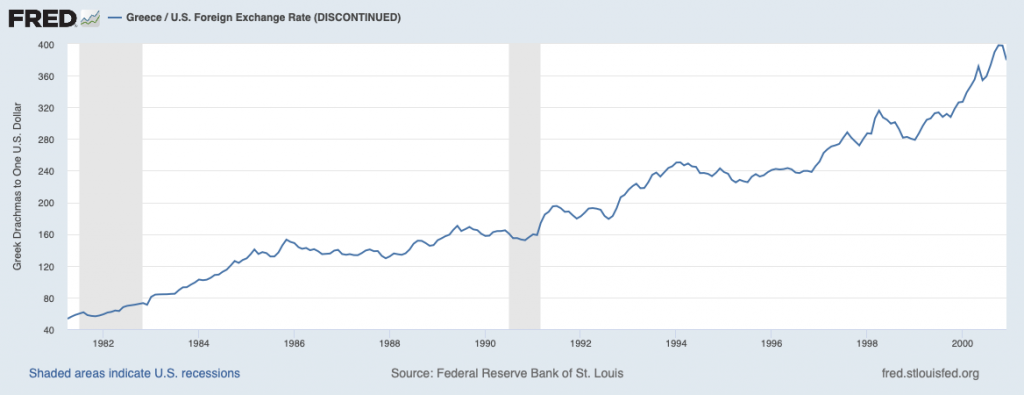

You could argue that an NGDP Targeting system would depress the value of the currency in bad times (recession), to hit the NGDP target, and then raise the value of the currency in good times (recovery, expansion). Perhaps, in the longer run, the currency’s value would be somewhat stable point-to-point, with some ups and downs in between. But, I think that we would find, pretty quickly, that raising the value of the currency back to its pre-decline level would be rather unpleasant and recessionary. In general, I would say that the NGDP Targeting people do not and would not favor this kind of outcome; recreating, for example, the return of the USD to its prewar parity in 1879 or the return of the GBP to its prewar parity in 1925. This could be expressed as a somewhat higher NGDP Target, which has a long-term trend of depreciation, thus avoiding this uncomfortable cyclical rise. Historically, currency devaluation/depreciation has tended to be a one-way street. In other words, the long-term effects of such a policy might look something like the Greek drachma vs. dollar forex rate, a long-term pattern of depreciation.

That is probably enough for now. The point is: I think you can think of NGDP Targeting as, basically, changing the value of the currency to hit the NGDP target. It is usually not described in these terms. But, this is normal among Mercantilists (soft-money advocates) in general. Keynesians talk about interest-rate manipulation and rarely discuss the effects of this upon currency value. 1960s-era Monetarists would talk about M2 (in the Great Depression for example), but again were very quiet about the effects of this on currency value. There has long been a sort of fantasy, or hope, that you could get all the apparent benefits of funny-money manipulation, while also maintaining the Classical advantages of stable currency value. The Bretton Woods System was formally conceived upon this mistaken notion. But this is, as we should know by now, a fantasy.