The Treasury’s Funding Problem

September 7, 2009

It is becoming clearer that the U.S. Treasury has some issues funding its huge debt issuances. The hole is currently being plugged by the Fed’s money-printing operations.

Eric Sprott did a pretty good job of describing the problem:

Sprott Markets At a Glance May/June Special Issue

So, after all this, it should be clear by now as to who is going to cover the difference this

fiscal year. As the lender of last resort, the only purchaser left is the Federal Reserve. In

2008 they were net sellers of almost $300 billion of bonds, but in the first half of this fiscal

year they have been buyers of almost $280 billion of bonds. The Federal Reserve is the

lender of last resort and must support the market for US debt. The policy ‘solution’ that the

Federal Reserve implemented in March 2009 is called ‘Quantitative Easing’. Given our

projections above, this was not an option for them, but a necessity.

Then, there was this intriguing comment from John Mauldin. Using estimates from Hayman Capital, he comes up with about $3 trillion in Federal debt issuance. This is Obama’s $1.85 trillion budget deficit, plus additional off-balance-sheet items. (The accounting for TARP is tricky; the amount that is not expected to be recovered is charged to the deficit. However, it all needs to be paid for upfront, so in terms of debt issuance, TARP is 100% additive.)

Buddy, Can You Spare $5 Trillion?

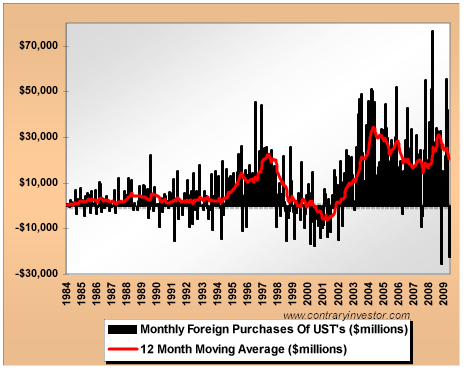

Here’s some info from Contrary Investor about foreign purchases of U.S. assets:

Contrary Investor: Generational Earthquakes

We can see that total net purchases of U.S. Treasury bonds has never been more than about $360 billion per year ($30 billion per month annualized). It doesn’t seem like they are anxious to buy more.

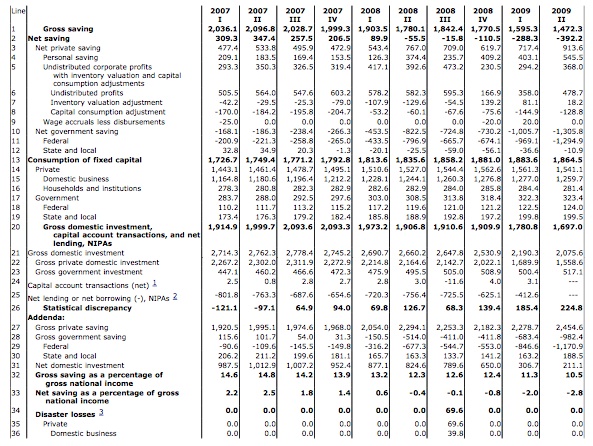

But, the personal savings rate is up, and corporate investment is down. That should free up more cash for buying Treasury bonds, right?

You can get a look at savings and investment here, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis:

Here we see that gross private saving has ballooned to $2,454 billion at an annualized rate in 2Q09. This is up from $2,000 or so before the recession. At the same time, private domestic investment has collapsed to $1,558 billion, from $2,300 billion or so earlier. This has freed up about $2,454B-$1,558B = $900 billion per year of funds that could be used to buy government debt. With $2,000 billion of Treasury bonds to issue, that leaves a $1,100 billion shortfall, which normally would have to be sold to foreigners.

Markets match supply and demand. If this amount was to be sold to foreigners, it might require a higher interest rate. That, in turn, might also incentivize more domestic savings and even less investment, freeing up even more funds to buy Treasury bonds (at the cost of even more domestic contraction). Or, it could incentivize the government to not try to sell so much paper. But, the Fed doesn’t want that to happen, so it is plugging the hole with the printing press.

They have gotten away with this for the time being due to the explosion of demand for base money, in the form of bank reserves held at the Fed. (Categorization of Fed deposits is getting tricky, as they now pay interest. That makes the Fed a lot like a financial intermediary, i.e. a bank, itself.) This is fairly common in times of financial stress. People want to hold assets with a guaranteed counterparty. The Fed seems to fit the bill as they can print money to pay deposits as needed.

This demand for base money may decline at some point. In any case, it might not rise. To the extent that the Fed’s actions are in response to this increase in demand, they are not particularly inflationary. However, it is now becoming clearer that the Fed is also motivated by the Treasury’s funding needs and the desire to maintain low market interest rates. Money-printing in response to budgetary needs is a hallmark of hyperinflationary episodes:

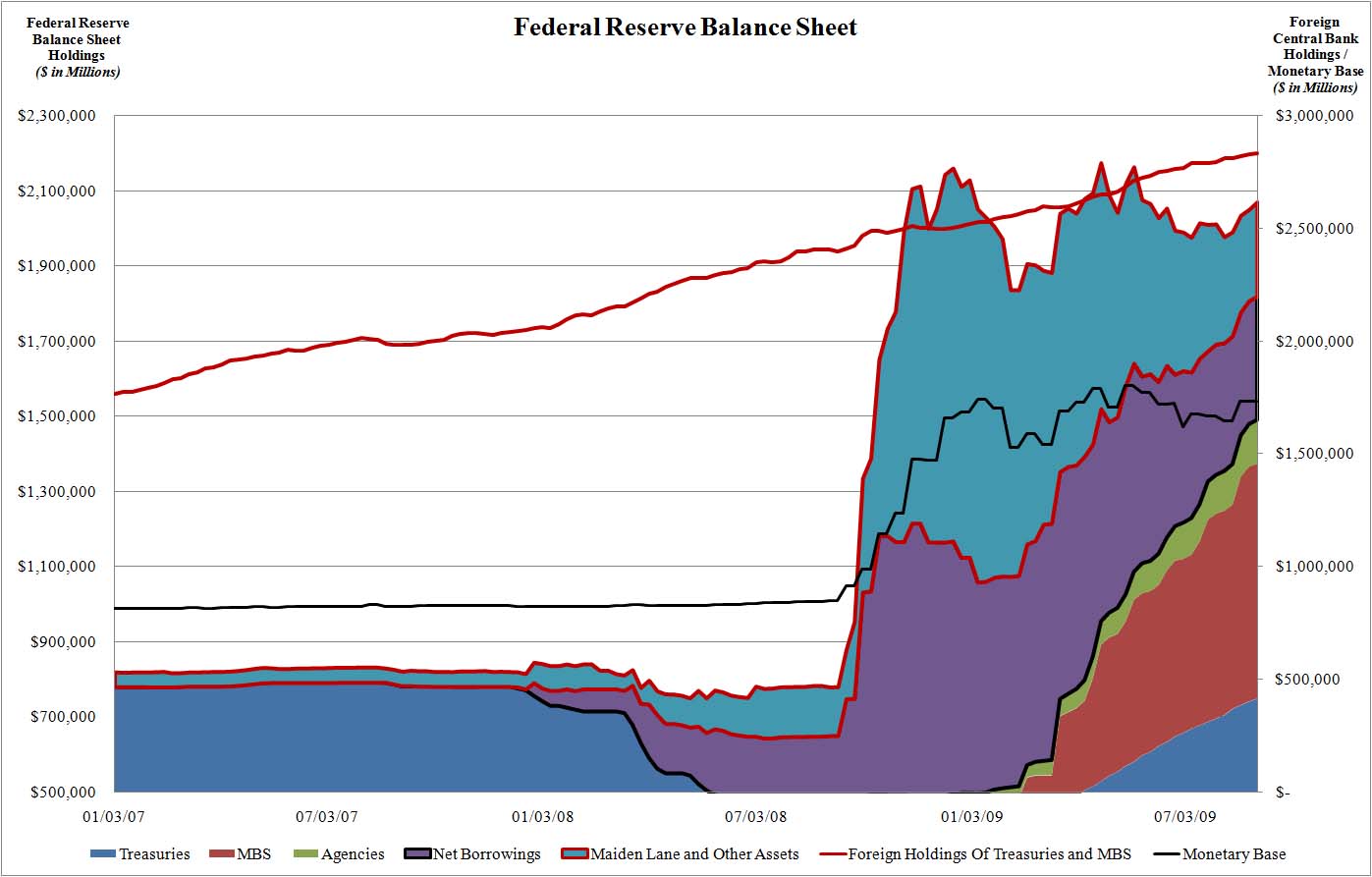

For now, it seems that banks’ desire to hold reserves is roughly steady. The Fed has been replacing loans to institutions with open-market purchases of assets, mainly MBS and agency debt:

Zerohedge: Fed balance sheet update

Thus, in some ways the Treasury has gotten lucky: demand for base money (reserves) has expanded alongside their need to issue bonds.

A couple of things could happen from here: bank reserves could decline, as banks find better uses for their funds than having them sit on the Fed’s balance sheet. That would be normal in an improving economy. Or, bank reserves could hold steady, but the Fed’s need to monetize debt for funding reasons could exceed banks’ desire for reserves. We aren’t too far off that point now, and might reach it by the end of the year. In either case, the Fed would need to stop monetizing debt, and possibly even start selling it. Then, the debt market would begin to equilibrate, matching real demand with real supply. This might involve a rise in interest rates.

It appears this might just be possible if the future deficits are in the range of $1.1 trillion. That could be funded by $900 billion of domestic net savings, plus $200 billion or so of foreign capital. (However, that implies a continuing recession to maintain those very high rates of net savings.) However, that would also eliminate any future big-ticket bailouts. No more TARPs or $850 billion “stimulus” packages. There’s plenty coming up, too, in the form of FDIC, Freddie, Fannie, FHA, etc. etc. bailouts/recaps.

Personally, I think the Fed is under pressure to keep on monetizing the Treasury’s paper. So far, the scheduled purchases of Treasury, agency debt and MBS has been offset by a rolloff of the various direct-lending programs:

$369B of lending remains. So far, the Fed has bought $742B out of a promised $1,450B of agency debt and MBS. That leaves $708B of buying left to do, which is $339B in excess of all direct bank lending. Will they do this?

I’m rather skeptical with respect to central banker “exit” chatter. As markets have recovered and economies stabilized, they have been compelled to articulate somewhat coherent plans for returning to a more stable monetary backdrop. On the one hand, central bankers are keen to reassure the markets that inflation fighting remains a top priority. At the same time, central banks go to great pains to ensure the markets that no meaningful monetary tightening is in the offing anytime soon. On the surface this appears an act of walking a fine line. In reality, markets these days fret only monetary tightening.

In response to Mr. Liesman’s question on the Fed’s commitment to purchase $1.25 TN of agency MBS, Mr. Dudley made telling comments. “Market expectations are very, very important. And the market expects us to complete these programs, to do the full amount. So to contradict that market expectation, I think, is a pretty high hurdle.”

I’ll call that a “yes.” There is also some room in the “Maiden Lane and other assets” category, so we’ll have to see how that works out too.