People may be surprised to find that the Federal Reserve’s target for the “Federal Funds Rate” is a relatively new development. The Fed didn’t start to have an official, publicly announced Fed Funds Target until … 1994. Before then, it targeted interbank lending rates, but in a somewhat informal fashion. During 1979-1982, there was a Monetarist quantity target, and interest rates were largely left to the market. Even the Federal Reserve itself is not quite sure what it was doing. Here is a paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Research Division:

When Did the FOMC Begin Targeting the Federal Funds Rate? What the Verbatim Transcripts Tell Us

“In October 1982 the FOMC deemphasized M1 and moved to what is commonly referred to as a borrowed reserves operating procedure. Sometime thereafter the FOMC switched to a funds rate targeting procedure but never formally announced the change. Given the close correspondence between a borrowed reserves operating procedure and a funds rate targeting procedure, Thornton (1988) suggested that the FOMC went immediately to a funds rate targeting procedure. Others date the switch to the funds rate procedure later. Meulendyke (1998) suggests the switch came in late 1987, while others suggest the change occurred later. This paper reviews the verbatim transcripts of the FOMC meetings to establish the timing of the switch. The verbatim transcripts suggest that the FOMC effectively switched to a funds rate targeting procedure in 1982. The documentary evidence is supported by an analysis of the spread between the funds rate and the funds rate target, which suggests that the differences in the behavior of the spread before October 1979 and after October 1982 are relatively small and economically unimportant.”

Whaaaat?

The interesting thing here, especially, is that the Fed Funds targeting procedure was then abandoned in 2008.

Floored!: How a Misguided Fed Experiment Deepened and Prolonged the Great Recession (2018), by George Selgin

The Federal Reserve then switched to an interest rate paid on reserves of banks at the Fed.

Historically, no interest was paid on reserves. This was a new thing after 2008. The rise in this interest paid on reserves was important in 2016-2020, because, if you were paid 2% to hold cash at the Fed with no risk and perfect liquidity, why would you lend it out at anything less than 2%? But, now this has fallen to 0.10% — almost zero. Maybe, it should just be zero, as it was in the past.

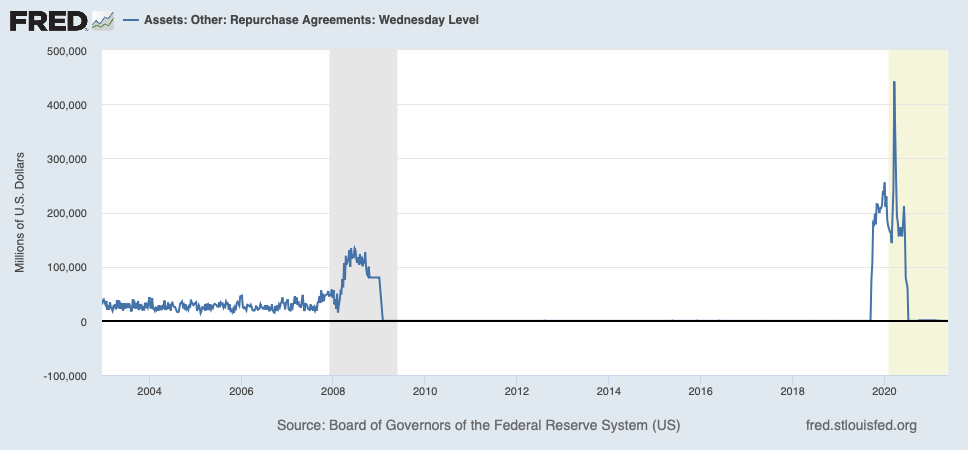

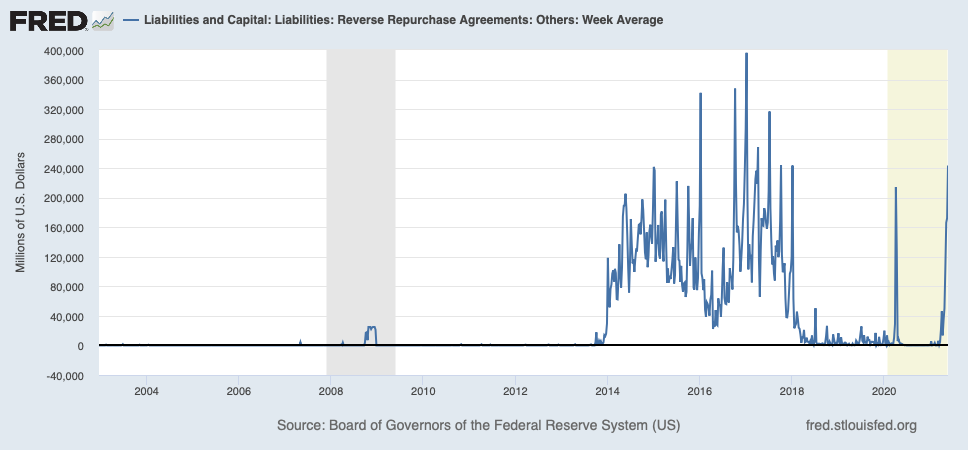

If we are no longer targeting a “Fed funds rate” (interbank lending rate), because banks no longer lend to each other under the new arrangement from Basel III, and we no longer have interest on reserves, and short-term repo lending (and reverse repo) is limited, and the Fed isn’t active in direct lending, then we very nearly have no interest rate policy at all, at least in the traditional sense. (I think the Fed is perhaps more involved in the middle and long end of the curve than it has ever been.) This, I say, is a good thing.