I thought I’d continue with “The Rise and Fall of the Gold Standard in the United States,” chapter 7 of Money Free and Unfree, by George Selgin. This exercise is a little overly picky, but it helps bring up some interesting topics. One thing that is nice about commenting on something that I generally agree with, is that I don’t have the problem of disagreeing with so much in a single paragraph that it is hard to even begin.

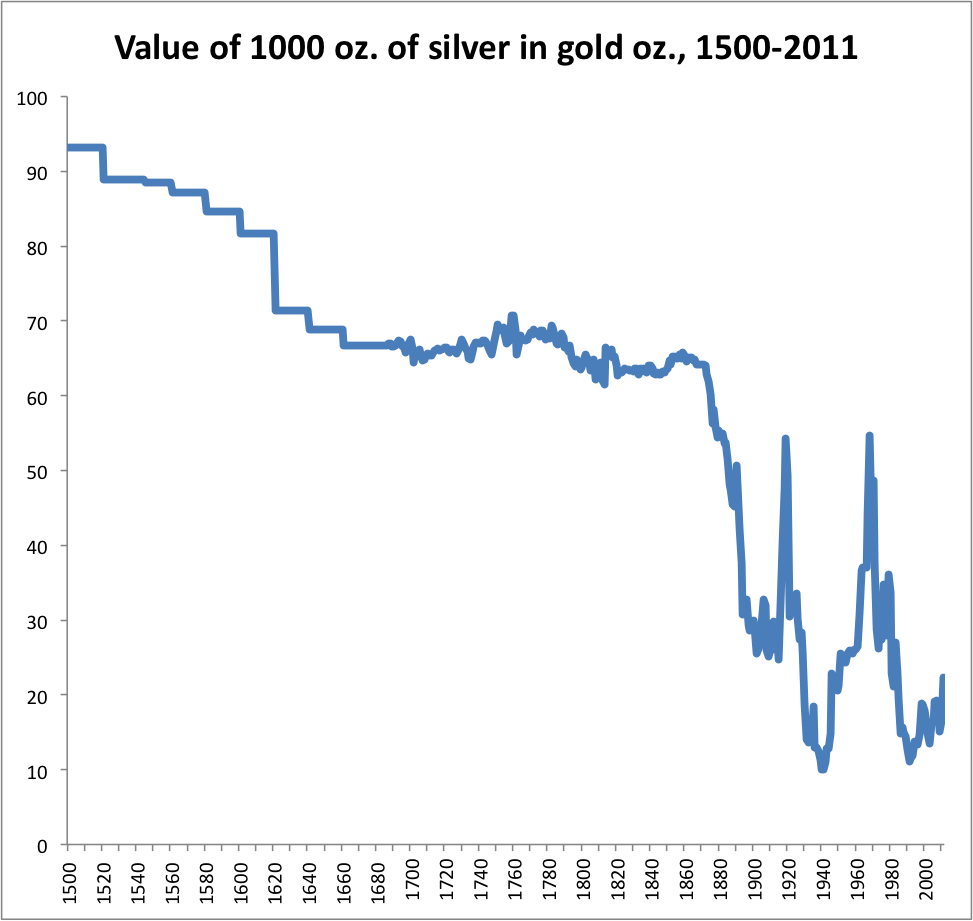

We continue with the section “The Bimetallic Dollar.” This starts a long historical description, which is, overall, pretty good. I have seen far worse descriptions by academics. Nevertheless, since I have my quibble cap on, I will quibble. The section on “Bimetallism Abandoned” (p. 165) seems rather odd to me. Bimetallism, always and everywhere throughout the millennia — Phillip II of Macedon, Alexander the Great’s father, had a bimetallic system in the fourth century B.C. — is based on a condition of relatively stable market value ratios between silver and gold. The basic reason for existence of bimetallism in the U.S. and throughout Europe was that silver and gold traded in a very tight band with each other for centuries. The reason it had to be abandoned, in the mid-1870s, was because this relationship was dramatically violated. It is as simple as that.

Selgin seems to follow Milton Friedman with the idea that the U.S. should have followed William Jennings Bryan and adopted essentially a silver standard after 1896, with the consequent decline in the dollar’s value vs. gold. Some countries in fact did this, notably China and India, and other countries where Spanish/Mexican silver dollars (rather than banknotes) were the common currency, such as Mexico and the Philippines. These countries mostly abandoned their silver standards over time, adopting gold standards instead, and giving Edwin Walter Kemmerer (who set up these new gold standard systems) lots of work to do in the process. In any case, once the threat of devaluation that clouded the 1890-1896 period was past, the economy in the U.S. and Europe did exceedingly well. What’s to complain about that?

Selgin does a nice job regarding the Classical Gold Standard period, which followed the widespread adoption of monometallic gold standards after 1870.

In truth, the world’s most successful international monetary arrangement appears to have worked automatically, with deliberate planning playing an even more minor part in its operation than it had played in its emergence. The institutional setup consisted, first of all, of nothing other than the sum of national gold standard arrangements: there was nothing in it akin to the International Monetary Fund or Special Drawing Rights or other such centralized and bureaucratic facilities. Indeed, as T. E. Gregory (1935: 7-8) observes, “The only intelligible meaning to be assigned to the phrase ‘the international gold standard’ is the simultaneous presence, in a group of countries, of arrangements by which, in each of them, gold is convertible at a fixed rate into the local currency and the local currency into gold, and by which gold movements from any one of these areas to any of the others are freely permitted by all of them.” The most notable achievements of the classical gold standard — including its tendency to keep international exchange rates from fluctuating beyond very narrow bounds and, thereby, encourage the growth of international trade and investment — appear to have required nothing more, in other words, than a resolve on the part of the involved countries to keep their own gold standards in working order. (p. 190-191.)

Bravo! This seems simple enough, but it helps to clear away decades of silly nonsense promoted by various academics posing as experts.

Selgin is a little hesitant to kick the “price-specie flow” nonsense to the curb, as I do, but it is clear that he knows that it smells like baloney:

The mechanism by which the international gold standard automatically regulated national money stocks and price levels was long assumed to be the so-called “price-specie-flow” first explained by David Hume. … In practice, though, the mechanism was seldom triggered under the classical gold standard.

“was long assumed”? In other words, just as Giulio Gallarotti and Filippo Cesarano described so well, it is a bunch of hooey that doesn’t exist in the real world. Once you understand the basic operating mechanisms of a currency-issuing bank, it becomes clear that there is no need to resort to such fantastical explanations.

March 19, 2016: The “Price-Specie Flow Mechanism”

July 18, 2016: The “Price-Specie Flow Mechanism” 2: Let’s Kill It For Good

The section on the 1920s contains the usual admonitions of Great Britain, which raised the floating pound by 10% to return it to its prewar parity in 1925. Even today, people argue that this was supposedly a disaster. I find this talk silly. It was a 10% move. Have none of these economists ever seen a currency, in today’s world of floating fiat currencies, rise by 10%? The Japanese yen went from 260/dollar to 80/dollar between 1985 and 1994. The German mark did similar things. A 10% move in 1925 was a lot like a 10% move today. It wasn’t that big a deal. The U.S. dollar had a similar rise in 1879, when the gold standard was restored at the prewar parity. A great economic boom followed. Britain didn’t have such a boom, but that was largely because of the very high tax rates of the time.

There follows a catalogue of common views of the period 1920-1971, which should illustrate why I thought it was necessary to try to clear out this pile of mishmash, with Gold: the Final Standard. Selgin ends with a bit of discussion about restoring a gold standard system in the U.S.:

The problem here is not that there is no new gold parity such as would allow for a smooth transition, but that the correct parity cannot be determined with any precision and must instead be discovered by trial and error. (p. 209.)

Gimme a break. Many countries have gone on and off gold standards many times throughout history, including Britain and the U.S. It is not really all that hard. Indeed, it seems like we have had a sort of de-facto gold standard in recent years, the “Yellen Gold Standard.” Was that really so difficult?

April 2, 2018: The Yellen Gold Standard

A gold standard that is limited to a single country–even a very large country–cannot be expected to offer the same advantages as a multicountry gold standard or set of gold standards. (p. 209)

This is a concern for small countries. If Singapore were to adopt a gold standard system, it would mean a lot of volatility between the Singapore dollar and other floating fiat currencies — probably an intolerable level of volatility. It is a concern for “large” countries too, like Japan or China. But, it is not so much of an issue for the United States. For one thing, there is already a “dollar bloc” of countries linked to the U.S. dollar, which the IMF informs us contains 44 countries. That’s a start. Big currencies like the euro or British pound are normally kept within a pretty close range with the dollar anyway, and I wouldn’t expect that to change much. Some countries will always be devaluing — the Mexican peso was worth 3/dollar in 1993 and is 20/dollar today–but so what else is now. Exchange-rate volatility with the dollar probably wouldn’t be any worse than it is today, and might be less as more countries join the dollar/gold bloc.

Lastly, we have this:

Finally and perhaps most importantly, it is more doubtful than ever before that any government-sponsored and -administered gold standard would be sufficiently credible to either be spared from or to withstand redemption runs.

This is basically the argument that we couldn’t do it even if we wanted to. There is a lot of anxiety about this, especially after the colossal failure of Bretton Woods in 1971, which everybody wanted to keep, but didn’t know how; and also, the many failures of “pegged” systems (I called them “Currency Option Three” systems in Gold: the Final Standard) over the past fifty years. Unquestionably, we have to make sure that we understand, very well, the proper operating techniques that will allow us to maintain the value of the dollar equivalent to its gold benchmark. If we don’t understand how to do this, then we shouldn’t start. I wrote a whole book about this topic, Gold: the Monetary Polaris. Basically, you use techniques similar to currency boards today, which don’t break, even when they are under substantial speculative pressure; and they are rarely under such pressure, because they don’t break. I think this has been well understood by a few people — Milton Friedman and Robert Mundell, apparently, as I showed in Chapter 1 of Gold: the Final Standard — but alas, seventeen years after that 2001 interview, this is still rare knowledge. So, I would say to those who wring their hands about such things: figure it out.