Economists today are very concerned about the “neutral rate of interest.” But, at the same time, they admit that nobody knows what it is.

It would take some time to express where this concept comes from. Maybe we’ll get to that in time. But, let’s start with some basic observations.

Was there ever a time when interest rates were not manipulated by the Federal Reserve, or other central banks in a similar fashion?

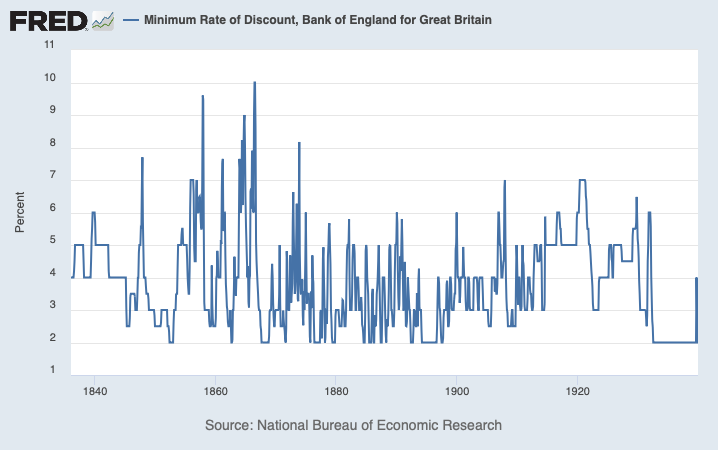

Yes, of course. Although you could argue that interest rates were not quite set by the unmolested market in those days, it certainly was a lot closer than what we have today.

Currencies were, of course, fixed to gold. This also was the primary source of money supply activity, just as I described as common to any Currency Option One system in Gold: The Final Standard.

What we see, in those periods, is a lot of variation in interest rates in the short term, and a lot of stability in the longer term.

There was no “neutral rate of interest” for the short term. It was wildly variable from day to day.

This was a rate for a single institution, the Bank of England, not a market rate. And, it is only monthly; and for loans and discounts typically of about 90 days, not overnight.

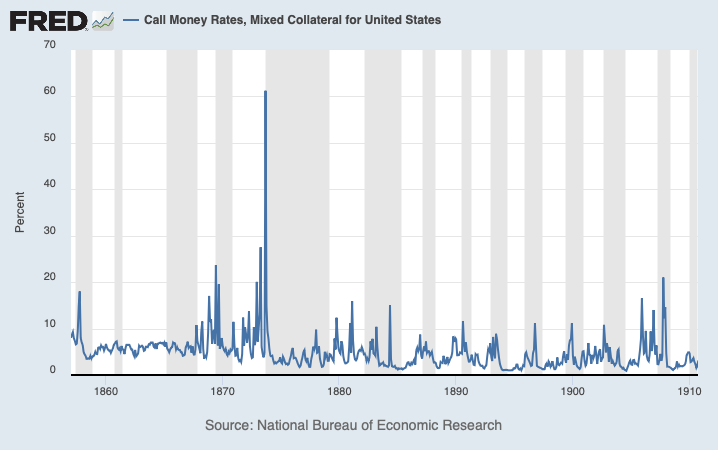

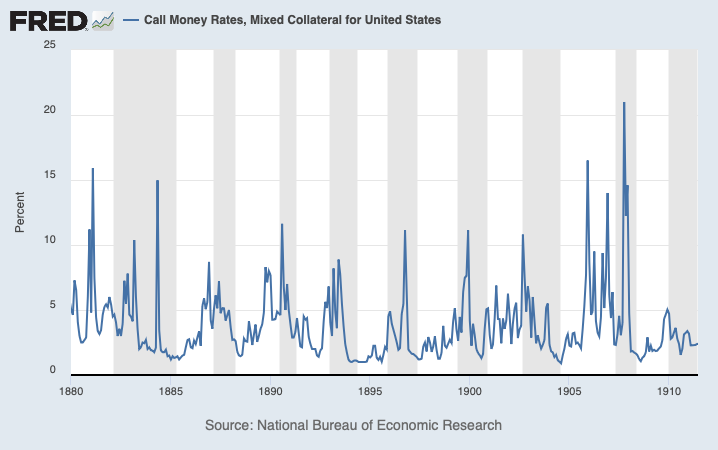

Here are Call Money Rates in the US, before the Federal Reserve, with more of a distributed banking system.

Again, this is monthly data, not daily.

Here is a little closer look at the 1880 to 1910 period, which is a good representation of “normalcy” during that era.

Again, it is all over the place.

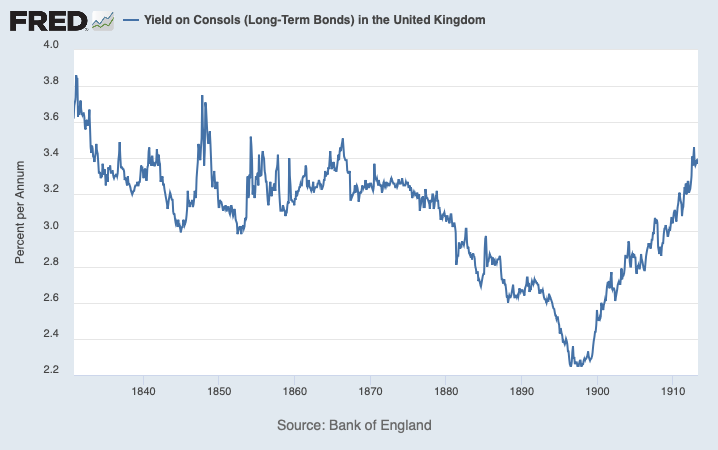

Now remember, long term bond yields were very, very, extremely stable during this time, for good credits and in gold. The exemplar was British government bonds.

This might look like a lot of variability due to the scaling of this graph, but we see about a 100bps move, from 3.2% to 2.2%, between 1875 and 1895. 100bps in twenty years. That is extremely super stable.

The typical experience with “market generated interest rates” within the context of a gold standard system is huge volatility on the short end, and a lot of stability on the longer end.

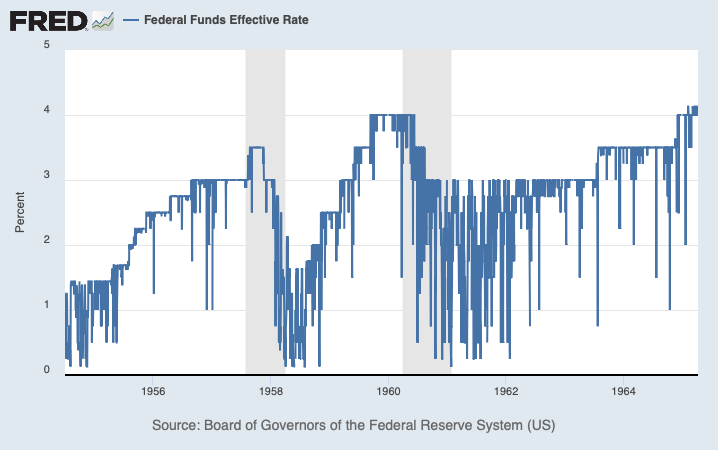

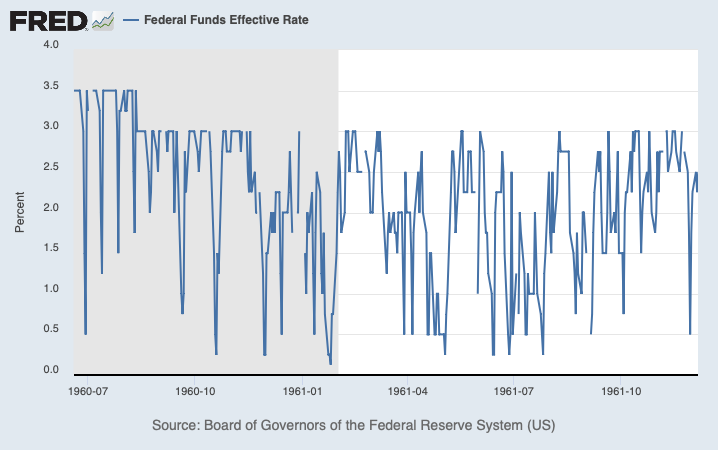

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Federal Reserve had an active Discount Rate policy, where the Fed would lend at a certain ceiling level. But, interest rates were free to vary under this ceiling level, within the context of the Bretton Woods gold standard system and the dollar fix at $35/oz.

The problem here was that the Discount Rate ceiling was generally too low. The Fed tended to continually make Discount loans. Then, these would be replaced, in time, with “long term” purchases of Treasury bonds in the context of some Monetarist-themed policy. Before the 1960s, this excess of Discount Lending was canceled out by gold outflows. The Fed would create money with Discount Lending, and then the gold outflows would remove it. Rinse and repeat. It was a recipe for continuous gold outflows, which we see during that time.

Nevertheless, in this daily data, you can see a lot of variability. Here is a closer look.

It’s all over the place.

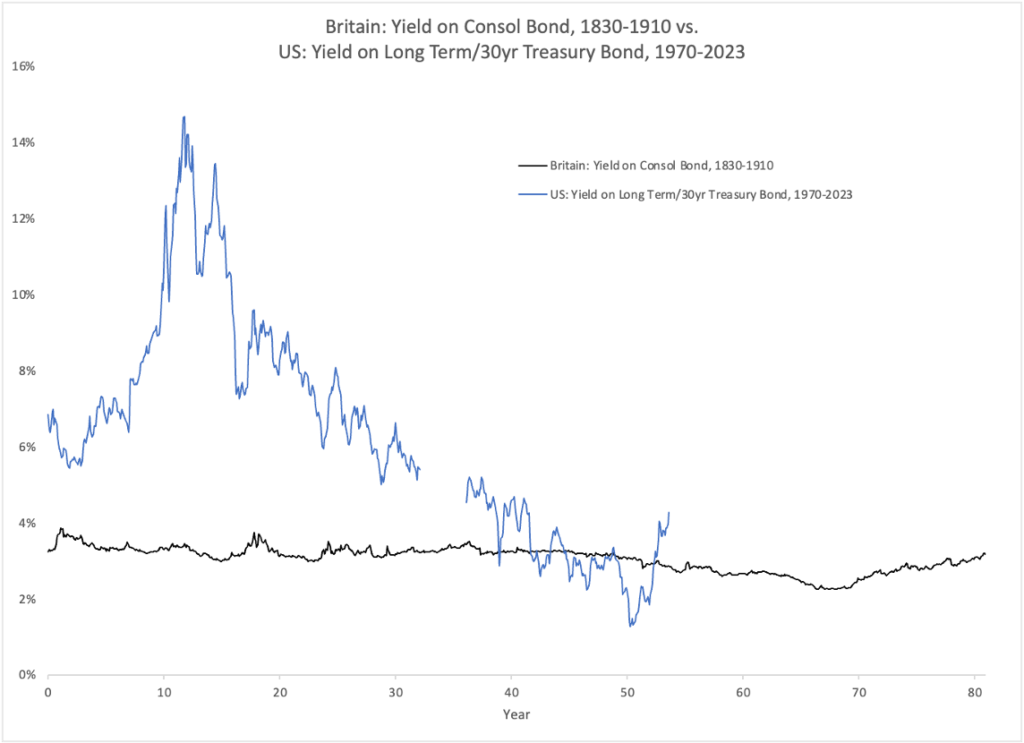

As for an “R-star” for a long-term interest rate, within the context of a Sound Money/Stable Value policy — basically a gold standard system — there is a definite answer. It is about 3.2% for the highest credits, with lesser credits trading at a spread to this. This result actually goes back thousands of years to Holland and even Ancient Rome.

However, for an “R-star” for a short-term Fed Funds rate, or a similar rate target, history shows that nothing along those lines will ever be found.

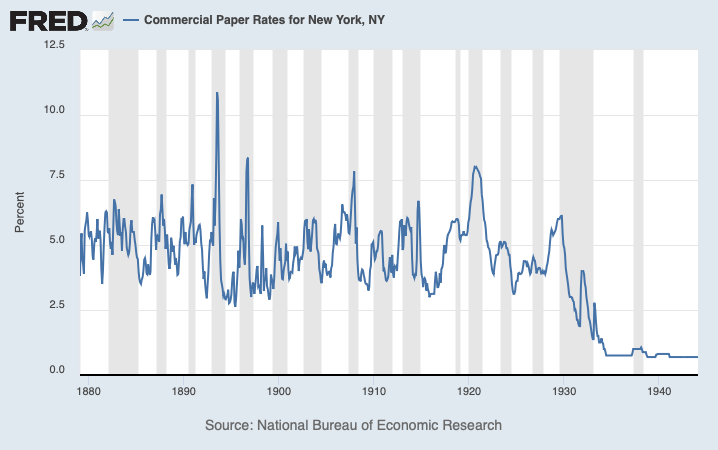

What you can do, however, is look for tendencies with a little longer maturities. Here is Commercial Paper with about a 60-90 day maturity.

Still a lot of variability here, but a tendency around 4.5% or so for investment-grade corporate debt. This collapses during the Great Depression, reflecting the economy and investment opportunities (not good).

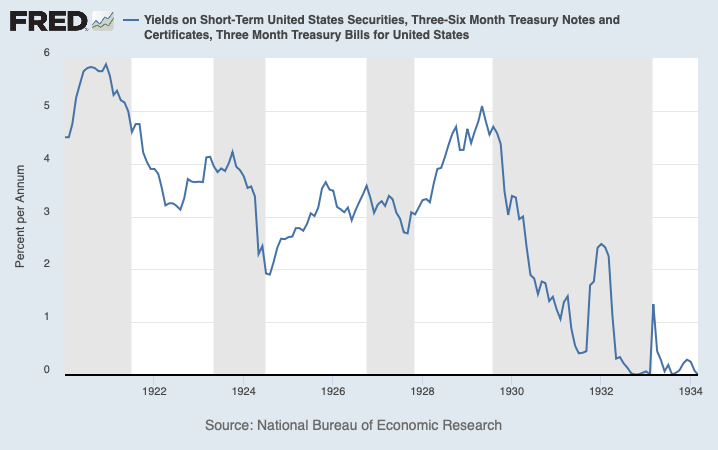

No data on Treasury Bill rates in the 19th century, but here are the 1920s:

Already we are getting quite a bit of manipulative influence from the Federal Reserve, but I think it is nevertheless mostly a “market-generated rate.”

The goal is not a “neutral rate of interest.” The goal is Sound Money. This means: Money that does not change value. In practice, the way this was achieved — very successfully, as you can see in the charts above — is with a reliable gold standard system.

Within this context of “neutral money” (money that does not change value according to the whims and errors of some central bank knuckleheads), interest rates are allowed to form naturally in the context of an unmolested market system.

In practice, there can be some difficulties, which have been called Liquidity Shortage Crises. These were solved either within the context of the Lender of Last Resort function of the Bank of England (a centralized system), or within a distributed system such as Canada had, and which allowed Canada to avoid difficulties such as the problems of 1907 in the US. Both of these systems were entirely compatible with the gold standard policy, and operated successfully for many decades.